The African Element in Gandhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

Gandhi Sites in Durban Paul Tichmann 8 9 Gandhi Sites in Durban Gandhi Sites in Durban

local history museums gandhi sites in durban paul tichmann 8 9 gandhi sites in durban gandhi sites in durban introduction gandhi sites in durban The young London-trained barrister, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 1. Dada Abdullah and Company set sail for Durban from Bombay on 19 April 1893 and arrived in (427 Dr Pixley kaSeme Street) Durban on Tuesday 23 May 1893. Gandhi spent some twenty years in South Africa, returning to India in 1914. The period he spent in South Africa has often been described as his political and spiritual Sheth Abdul Karim Adam Jhaveri, a partner of Dada Abdullah and apprenticeship. Indeed, it was within the context of South Africa’s Co., a firm in Porbandar, wrote to Gandhi’s brother, informing him political and social milieu that Gandhi developed his philosophy and that a branch of the firm in South Africa was involved in a court practice of Satyagraha. Between 1893 and 1903 Gandhi spent periods case with a claim for 40 000 pounds. He suggested that Gandhi of time staying and working in Durban. Even after he had moved to be sent there to assist in the case. Gandhi’s brother introduced the Transvaal, he kept contact with friends in Durban and with the him to Sheth Abdul Karim Jhaveri, who assured him that the job Indian community of the City in general. He also often returned to would not be a difficult one, that he would not be required for spend time at Phoenix Settlement, the communitarian settlement he more than a year and that the company would pay “a first class established in Inanda, just outside Durban. -

South Africa

South Africa South Africa has a long history. Since a lot of human beings look at my words, I have decided to write on this issue since the recent events going on in the country of South Africa. Its history begins with black human beings as the first human beings on Earth in the great continent of Africa are black. It is found in the southern tip of Africa. It has been in the international news a lot lately. Many viewers here are from South Africa, so I decided to write about South Africa. It has over 51 million human beings living there. Its population is mostly black African in about 80% of its population, but it is still highly multiethnic. Eleven languages are recognized in the South African constitution. All ethnic and language groups have political representation in the country's constitutional democracy. It is made up of a parliamentary republic . Unlike most Parliamentary Republics, the positions of head of State and head of government are merged in a parliament-dependent President. South Africa has the largest communities of European, Asian, and racially mixed ancestry in Africa. The World Bank calls South Africa as an upper middle income economy. It has the largest economy in Africa. South Africa has been through a lot of issues in the world. Also, South Africa can make a much better future. Apartheid is gone, which is a good thing. It is good to not see reactionary mobs and the police to not massively kill university students in Soweto. It is good to not allow certain papers dictate your total travels. -

The Colonial-Born and Settlers' Indian Association and Natal Indian Politics 1933-1939

THE COLONIAL-BORN AND SETTLERS' INDIAN ASSOCIATION AND NATAL INDIAN POLITICS 1933-1939 by ANAND CHEDDIE Sub.ltted In partial tultll.ent of the require.ents tor the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Depart.ent of HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NATAL SUPERVISOR: Professor P. R. Warhurst DECEMBER 1992, DURBAN ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to examine Indian political development in South Africa during the period 1933-1939, with specific reference to the emergence of the Colonial-Born and Settlers' Indian Association and its influence on the course of Natal Indian politics. The primary aim of the thesis is to examine the role played by this Association in obstructing the Union government's assisted emigration plans and colonisation scheme. To achieve this aim it was necessary to examine the establishment of the Association and to determine whether the Association fulfilled its main objective. After a brief exposition of early Indian immigration, the activities of the successive Agent-Generals are examined in the context of their relationship with the Natal Indi~n Congress (NIC) and the Association and how these diplomats articulated the aspirations of their government. The Agency at tempted to secure improvements in the socio-economic position of the South African Indian community. In terms of various directives from the Indian government it was clear that they emphasised the value of negotiations and compromise and aggressively suppressed the strategies of those who opposed this approach. This attitude surfaced particularly in its relationship with the Association relative to the Association's stance on the colonisation issue. Notwitstanding the disabilities experienced by the Association in its fight for the equal status of its supporters and for the right to remain in South Africa, the Association is seen to have succeeded in the realisation of its fundamental objective. -

The Phoenix Settlement - Ulwazi the Phoenix Settlement the Phoenix Settlement

6/26/2011 The Phoenix Settlement - Ulwazi The Phoenix Settlement The Phoenix Settlement From Ulwazi Contents 1 Communal Settlement 2 Phoenix Settlement Trust 3 Indian Opinion 4 Private School 5 Gandhi's legacy continued 6 The settlement restored 7 Gandhi honoured 8 Sources Communal Settlement The Phoenix Settlement, established by Mahatma Gandhi in 1904, is situated on the north-western edge of Inanda, some 20 kilometres north of Durban. Sita Gandhi writes “my grandfather’s farm … was fifteen miles away from the city, and in those days around us were plantations of sugar cane fields. Over 100 acres of land was called Phoenix Settlement. It was the most beautiful piece of land, untouched by the then racial laws.” The Settlement, devoted to Gandhi's principles of Satyagraha (passive resistance) has played an important spiritual and political role throughout its long history, promoting justice, peace and equality. Gandhi established the settlement as an communal experimental farm with the view of giving each family two acres of land which they could develop. He believed that communities like Phoenix which advocated communal living would form a sound bsis for the struggle against social injustice. His granddaughter Ela Gandhi points out that Gandhi used the Settlement "to train political activists called satyagrahis as well as house their families, while they were engaged in the campaigns against unjust laws". Her sister Sita describes the Phoenix Settlement as a lively, bustling community, a veritable kutum. Market gardens were established, their diary supplied milk to all the homesteads on the settlement as well as the neighbourhood, and they produced their own butter and ghee for domestic use. -

The Futility of Violence I. Gandhi's Critique of Violence for Gandhi, Political

CHAPTER ONE The Futility of Violence I. Gandhi’s Critique of Violence For Gandhi, political life was, in a profound and fundamental sense, closely bound to the problem of violence. At the same time, his understanding and critique of violence was multiform and layered; violence’s sources and consequences were at once ontological, moral and ethical, as well as distinctly political. Gandhi held a metaphysical account of the world – one broadly drawn from Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist philosophy – that accepted himsa or violence to be an ever-present and unavoidable fact of human existence. The world, he noted, was “bound in a chain of destruction;” the basic mechanisms for the reproduction of biological and social life necessarily involved continuous injury to living matter. But modern civilization – its economic and political institutions as well as the habits it promoted and legitimated – posed the problem of violence in new and insistent terms. Gandhi famously declared the modern state to represent “violence in a concentrated and organized form;” it was a “soulless machine” that – like industrial capitalism – was premised upon and generated coercive forms of centralization and hierarchy.1 These institutions enforced obedience through the threat of violence, they forced people to labor unequally, they oriented desires towards competitive material pursuits. In his view, civilization was rendering persons increasingly weak, passive, and servile; in impinging upon moral personality, modern life degraded and deformed it. This was the structural violence of modernity, a violence that threatened bodily integrity but also human dignity, individuality, and autonomy. In this respect, Gandhi’s deepest ethical objection to violence was closely tied to a worldview that took violence to inhere in modern modes of politics and modern ways of living. -

Gandhi and Sexuality: in What Ways and to What Extent Was Gandhi’S Life Dominated by His Views on Sex and Sexuality? Priyanka Bose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The South Asianist Journal Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 137 Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose [email protected] Though research is coming to light about Gandhi’s views on sexuality, there is still a gap in how this can be related or focused to his broader political philosophy and personal conduct. Joseph Alter states: “It is well known that Gandhi felt that sexuality and desire were intimately connected to social life and politics and that self-control translated directly into power of various kinds both public and private.”* However, I would argue, that the ways in which Gandhi connected these aspects, why and how, have not been fully discussed and are, indeed, not well known. By studying his views and practices with relation to sexuality, I believe that much can be discerned as to how his political philosophy and personal conduct were both established and acted out. In this paper I will aim, therefore, to address: what his views were on sex and sexuality, contextualizing his views with those of the time, what his influences were in his ideology on sex, and how these ideologies framed and related to his political philosophy as well as conduct. -

Gandhi's Swaraj

PERSPECTIVE when his right hand got tired he used his Gandhi’s Swaraj left hand. That physical tiredness did not d iminish Gandhi’s powers of concentra- tion was evident from the fact that the Rudrangshu Mukherjee manuscript had only 16 lines that had been deleted and a few words that had This essay briefl y traces Gandhi’s “I am a man possessed by an idea’’ – Gandhi been altered.3 to Louis Fischer in 1942. The ideas presented in that book grew ideas about swaraj, their “I made it [the nation] and I unmade it” out of Gandhi’s refl ection, his reading and articulation in 1909 in Hind – G andhi to P C Joshi in 1947. “I don’t want to die a failure. But I may be a his experiences in South Africa. It is sig- Swaraj, the quest to actualise failure” – Gandhi to Nirmal Bose in 1947.1 nifi cant that when he wrote Hind Swaraj, these ideas, the turns that history Gandhi had not immersed himself in Indi- gave to them, and the journey n the midnight of 14-15 August an society and politics. His experiments in that made Mohandas 1947, when Jawaharlal Nehru, the India still lay in the future. In fact, Hind Ofi rst prime minister of India, Swaraj served as the basis of these experi- Karamchand Gandhi a lonely coined the phrase – “tryst with destiny”– ments. Gandhi’s purpose in writing the man in August 1947. that has become part of India’s national book was, he wrote, “to serve my country, lexicon, and India erupted in jubilation, to fi nd out the Truth and to follow it”. -

Mapping Free Indian Migration to Natal Through a Biographical Lens, 1880-1930

Mapping free Indian migration to Natal Mapping free Indian migration to Natal through a biographical lens, 1880-1930 Kalpana Hiralal Department of History Howard College, University of KwaZulu-Natal [email protected] Abstract The history of indentured Indians has been well documented in South African historiography in terms of migration and settlement. Shipping lists, which meticulously recorded the biographical details of each labourer, together with Indian immigrant reports, provide a wealth of information on the early migratory and labour experiences of indentured Indians. Regrettably, similar documentation regarding passenger or free Indian migration to Natal is absent in the South African archival records. This article adopts a biographical approach as a methodological tool to map the identification practices involved in the migration of passenger or free Indian immigrants to Natal between 1880 and 1930. Both the colonial and Union governments sought to regulate the entry of these immigrants through a system of identity documents. Passage tickets, domicile certificates, affidavits, Certificates of Identity and passports not only facilitated and hindered both individual and family migration, but also show how citizenship was defined, and migration controls were instituted and administered to free immigrants. Thus, as British subjects, free Indian immigrants were not really free but had to constantly, defend and reclaim their civic rights, and attest and verify their identity as the colonial and later the Union government sought new and creative ways to restrict and prohibit their entry. This article illustrates the usefulness of a biographical approach to migration studies, in not only highlighting individual but collective immigrant experiences, which provide a way of capturing the diversity, complexity and the transformational nature of free Indian migration to Natal. -

FROM GANDHI to MAHATMA: JOURNEY of an EXTRAORDINARY JOURNALIST by Dr

Article-4 Global Media Journal – Indian Edition Sponsored by the University of Calcutta www.caluniv.ac.in ISSN 2249 – 5835 Winter Issue/December 2018 Volume: 9/ Number: 2 FROM GANDHI TO MAHATMA: JOURNEY OF AN EXTRAORDINARY JOURNALIST By Dr. Jhumur Ghosh Associate Professor Future Institute of Engineering and Management, Kolkata Email: [email protected] Abstract: When M. K. Gandhi landed in South Africa he was an ordinary man. In South Africa he decided to provide a helping hand to the migrant Indians who were exploited by the white administration. And his initiative was propelled by the newspaper he started off for the process. Such was the power of his communication that the British-owned papers in India like Times of India and the Statesman were forced to comment on the humilities of the Indians in South Africa. He returned to his native land and continued to publish newspapers with the objectives of political campaigning and social awakening. His newspapers are important for understanding his persona and his goals. And they are his gateway to the significant journey from M. K. Gandhi to Mahatma (or the great soul). This greatness traversed the reporting, editing, management of the newspapers he was associated with and left an indelible mark in the minds of all. Key Words: Journalism, Indian Opinion, Young India, Navjivan, Harijan, Gandhiji’s journalistic writing. There has been a lot of discussion on the political leadership and guidance of M. K. Gandhi. His influence in the field of journalism is widespread too and is a lesson to journalism professionals like editors and reporters as well as to those who manage and control newspapers or any other media for that matter. -

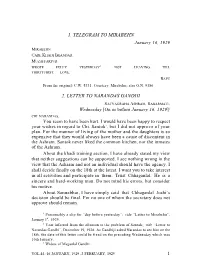

1. Telegram to Mirabehn 2. Letter to Narandas Gandhi

1. TELEGRAM TO MIRABEHN January 16, 1929 MIRABEHN CARE KHADI BHANDAR MUZAFFARPUR WROTE FULLY YESTERDAY1. NOT LEAVING TILL THIRTYFIRST. LOVE. BAPU From the original: C.W. 5331. Courtesy: Mirabehn; also G.N. 9386 2. LETTER TO NARANDAS GANDHI SATYAGRAHA ASHRAM, SABARMATI, Wednesday [On or before January 16, 1929]2 CHI. NARANDAS, You seem to have been hurt. I would have been happy to respect your wishes in regard to Chi. Santok3, but I did not approve of your plan. For the manner of living of the mother and the daughters is so expensive that they would always have been a cause of discontent in the Ashram. Santok never liked the common kitchen, nor the inmates of the Ashram. About the khadi training section, I have already stated my view that neither suggestions can be supported. I see nothing wrong in the view that the Ashram and not an individual should have the agency. I shall decide finally on the 18th at the latest. I want you to take interest in all activities and participate in them. Trust Chhaganlal. He is a sincere and hard-working man. Do not mind his errors, but consider his motive. About Sannabhai, I have simply said that Chhaganlal Joshi’s decision should be final. For no one of whom the secretary does not approve should remain. 1 Presumably a slip for “day before yesterday”; vide “Letter to Mirabehn”, January 14, 1929. 2 Year inferred from the allusion to the problem of Santok; vide “Letter to Narandas Gandhi”, December 19, 1928. As Gandhiji asked Narandas to see him on the 18th, the date of this letter could be fixed on the preceding Wednesday which was 16th January. -

The Influence of Indians in the South African Communist Party, 1934-1952

Being an Indian Communist the South African Way: The Influence of Indians in the South African Communist Party, 1934-1952 Parvathi Raman School of Oriental and African Studies University of London PhD Thesis August 2002 1 ProQuest Number: 10731369 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731369 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Indians that settled in South Africa were differentiated by class, caste, religion, language and region of origin. Whilst some Indians were imported as indentured labourers to work on the sugar plantations in Natal, others came as merchants and traders and set up businesses in South Africa. In this thesis, I consider the historical background to the construction of Tndianness’ in South Africa, where the idea of ‘community’, a contested and transformative concept, called upon existing cultural traditions brought from India, as well as new ways of life that developed in South Africa. Crucially, central to the construction of Tndianness’ were notions of citizenship and belonging within their new environment.