ECONOMIC and SOCIAL STRUCTURES in EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY MANILA: /Rv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines

Title: Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines Teacher: Anne Sharkey, Huntley High School Summary: This lesson took part as a comparison of the different aspects of the Spanish maritime empires with a comparison of Spanish colonization of Mexico & Cuba to that of the Philippines. The lessons in this unit begin with a basic understanding of each land based empire of the time period 1450-1750 (Russia, Ottomans, China) and then with a movement to the maritime transoceanic empires (Spain, Portugal, France, Britain). This lesson will come after the students already have been introduced to the Spanish colonial empire and the Spanish trade systems through the Atlantic and Pacific. Through this lesson the students will gain an understanding of Spanish systems of colonial rule and control of the peoples and the territories. The evaluation of causes of actions of the Spanish, reactions to native populations, and consequences of Spanish involvement will be discussed with the direct correlation between the social systems and structures created, the influence of the Christian missionaries, the rebellions and conflicts with native populations between the two locations in the Latin American Spanish colonies and the Philippines. Level: High School Content Area: AP World History, World History, Global Studies Duration: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Compare the economic, political, social, and cultural structures of the Spanish involvement in Latin America with the Spanish involvement with the Philippines Compare the effects of mercantilism on Latin America and the Philippines Evaluate the role of the encomienda and hacienda system on both regions Evaluate the influence of the silver trade on the economies of both regions Analyze the creation of a colonial society through the development of social classes—Peninsulares, creoles, mestizos, mulattos, etc. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

Independence and Turmoil

PART INDEPENDENCE I AND TURMOIL Clayton-New History Of Modern Latin America.indd 1 07/04/17 10:00 PM 2 Independence and Turmoil Latin America passed through one of its most important historical eras in the first half of the nineteenth century. In a tumultuous twenty-year span, from about 1806 to 1826, almost all of the Spanish and Portuguese colonies broke off from their colonizers and became independent nations. The path that each nation followed to independence was often complicated and marked by fits and starts, periods of intense political confusion, sharp military conflicts, inter- ludes of peace, more battles, and by ethnic and political divisions within the revolutionary movements that defy easy or clear analysis. In the largest context, the Wars of Independence marked a continuation of the same forces that drove the American, French, and Haitian revolutions of the late eighteenth century, all lumped together into something known as the Age of Democratic Revolutions. In the simplest terms, the old forms of govern- ment and rule, largely monarchies across the Western World, were overthrown for republican forms of government. But, as in America, France, and Haiti, the seemingly simple becomes more complex as one probes beneath the surface of these wars in Latin America. For example, while most of the new nations overthrew the king and replaced political authority with a republic, Brazil did not. It replaced a monarch with another monarch and glided into the nineteenth century without the cataclys- mic battles and campaigns that characterized the wars in the Spanish colonies. Other forces at work in the Spanish colonies, especially economic and com- mercial ones, argued for separating from the crown and getting rid of the monopolies and restrictions long set in place by the monarchy to regulate the colonies. -

Spain's Empire in the Americas

ahon11_sena_ch02_S2_s.fm Page 44 Friday, October 2, 2009 10:41 AM ahon09_sena_ch02_S2_s.fm Page 45 Friday, October 26, 2007 2:01 PM Section 2 About a year later, Cortés returned with a larger force, recaptured Step-by-Step Instruction Tenochtitlán, and then destroyed it. In its place he built Mexico City, The Indians Fear Us the capital of the Spanish colony of New Spain. Cortés used the same methods to subdue the Aztecs in Mexico SECTION SECTION The Indians of the coast, because of some fears “ that another conquistador, Francisco Pizarro, used in South America. of us, have abandoned all the country, so that for Review and Preview 2 Pizarro landed on the coast of Peru in 1531 to search for the Incas, thirty leagues not a man of them has halted. ” who were said to have much gold. In September 1532, he led about Students have learned about new 170 soldiers through the jungle into the heart of the Inca Empire. contacts between peoples of the Eastern —Hernando de Soto, Spanish explorer and conqueror, report on Pizarro then took the Inca ruler Atahualpa (ah tuh WAHL puh) pris- and Western hemispheres during the expedition to Florida, 1539 oner. Although the Inca people paid a huge ransom to free their ruler, Age of Exploration. Now students will Pizarro executed him anyway. By November 1533, the Spanish had focus on Spain’s early success at estab- defeated the leaderless Incas and captured their capital city of Cuzco. lishing colonies in the Americas. Why the Spanish Were Victorious How could a few � Hernando de Soto hundred Spanish soldiers defeat Native American armies many Vocabulary Builder times their size? Several factors explain the Spaniards’ success. -

Great Work Everyone! I Am Very Proud of Our Final Products!

GREAT WORK EVERYONE! I AM VERY PROUD OF OUR FINAL PRODUCTS! Why did the Creoles lead the fight for Latin American Independence? Partial Essay- 1st Hour Global HIPPOS Between 1500-1800 CE, the Spanish established colonies across the world including Latin America. With the age of the Enlightenment, inspired by the ideas of Locke (life, liberty, property) and Voltaire (Freedom of speech, religion), people of the lower classes were encouraged to revolt. With the success of the American and Haitian Revolutions, and the courage of the fighting French in the French Revolution, Latin American Creoles were inspired to gain control in the country of their birth. During the early 1800’s, the Creoles (also known as the second class citizens) fought for Latin American Independence from the Spanish. The Creoles wanted to establish control over the Spanish dominated economy, to gain political authority over the peninsulares, and settle social unrest in the region. During this time Spain dominated Latin America’s economy. “We in America are perhaps the first to be forced by our own government to sell our products at artificially low prices and buy what we need at artificially high prices,” (Doc. C). Due to Spain’s mercantilist ideals, the country controlled all aspects of Latin America’s economy in order to benefit the mother country. Spain regulated the colonies goods that were imported and exported, causing the daily detriment of the colonists. In “An Open Letter to America,” Juan Pablo Viscardo, a Creole, encouraged Latin American colonies to acknowledge their economic oppression and revolt against the Spanish. -

Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES

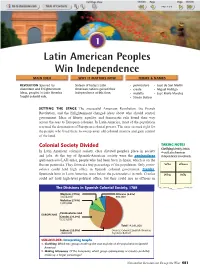

1 Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES REVOLUTION Spurred by Sixteen of today’s Latin • peninsulare •José de San Martín discontent and Enlightenment American nations gained their • creole •Miguel Hidalgo ideas, peoples in Latin America independence at this time. •mulatto •José María Morelos fought colonial rule. • Simón Bolívar SETTING THE STAGE The successful American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Enlightenment changed ideas about who should control government. Ideas of liberty, equality, and democratic rule found their way across the seas to European colonies. In Latin America, most of the population resented the domination of European colonial powers. The time seemed right for the people who lived there to sweep away old colonial masters and gain control of the land. Colonial Society Divided TAKING NOTES Clarifying Identify details In Latin American colonial society, class dictated people’s place in society about Latin American and jobs. At the top of Spanish-American society were the peninsulares independence movements. (peh•neen•soo•LAH•rehs), people who had been born in Spain, which is on the Iberian peninsula. They formed a tiny percentage of the population. Only penin- WhoWh WhereWh sulares could hold high office in Spanish colonial government. Creoles, Spaniards born in Latin America, were below the peninsulares in rank. Creoles When Why could not hold high-level political office, but they could rise as officers in The Divisions in Spanish Colonial Society, 1789 Mestizos (7.3%) Africans (6.4%) 1,034,000 902,000 Mulattos (7.6%) 1,072,000 Peninsulares and EUROPEANS Creoles (22.9%) {3,223,000 Total 14,091,000 Indians (55.8%) Source: Colonial Spanish America, 7,860,000 by Leslie Bethell SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Graphs 1. -

Land of Abundance: a History of Settler Colonialism in Southern California

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Benjamin Shultz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Shultz, Benjamin, "LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA" (2020). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 985. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 LAND OF ABUNDANCE: A HISTORY OF SETTLER COLONIALISM IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Benjamin O Shultz June 2020 Approved by: Thomas Long, Committee Chair, History Teresa Velasquez, Committee Member, Anthropology Michal Kohout, Committee Member, Geography © 2020 Benjamin O Shultz ABSTRACT The historical narrative produced by settler colonialism has significantly impacted relationships among individuals, groups, and institutions. This thesis focuses on the enduring narrative of settler colonialism and its connection to American Civilization. -

Seventeenth-Century Spanish Colonial Identity in New Mexico: a Study of Identity Practices Through Material Culture

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Anthropology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-15-2019 Seventeenth-Century Spanish Colonial Identity in New Mexico: A Study of Identity Practices through Material Culture Caroline M. Gabe University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Chicana/o Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Latin American History Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Gabe, Caroline M.. "Seventeenth-Century Spanish Colonial Identity in New Mexico: A Study of Identity Practices through Material Culture." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/184 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Caroline Marie Gabe Candidate Anthropology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Emily Lena Jones , Co-Chairperson Dr. Frances Hayashida , Co-Chairperson Dr. Bruce B. Huckell Prof. Christopher Wilson i SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH COLONIAL IDENTITY IN NEW MEXICO: A STUDY -

A Short History of the United States

A Short History of the United States Robert V. Remini For Joan, Who has brought nothing but joy to my life Contents 1 Discovery and Settlement of the New World 1 2 Inde pendence and Nation Building 31 3 An Emerging Identity 63 4 The Jacksonian Era 95 5 The Dispute over Slavery, Secession, and the Civil War 127 6 Reconstruction and the Gilded Age 155 7 Manifest Destiny, Progressivism, War, and the Roaring Twenties 187 Photographic Insert 8 The Great Depression, the New Deal, and World War II 215 9 The Cold War and Civil Rights 245 10 Violence, Scandal, and the End of the Cold War 277 11 The Conservative Revolution 305 Reading List 337 Index 343 About the Author Other Books by Robert V. Remini Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher 1 Discovery and Settlement of the New World here are many intriguing mysteries surrounding the peo- T pling and discovery of the western hemisphere. Who were the people to first inhabit the northern and southern continents? Why did they come? How did they get here? How long was their migration? A possible narrative suggests that the movement of ancient people to the New World began when they crossed a land bridge that once existed between what we today call Siberia and Alaska, a bridge that later dis- appeared because of glacial melting and is now covered by water and known as the Bering Strait. It is also possible that these early people were motivated by wanderlust or the need for a new source of food. Perhaps they were searching for a better climate, and maybe they came for religious reasons, to escape persecution or find a more congenial area to practice their partic u lar beliefs. -

Los Españoles De América: Criollos, Indígenas Y Castas

08-JosemariaAguileraManzano.qxp:Maquetación 1 3/12/08 19:32 Página 167 LOS ESPAÑOLES DE AMÉRICA: CRIOLLOS, INDÍGENAS Y CASTAS José María Aguilera Manzano Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas 08-JosemariaAguileraManzano.qxp:Maquetación 1 3/12/08 19:32 Página 168 08-JosemariaAguileraManzano.qxp:Maquetación 1 3/12/08 19:32 Página 169 Los años de 1808 a 1810 fueron decisivos para América Latina. La llegada de las tropas de Napoleón Bona- parte a la Península Ibérica privó a las colonias del Nuevo Mundo de su metrópoli y dejó un vació de poder que pugnaron por llenar intereses rivales. Esta crisis desembocó en la independencia y fragmentación en re- públicas de casi todo el antiguo territorio americano del Imperio español. Sólo permanecieron bajo su control las islas de Cuba y Puerto Rico, en el Caribe, y las Filipinas, en Asia. Sin embargo, esta crisis política tenía una larga prehistoria que hay que situar en el siglo XVIII, periodo durante el cual crecieron las economías coloniales, se desarrollaron las sociedades y avanzaron considerablemente las ideas. En la segunda mitad de ese siglo, América se vio sometida a un doble proceso: la repercusión de la nueva política imperial y la pre- sión de las cambiantes condiciones coloniales. La nueva política se tradujo en una serie de transformaciones comerciales, institucionales y militares, conocidas como las “Reformas Borbónicas”. Con ellas se pretendía acrecentar los ingresos por parte de las cajas reales y concentrar los puestos de poder en manos de penin- sulares. Las condiciones cambiantes consistieron en el crecimiento de la población, la expansión de la minería y de la agricultura y el desarrollo del mercado interno del Nuevo Mundo. -

Florida Historical Quarterly

COVER Looking north along Hollywood Beach in March 1935. This photograph was taken for the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce for a publicity brochure. It was reproduced as a postcard in 1939. The postcard is in the collection of the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida, Gaines- ville. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Volume LXII, Number 3 January 1984 COPYRIGHT 1984 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. Second class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. Printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. (ISSN 0015-4113) THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Jeffry Charbonnet, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Herbert J. Doherty, Jr. University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) J. Leitch Wright, Jr. Florida State University Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, originality of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and interest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. Footnotes are to be numbered consecutively in the text and assembled at the end of the article. Particular attention should be given to following the footnote style of the Quarterly. The author should submit an original and retain a carbon for security. The Florida Historical Society and the Editor of the Florida Historical Quarterly accept no responsibility for state- ments made or opinions held by authors. -

Silleras-Fernandez CV Jan. 21

Núria Silleras–Fernández Department of Spanish & Portuguese University of Colorado Boulder 278 UCB Boulder, CO 80309–0278 [email protected] Phone: 303–492–5864 Fax: 303–492–3699 Academia.edu ORCID ID: 0000-0002-1762-1407 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC POSITIONS: Associate Professor, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Colorado Boulder, Since 2016. Affiliated Faculty in History and Women and Gender Studies, Since 2016. Board Member of the CU Mediterranean Studies Group (since 2016, and member since 2011). Assistant Professor, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Colorado Boulder, 2009–16. Lecturer of Spanish Literature, Literature Department, University of California Santa Cruz, September 2006–9. Lecturer of European History, History Department, University of California Santa Cruz, March 2005–9. Adjunct Professor of Medieval History, Department of Ancient and Medieval Studies, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain), 1998–2000. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Book Review Editor: Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, The Medieval Academy of America, 2020–3. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION: Postdoctoral/Residential Research Fellow: The Emergence of “the West”: Shifting Hegemonies in the Medieval Mediterranean,” University of California Humanities Research Institute (Irvine,