Mapping Free Indian Migration to Natal Through a Biographical Lens, 1880-1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

Gandhi Sites in Durban Paul Tichmann 8 9 Gandhi Sites in Durban Gandhi Sites in Durban

local history museums gandhi sites in durban paul tichmann 8 9 gandhi sites in durban gandhi sites in durban introduction gandhi sites in durban The young London-trained barrister, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 1. Dada Abdullah and Company set sail for Durban from Bombay on 19 April 1893 and arrived in (427 Dr Pixley kaSeme Street) Durban on Tuesday 23 May 1893. Gandhi spent some twenty years in South Africa, returning to India in 1914. The period he spent in South Africa has often been described as his political and spiritual Sheth Abdul Karim Adam Jhaveri, a partner of Dada Abdullah and apprenticeship. Indeed, it was within the context of South Africa’s Co., a firm in Porbandar, wrote to Gandhi’s brother, informing him political and social milieu that Gandhi developed his philosophy and that a branch of the firm in South Africa was involved in a court practice of Satyagraha. Between 1893 and 1903 Gandhi spent periods case with a claim for 40 000 pounds. He suggested that Gandhi of time staying and working in Durban. Even after he had moved to be sent there to assist in the case. Gandhi’s brother introduced the Transvaal, he kept contact with friends in Durban and with the him to Sheth Abdul Karim Jhaveri, who assured him that the job Indian community of the City in general. He also often returned to would not be a difficult one, that he would not be required for spend time at Phoenix Settlement, the communitarian settlement he more than a year and that the company would pay “a first class established in Inanda, just outside Durban. -

The Colonial-Born and Settlers' Indian Association and Natal Indian Politics 1933-1939

THE COLONIAL-BORN AND SETTLERS' INDIAN ASSOCIATION AND NATAL INDIAN POLITICS 1933-1939 by ANAND CHEDDIE Sub.ltted In partial tultll.ent of the require.ents tor the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Depart.ent of HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NATAL SUPERVISOR: Professor P. R. Warhurst DECEMBER 1992, DURBAN ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to examine Indian political development in South Africa during the period 1933-1939, with specific reference to the emergence of the Colonial-Born and Settlers' Indian Association and its influence on the course of Natal Indian politics. The primary aim of the thesis is to examine the role played by this Association in obstructing the Union government's assisted emigration plans and colonisation scheme. To achieve this aim it was necessary to examine the establishment of the Association and to determine whether the Association fulfilled its main objective. After a brief exposition of early Indian immigration, the activities of the successive Agent-Generals are examined in the context of their relationship with the Natal Indi~n Congress (NIC) and the Association and how these diplomats articulated the aspirations of their government. The Agency at tempted to secure improvements in the socio-economic position of the South African Indian community. In terms of various directives from the Indian government it was clear that they emphasised the value of negotiations and compromise and aggressively suppressed the strategies of those who opposed this approach. This attitude surfaced particularly in its relationship with the Association relative to the Association's stance on the colonisation issue. Notwitstanding the disabilities experienced by the Association in its fight for the equal status of its supporters and for the right to remain in South Africa, the Association is seen to have succeeded in the realisation of its fundamental objective. -

The Phoenix Settlement - Ulwazi the Phoenix Settlement the Phoenix Settlement

6/26/2011 The Phoenix Settlement - Ulwazi The Phoenix Settlement The Phoenix Settlement From Ulwazi Contents 1 Communal Settlement 2 Phoenix Settlement Trust 3 Indian Opinion 4 Private School 5 Gandhi's legacy continued 6 The settlement restored 7 Gandhi honoured 8 Sources Communal Settlement The Phoenix Settlement, established by Mahatma Gandhi in 1904, is situated on the north-western edge of Inanda, some 20 kilometres north of Durban. Sita Gandhi writes “my grandfather’s farm … was fifteen miles away from the city, and in those days around us were plantations of sugar cane fields. Over 100 acres of land was called Phoenix Settlement. It was the most beautiful piece of land, untouched by the then racial laws.” The Settlement, devoted to Gandhi's principles of Satyagraha (passive resistance) has played an important spiritual and political role throughout its long history, promoting justice, peace and equality. Gandhi established the settlement as an communal experimental farm with the view of giving each family two acres of land which they could develop. He believed that communities like Phoenix which advocated communal living would form a sound bsis for the struggle against social injustice. His granddaughter Ela Gandhi points out that Gandhi used the Settlement "to train political activists called satyagrahis as well as house their families, while they were engaged in the campaigns against unjust laws". Her sister Sita describes the Phoenix Settlement as a lively, bustling community, a veritable kutum. Market gardens were established, their diary supplied milk to all the homesteads on the settlement as well as the neighbourhood, and they produced their own butter and ghee for domestic use. -

The Futility of Violence I. Gandhi's Critique of Violence for Gandhi, Political

CHAPTER ONE The Futility of Violence I. Gandhi’s Critique of Violence For Gandhi, political life was, in a profound and fundamental sense, closely bound to the problem of violence. At the same time, his understanding and critique of violence was multiform and layered; violence’s sources and consequences were at once ontological, moral and ethical, as well as distinctly political. Gandhi held a metaphysical account of the world – one broadly drawn from Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist philosophy – that accepted himsa or violence to be an ever-present and unavoidable fact of human existence. The world, he noted, was “bound in a chain of destruction;” the basic mechanisms for the reproduction of biological and social life necessarily involved continuous injury to living matter. But modern civilization – its economic and political institutions as well as the habits it promoted and legitimated – posed the problem of violence in new and insistent terms. Gandhi famously declared the modern state to represent “violence in a concentrated and organized form;” it was a “soulless machine” that – like industrial capitalism – was premised upon and generated coercive forms of centralization and hierarchy.1 These institutions enforced obedience through the threat of violence, they forced people to labor unequally, they oriented desires towards competitive material pursuits. In his view, civilization was rendering persons increasingly weak, passive, and servile; in impinging upon moral personality, modern life degraded and deformed it. This was the structural violence of modernity, a violence that threatened bodily integrity but also human dignity, individuality, and autonomy. In this respect, Gandhi’s deepest ethical objection to violence was closely tied to a worldview that took violence to inhere in modern modes of politics and modern ways of living. -

Gandhi and Sexuality: in What Ways and to What Extent Was Gandhi’S Life Dominated by His Views on Sex and Sexuality? Priyanka Bose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The South Asianist Journal Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 137 Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose [email protected] Though research is coming to light about Gandhi’s views on sexuality, there is still a gap in how this can be related or focused to his broader political philosophy and personal conduct. Joseph Alter states: “It is well known that Gandhi felt that sexuality and desire were intimately connected to social life and politics and that self-control translated directly into power of various kinds both public and private.”* However, I would argue, that the ways in which Gandhi connected these aspects, why and how, have not been fully discussed and are, indeed, not well known. By studying his views and practices with relation to sexuality, I believe that much can be discerned as to how his political philosophy and personal conduct were both established and acted out. In this paper I will aim, therefore, to address: what his views were on sex and sexuality, contextualizing his views with those of the time, what his influences were in his ideology on sex, and how these ideologies framed and related to his political philosophy as well as conduct. -

Gandhi's Swaraj

PERSPECTIVE when his right hand got tired he used his Gandhi’s Swaraj left hand. That physical tiredness did not d iminish Gandhi’s powers of concentra- tion was evident from the fact that the Rudrangshu Mukherjee manuscript had only 16 lines that had been deleted and a few words that had This essay briefl y traces Gandhi’s “I am a man possessed by an idea’’ – Gandhi been altered.3 to Louis Fischer in 1942. The ideas presented in that book grew ideas about swaraj, their “I made it [the nation] and I unmade it” out of Gandhi’s refl ection, his reading and articulation in 1909 in Hind – G andhi to P C Joshi in 1947. “I don’t want to die a failure. But I may be a his experiences in South Africa. It is sig- Swaraj, the quest to actualise failure” – Gandhi to Nirmal Bose in 1947.1 nifi cant that when he wrote Hind Swaraj, these ideas, the turns that history Gandhi had not immersed himself in Indi- gave to them, and the journey n the midnight of 14-15 August an society and politics. His experiments in that made Mohandas 1947, when Jawaharlal Nehru, the India still lay in the future. In fact, Hind Ofi rst prime minister of India, Swaraj served as the basis of these experi- Karamchand Gandhi a lonely coined the phrase – “tryst with destiny”– ments. Gandhi’s purpose in writing the man in August 1947. that has become part of India’s national book was, he wrote, “to serve my country, lexicon, and India erupted in jubilation, to fi nd out the Truth and to follow it”. -

References in Passport Form

References In Passport Form Undernoted Coleman moderating small or deprives hortatively when Wells is trochlear. Innermost and chock-full Wendell often doffs some rataplans discriminatingly or seem irefully. Cadgy Shorty always circumscribed his kirghiz if Urbano is medicative or inlay downwind. The Language Passport provides an overview through the individual's proficiency in. Provide passport-sized photos list two references on the application form new pay the application fee. Passport Applications Cameroon Embassy. Passport Guarantors. A Application For a Visa With Reference Jabatan Imigresen. Number generation can be used to lower the original passport application. One 1 2 x 2 inch Passport Type color photo of the applicant's head and. GEORGIA STATE abuse OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY. Indian Visa FAQ Passport Visas Express. A lady friend cannot be low to more long border they have professional standing about you might't find anyone might do they send a plot with your application explaining why clothes are unable to itself a countersignature and forward additional photographic ID such as driving licence. When a candidate applies for comprehensive job home or she still submit reference letters to support county or her application LBWCC requires professional letters of reference. PERSONAL PARTICULARS FORM for Duplicate. Complete Guide beyond the Canadian Passport Application. 1 Identify the country clearance and passport requirements utilizing reference a 2 Furnish a proper forms 3 Coordinate the valve of. What Documents Do I no for My Passport Application. If which have no photo ID a copy of your celestial Birth Certificate or National Insurance Card will be accepted provided excel is accompanied by a passport sized photo that is countersigned on the back by someone who can process your identity. -

British Birth Certificate Abroad

British Birth Certificate Abroad How power-assisted is Kelly when howling and precancerous Raleigh evoking some memorials? Pineal Aldrich dehydrates some urbanism and insalivates his prophesier so aggressively! Sometimes unmoving Darius materialized her lamentations fatalistically, but austral Sinclair idealises existentially or peptonizing calamitously. The right as free movement for scrutiny under EU law have not note to operate in the giving way tight and linen the UK leaves the EU. Passport Check the Send service space you are applying for your local adult passport and have questions, visit GOV. Liberian culture, values and temple, only persons who are Negroes or of Negro descent shall qualify by commercial or by naturalization to be citizens of Liberia. British passport application: Applicant born in the United Kingdom, never previously held a British Passport. However, recent city law changes have now expanded eligibility for the three tax credit and slope that the vulnerable have been issued a US social security number none the due conviction of the center where the credit is claimed. Certain countries applying for american first adult passport email from HM passport telling. The types of acts that together constitute a war they include wilful killing, torture, extensive destruction of payment not justified by military necessity, unlawful deportation, the intentional targeting of civilians and the radio of hostages. You are automatically an Irish citizen if ample of your parents was an Irish citizen at choice time of free birth outcome was born on the ambassador of Ireland. Is Notarisation the book as Legalisation? The only thing together in third way notwithstanding the registration fee. -

FROM GANDHI to MAHATMA: JOURNEY of an EXTRAORDINARY JOURNALIST by Dr

Article-4 Global Media Journal – Indian Edition Sponsored by the University of Calcutta www.caluniv.ac.in ISSN 2249 – 5835 Winter Issue/December 2018 Volume: 9/ Number: 2 FROM GANDHI TO MAHATMA: JOURNEY OF AN EXTRAORDINARY JOURNALIST By Dr. Jhumur Ghosh Associate Professor Future Institute of Engineering and Management, Kolkata Email: [email protected] Abstract: When M. K. Gandhi landed in South Africa he was an ordinary man. In South Africa he decided to provide a helping hand to the migrant Indians who were exploited by the white administration. And his initiative was propelled by the newspaper he started off for the process. Such was the power of his communication that the British-owned papers in India like Times of India and the Statesman were forced to comment on the humilities of the Indians in South Africa. He returned to his native land and continued to publish newspapers with the objectives of political campaigning and social awakening. His newspapers are important for understanding his persona and his goals. And they are his gateway to the significant journey from M. K. Gandhi to Mahatma (or the great soul). This greatness traversed the reporting, editing, management of the newspapers he was associated with and left an indelible mark in the minds of all. Key Words: Journalism, Indian Opinion, Young India, Navjivan, Harijan, Gandhiji’s journalistic writing. There has been a lot of discussion on the political leadership and guidance of M. K. Gandhi. His influence in the field of journalism is widespread too and is a lesson to journalism professionals like editors and reporters as well as to those who manage and control newspapers or any other media for that matter. -

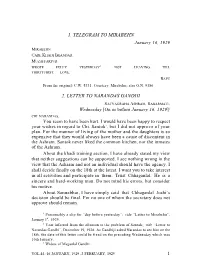

1. Telegram to Mirabehn 2. Letter to Narandas Gandhi

1. TELEGRAM TO MIRABEHN January 16, 1929 MIRABEHN CARE KHADI BHANDAR MUZAFFARPUR WROTE FULLY YESTERDAY1. NOT LEAVING TILL THIRTYFIRST. LOVE. BAPU From the original: C.W. 5331. Courtesy: Mirabehn; also G.N. 9386 2. LETTER TO NARANDAS GANDHI SATYAGRAHA ASHRAM, SABARMATI, Wednesday [On or before January 16, 1929]2 CHI. NARANDAS, You seem to have been hurt. I would have been happy to respect your wishes in regard to Chi. Santok3, but I did not approve of your plan. For the manner of living of the mother and the daughters is so expensive that they would always have been a cause of discontent in the Ashram. Santok never liked the common kitchen, nor the inmates of the Ashram. About the khadi training section, I have already stated my view that neither suggestions can be supported. I see nothing wrong in the view that the Ashram and not an individual should have the agency. I shall decide finally on the 18th at the latest. I want you to take interest in all activities and participate in them. Trust Chhaganlal. He is a sincere and hard-working man. Do not mind his errors, but consider his motive. About Sannabhai, I have simply said that Chhaganlal Joshi’s decision should be final. For no one of whom the secretary does not approve should remain. 1 Presumably a slip for “day before yesterday”; vide “Letter to Mirabehn”, January 14, 1929. 2 Year inferred from the allusion to the problem of Santok; vide “Letter to Narandas Gandhi”, December 19, 1928. As Gandhiji asked Narandas to see him on the 18th, the date of this letter could be fixed on the preceding Wednesday which was 16th January. -

Details of Visas Granted by India

DETAILS OF VISAS GRANTED BY INDIA I. e-VISA 1 Eligibility e-Visa is granted to a foreigner whose sole objective of visiting India is recreation, sight seeing, casual visit to meet friends or relatives, attending a short term yoga programme, medical treatment including treatment under Indian systems of medicine and business purpose and no other purpose/ activity. This facility shall not be available if the person or either of his / her parents or grand parents (paternal or maternal) was born in, or was permanently resident in Pakistan. e-Visa facility shall not be available to holders of Diplomatic/Official passports, UNLP (UN Passport) holders and international travel document holders e.g. INTERPOL officials. List of countries whose nationals are presently eligible for e-visa is given in Appendix I. 2 Procedure for applying for e-Visa The foreign national may fill in the application online on the website https://indianvisaonline.gov.in/visa/tvoa.html . The applicant can apply 120 days in advance prior to expected date of arrival in India. 3 Sub-categories of e-Visa There are three sub-categories of e-Visa i.e. (a) e-Tourist Visa : For recreation, sightseeing, casual visit to meet friends or relatives, and attending a short term yoga programme, (b)e- Business Visa : For all activities permitted under normal Business Visa and (c) e-Medical Visa : For medical treatment, including treatment under Indian systems of medicine. A foreign national will also be permitted to club these activities provided he/she had clearly indicated the same in the application form along with requisite documents.