SECURITIES MCDONALDS DERIVATIVE SUIT Complaint.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Change of Representative Directors

October 30, 2020 Shiseido Company, Limited Notice of Change of Representative Directors Shiseido Company, Limited (the “Company”) hereby announces that it has decided to implement a change in its Representative Directors at the Board of Directors meeting held on October 29, as detailed below. 1. Name and Title of Retiring Representative Director Name: Yoichi Shimatani Current Title: Representative Director, Executive Vice President New Title: Director 2. Name and Title of Newly Appointed Representative Director Name: Yukari Suzuki Current Title: Director, Executive Corporate Officer New Title: Representative Director, Executive Corporate Officer 3. Reasons for the Change The Company sets an upper age limit per position for corporate officers based on its internal rules. In accordance with this basic principle, Yoichi Shimatani will retire from the position of Executive Vice President as of December 31, 2020, and as a result, he will also retire as Representative Director on the same date. Yukari Suzuki, who will newly assume the office of Representative Director as from January 1, 2021, has built a long career at the Company and possesses a vast experience mainly in fields of marketing and brand development. She has also led the global growth of Clé de Peau Beauté, one of the Company’s representative brands. Given her remarkable achievements in nurturing prestige brands, key contributors to corporate performance, Ms. Suzuki is expected to successfully drive the growth of the business while assisting the management overall. Furthermore, the Company recognizes the need to promote diversity among its management, and thus has decided to appoint Ms. Suzuki to the new position. As a result, the Company will maintain two representative directors. -

Chief Brand Officer Ed Romaine Edward Romaine Is a Proven Sales

Chief Brand Officer Ed Romaine Edward Romaine is a proven sales and branded content lead executive with more than 15 years of experience overseeing the development and implementation of advertising solutions across digital, mobile, video, social, experiential and print platforms. Ed sets himself apart not only the through his curation of great agency and client-direct relationships but also through core competencies including team building, ideation, monetization, detail-oriented sell through and execution as well as overarching brand strategy. Beginning his career in the music industry at Warner Music Group, Ed also optimized campaign performances for many Fortune 500 clients at Alloy Media+Marketing, Bauer Media Group and Hearst Media Corporation before serving five years at Conde Nast, overseeing Integrated Marketing + Sales Development at both W and GQ US divisions. In 2016, Ed was appointed Chief Marketing Officer at Kargo Global. His org at the company included product marketing, strategy, research, pr/social communications, creative services and global experiences. He hosted a podcast, Mobilizing Culture, available on iTunes and Google Play. Ed joined Bleacher Report in 2018 as Chief Brand Officer, overseeing all of the company's marketing efforts, to build on investments to grow the preeminent sports culture brand. He also oversees the experience, brand, and design teams helping to consistently bring to life initiatives emanating from B/R’s content, operations, sales, and other key business groups. He lives in New York City with his husband and is a consistent mediator for his family who has dueling sports allegiances of Boston and Philly. . -

1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION VICTORIA GUSTER-HINES and DOMINECA NEAL, P

Case: 1:20-cv-00117 Document #: 1 Filed: 01/07/20 Page 1 of 103 PageID #:1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION VICTORIA GUSTER-HINES and DOMINECA NEAL, Plaintiffs, vs. Case No. McDONALD’S USA, LLC, a Delaware limited liability company, Jury Trial Demanded McDONALD’S CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation, STEVEN EASTERBROOK, CHRISTOPHER KEMPCZINSKI, and CHARLES STRONG Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR DEPRIVATIONS OF CIVIL RIGHTS Plaintiffs, Victoria Guster-Hines and Domineca Neal, by attorneys Carmen D. Caruso and Linda C. Chatman, bring suit under the Civil Rights Act of 1870 (42 U.S.C. §1981) against Defendants McDonald’s USA, LLC, McDonald’s Corporation, Steven Easterbrook, Christopher Kempczinski, and Charles Strong to redress intentional race discrimination, disparate treatment, hostile work environment and unlawful retaliation. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs Vicki Guster-Hines and Domineca Neal are African American senior executives at McDonald’s USA, LLC, the franchisor of the McDonald’s 1 Case: 1:20-cv-00117 Document #: 1 Filed: 01/07/20 Page 2 of 103 PageID #:1 restaurant system in the United States. They bring suit to redress McDonald’s continuing pattern and practice of intentional race discrimination that should outrage everyone, especially those who grew up going to McDonald’s and believing the “Golden Arches” were swell. 2. Vicki joined McDonald’s in 1987 and Domineca joined McDonald’s in 2012. They are highly qualified, high-achieving franchising executives, but McDonald’s subjected them to continuing racial discrimination and hostile work environment impeding their career progress, even though they both did great work for McDonald’s, which the Company consistently acknowledged in their performance reviews. -

Mcdonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1994 Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985 Kathleen D. Toerpe Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Toerpe, Kathleen D., "Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985" (1994). Dissertations. 3457. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3457 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1994 Kathleen D. Toerpe LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SMALL FRY, BIG SPENDER: MCDONALD'S AND THE RISE OF A CHILDREN'S CONSUMER CULTURE, 1955-1985 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY KATHLEEN D. TOERPE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY, 1994 Copyright by Kathleen D. Toerpe, 1994 All rights reserved ) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank McDonald's Corporation for permitting me research access to their archives, to an extent wider than originally anticipated. Particularly, I thank McDonald's Archivist, Helen Farrell, not only for sorting through the material with me, but also for her candid insight in discussing McDonald's past. My Director, Lew Erenberg, and my Committee members, Susan Hirsch and Pat Mooney-Melvin, have helped to shape the project from its inception and, throughout, have challenged me to hone my interpretation of McDonald's role in American culture. -

Regiocentric Orientation Strategy in Fast Food Chain

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668. Volume 17, Issue 8.Ver. I (Aug. 2015), PP 01-04 www.iosrjournals.org Regiocentric orientation strategy in fast food chain Prof. Kunal Bhanubhai Upadhyay BBA Faculty, SRK Institute of Management & Computer Education, Sapeda-Anjar (Gujarat). India. Abstract: Fast food restaurants usually have a seating area in which customers can eat the food on the premises, orders are designed to be taken away, and traditional table service is rare. Orders are generally taken and paid for at a wide counter, with the customer waiting by the counter for a tray or container for their food. A "drive-through" service can allow customers to order and pick up food from their cars. Nearly from its inception, fast food has been designed to be eaten "on the go" and often does not require traditional tableware and is eaten as a finger food. Common menu items at fast food outlets include fish and chips, sandwiches, pitas, hamburgers, fried chicken, french fries, chicken nuggets, tacos, pizza, and ice cream, although many fast food restaurants offer "slower" foods like chili, mashed potatoes, and salads. McDonald's in the United States will have the same experience as someone visiting a McDonald's in Japan. The interior design, the menu, the speed of service, and the taste of the food will all be very similar. However, some differences do exist to modify to particular cultural differences. I. Introduction Mcdonald’s & Its Global Strategies The purpose of this document is to analyze the existence of McDonald’s Corporation and its Global Strategies. -

Antero Maximiliano Dias Dos Reis Mcdonald's

ANTERO MAXIMILIANO DIAS DOS REIS MCDONALD’S: A DURA FACE DO TRABALHO FLEXÍVEL NO MUNDO JUVENIL (FLORIANÓPOLIS, 2000-2007) FLORIANÓPOLIS – SC 2009 Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DE SANTA CATARINA - UDESC CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E DA EDUCAÇÃO – CCE/FAED PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA ANTERO MAXIMILIANO DIAS DOS REIS MCDONALD’S: A DURA FACE DO TRABALHO FLEXÍVEL NO MUNDO JUVENIL (FLORIANÓPOLIS, 2000-2007) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, como requisito para obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Orientadora: Dra. Sílvia Maria Fávero Arend FLORIANÓPOLIS – SC 2009 2 ANTERO MAXIMILIANO DIAS DOS REIS MCDONALD’S: A DURA FACE DO TRABALHO FLEXÍVEL NO MUNDO JUVENIL (FLORIANÓPOLIS, 2000-2007) Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre, no curso de Pós-Graduação em História na Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina. Banca Examinadora: Orientadora:_______________________________________________________ Dra. Sílvia Maria Fávero Arend Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina Membro: _________________________________________________________ Dra. Cristiani Bereta da Silva Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina Membro: _________________________________________________________ Dra. Esmeralda Blanco Bolsonaro de Moura Universidade de São Paulo FLORIANÓPOLIS, fevereiro de 2009. 3 Dedico à Sônia, Patrícia e Jade. 4 AGRADECIMENTOS: Gratidão, esta palavra-tudo. Agradeço, primeiramente, a minha estimada orientadora: Professora Doutora Sílvia Maria Fávero Arend, por ter acreditado e confiado na possibilidade da realização desta pesquisa, por tê-la tornado realmente possível. Agradeço- lhe por esta difícil tarefa que é orientar, por sua ajuda, dedicação e interesse. Agradeço à Professora Doutora Cristiani Bereta da Silva, que tem me oportunizado ideias valorosas com seu conhecimento e sensibilidade. -

Diplomova Prace

VYSOKÉ U ČENÍ TECHNICKÉ V BRN Ě BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY FAKULTA PODNIKATELSKÁ ÚSTAV EKONOMIKY FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS ŘÍZENÍ LIDSKÝCH ZDROJ Ů U MCDONALD‘S MCDONALD'S HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE MASTER’S THESIS AUTOR PRÁCE JAN POPELÁ Ř AUTHOR VEDOUCÍ PRÁCE PHDR. ING. JI ŘÍ POKORNÝ, CSC. SUPERVISOR BRNO 2008 Anotace Diplomová práce se zabývá problematikou řízení lidských zdroj ů v restauraci McDonald‘s. Práce je rozd ělena na dv ě části. První část je teoretická a vymezuje všechny základní pojmy. Praktická část se dále d ělí na analytickou, v níž najdeme informace o spole čnosti Baierová spol. s r.o. a návrhovou, která se zabývá dalšími možnostmi motivace a implementaci nové motiva ční metody. V záv ěru potom najdeme odhad p řínosu pro firmu a zhodnocení. Annotation Master’s thesis solves the question of human resource management in the McDonald’s restaurant. My thesis has two main parts. The first is desk study with fundamental terms. Practical part forks on first analysis part, where you can find information about the company, and second concept part, which considers about next motivation possibilities and implementation of new motivation method. In the end of the thesis you can find income estimation and complete evaluation. Klí čová slova: řízení lidských zdroj ů, motivace, franšízing, vedení lidí, systém odm ěn. human resource management, motivation, franchising, human leadership, bonus system. Bibliografická citace mé práce: POPELÁ Ř, J. Řízení lidských zdroj ů u McDonald‘s. Brno: Vysoké u čení technické v Brn ě, Fakulta podnikatelská, 2008. 93 s. Vedoucí diplomové práce PhDr. -

| CES 2020 Las Vegas, January 6-10

| CES 2020 Las Vegas, January 6-10 *OMNICOM-HOSTED SUITES: 1/6-1/8 OPMG SUITE: WELCOME TO LAS VEGAS Venue: Aria Sky Suites at CES C-Space 1/6-1/9 HEARTS & SCIENCE SUITE Venue: The Bellagio (suite number TBA) TH MONDAY, JANUARY 6 3:00pm-3:45pm THE HIDDEN DIVERSITY DIVIDEND Antonio Lucio, Chief Marketing Officer, Facebook Venue: Aria, Level 3, Ironwood Ballroom 8:30pm DAIMLER KEYNOTE ADDRESS Ola Källenius, Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler AG, Head of Mercedes-Benz Venue: Park Theater at Park MGM Hotel TH TUESDAY , JANUARY 7 9:00am-10:00am CHIEF PRIVACY OFFICER ROUNDTABLE: WHAT DO CONSUMERS WANT? Jane Horvath, Senior Director, Global Privacy, Apple Erin Egan, Public Policy and Chief Privacy Officer for Policy, Facebook Susan Shook, Global Privacy Officer, P&G Venue: LVCC, North Hall, N257 9:15am-9:55am SCALING SUCCESS IN CONNECTED TV Kate Brady, Head of Media Innovation & Partnership Development, PepsiCo Venue: Aria, Level 3, Juniper 1 1:00pm-2:00pm GETTING TO AND MONETIZING 5G Mo Katibeh, EVP, Chief Marketing Officer, AT&T Venue: LVCC, North Hall, N262 Continues on next page 1 1:25pm-1:50pm WE’VE DIGITALLY TRANSFORMED…NOW WHAT? Melinda Richter, Global Head of JLABS, Johnson & Johnson Venue: Venetian, Level 4, Lando 4305 2:15pm-3:15pm PEOPLE, DATA AND TECHNOLOGY: NEW MARKETING INNOVATIONS Sarita Rao, SVP, Business Marketing, Analytics and Alliances, AT&T Venue: Aria, Level 3, Juniper 1 3:00pm-3:45pm THE NEXT GENERATION OLYMPICS Chris Curtin, Chief Brand & Innovation Marketing Officer, Visa Venue: Aria, Level 3, Ironwood Ballroom -

Nov. 5, 2018 Changes Among Directors, Audit

(Translation) November 5, 2018 Dear Sirs and Madams, Name of Company: Shiseido Company, Limited Name of Representative: Masahiko Uotani President and CEO (Representative Director) (Code No. 4911; The First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange) Contact: Harumoto Kitagawa Department Director Investor Relations Department (Tel: +81 3 3572 5111) Changes among Directors, Audit & Supervisory Board Members and Corporate Officers We hereby announce the following changes of executives effective on and after January 1, 2019. (1) Retiring Representative Director and Corporate Officer (December 31, 2018) Name Current Title Note Jun Aoki Representative Director, To become Director, Corporate Executive Officer Executive Corporate Officer as of Jan.1, 2019 Masaya Hosaka Corporate Officer ― Mikiko Soejima Corporate Officer ― (2) New Representative Director and Promotion of Corporate Officer (Effective January 1, 2019) Name New Title Current Title Yoichi Shimatani Representative Director Director Executive Vice President Corporate Executive Officer (3) New Corporate Officers (Effective January 1, 2019) Name New Title Current Title Michael Coombs Corporate Officer From outside the company (Refer to appendix) Kiyomi Horii Corporate Officer Corporate Officer Vice President, Prestige Brands, Prestige Brands & Cosmetics Specialty Store, Shiseido Japan Co., Ltd. 1 Terufumi Yorita Corporate Officer Global General Counsel Department Director, Legal & Governance Department Director, Risk Management Department Katsunori Yoshida Corporate Officer Center Director, Cosmetics R&D Center, Global Innovation Center (4) Corporate Officer with extended term (Effective January 1, 2019) Name Current Title Note Mitsuru Kameyama Corporate Officer Term extension of 2nd year beyond the age limit of 60*1 *1 Mitsuru Kameyama has made achievements in the field of information communication technology, including the formulation of the “One Shiseido Model,” a platform that will be used to realize full-fledged global management, and the launch of the project for the Model in cooperation with each region. -

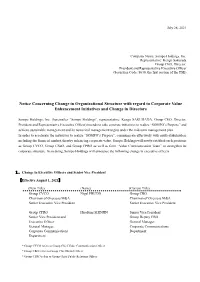

Notice Concerning Change in Organizational Structure with Regard to Corporate Value Enhancement Initiatives and Change in Directors

July 28, 2021 Company Name: Sompo Holdings, Inc. Representative: Kengo Sakurada Group CEO, Director, President and Representative Executive Officer (Securities Code: 8630, the first section of the TSE) Notice Concerning Change in Organizational Structure with regard to Corporate Value Enhancement Initiatives and Change in Directors Sompo Holdings, Inc. (hereinafter “Sompo Holdings”, representative: Kengo SAKURADA, Group CEO, Director, President and Representative Executive Officer) intends to take concrete initiatives to realize “SOMPO’s Purpose” and achieve sustainable management and its numerical management targets under the mid-term management plan. In order to accelerate the initiatives to realize “SOMPO’s Purpose”, communicate effectively with multi-stakeholders including the financial market, thereby enhancing corporate value, Sompo Holdings will newly establish such positions as Group CVCO, Group CSuO, and Group CPRO as well as form “Value Communication Team” to strengthen its corporate structure. In so doing, Sompo Holdings will announce the following change in executive officers. 1.Change in Executive Officers and Senior Vice President 【Effective August 1, 2021】 (New Title) (Name) (Current Title) Group CVCO Nigel FRUDD Group CBO Chairman of Overseas M&A Chairman of Overseas M&A Senior Executive Vice President Senior Executive Vice President Group CPRO Hirofumi SHINJIN Senior Vice President Senior Vice President and Group Deputy CBO Executive Officer General Manager, General Manager, Corporate Communications Corporate Communications Department Department * Group CVCO refers to Group Chief Value Communication Officer. * Group CBO refers to Group Chief Brand Officer. * Group CPRO refers to Group Chief Public Relations Officer. 2.Appointment of Senior Vice President and Executive Officer 【Effective August 1, 2021】 (New Title) (Name) (Current Title) Group CSuO Ryoko SHIMOKAWA Deputy General Manager, Senior Vice President and Healthcare Business Development ホ Executive Officer * Group CSuO refers to Group Chief Sustainability Officer. -

Marketing Moves: H1 2020

Marketing Moves: H1 2020 To better understand current trends in the appointment and turnover of marketing officers, Russell Reynolds Associates tracked and analyzed 241 notable, publicly disclosed marketing leadership moves from January to June 2020. 2 Marketing Moves Jump by 15 Percent Despite COVID-19 COVID-19 has presented ongoing challenges to marketers as massive uncertainty, economic slowdowns and public health concerns persist. The initial wave of COVID caused a number of firms to slash their marketing spend, due to live TV and outdoor advertising grinding to a halt. Across the globe, marketing teams were reduced in size, and the big question on everyone’s lips was: Where is the future of marketing heading? To our surprise, the reduction in marketing spend during COVID did not translate into a reduction in executive marketing leadership moves. In fact, between January and June 2020, we have seen an increase in marketing moves by 15 percent at the senior-most level versus the same period a year ago. KEY FINDINGS ɳ Marketers have moved jobs during this crisis. The first half of NUMBER OF MOVES YOY 2020 saw a record number of marketing moves since we started tracking job changes in 2013. In total, there were 241 publicly- 241 announced marketing executive moves, up from 214 in the 209 214 second half and 209 in the first half of 2019. Not surprisingly, this 173 pandemic has given the technology sector a boost, accounting for 27 percent of all marketing moves in the first six months of 2020, with 65 new marketers hired into technology companies. -

Mcdonald's Corporation

MH0037 1259420477 REV: SEPTEMBER 14, 2015 FRANK T. ROTHAERMEL MARNE L. ARTHAUD-DAY McDonald’s Corporation SEPTEMBER 1, 2015. Steve Easterbrook walked into his office in McDonald’s corporate headquar- ters. He had finally achieved his dream of becoming chief financial officer (CEO) at a major Fortune 500 company, but somehow he had expected it to feel better than this. Don Thompson, the former CEO who had recently “retired” had not been just his boss, but his friend. They had both started their careers at McDonald’s early in the 1990s and had climbed the corporate ladder together. He had not taken personal joy in seeing either his friend or his company fail. Rather, Easterbrook had fantasized about inheriting the company at its peak and taking it to new heights—not finding the corporate giant on its knees in desperate need of a way to get back up. The company’s troubles had snowballed quickly. In 2011, McDonald’s had outperformed nearly all of its competitors while riding the recovery from a deep economic recession. In fact, McDonald’s was the number-one performing stock in the Dow 30 with a 34.7 percent total shareholder return.1 But in 2012, McDonald’s dropped to number 30 in the Dow 30 with a –10.75 percent return. The company went from first to last in 12 brief months (see Exhibits 1 and 2). In October 2012, McDonald’s sales growth dropped by 1.8 percent, the first monthly decline since 2003.2 Annual system-wide sales growth in 2012 barely met the minimum 3 percent goal, while operating income growth was just 1 percent (compared to a goal of 6 to 7 percent).3 Sales continued to decline over the next two years.