FAITH & Reason

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Vi on Scripture, Tradition, and Magisterium

ORGAN OF THE ROMAN THEOLOGICAL FORUM NO. 168 JANUARY 2014 PAUL VI ON SCRIPTURE, TRADITION, AND MAGISTERIUM by Brian W. Harrison Part B: Pope Paul’s Personal Magisterial Statements (a) The Continuity of Magisterial Statements on Scripture If we turn now to the addresses of Pope Paul, during and after the Council, which touched on the relationship between Scripture, Tradition and Magisterium, one of the first points which strikes one’s attention is his insistence on continuity between the living Magisterium of the present and the authoritative ‘monuments of tradition’ from the past — both pontifical and patristic. 1. Major Interventions During the Council, at the very time when the second schema on revelation, with its reduced emphasis on Tradition, was being presented to the conciliar Fathers, the Pope made a point of asserting in his first major biblical allocution (25 September 1964) that both Leo XIII’s foundational encyclical of 1893 on biblical studies, and that of Pius XII half a century later, were still both valid and relevant. After commenting that the Church’s criteria for the interpretation of Scripture were well-known to those present, Pope Paul continued: “We shall be content to remind you of how the papal teachings — contained especially in the two great documents ‘Providentissimus Deus’ of Leo XIII and ‘Divino afflante Spiritu’ of Pius XII — are still valid and worthy of the study and adherence of everyone involved in biblical studies.”1 This remark must be seen in the context of influential trends which were giving the impression that Divino afflante Spiritu had virtually superseded all previous magisterial pronouncements on the subject of Sacred Scripture. -

Rhe2009-3-4/Art4-Schelkens/ Eti 856 the Louvain Faculty of Theology 857 the Decades Before Vatican II

Tilburg University The Louvain Faculty of Theology and the Modern(ist) Heritage. Reconciling History and Theology Schelkens, Karim Published in: Revue d’Histoire Ecclésiastique DOI: https://doi.org/10.1484/J.RHE.3.218 Publication date: 2009 Document Version Version created as part of publication process; publisher's layout; not normally made publicly available Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Schelkens, K. (2009). The Louvain Faculty of Theology and the Modern(ist) Heritage. Reconciling History and Theology. Revue d’Histoire Ecclésiastique, 104(3-4), 856-891. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.RHE.3.218 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. sep. 2021 THE LOUVAIN FACULTY OF THEOLOGY AND THE MODERN(IST) HERITAGE RECONCILING HISTORY AND THEOLOGY Introduction In his 1992 studyon the vota prepared bythe Louvain theological facultyin view of the Second Vatican Council, Mathijs Lamberigts has shown that these preconciliar vota deal with a significant variety of themes. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

Fr. Luigi Villa: Probably John XXIII and Paul VI Initiated in the Freemasonry?

PAUL VI… BEATIFIED? By father Doctor LUIGI VILLA PAUL VI… BEATIFIED? By father Doctor LUIGI VILLA (First Edition: February 1998 – in italian) (Second Edition: July 2001 –in italian) EDITRICE CIVILTà Via Galileo Galilei, 121 25123 BRESCIA (ITALY) PREFACE Paul VI was always an enigma to all, as Pope John XXIII did himself observe. But today, after his death, I believe that can no longer be said. In the light, in fact, of his numerous writings and speeches and of his actions, the figure of Paul VI is clear of any ambiguity. Even if corroborating it is not so easy or simple, he having been a very complex figure, both when speaking of his preferences, by way of suggestions and insinuations, and for his abrupt leaps from idea to idea, and when opting for Tradition, but then presently for novelty, and all in language often very inaccurate. It will suffice to read, for example, his Addresses of the General Audiences, to see a Paul VI prey of an irreducible duality of thought, a permanent conflict between his thought and that of the Church, which he was nonetheless to represent. Since his time at Milan, not a few called him already “ ‘the man of the utopias,’ an Archbishop in pursuit of illusions, generous dreams, yes, yet unreal!”… Which brings to mind what Pius X said of the Chiefs of the Sillon1: “… The exaltation of their sentiments, the blind goodness of their hearts, their philosophical mysticisms, mixed … with Illuminism, have carried them toward another Gospel, in which they thought they saw the true Gospel of our Savior…”2. -

Encyclica. Divino Afflante Spiritu A

Cooperatorum Veritatis Societas Excerpta ex Documenta Catholica Omnia 1943-09-30 - SS Pius XII - Encyclica. Divino Afflante Spiritu A. A. S. XXXV (1943), pp. 297-325 PIUS PP. XII LITTERAE ENCYCLICAE DIVINO AFFLANTE SPIRITU AD VENERABILES FRATRES PATRIARCHAS, PRIMATES, ARCHIEPISCOPOS, EPISCOPOS ALIOSQUE LOCORUM ORDINARIOS PACEM ET COMMUNIONEM CUM APOSTOLICA SEDE HABENTES ITEMQUE AD UNIVERSUM CLERUM ET CHRISTIFIDELES CATHOLICI ORBIS: DE SACRORUM BIBLIORUM STUDIIS OPPORTUNE PROVEHENDIS VENERABILES FRATRES, DILECTI FILII SALUTEM ET APOSTOLICAM BENEDICTIONEM Divino afflante Spiritu, illos Sacri Scriptores exararunt libros, quos Deus, pro sua erga hominum genus paterna caritate, dilargiri voluit «ad docendum, ad arguendum, ad corripiendum, ad erudiendum in iustitia, ut perfectus sit homo Dei, ad omne opus bonum instructus»1. Nihil igitur mirum, si Sancta Ecclesia hunc e caelo datum thesaurum, quem doctrinae de fide et moribus pretiosissimum habet fontem divinamque normam, ut ex Apostolorum manibus illibatum accepit, ita omni cum cura custodivit, a quavis falsa et perversa interpretatione defendit, et ad munus supernam impertiendi animis salutem sollicite adhibuit, quemadmodum paene innumera cuiusvis aetatis documenta luculenter testantur. Recentioribus autem temporibus, Sacras Litteras, cum divina earum origo et recta earumdem explanatio peculiari ratione in discrimen vocarentur, maiore etiam alacritate et studio tutandas ac protegendas suscepit Ecclesia. Itaque iam sacrosancta Tridentina Synodus «libros integros cum omnibus suis partibus, -

Paul Vi's Ambivalence Toward Critical Biblical Scholarship

ORGAN OF THE ROMAN THEOLOGICAL FORUM NO. 157 March 2012 PAUL VI’S AMBIVALENCE TOWARD CRITICAL BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP B. INDICATIONS OF APPROVAL: ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS by Brian W. Harrison Having surveyed in Living Tradition, no. 156, what might be called the ‘theoretical’ side of Pope Paul VI’s basic attitude of openness and confidence toward contemporary trends in Catholic biblical scholarship – that is, his writings and speeches expressing that attitude – we will turn now to consider the ‘practical’ side of the same coin. Here we will be looking at the Pope’s exercise of his governing authority rather than his teaching authority. His concrete decisions regarding the ‘hiring and firing’ of certain clerics who would occupy key ecclesiastical positions relating to biblical studies were to have significant ramifications that were perhaps to some extent unexpected by Paul himself. 1. 1960-1962: Tensions within the Vatican over Biblical Studies Probably the most important of these administrative decisions was one taken within the first year of Pope Paul’s pontificate. As a result of controversies over biblical studies in the last years of John XXIII’s pontificate, two prominent Scripture scholars, Maximilian Zerwick, S.J., and Stanislas Lyonnet, S.J., had in 1961 been suspended from teaching at the Pontifical Biblical Institute on account of their exegetical opinions, some of which, in the estimation of the Holy Office, were not in accord with the Church’s Magisterium. However, within one year of the election of Pope Paul VI, both of these professors were re-appointed to teach at the ‘Biblicum’ with the express approval of the new Pontiff. -

The Holy See

The Holy See HOLY MASS TO COMMEMORATE THE 50th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF THE SERVANT OF GOD POPE PIUS XII HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI St Peter's Basilica Thursday, 9 October 2008 Your Eminences, Venerable Brothers in the Episcopate and in the Priesthood, Dear Brothers and Sisters, The passage from the Book of Sirach and the Prologue to St Peter's First Letter, proclaimed as the First and Second Readings, offer us important ideas for reflection at this Eucharistic celebration during which we are commemorating my Venerable Predecessor, the Servant of God Pius XII. Exactly 50 years have passed since his death in the early hours of 9 October 1958. Sirach, as we have heard, reminded whomever intended to follow the Lord that they must prepare themselves to face trials, difficulties and suffering. He recommended that in order not to succumb to them they needed an upright and steadfast heart, patience and fidelity to God as well as firm determination in pursuing the path of good. Suffering refines the heart of the Lord's disciple, just as gold is purified in the crucible: "Accept whatever is brought upon you", the sacred author writes, "and in changes that humble you be patient. For gold is tested in the fire, and acceptable men in the furnace of humiliation" (2: 4-5). In the passage that has been presented to us, St Peter, for his part, goes further when he asked Christians of the communities of Asia Minor, which were being "afflicted by various trials", to "rejoice" in spite of all (1 Pt 1: 6). -

And Post-Vatican Ii (1943-1986 American Mariology)

FACULTAS THEOLOGICA "MARIANUM" MARIAN LffiRARY INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) TITLE: THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF BIBLICAL MARIOLOGY PRE- AND POST-VATICAN II (1943-1986 AMERICAN MARIOLOGY) A thesis submitted to The Theological Faculty "Marianwn" In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology By: James J. Tibbetts, SFO Director: Reverend Bertrand A. Buby, SM Thesis at: Marian Library Institute Dayton, Ohio, USA 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 The Question of Development I. Introduction - Status Questionis 1 II. The Question of Historical Development 2 III. The Question of Biblical Theological Development 7 Footnotes 12 Chapter 2 Historical Development of Mariology I. Historical Perspective Pre- to Post Vatican Emphasis A. Mariological Movement - Vatican I to Vatican II 14 B. Pre-Vatican Emphasis on Scripture Scholarship 16 II. Development and Decline in Mariology 19 III. Development and Controversy: Mary as Church vs. Mediatrix A. The Mary-Church Relationship at Vatican II 31 B. Mary as Mediatrix at Vatican II 37 c. Interpretations of an Undeveloped Christology 41 Footnotes 44 Chapter 3 Development of a Biblical Mariology I. Biblical Mariology A. Development towards a Biblical Theology of Mary 57 B. Developmental Shift in Mariology 63 c. Problems of a Biblical Mariology 67 D. The Place of Mariology in the Bible 75 II. Symbolism, Scripture and Marian Theology A. The Meaning of Symbol 82 B. Marian Symbolism 86 c. Structuralism and Semeiotics 94 D. The Development of Two Schools of Thought 109 Footnotes 113 Chapter 4 Comparative Development in Mariology I. Comparative Studies - Scriptural Theology 127 A. Richard Kugelman's Commentary on the Annunciation 133 B. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

How to Read, Study and Benefit from Papal Encyclicals

How to Read, Study and Benefit from Papal Encyclicals Contents What is an Encyclical ..................................................................................................................................... 1 How to Read and Study an Encyclical ........................................................................................................... 2 Are Encyclicals Infallible Teachings of a Pope ............................................................................................... 2 History of Encyclicals ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Why Read Encyclicals if You are Not Catholic? ............................................................................................. 4 Links to Other Encyclicals and Lists of All Encyclicals ................................................................................... 4 List of Encyclicals ........................................................................................................................................... 4 What is an Encyclical The word encyclical literally means "in a circle." It is a letter intended to travel— to circulate. However in modern times it has become almost exclusively used to denote teachings from the Pope. Comparing an encyclical to other kinds of official Roman Catholic documents is a good way to understand the significance of an encyclical. Firstly, when the pope makes a declaration of some article of faith or moral law it is -

Prek – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018

PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018 Page 1 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 Page 2 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 TABLEU OF CONTENTS PreKU – 8 Course of Study U Introduction .......................................................................................................................7 PreK – 8 Content Structure: Scripture and Pillars of Catechism ..............................9 PreK – 8 Subjects by Grade Chart ...............................................................................11 Grade Pre-K ....................................................................................................................13 Grade K ............................................................................................................................20 Grade 1 ............................................................................................................................29 Grade 2 ............................................................................................................................43 Grade 3 ............................................................................................................................58 Grade 4 ............................................................................................................................72 Grade 5 ............................................................................................................................85 -

Encyclical Letters

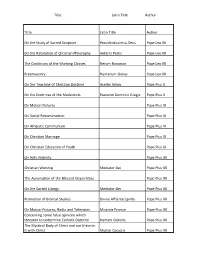

Title Latin Title Author Title Latin Title Author On the Study of Sacred Scripture Providentissimus Deus Pope Leo XII On the Retoration of Christian Philosophy Aeterni Patris Pope Leo XII The Conditions of the Working Classes Rerum Novarum Pope Leo XII Freemasonry Humanum Genus Pope Leo XII On the Teaching of Christian Doctrine Acerbo Nimis Pope Pius X On the Doctrines of the Modernists Pascendi Dominici Gregis Pope Pius X On Motion Pictures Pope Pius XI On Social Reconstruction Pope Pius XI On Atheistic Communism Pope Pius XI On Christian Marriage Pope Pius XI On Christian Education of Youth Pope Pius XI On Holy Virginity Pope Pius XII Christian Worship Mediator Dei Pope Pius XII The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Pope Pius XII On the Sacred Liturgy Mediator Dei Pope Pius XII Promotion of Biblical Studies Divino Afflante Spiritu Pope Pius XII On Motion Pictures, Radio and Television Miranda Prorsus Pope Pius XII Concerning some false opinions which threaten to undermine Catholic Doctrine Humani Generis Pope Pius XII The Mystical Body of Christ and our Union in it with Christ Mystici Corporis Pope Pius XII Title Latin Title Author On the Appearance of the Immaculate Virgin Mary at Lourdes Pope Pius XII False Trends in Modern Teaching Pope Pius XII On the Function of the state in the Modern World Pope Pius XII Re-Evaluation of the Social Question in the light of Christian Teaching Mater et Magistra Pope John XXIII From the Beginning of Our Priesthood Sacerdotii Nostri Primordia Pope John XXIII Christianity and Social Progress Mater