View / Open Tribit Oregon 0171A 12022.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beatriz Bernal and Her Cristalián De España: A

i CHIVALRY THROUGH A WOMAN’S PEN: BEATRIZ BERNAL AND HER CRISTALIÁN DE ESPAÑA: A TRANSCRIPTION AND STUDY ________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _____________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________________________________________ By Jodi Growitz Shearn August, 2012 Examining Committee Members: Montserrat Piera, Advisory Chair, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Hortensia Morell, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Teresa Scott Soufas, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Stacey Schlau, External Member, Department of Languages and Cultures, West Chester University ii © Copyright 2012 by Jodi Growitz Shearn All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Title: Chivalry through a Woman’s Pen: Beatriz Bernal and Her Cristalián de España: A Transcription and Study Candidate’s Name: Jodi Growitz Shearn Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2012 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Montserrat Piera This doctoral dissertation is a paleographic transcription of a Spanish chivalric romance written by Beatriz Bernal in 1545. Cristalián de España, as the text is referred to, was printed twice in its full book form, four parts and 304 folios. It was also well-received outside of the peninsula, and published twice in its Italian translation. This incunabulum is quite a contribution to the chivalric genre for many reasons. It is not only well-written and highly entertaining, but it is the only known Castilian romance of its kind written by a woman. This detail cannot be over-emphasized. Chivalric tales have been enjoyed for centuries and throughout many different mediums. Readers and listeners alike had been enjoying these romances years before the libros de caballerías reached the height of their popularity in Spain. -

List of Discussion Titles (By Title)

The “Booked for the Evening” book discussion group began March 1999. Our selections have included fiction, mysteries, science fiction, short stories, biographies, non-fiction, memoirs, historical fiction, and young adult books. We’ve been to Europe, Asia, the Middle East, South America, the Antarctic, Africa, India, Australia, Canada, Mexico, and the oceans of the world. We’ve explored both the past and the future. After more than 15 years and over two hundred books, we are still reading, discussing, laughing, disagreeing, and sharing our favorite titles and authors. Please join us for more interesting and lively book discussions. For more information contact the Roseville Public Library 586-445-5407. List of Discussion Titles (by title) 1984 George Orwell February 2014 84 Charring Cross Road Helene Hanff November 2003 A Cold Day in Paradise Steve Hamilton October 2008 A Patchwork Planet Anne Tyler July 2001 A Prayer for Owen Meany John Irving December 1999 A Room of One’s Own Virginia Wolff January 2001 A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian Marina Lewycka December 2008 The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian Sherman Alexie October 2010 Affliction Russell Banks August 2011 The Alchemist Paulo Coelho June 2008 Along Came a Spider James Patterson June 1999 An Inconvenient Wife Megan Chance April 2007 Anatomy of a Murder Robert Traver November 2006 Angela’s Ashes Frank McCourt August 1999 Angle of Repose Wallace Stegner April 2010 Annie's Ghosts: A Journey into a Family Secret Steve Luxenberg October 2013 Arc of Justice: a Saga of Race, Civil Rights and Murder in the Jazz Age Kevin Boyle February 2007 Around the World in Eighty Days Jules Verne July 2011 Page 1 of 6 As I Lay Dying William Faulkner July 1999 The Awakening Kate Chopin November 2001 Ballad of Frankie Silver Sharyn McCrumb June 2003 Before I Go to Sleep S. -

Age of Chivalry

The Constraints Laws on Warfare in the Western World War Edited by Michael Howard, George J. Andreopoulos, and Mark R. Shulman Yale University Press New Haven and London Robert C . Stacey 3 The Age of Chivalry To those who lived during them, of course, the Middle Ages, as such, did not exist. If they lived in the middleof anything, most medieval people saw themselves as living between the Incarnation of God in Jesus and the end of time when He would come again; theirown age was thus a continuation of the era that began in the reign of Caesar Augustus with his decree that all the world should be taxed. The Age of Chivalry, however, some men of the time- mostly knights, the chevaliers, from whose name we derive the English word "chivalry"-would have recognized as an appropriate label for the years between roughly I 100 and 1500.Even the Age of Chivalry, however, began in Rome. In the chansons de geste and vernacular histories of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Hector, Alexander, Scipio, and Julius Caesar appear as the quintessential exemplars of ideal knighthood, while the late fourth or mid-fifth century Roman military writer Vcgetius remained far and away the most important single authority on the strategy and tactics of battle, his book On Military Matters (De re military passing in transla- tion as The Book of Chivalry from the thirteenth century on. The Middle Ages, then, began with Rome; and so must we if we are to study the laws of war as these developed during the Age of Chivalry. -

The Christian Recovery of Spain, Being the Story of Spain from The

~T'^~r''m»^ STORY OF r>.e N ATJONS^rrrr: >' *•=• ?(¥**''' ^'i^^J^^^^'^'^^rP'.'fiS- «* j; *!v'---v-^^'--: "'I'l "i .'^l^lllL""ll'h i' [i^lLl^lA^AiiJ rr^^Tf iii Di ii i m im wmV' W M»\immmtmme>mmmm>timmms6 Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2008 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.arcliive.org/details/cliristianrecoverOOwattricli THE STORY OF THE NATIONS 2MO, ILLUSTRATED. PER VOL., $1.50 THE EARLIER VOLUMES ARE THE STORY OF GREECE. By Prof. Jas. A. Harrison THE STORY OF ROME. By Arthur Oilman THE STORY OF THE JEWS. By Prof. Jas. K. Hosmer THE STORY OF CHALDEA. By Z. A. Ragozin THE STORY OF GERMANY. By S. Baring-Gould THE STORY OF NORWAY. By Prof. H. H. Bovesen THE STORY OF SPAIN. By E. E. and Susan Hale THE STORY OF HUNGARY. By Prof. A. V.^MBfiRY THE STORY OF CARTHAGE. By Prof. Alfred J. Church THE STORY OF THE SARACENS. By Arthur Oilman THE STORY OF THE MOORS IN SPAIN. By Stanley Lane-Poole THE STORY OF THE NORMANS. By Sarah O. Jewett THE STORY OF PERSIA. By S. G. W. Benjamin THE STORY OF ANCIENT EGYPT. By Geo. Rawlinson THE STORY OF ALEXANDER'S EMPIRE. By Prof. J. P. Mahaffy THE STORY OF ASSYRIA. By Z. A. Ragozin THE STORY OF IRELAND. By Hon. Emilv Lawless THE STORY OF THE GOTHS. By Henry Bradley THE STORY OF TURKEY. By Stanley Lane-Poole THE STORY OF MEDIA, BABYLON, AND PERSIA. By Z. A. Ragozin THE STORY OF MEDIEVAL FRANCE. By Gustave Masson THE STORY OF MEXICO. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Free

FREE A KNIGHTS OWN BOOK OF CHIVALRY: GEOFFROI DE CHARNY PDF Geoffroi de Charny,Richard W. Kaeuper,Elspeth Kennedy | 128 pages | 12 May 2005 | University of Pennsylvania Press | 9780812219098 | English | Pennsylvania, United States Geoffroi de Charny - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Richard W. Kaeuper Introduction. Elspeth Kennedy Translator. On the great influence of a valiant lord: "The companions, who see that good warriors are honored by the great lords for their prowess, become more determined to attain this level of prowess. Read how an aspiring knight of the fourteenth century would conduct himself and learn what he would have needed to know when traveling, fighting, appearing in court, and engaging fellow knights. This is the most authentic and complete manual on the day-to-day life of the knight that has survived the centuries, and this edition contains a specially commissioned introduction from historian Richard W. Kaeuper that gives the history of both the book and its author, who, among his other achievements, was the original owner of the Shroud of Turin. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. -

Basics of the Church Sermon Title: Baptism Scripture Reading: Romans 6:1-11 Clearwater Bay International Baptist Church February 10, 2019 S.C

Sermon Series: Basics of the Church Sermon title: Baptism Scripture Reading: Romans 6:1-11 Clearwater Bay International Baptist Church February 10, 2019 S.C. Brown, Pastor Next week we will begin a new series called The Big Picture where we will take a look at the major themes of the Bible; somewhat of a Bible overview in several weeks. Before we do that next week, I have one free Sunday where I’d like to take the opportunity to tackle the topic of Baptism. What is Baptism? Why do we do it? What does it mean? How should we do it? You might think that is an easy question but maybe nothing has caused so much division amongst the Christian church as the topic of Baptism. Let’s pray together and ask God’s help. ————————————————————————- Our church is called Clearwater Bay International Baptist Church. Clearwater Bay kind of our area. International is who we are. We are a multiethnic congregation and in Hong Kong, “International” usually means our services are in English. But what about the B word…Baptist? Why is that there? Why are we Baptists? "1 Let me give you a simplified little history. Baptist groups came out of the Protestant Reformation in the 1500 & 1600’s because they didn’t baptize babies like almost everyone else. So, they were called ‘Anabaptists’, because they were baptized again, convinced that they were to be baptized as believers and not as infants. They were persecuted by Protestants and Catholics alike due to their getting baptized as adults, re-baptized, even though they had been baptized as babies. -

Movie Titles List, Genre

ALLEGHENY COLLEGE GAME ROOM MOVIE LIST SORTED BY GENRE As of December 2020 TITLE TYPE GENRE ACTION 300 DVD Action 12 Years a Slave DVD Action 2 Guns DVD Action 21 Jump Street DVD Action 28 Days Later DVD Action 3 Days to Kill DVD Action Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter DVD Action Accountant, The DVD Action Act of Valor DVD Action Aliens DVD Action Allegiant (The Divergent Series) DVD Action Allied DVD Action American Made DVD Action Apocalypse Now Redux DVD Action Army Of Darkness DVD Action Avatar DVD Action Avengers, The DVD Action Avengers, End Game DVD Action Aviator DVD Action Back To The Future I DVD Action Bad Boys DVD Action Bad Boys II DVD Action Batman Begins DVD Action Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice DVD Action Black Hawk Down DVD Action Black Panther DVD Action Blood Father DVD Action Body of Lies DVD Action Boondock Saints DVD Action Bourne Identity, The DVD Action Bourne Legacy, The DVD Action Bourne Supremacy, The DVD Action Bourne Ultimatum, The DVD Action Braveheart DVD Action Brooklyn's Finest DVD Action Captain America: Civil War DVD Action Captain America: The First Avenger DVD Action Casino Royale DVD Action Catwoman DVD Action Central Intelligence DVD Action Commuter, The DVD Action Dark Knight Rises, The DVD Action Dark Knight, The DVD Action Day After Tomorrow, The DVD Action Deadpool DVD Action Die Hard DVD Action District 9 DVD Action Divergent DVD Action Doctor Strange (Marvel) DVD Action Dragon Blade DVD Action Elysium DVD Action Ender's Game DVD Action Equalizer DVD Action Equalizer 2, The DVD Action Eragon -

Historical Tales: Spanish

Conditions and Terms of Use TABLE OF CONTENTS Copyright © Heritage History 2009 Some rights reserved THE GOOD KING WAMBA ....................................................... 3 THE GREEK KING'S DAUGHTER .............................................. 5 This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history books, and to the THE ENCHANTED PALACE ....................................................... 7 promotion of the works of traditional history authors. THE BATTLE OF GUADALETE .................................................. 9 HE ABLE OF OLOMON The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public domain and T T S ...................................................... 11 are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced THE STORY OF QUEEN EXILONA ........................................... 15 within the United States without paying a royalty to the author. PELISTES, THE DEFENDER OF CORDOVA ............................... 18 The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, however, are THE STRATAGEM OF THEODOMIR ......................................... 21 the property of Heritage History and are licensed to individual users with some THE CAVE OF COVADONGA .................................................. 23 restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the integrity HE DVENTURES OF A UGITIVE RINCE of the work itself, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure -

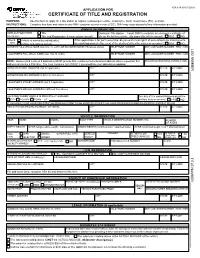

VSA 66 and Attach to This Form

APPLICATION FOR CERTIFICATE OF TITLE AND REGISTRATION PURPOSE: Use this form to apply for a title and/or to register a passenger vehicle, motorcycle, truck, motor home (RV), or trailer. INSTRUCTIONS: Complete this form and return to any DMV customer service center (CSC). DMV may request proof of any information provided. OWNER INFORMATION APPLICATION TYPE: Title Electronic Title Option -- I want DMV to maintain an electronic certificate of Check one: Title and Registration (license plates issued) title on file for this vehicle. (No paper title will be issued) YES NO Check Vehicle is owned by individual(s). If this application is for joint ownership, do you wish clear rights of ownership to be transferred to one: Vehicle is business owned. the surviving owner in the event of the death of either the owner or co-owner? YES NO OWNER'S FULL LEGAL NAME (last, first, mi, suffix) OR BUSINESS NAME (if business owned) TELEPHONE NUMBER DMV CUSTOMER NUMBER / FEIN / SSN LOG NUMBER ____________________________________ CO-OWNER'S FULL LEGAL NAME (last, first, mi, suffix) TELEPHONE NUMBER DMV CUSTOMER NUMBER / FEIN / SSN NOTE: Owners (and Lessees if applicable) MUST provide their residence/home/business address where requested, this RESIDENCE/BUSINESS JURISDICTION address can not be a P.O. Box. You must complete form ISD-01 if you would like your address(es) updated. OWNER'S STREET ADDRESS (Apt # if applicable) CITY STATE ZIP CODE OWNER'S MAILING ADDRESS (if different from above) CITY STATE ZIP CODE CO-OWNER'S STREET ADDRESS (Apt # if applicable) CITY STATE ZIP CODE CO-OWNER'S MAILING ADDRESS (if different from above) CITY STATE ZIP CODE LOCATION WHERE VEHICLE IS PRINCIPALLY GARAGED Are any of the owners/lessees on active CITY COUNTY TOWN OF military duty or service? YES NO IF YOU WOULD LIKE YOUR REGISTRATION RENEWALS SENT TO AN ADDRESS OTHER THAN YOUR RESIDENCE/BUSINESS ADDRESS, ENTER IT BELOW. -

A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Free Download

A KNIGHTS OWN BOOK OF CHIVALRY: GEOFFROI DE CHARNY FREE DOWNLOAD Geoffroi de Charny,Richard W. Kaeuper,Elspeth Kennedy | 128 pages | 12 May 2005 | University of Pennsylvania Press | 9780812219098 | English | Pennsylvania, United States A Knight's Own Book of Chivalry Other Editions 3. As for the over bearing message of Christianity throughout the text it, it was written in 13th century France, of course it's going to be filled with overt religious tones - everyone was then. Beware the "holier-than-thou". Geoffroi also goes on to describe ball games as a women's sport that men have wrongly taken from them! Kaeuper A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny. Geoffroi's fortitude and devotion become apparent almost immediately and I couldn't help but admire him. Thus, the great lords in particular must be temperate in their eating habits, avoid gambling and greed, indulge only in honorable pastimes such as jousting and maintaining the company of ladies, keep any romantic liaisons secret, and—most importantly—only be found in the company of worthy men. He says nothing about spiritual counseling, community service, or politics whatsoever. Lists with This Book. A neat article. Geoffroi isn't much for games, but knows that young men will inevitably play them. Once, when he was captured by the English, Geoffroi's captor actually released him, trusting him to go back home to raise money for his own ransom which, as far as we can tell, Geoffroi actually did. Books A Knights Own Book of Chivalry: Geoffroi De Charny Geoffroi De Charny. -

Download PDF Datastream

AN ‘AMIABLE ENMITY’: FRONTIER SPECTACLE AND INTERCULTURAL RELATIONS IN CASTILE AND CYPRUS by Thomas C. Devaney B.A., Trinity College, 1998 M.A.T., Boston College, 2000 M.A., University of Chicago, 2004 Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RI MAY 2011 This dissertation by Thomas Connaught Devaney is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:___________________ ____________________________________ Amy Remensnyder, Director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:___________________ ____________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Reader Date:___________________ ____________________________________ Tara Nummedal, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:___________________ ____________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School ii CURRICULUM VITAE Thomas Devaney was born December 27, 1976 in New York City. He attended Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut from 1994 to 1998, where he earned a B.A. in History and received the Ferguson Prize in History for the honors thesis, “Fragmenting Social Tensions within the United Irish Movement, 1780-1797.” He later attended the Lynch School of Education at Boston College from 1999-2000, finishing with an M.A.T. in Secondary Curriculum and Instruction. After teaching history and social studies in several middle and high schools in the Boston area, he returned to graduate school in 2003 at the University of Chicago, where he studied with Walter Kaegi and Rachel Fulton. He completed his studies at Chicago in 2004, earning a M.A. in Social Sciences. After a year of study in Latin, French, and German at the University of Illinois at Chicago, he enrolled at Brown to work with Amy Remensnyder in the Department of History.