Silleras-Fernandez CV Jan. 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 X 10.Three Lines .P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51530-6 - Rhetoric beyond Words: Delight and Persuasion in the Arts of the Middle Ages Edited by Mary Carruthers Index More information Index Abelard, Peter 133, 160, 174, 250–1, 275 and ductus 215, 216, 228, 239–43 Commentaria in Epistolam Pauli ad and memory 215–16, 231, 233, 239–43 Romanos 252–4 and scholasticism 20–8 Commentary on Boethius’ De differentiis arrangement (dispositio) in 36–8, 229–30 topicis 202, 251 as concept in rhetorical discourse 4, 26, 27, Easter liturgy for Paraclete 256–63 32, 190–1 Letter 5 257–8 borrows rhetorical vocabulary 4, 7, 36–7 on rhetoric 202, 251–63 compared to poetry 26, 190–1 accent see inflection Aristotle 24–5, 131 Accursius (Bolognese jurist) 125 influence of Physics and Metaphysics Ackerman, James S. 40 21–2, 24–5 acting 161–3, 166–7 on epistēmē, téchnē and empeiría 1–2 compared to oratory 10, 127, 157–8 on ethos, logos and pathos 7 masks and 158–9 Rhetoric 2, 7, 36, 127, 128 actio see delivery theory of causality 21–2, 24–5 Adam of Dryburgh (Adam Scot), De tripartite Topics 202 tabernaculo 233, 242 Arnulf of St Ghislain 65 Aelred of Rievaulx (abbot) 124, 133–5 arrangement (dispositio) De spiritali amicitia 134 and ductus 196, 199–206, 229–30, 263 agency as mapping 191–2 of audiences 2, 165–6 Geoffrey of Vinsauf on 190–2 of ductus 199–206 in architecture 36–8, 229–30 of roads 191 personified as ‘Deduccion’ 205–6 of the work itself 201–2 Quintilian on 4, 230 shared by composer and performer 88 see also consilium; ductus; maps, mapping; Agrippa (Roman emperor) 281–3 -

Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines

Title: Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines Teacher: Anne Sharkey, Huntley High School Summary: This lesson took part as a comparison of the different aspects of the Spanish maritime empires with a comparison of Spanish colonization of Mexico & Cuba to that of the Philippines. The lessons in this unit begin with a basic understanding of each land based empire of the time period 1450-1750 (Russia, Ottomans, China) and then with a movement to the maritime transoceanic empires (Spain, Portugal, France, Britain). This lesson will come after the students already have been introduced to the Spanish colonial empire and the Spanish trade systems through the Atlantic and Pacific. Through this lesson the students will gain an understanding of Spanish systems of colonial rule and control of the peoples and the territories. The evaluation of causes of actions of the Spanish, reactions to native populations, and consequences of Spanish involvement will be discussed with the direct correlation between the social systems and structures created, the influence of the Christian missionaries, the rebellions and conflicts with native populations between the two locations in the Latin American Spanish colonies and the Philippines. Level: High School Content Area: AP World History, World History, Global Studies Duration: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Compare the economic, political, social, and cultural structures of the Spanish involvement in Latin America with the Spanish involvement with the Philippines Compare the effects of mercantilism on Latin America and the Philippines Evaluate the role of the encomienda and hacienda system on both regions Evaluate the influence of the silver trade on the economies of both regions Analyze the creation of a colonial society through the development of social classes—Peninsulares, creoles, mestizos, mulattos, etc. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

Independence and Turmoil

PART INDEPENDENCE I AND TURMOIL Clayton-New History Of Modern Latin America.indd 1 07/04/17 10:00 PM 2 Independence and Turmoil Latin America passed through one of its most important historical eras in the first half of the nineteenth century. In a tumultuous twenty-year span, from about 1806 to 1826, almost all of the Spanish and Portuguese colonies broke off from their colonizers and became independent nations. The path that each nation followed to independence was often complicated and marked by fits and starts, periods of intense political confusion, sharp military conflicts, inter- ludes of peace, more battles, and by ethnic and political divisions within the revolutionary movements that defy easy or clear analysis. In the largest context, the Wars of Independence marked a continuation of the same forces that drove the American, French, and Haitian revolutions of the late eighteenth century, all lumped together into something known as the Age of Democratic Revolutions. In the simplest terms, the old forms of govern- ment and rule, largely monarchies across the Western World, were overthrown for republican forms of government. But, as in America, France, and Haiti, the seemingly simple becomes more complex as one probes beneath the surface of these wars in Latin America. For example, while most of the new nations overthrew the king and replaced political authority with a republic, Brazil did not. It replaced a monarch with another monarch and glided into the nineteenth century without the cataclys- mic battles and campaigns that characterized the wars in the Spanish colonies. Other forces at work in the Spanish colonies, especially economic and com- mercial ones, argued for separating from the crown and getting rid of the monopolies and restrictions long set in place by the monarchy to regulate the colonies. -

Spain's Empire in the Americas

ahon11_sena_ch02_S2_s.fm Page 44 Friday, October 2, 2009 10:41 AM ahon09_sena_ch02_S2_s.fm Page 45 Friday, October 26, 2007 2:01 PM Section 2 About a year later, Cortés returned with a larger force, recaptured Step-by-Step Instruction Tenochtitlán, and then destroyed it. In its place he built Mexico City, The Indians Fear Us the capital of the Spanish colony of New Spain. Cortés used the same methods to subdue the Aztecs in Mexico SECTION SECTION The Indians of the coast, because of some fears “ that another conquistador, Francisco Pizarro, used in South America. of us, have abandoned all the country, so that for Review and Preview 2 Pizarro landed on the coast of Peru in 1531 to search for the Incas, thirty leagues not a man of them has halted. ” who were said to have much gold. In September 1532, he led about Students have learned about new 170 soldiers through the jungle into the heart of the Inca Empire. contacts between peoples of the Eastern —Hernando de Soto, Spanish explorer and conqueror, report on Pizarro then took the Inca ruler Atahualpa (ah tuh WAHL puh) pris- and Western hemispheres during the expedition to Florida, 1539 oner. Although the Inca people paid a huge ransom to free their ruler, Age of Exploration. Now students will Pizarro executed him anyway. By November 1533, the Spanish had focus on Spain’s early success at estab- defeated the leaderless Incas and captured their capital city of Cuzco. lishing colonies in the Americas. Why the Spanish Were Victorious How could a few � Hernando de Soto hundred Spanish soldiers defeat Native American armies many Vocabulary Builder times their size? Several factors explain the Spaniards’ success. -

Jorge J. E. Gracia

. Jorge J. E. Gracia PERSONAL INFORMATION Father: Dr. Ignacio J. L. de la C. Gracia Dubié Mother: Leonila M. Otero Muñoz Married to Norma E. Silva Casabé in 1966 Daughters: Leticia Isabel and Clarisa Raquel Grandchildren: James M. Griffin, Clarisa E. Griffin, Sofia G. Taberski, and Eva L. Taberski Office Addresses: Department of Philosophy, University at Buffalo 123 Park Hall, Buffalo, NY 14260-4150 Phone: (716) 645-2444; FAX (716) 645-6139 Department of Comparative Literature, University at Buffalo 631 Clemens Hall, Buffalo, NY 14260-4610 Phone: (716) 645-2066; FAX (716) 645-5979 Home Address: 420 Berryman Dr. Amherst, NY 14226 Phone: (716) 835-5747 EDUCATION High School Bachiller en Ciencias and Bachiller en Letras, with highest honors, St. Thomas Military Academy, La Habana, 1960 College/University B.A. in Philosophy, with honors, Wheaton College, 1965 M.A. in Philosophy, University of Chicago, 1966 M.S.L. in Philosophy, magna cum laude, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1970 Ph.D. in Medieval Philosophy, University of Toronto, 1971 Other Studies One year of graduate study and research at the Institut d'Estudis Catalans, Barcelona, 1969-70 One year of study at the School of Architecture, Universidad de La Habana, 1960-61 One year of study at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas de San Alejandro, La Habana, 1960-61 Doctoral Dissertation "Francesc Eiximenis's Terç del Crestià: Edition and Study of Sources," Toronto, 1971, 576 pp. Dissertation Committee: J. Gulsoy, A. Maurer, E. Synan AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION IN PHILOSOPHY Systematic: -

Nousletter 2015

Department of Philosophy Noûsletter Number 21 - Summer 2015 No. 21 · Summer 2015 noûsletter Page 2 Table of Contents Peter Hare Outstanding Assistant Awards .............. 45 Letter from the Chair ................................................................... 3 Hare Award for Best Overall Essay .............................. 46 From the Director of Undergraduate Education ........... 7 Hourani Award for Outstanding Essay in Ethics .. 46 Faculty of the Department of Philosophy ......................... 7 Perry Awards for Best Dissertation ............................. 46 In Remembrance ............................................................................ 8 Steinberg Essay Prize Winners ...................................... 46 William Baumer (1932 —2014) ....................................... 8 Whitman Scholarship Winner ........................................ 46 Newton Garver (1928 – 2014) .......................................... 9 Confucian Institute Dissertation Fellowship .......... 46 Anthony Fay (1979-2015) ................................................ 11 The People Who Make It Possible ..................................... 47 Faculty Updates ........................................................................... 12 The Peter Hare Award ........................................................ 47 Introducing Alexandra King ............................................. 12 The Hourani Lectures ......................................................... 47 Introducing Nicolas Bommarito ................................... -

Memory in the Middle Ages: Approaches from Southwestern

CMS MEMORY IN THE MIDDLE AGES APPROACHES FROM SOUTHWESTERN EUROPE Memory was vital to the functioning of the medieval world. People in medieval societies shared an identity based on commonly held memo- MEMORY IN THE MIDDLE AGES THE MIDDLE IN MEMORY ries. Religions, rulers, and even cities and nations justifi ed their exis- tence and their status through stories that guaranteed their deep and unbroken historical roots. The studies in this interdisciplinary collec- tion explore how manifestations of memory can be used by historians as a prism through which to illuminate European medieval thought and value systems.The contributors have drawn a link between memory and medieval science, management of power and remembrance of the dead ancestors through examples from southern Europe as a means and Studies CARMEN Monographs of enriching and complicating our study of the Middle Ages; this is a region with a large amount of documentation but which to date has not been widely studied. Finally, the contributors have researched the role of memory as a means to sustain identity and ideology from the past to the present. This book has two companion volumes, dealing with ideology and identity as part of a larger project that seeks to map and interrogate the signifi cance of all three concepts in the Middle Ages in the West. CARMEN Monographs and Studies seeks to explore the movements of people, ideas, religions and objects in the medieval period. It welcomes publications that deal with the migration of people and artefacts in the Middle Ages, the adoption of Christianity in northern, Baltic, and east- MEMORY IN central Europe, and early Islam and its expansion through the Umayyad caliphate. -

Great Work Everyone! I Am Very Proud of Our Final Products!

GREAT WORK EVERYONE! I AM VERY PROUD OF OUR FINAL PRODUCTS! Why did the Creoles lead the fight for Latin American Independence? Partial Essay- 1st Hour Global HIPPOS Between 1500-1800 CE, the Spanish established colonies across the world including Latin America. With the age of the Enlightenment, inspired by the ideas of Locke (life, liberty, property) and Voltaire (Freedom of speech, religion), people of the lower classes were encouraged to revolt. With the success of the American and Haitian Revolutions, and the courage of the fighting French in the French Revolution, Latin American Creoles were inspired to gain control in the country of their birth. During the early 1800’s, the Creoles (also known as the second class citizens) fought for Latin American Independence from the Spanish. The Creoles wanted to establish control over the Spanish dominated economy, to gain political authority over the peninsulares, and settle social unrest in the region. During this time Spain dominated Latin America’s economy. “We in America are perhaps the first to be forced by our own government to sell our products at artificially low prices and buy what we need at artificially high prices,” (Doc. C). Due to Spain’s mercantilist ideals, the country controlled all aspects of Latin America’s economy in order to benefit the mother country. Spain regulated the colonies goods that were imported and exported, causing the daily detriment of the colonists. In “An Open Letter to America,” Juan Pablo Viscardo, a Creole, encouraged Latin American colonies to acknowledge their economic oppression and revolt against the Spanish. -

Chapter 680 of Francesc Eiximenis's Dotzè Del Crestià David J. Viera

You are accessing the Digital Archive of the Esteu accedint a l'Arxiu Digital del Catalan Catalan Review Journal. Review By accessing and/or using this Digital A l’ accedir i / o utilitzar aquest Arxiu Digital, Archive, you accept and agree to abide by vostè accepta i es compromet a complir els the Terms and Conditions of Use available at termes i condicions d'ús disponibles a http://www.nacs- http://www.nacs- catalanstudies.org/catalan_review.html catalanstudies.org/catalan_review.html Catalan Review is the premier international Catalan Review és la primera revista scholarly journal devoted to all aspects of internacional dedicada a tots els aspectes de la Catalan culture. By Catalan culture is cultura catalana. Per la cultura catalana s'entén understood all manifestations of intellectual totes les manifestacions de la vida intel lectual i and artistic life produced in the Catalan artística produïda en llengua catalana o en les language or in the geographical areas where zones geogràfiques on es parla català. Catalan Catalan is spoken. Catalan Review has been Review es publica des de 1986. in publication since 1986. On the King's Chancellor: Chapter 680 of Francesc Eiximenis's Dotzè del Crestià David J. Viera Catalan Review, Vol. XII, number 2 (1998), p. 89 -97 ON THE KING'S CHANCELLOR: CHAPTER 680 OF FRANCESC EIXIMENIS'S DOTZÈ DEL CRESTIÀ DAVID J. VIERA F rancesc Eiximenis included several chapters in the Dotzè del Crestià (ca. 1386) that correspond to the duties of government officials, from the king to municipallaw enforcement officers. I Chapter 680 begins the section on royal chancellors (ehs. -

Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES

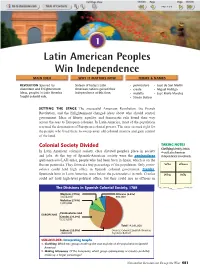

1 Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES REVOLUTION Spurred by Sixteen of today’s Latin • peninsulare •José de San Martín discontent and Enlightenment American nations gained their • creole •Miguel Hidalgo ideas, peoples in Latin America independence at this time. •mulatto •José María Morelos fought colonial rule. • Simón Bolívar SETTING THE STAGE The successful American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Enlightenment changed ideas about who should control government. Ideas of liberty, equality, and democratic rule found their way across the seas to European colonies. In Latin America, most of the population resented the domination of European colonial powers. The time seemed right for the people who lived there to sweep away old colonial masters and gain control of the land. Colonial Society Divided TAKING NOTES Clarifying Identify details In Latin American colonial society, class dictated people’s place in society about Latin American and jobs. At the top of Spanish-American society were the peninsulares independence movements. (peh•neen•soo•LAH•rehs), people who had been born in Spain, which is on the Iberian peninsula. They formed a tiny percentage of the population. Only penin- WhoWh WhereWh sulares could hold high office in Spanish colonial government. Creoles, Spaniards born in Latin America, were below the peninsulares in rank. Creoles When Why could not hold high-level political office, but they could rise as officers in The Divisions in Spanish Colonial Society, 1789 Mestizos (7.3%) Africans (6.4%) 1,034,000 902,000 Mulattos (7.6%) 1,072,000 Peninsulares and EUROPEANS Creoles (22.9%) {3,223,000 Total 14,091,000 Indians (55.8%) Source: Colonial Spanish America, 7,860,000 by Leslie Bethell SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Graphs 1. -

The Jewish Precedent in the Spanish Politics of Conversion of Muslims and Moriscos Isabelle Poutrin

The Jewish Precedent in the Spanish Politics of Conversion of Muslims and Moriscos Isabelle Poutrin To cite this version: Isabelle Poutrin. The Jewish Precedent in the Spanish Politics of Conversion of Muslims and Moriscos. Journal of Levantine Studies, Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, 2016, 6, pp.71 - 87. hal-01470934 HAL Id: hal-01470934 https://hal-upec-upem.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01470934 Submitted on 17 Feb 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Levantine Studies Vol. 6, Summer/Winter 2016, pp. 71-87 The Jewish Precedent in the Spanish Politics of Conversion of Muslims and Moriscos* Isabelle Poutrin Université Paris-Est Membre de l’IUF [email protected] The legal elimination of the Jews and Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula forms a remarkably brief chronological sequence.1 In 1492, just after the conquest of Granada, the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, ordered the expulsion of the Jews of Castile and Aragon.2 In 1496, Manuel I ordered the expulsion of the Jews and Muslims of Portugal.3 Two years later, John of Albret and Catherine of Navarre expelled the Jews from their kingdom.4 In 1502 the Catholic Monarchs decreed the expulsion of the Muslims from the entire Crown of Castile.5 And in 1525 Emperor Charles V expelled the Muslims from the Crown of Aragon, which included the kingdoms of Valencia and Aragon and the Principality of Catalonia.