Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Vi on Scripture, Tradition, and Magisterium

ORGAN OF THE ROMAN THEOLOGICAL FORUM NO. 168 JANUARY 2014 PAUL VI ON SCRIPTURE, TRADITION, AND MAGISTERIUM by Brian W. Harrison Part B: Pope Paul’s Personal Magisterial Statements (a) The Continuity of Magisterial Statements on Scripture If we turn now to the addresses of Pope Paul, during and after the Council, which touched on the relationship between Scripture, Tradition and Magisterium, one of the first points which strikes one’s attention is his insistence on continuity between the living Magisterium of the present and the authoritative ‘monuments of tradition’ from the past — both pontifical and patristic. 1. Major Interventions During the Council, at the very time when the second schema on revelation, with its reduced emphasis on Tradition, was being presented to the conciliar Fathers, the Pope made a point of asserting in his first major biblical allocution (25 September 1964) that both Leo XIII’s foundational encyclical of 1893 on biblical studies, and that of Pius XII half a century later, were still both valid and relevant. After commenting that the Church’s criteria for the interpretation of Scripture were well-known to those present, Pope Paul continued: “We shall be content to remind you of how the papal teachings — contained especially in the two great documents ‘Providentissimus Deus’ of Leo XIII and ‘Divino afflante Spiritu’ of Pius XII — are still valid and worthy of the study and adherence of everyone involved in biblical studies.”1 This remark must be seen in the context of influential trends which were giving the impression that Divino afflante Spiritu had virtually superseded all previous magisterial pronouncements on the subject of Sacred Scripture. -

FAITH & Reason

FAITH & REASON THE JOURNAL of CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE Spring 1997 | Vol. XXIII, No. 1 The Encyclical Spiritus Paraclitus in its Historical Context Brian W. Harrison, O.S. I. WAS SPIRITUS PARACLITUS RENDERED OBSOLETE BY DIVINO AFFLANTE SPIRITU? EPTEMBER 1995 MARKED THE SEVENTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF A HIGHLY SIGNIFI- cant document of the Catholic Church’s Magisterium: the Encyclical Letter Spiritus Paraclitus, issued by Pope Benedict XV on September 15, 1920, to mark the 1500th anniversary of the death of the great- est Scripture scholar of the ancient Church, St. Jerome.1 The Pontiff took advantage of that landmark centenary for laying down in this encyclical further norms and guidelines for exegetes, a quarter-century after the promulgation of the great magna carta of modem Catholic biblical studies, Leo XIII’s Encycli- cal Providentissimus Deus (November 18, 1893).1 The Catholic press made little if any mention of the anniversary of Spiritus Paraclitus, which in truth is now an almost forgotten encyclical. Indeed, on the rare occasions when it is remembered at all by to- day’s most prominent Scripture scholars, the context usually appears to be one of disdain for its doctrine and regret for its allegedly negative effect on biblical scholarship. For instance, Fr. Joseph A. Fitzmyer, in a recently published commentary on the 1993 document of the Pontifical Biblical Commission, feels it appropriate to express quite the opposite of gratitude for Spiritus Paraclitus. He does not find Benedict XV’s encyclical worthy of mention in the main text of his historical account of the Catholic biblical movement, but writes in a footnote: If we are grateful today for the encyclicals of Popes Leo XIII and Pius XII on biblical studies, we have to recall that between them there also appeared the encyclical of Pope Benedict XV, Spiritus Paraclitus,.. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A man of extremes - w.g. ward as a member of the church of England Miners, Michael Southworth How to cite: Miners, Michael Southworth (1987) A man of extremes - w.g. ward as a member of the church of England, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6703/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT Michael Southworth Miners M.A. 1987 'A Man of Extremes - V.'.G.. Ward as a Member of The Church of England' The purpose of this thesis is to examine the role of V/.G. Ward in the Oxford Movement, with specific reference to his series of Articles in the British Critic and his book 'The Ideal, of a Christian Church.' In the Introduction we examine Ward's family background, and his early education. -

Article Review Towards a Richer Appreciation of the Oxford Movement

ecclesiology 16 (2020) 243-253 ECCLESIOLOGY brill.com/ecso Article Review ∵ Towards a Richer Appreciation of the Oxford Movement Paul Avis Durham University, Durham, UK, and University of Exeter, Exeter, UK [email protected] Stewart J. Brown, Peter B. Nockles and James Pereiro (eds), (2017) The Oxford Handbook of the Oxford Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. xx + 646 pages, isbn 978-0-19-958018-7 (hbk), £95.00. To read The Oxford Handbook of the Oxford Movement more or less from cover to cover has been a hugely rewarding experience, even though I am no stranger to its subject matter – the history and writings of the movement that cam- paigned to revive a catholic theology, practice and sensibility within the Church of England in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. In engag- ing with this book I am, in a sense, coming home. John Keble’s parochial ministry, John Henry Newman’s epistemology and ecclesiology, and Edward Bouverie Pusey’s sacramental and ecumenical theology have been deeply for- mative for me. And that is the spirit (or ethos in Tractarian-speak, as James Pereiro has shown)1 in which I approach this estimable example of the Oxford Handbook genre. The Oxford (or Tractarian) Movement was a creative upsurge of theological, pastoral and liturgical renewal which lasted from its arresting beginning with John Keble’s Assize Sermon and the first Tracts for the Times in 1833 to John 1 James Pereiro, ‘Ethos’ and the Oxford Movement: At the Heart of Tractarianism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). © paul avis, 2020 | doi:10.1163/17455316-01602007 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by 4.0Downloaded License. -

CORPORATE REUNION: a NINETEENTH- CENTURY DILEMMA VINCENT ALAN Mcclelland University of Hull

CORPORATE REUNION: A NINETEENTH- CENTURY DILEMMA VINCENT ALAN McCLELLAND University of Hull EFORE THE ADVENT of the Oxford Movement in 1833 and before the B young converts George Spencer and Ambrose Phillipps had, shortly before his death, enlisted the powerful support and encouragement of the aristocratic Louis de Quelin, Archbishop of Paris,1 in the establishment in 1838 of an Association of Prayers for the Conversion of England, the matter of the reunion of a divided Christendom had greatly engaged the attention of Anglican divines. Indeed, as Brandreth in his study of the ecumenical ideals of the Oxford Movement has pointed out, "there is scarcely a generation [in the history of the Church of England] from the time of the Reformation to our own day which has not caught, whether perfectly or imperfectly, the vision of a united Christendom."2 The most learned of Jacobean divines, Lancelot Andrewes, Bishop of Winchester under James I, regularly interceded "for the Universal Church, its confir mation and growth; for the Western Church, its restoration and pacifi cation; for the Church of Great Britain, the setting in order of the things that are wanting in it and the strengthening of the things that remain".3 In the anxiety to locate the needs of the national church within the context of the Church Universal, Andrewes was followed by a host of Carolingian divines and Settlement nonjurors, themselves the harbingers of that Anglo-Catholic spirit which gave life, albeit by means of a prolonged and painful Caesarian section, to the vibrant Tractarian quest for ecclesial justification. -

Introduction

Introduction 0.1WhatThisBook Is About This book has adouble goal. The first is to study alargely neglected part of the scientificoeuvreofAlfred Loisy (1857–1940);the second is to use this scholar’s work as awindow into the development and the dynamics of history of religions as ascientific discipline during the first two decades of the 20th century.Best known as the “Father of RomanCatholic Modernism,”¹ this French priest and scholarofancient Judaism and earlyChristianitywas one of the protagonists of the Modernist crisis in the Church in the first decade of the 20th century. Loisy famouslydeveloped an intellectual reform program for aprofound mod- ernization of Catholicism, with the aim to make it more compatible with the re- sults of his critical historical research, and with modern society at large.His reform endeavorwas forcefullyrejected by the Church and led to his excommu- nication in 1908, when he was labelled vitandus. In 1909,after an intenselypo- lemical election campaign, he was appointed to the chair of Histoire des Reli- gions at the CollègedeFrance. There, he developedarich but as yetlargely underexploredcareer as an independent scholar,until his official retirement in 1932. Alfred Loisy’sintellectual legacyhas receiveddetailed scholarlyattention al- most without interruption since the 1960s, when Émile Poulat initiated the mod- ern studyofRomanCatholic Modernism.² Thus far,scholarship has tendedto concentrate on his role in the Modernist crisis, and has predominantlyfocused on his achievementsintheologyand biblical criticism.³ Yet, bothasaCatholic, Amongthe manyscholars whohaveused this expression, see Friedrich Heiler, Alfred Loisy. Der Vater des katholischen Modernismus (München: Erasmus,1947). Seminal studies on Loisy by Poulat include his Histoire, dogme et critique dans la crise mod- erniste (Paris:Casterman, 1979), first published in 1962; and Critique et mystique. -

The Oxford Movement

THE OXFORD MOVEMENT Wonderful is the contrast between the condition of the Catholic Church today and its status a hundred years ago. When the nineteenth century was still young, most of the states men of Europe regarded the Holy See as the feeble remnant of a once great political power, while nearly all Protestants con sidered the Papacy as the work of the Antichrist, and therefore to be shunned like any other evil. Today, the Vatican is a most important factor in the world of diplomacy; and many prom inent sects are making friendly overtures for reunion. This reversal of feeling is due to many complex causes, but in the English-speaking world, nothing has done so much to effect it as that event which is known in the religious history of the last century, as the Oxford Movement. "The Oxford Movement" is the name given to the attempt made by a party of Anglican or Episcopal churchmen in the early nineteenth century to abolish all purely Protestant doctrine which had gradually corrupted the teachings of their Church ; to restore the Catholic faith in all its primitive purity as it was to be found in the works of the early Fathers of the Church, and finally, to free their Church from all state control. These men, with Newman at their head, looked upon the English Establish ment as "The lineal descendant of the Church of Gregory and Augustine, and through them, of the Church of the Apostles." Accordingly they strove to revive those doctrines which had been almost neglected by the Anglican divines of their day. -

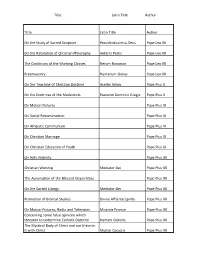

Encyclical Letters

Title Latin Title Author Title Latin Title Author On the Study of Sacred Scripture Providentissimus Deus Pope Leo XII On the Retoration of Christian Philosophy Aeterni Patris Pope Leo XII The Conditions of the Working Classes Rerum Novarum Pope Leo XII Freemasonry Humanum Genus Pope Leo XII On the Teaching of Christian Doctrine Acerbo Nimis Pope Pius X On the Doctrines of the Modernists Pascendi Dominici Gregis Pope Pius X On Motion Pictures Pope Pius XI On Social Reconstruction Pope Pius XI On Atheistic Communism Pope Pius XI On Christian Marriage Pope Pius XI On Christian Education of Youth Pope Pius XI On Holy Virginity Pope Pius XII Christian Worship Mediator Dei Pope Pius XII The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Pope Pius XII On the Sacred Liturgy Mediator Dei Pope Pius XII Promotion of Biblical Studies Divino Afflante Spiritu Pope Pius XII On Motion Pictures, Radio and Television Miranda Prorsus Pope Pius XII Concerning some false opinions which threaten to undermine Catholic Doctrine Humani Generis Pope Pius XII The Mystical Body of Christ and our Union in it with Christ Mystici Corporis Pope Pius XII Title Latin Title Author On the Appearance of the Immaculate Virgin Mary at Lourdes Pope Pius XII False Trends in Modern Teaching Pope Pius XII On the Function of the state in the Modern World Pope Pius XII Re-Evaluation of the Social Question in the light of Christian Teaching Mater et Magistra Pope John XXIII From the Beginning of Our Priesthood Sacerdotii Nostri Primordia Pope John XXIII Christianity and Social Progress Mater -

Scarica Il Quarto Volume In

Dizionario storico dell’Inquisizione vol. IV PISA NORMALE diretto da Adriano Prosperi con la collaborazione di Vincenzo Lavenia e John Tedeschi SCUOLA SUPERIORE 2010EDIZIONI DELLA © NORMALE Comitato scientifico Michele Battini, Università di Pisa Jean-Pierre Dedieu, LARHRA CNRS – Lyon Roberto López Vela, Universidad de Cantábria Grado G. Merlo, Università Statale di Milano José Pedro Paiva, Universidade de Coimbra PISA Adriano Prosperi, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa John Tedeschi, University of Wisconsin – Madison WI NORMALE Comitato editoriale Matteo Al Kalak, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa Vincenzo Lavenia, Università di Macerata Adelisa Malena, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Giuseppe Marcocci, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa Francesco Mores, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa Stefania Pastore, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa Redazione Francesca Di Dio Traduzioni Paolo Broggio (spagnolo) Andrea Pardi (portoghese) Katia Pischedda (tedesco) Martina Urbaniak (francese,SCUOLA inglese) Indici Gian Mario Cao Marco Cavarzere Francesca Dell’Omodarme Letizia Pellegrini SUPERIORE Apparato iconografico Chiara Franceschini © 20102010 Scuola Normale Superiore Pisa isbn 978-88-7642-323-9 (opera completa) La copia digitale dell’opera è a uso esclusivo degli autori. ©Vietata la riproduzione e la vendita. Elenco delle voci Abad y La Sierra, Manuel M. Torres Arce Abilitazioni J.-P. Dedieu Abitello v. Sambenito Abiura E. Brambilla Abolizione dei tribunali, Italia A. Borromeo Abolizione del tribunale, Portogallo P. Drumond Braga Abolizione del tribunale, Spagna R. Muñoz Solla Aborto E. Betta Abrunhosa, Gastão de G. Marcocci PISA Abuso di sacramenti e sacramentali A. Prosperi Accusa v. Denuncia Acordadas NORMALEv. Lettere circolari Acqui v. Alessandria Action française I. Pavan Acton, John Emerich Edward Dalberg G. Crosignani Ad abolendam G.G. -

Newman, Conversion, and Ecumenism Avery Dulles, S.J

Theological Studies 51 (1990) NEWMAN, CONVERSION, AND ECUMENISM AVERY DULLES, S.J. Fordham University HE CENTENARY of Cardinal Newman's death, on Aug. 11, 1890, has Toccasioned a large number of conferences and studies dealing with various aspects of his work. The present article is intended as a part of this commemoration. As one who came to the Catholic faith in adult life, Newman reflected long and deeply about his own religious pilgrimage and became the adviser of many companions and followers. He therefore deserves to be remembered as one of the great theologians of conversion. Because of his comprehensive vision of Christianity as a whole and his lifelong concern with overcoming Christian divisions, he has also been hailed as a forerunner of ecumenism.1 His observations on Christian unity in some respects anticipate the directions of the Second Vatican Council. But there was in his thinking a tension between the convert and the ecumenist, the apologist for Catholicism and the friendly observer of other Christian communions. His efforts to be faithful to his dual vocation as a convert and as an ecumenist make his thought particularly relevant today, when a number of distinguished ecumenists, without loss of their ecumenical commitment, have felt the call to enter into full communion with the Church of Rome. THE CONVERT Newman's conversion was slow, deliberate, and painful, but by no means halfhearted. For more than five years, from 1839 to 1845, he felt an increasing realization that the Church of England, to which he belonged, was not a part of the Catholic Church. -

Autographes & Manuscrits

_25_06_15 AUTOGRAPHES & MANUSCRITS & AUTOGRAPHES Pierre Bergé & associés Société de Ventes Volontaires_agrément n°2002-128 du 04.04.02 Paris 92 avenue d’Iéna 75116 Paris T. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 00 F. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 01 Bruxelles Avenue du Général de Gaulle 47 - 1050 Bruxelles Autographes & Manuscrits T. +32 (0)2 504 80 30 F. +32 (0)2 513 21 65 PARIS - JEUDI 25 juIN 2015 www.pba-auctions.com VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES PARIS Pierre Bergé & associés AUTOGRAPHES & MANUSCRITS DATE DE LA VENTE / DATE OF THE AUCTION Jeudi 25 juin 2015 - 13 heures 30 June Thursday 25th 2015 at 1:30 pm LIEU DE VENTE / LOCATION Drouot-Richelieu - Salle 8 9, rue Drouot 75009 Paris EXPOSITION PRIVÉE / PRIVATE VieWinG Sur rendez-vous à la Librairie Les Autographes 45 rue de l’Abbé Grégoire 75006 Paris T. + 33 (0)1 45 48 25 31 EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES / PUBlic VieWinG Mercredi 24 juin de 11 heures à 18 heures Jeudi 25 juin de 11 heures à 12 heures June Wednesday 24th from 11:00 am to 6:00 pm June Thursday 25th from 11:00 am to 12:00 pm TÉLÉPHONE PENDANT L’EXPOSITION PUBLIQUE ET LA VENTE T. +33 (0)1 48 00 20 08 CONTACTS POUR LA VENTE Eric Masquelier T. + 33 (0)1 49 49 90 31 - [email protected] Sophie Duvillier T. + 33 (0)1 49 49 90 10 - [email protected] EXPERT POUR LA VENTE Thierry Bodin Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en Œuvres d'Art 45 rue de l'Abbé Grégoire, 75006 Paris T. -

Loisy's Theological Development Valentine G

LOISY'S THEOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT VALENTINE G. MORAN, S.J. Campion College, Victoria, Australia N DECEMBER 1903 the Congregation of the Holy Office added five I works of Alfred Loisy to its Index of Prohibited Books1 and made their author widely known. Up to this time the Abbé Loisy had written most of his articles and books for seminarians and priests, or for scholars engaged in his own field of biblical studies. He was hardly known to the general public of France; even the Catholic public had only recently begun to hear of him. He wrote about the Scriptures and the questions that critics, particularly in Germany, had been asking for over fifty years about their truth, authorship, and inspiration; and his readiness to accept many of the answers which the critics offered had put him squarely among a small group of Catholic scholars in Europe who wanted to adapt the Church's teaching to the contemporary world, to have the Church absorb, not reject, the results of scientific research that had a bearing on religion and especially on Christianity. Loisy's writing had caused trouble with his superiors before 1903. He had been forced to resign his chair of Scripture at the Institut Catholique of Paris in 1893; in 1900 the Archbishop of Paris forbade the Revue du clergé français2 to publish anything he wrote.3 By that time what had reached the clergy, especially the younger priests, was through them beginning to reach the laity, and the publication by Loisy of several radical articles between 1898 and 1903 caused controversy in the Catholic press.