Dazed and Confused: Russian “Information Warfare” and the Middle East – the Syria Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia's Role in the Horn of Africa

Russia Foreign Policy Papers “E O” R’ R H A SAMUEL RAMANI FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE • RUSSIA FOREIGN POLICY PAPERS 1 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Author: Samuel Ramani The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy- oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities. Eurasia Program Leadership Director: Chris Miller Deputy Director: Maia Otarashvili Editing: Thomas J. Shattuck Design: Natalia Kopytnik © 2020 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute July 2020 OUR MISSION The Foreign Policy Research Institute is dedicated to producing the highest quality scholarship and nonpartisan policy analysis focused on crucial foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. We educate those who make and influence policy, as well as the public at large, through the lens of history, geography, and culture. Offering Ideas In an increasingly polarized world, we pride ourselves on our tradition of nonpartisan scholarship. We count among our ranks over 100 affiliated scholars located throughout the nation and the world who appear regularly in national and international media, testify on Capitol Hill, and are consulted by U.S. government agencies. Educating the American Public FPRI was founded on the premise that an informed and educated citizenry is paramount for the U.S. -

Reel-Multimedia.Ch

reel-multimedia.ch TV - Programme Nr. Name Sprache Nr. Name Sprache Nr. Name Sprache 1 SRF 1 HD dt. 63 intv HD dt. 125 Uninettuno University ital. 2 SRF 2 HD dt. 64 Reg. Fernsehen HD dt. 126 Rai Gulp ital. 3 SRF-Info HD dt. 65 Ulm-Algäu HD dt. 127 Class TV Moda ital. 4 3 plus dt. 66 Bibel TV HD dt. 128 RTL 102.5 HD ital. 5 RTS Un HD franz. 67 K-TV dt. 129 Radio Italia TV HD ital. 6 RTS Deux HD franz. 68 n-tv dt. 130 Radionorba TV ital. 7 RSI LA 1 HD ital. 69 Welt dt. 131 TVE Inter. span. 8 RSI LA 2 HD ital. 70 N24 Docu dt. 132 24 Horas span. 9 Das Erste HD dt. 71 Euronews German SD dt. 133 RT Esp HD span. 10 tagesschau 24 HD dt. 72 Eurosport 1 dt. 134 Telesur span. 11 One HD dt. 73 Sport 1 dt. 135 TVGA span. 12 ZDF HD dt. 74 SKY Sport News HD dt. 136 Canal sur A. span. 13 ZDF info HD dt. 75 Astro TV dt. 137 Extremadura SAT span. 14 ZDF_neo HD dt. 76 Immer etwas Neues dt. 138 Hispan TV span. 15 Südwest BW HD dt. 77 Sonnenklar HD dt. 139 Cubavision span. 16 Südwest RP HD dt. 78 HSE 24 HD dt. 140 RTPI port. 17 SR Fernsehen HD dt. 79 QVC HD dt. 141 TV Record port. 18 Bayerisches FS HD dt. 80 Juwelo HD dt. 142 Dubai Intern. HD arab. 19 ARD-alpha dt. -

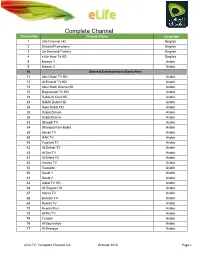

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Channel Package Orbital Position Satellite Language SD/HD/UHD 1+

Orbital Channel Package Satellite Language SD/HD/UHD Position EUTELSAT 1+1 13° EAST HOT BIRD UKRAINIEN SD CLEAR INTERNATIONAL 13D EUTELSAT 24 TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 2M MONDE 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 4 FUN FIT & DANCE RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT Cyfrowy 4 FUN HITS 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR Polsat 13C EUTELSAT 4 FUN HITS RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 4 FUN TV RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT Cyfrowy 4 FUN TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR Polsat 13C EUTELSAT 5 SAT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13B EUTELSAT 8 KANAL 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 8 KANAL EVROPE 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 90 NUMERI SAT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT AB CHANNEL Sky Italia 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13B EUTELSAT AB CHANNEL 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C ABN 13° EAST EUTELSAT ARAMAIC SD CLEAR HOT BIRD 13C EUTELSAT ABU DHABI AL 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE HD CLEAR OULA EUROPE 13B EUTELSAT ABU DHABI 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR SPORTS 1 13C EUTELSAT ABU DHABI ARABE, 13° EAST HOT BIRD SD CLEAR SPORTS EXTRA ANGLAIS 13C EUTELSAT ADA CHANNEL Sky Italia 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT AHL-E-BAIT TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD PERSAN SD CLEAR FARSI 13D EUTELSAT AL AOULA EUROPE SNRT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT AL AOULA MIDDLE SNRT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR EAST 13D EUTELSAT AL ARABIYA 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT -

Russia's Influence Campaign Targeting the 2016

Additional Questions for the Record of Senator Patrick Leahy Senate Judiciary Committee, Hearing on the Nomination of Senator Jeff Sessions to Serve as Attorney General of the United States January 25, 2017 Many answers to my written questions were non-responsive. While some answers quoted statutes and cases to support your position (e.g. Questions 4b, 11a, 15, 19a), in other responses you professed a complete lack of knowledge, even on topics that have dominated the news in recent months. You acknowledged in one response that you believe a statute is constitutional, but in others you refused even to say whether you considered a law to be “reasonably defensible.” When responding to these follow up questions, please review any necessary materials to provide substantive answers to my questions. I also was troubled by your responses to questions 8 and 22, in which you consistently did not answer the question directly and stated that you had “no knowledge of whether [an individual] actually said [remarks relevant to the question] or in what context.” Yet you omitted in your response footnotes that I included, which provided the relevant source material. I am re-asking those questions here and, for your convenience, I am appending these source materials to this document. Questions 8 and 22 8. In 2014, you accepted the “Daring the Odds” award from the David Horowitz Freedom Center. The Southern Poverty Law Center has repeatedly called David Horowitz an “anti- Muslim extremist” and has an extensive and detailed profile of Mr. Horowitz’s racist and repugnant remarks against Muslims, Arabs, and African-Americans. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Coastal Offensive

The Carter Center April 1, 2014 Syrian Armed Opposition Coastal Offensive The al-Anfal Campaign for the Syrian Coast By March 24th, the al-Anfal Campaign had On March 21, 2014 three armed opposition incorporated an additional member group, the groups, the Ansar al-Sham Battalions, the Islamic Ahrar al-Sham Movement.2 All groups al-Nusra Front, and the Sham al-Islam Move- participating in the campaign are particularly ment, announced the start of a high profile hard line, sharing a Salafi Islamist ideology and offensive in the northern countryside of the Lat- a high contingent of foreign fighters within their akia governorate on the Syrian coast.1 Named ranks. Some were previously involved in a sim- the al-Anfal Campaign on the Syrian Coast, the ilar offensive on the Syrian coast in late summer campaign seeks to expel government forces from 2013 where opposition forces were implicated in the Latakia countryside. the massacre of Alawite villages.3 1. [“Statement of the al-Anfal Campaign in the Syrian Coast”], Youtube video, posted by: “AboRyan Lattakia,” March 20, 2014, https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-ngB4fOZOwwww.youtube.com/watch?v=C-ngB4fOZOw 2. Twitter post, posted by: “@mhesne,” March 25, 2014, https://twitter.com/mhesne/status/448517844138229761 3. Jonathan Steele, “Syria: massacre reports emerge from Assad’s Alawite heartland,” October 2, 2013, The Guardian, http://www. theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/02/syria-massacre-reports-alawites-assad www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-ngB4fOZOw 1 The Carter Center The al-Nusra Front: Present throughout Syria, the group is the official al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria. -

Whither Obshestvennaya Diplomatiya? Assessing US Public

Whither Obshestvennaya Diplomatiya: Assessing U.S. Public Diplomacy in Post-Cold War Russia Author: Margot van Loon, School of International Service University Honors Advisor: J. Robert Kelley Spring 2013 Although a substantial amount of literature analyzes American public diplomacy in the Soviet Union, the level of scholarly interest in the region appears to have fallen with the Iron Curtain. There exists no comprehensive account of U.S. public diplomacy in Russia over the last twenty years, or any significant discussion of how these efforts have been received by the Russian public. This study addresses the gap in the literature by reconstructing the efforts of the last twenty years, providing an important case study for scholars of public diplomacy and of U.S.-Russia relations. Twelve policy officials, area experts, and public diplomats who had served in Moscow were interviewed to create a primary-source account of events in the field from 1989-2012. The taxonomy of public diplomacy, originally defined by Dr. Nicholas Cull, was then used to categorize each activity by primary purpose: listening, advocacy, cultural diplomacy, exchanges, and international broadcasting. These accounts were contextualized against the major events of the U.S.-Russia bilateral relationship in order to identify broad trends, successes and failures. The resulting narrative illustrates that U.S. public diplomacy in Russia suffers from a lack of top-down support from the U.S. government, from a restricted media environment that limits the success of advocacy and international broadcasting, and from the incongruity of messaging and actions that characterize the last two decades of the bilateral relationship. -

News Values on Instagram: a Comparative Study of International News

Article News Values on Instagram: A Comparative Study of International News Ahmed Al-Rawi 1,* , Alaa Al-Musalli 2 and Abdelrahman Fakida 1 1 School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Dr W K9671, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Business and Professional Studies, School of Communication, Capilano University, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, BC V7J 3H5, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study employs the news values theory and method in the examination of a large dataset of international news retrieved from Instagram. News values theory itself is subjected to critical examination, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses. Using a mixed method that includes content analysis and topic modeling, the study investigates the major news topics most ‘liked’ by Instagram audiences and compares them with the topics most reported on by news organizations. The findings suggest that Instagram audiences prefer to consume general news, human-interest stories and other stories that are mainly positive in nature, unlike news on politics and other topics on which traditional news organizations tend to focus. Finally, the paper addresses the implications of the above findings. Keywords: news values theory; Instagram news; social media; international news Citation: Al-Rawi, Ahmed, Alaa Al-Musalli, and Abdelrahman Fakida. 2021. News Values on Instagram: A Comparative Study of International 1. Introduction News. Journalism and Media 2: In this study, we use mixed methods to apply news values theory to examine audiences’ 305–320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ choices of news stories, comparing these preferences to the dominant news topics that journalmedia2020018 are highlighted by different international news organizations. -

ANTES ELEKTRONIK San Tic. Ltd. Şti KANAL ADI FREKANS FEC / Sempol Rate 4 Fun TV / Rodin TV / CSB TV 10719 V 27500 (5/6) Islam C

ANTES ELEKTRONIK San Tic. Ltd. Şti KANAL ADI FREKANS FEC / Sempol Rate 4 Fun TV / Rodin TV / CSB TV 10719 V 27500 (5/6) Islam Channel / Gem Music / RTP Internacional Europa / MTA International / Deepam TV / Global Tamil Vision Europe / Wedding TV Polska / Zagros TV / RTB Virgilio / Ariana 10723 H 29900 (3/4) Afghanistan TV / Andisheh TV / Ahl E Bait TV / Al Waad Channel / Didar Global TV / Private Spice Cyfrowy Polsat 10758 V 27500 (5/6) Sky Italia (HD) 10775 H 29900 (3/4) Tele 5 (Poland) / Polonia 1 / Edusat 10796 V 27500 (5/6) Baby TV Europe / 3ABN International / BVN TV Europa / CNL Evropa / Soyuz / Ru TV / Fashion TV Europe / Suryoyo Sat / KurdSat / MKTV Sat / Thai TV Global Network / VTV 4 / 10815 H 27500 (5/6) Rojhelat TV / ANN / ERT World / Daring! TV / TVK / Myanmar International / Universal TV / TV Verdade N (HD) 10834 V 27500 (3/4) Sky Italia (HD) 10853 H 29900 (3/4) Al Maghribia / Al Aoula Middle East / Al Aoula Maroc / Arrabia / Al Aoula Europe / Assadissa / Medi 1 TV / Arryadia / 10873 V 27500 (3/4) Tamazight Orange Polska (HD) 10911 V 27500 (3/4) Nova 10930 H 27500 (3/4) NourSat / ANB / Al Hiwar TV / Cartoon Network Central & Eastern Europe / Dhamma Media Channel / Miracle / ILike TV / Alforat TV / Alfady Channel / Disney Channel Polska / TCM 10949 V 27500 (3/4) Central & Eastern Europe / Deejay TV / Sat 7 Pars / Velayat TV Network / Karbala Satellite Channel / Al-Maaref TV (HD) SF 1 / SF Zwei / RTS Un / RTS Deux 10971 H 29700 (2/3) Rai Movie / Rai 1 / Rai 2 / Rai 3 / Rai 4 / Rai News 10992 V 27500 (2/3) Mediaset Extra / -

Press Release Affluent Africa 2018

PRESS RELEASE How digital is driving media growth in Africa African Affluent at the forefront of adopting new media technologies Embargoed until 08.00 GMT 13th of September 2018 Amsterdam. 13th September 2018. The 5th Affluent Survey Africa, released by Ipsos on September 13th, revealed: • Despite internet penetration in the continent lagging behind other regions of the world, Africa’s Affluent population have embraced digital technology more rapidly than their European counterparts: many more of them are watching TV on their tablets, computers and smartphones and more of them read their newspapers digitally. • International TV channels now enjoy a higher reach amongst the Affluent population than national channels • Social media is now considered the first port of call for news amongst a substantial proportion of the Affluent population The biennial study measures the media use and consumption behaviour of the top 15% of income earners in Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda. Growth of international media brands. In the past two years, there has been a major roll- out of digital television broadcasting services across the continent, increasing the availability and reach of many international media channels. On a monthly basis, 96% of the African Affluent population watch an international television network. In fact, on a daily level, the combined reach of international television channels – at 81% - is now higher than that of national channels, watched by 71% of this select group of people. While all types of international media are popular amongst Africa’s top 15%, the survey results show they are heavily business-news oriented. -

Russia's “Soft Power”

RUSSIA’S “SOFT POWER” STRATEGY A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies by Jill Dougherty, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. November 1, 2013 RUSSIA’S “SOFT POWER” STRATEGY Jill Dougherty, B.A. MALS Mentor: Angela Stent, Ph.D. ABSTRACT On October 30, 2013 the business-oriented Forbes.com put Russian President Vladimir Putin at the top of its list of “The World’s Most Powerful People,” unseating United States President Barack Obama. Forbes said its editors made the decision based on the power of the person over a large number of people, the financial resources controlled by the person, their power in multiple spheres, and the degree to which they actively use their power. Revisionist media commentary immediately followed the report, pointing out that Russia remains a regional power, that its economy, while improving, still ranks fifth in the world, significantly trailing those of the United States and China. The ranking also appeared to be, at least partially, a reaction to Russia’s skillful shift in diplomacy on the Syrian conflict, by which it proposed a plan to destroy the Assad regime’s chemical weapons. Others noted that Forbes is a conservative publication, and part of its editors’ motivation might have been the desire to criticize a Democratic President. It was, nevertheless, a stunning turn-about for Russia’s President, an indication of how quickly evaluations of a leader and his or her country can shift, based on their perceived influence. -

Useful Idiots' in the West: an Overview of RT's Editorial Strategy and Evidence of Impact

Kremlin Watch Report 10.09.2017 The Kremlin's Platform for 'Useful Idiots' in the West: An Overview of RT's Editorial Strategy and Evidence of Impact Kremlin Watch is a strategic program which Monika L. Richter Kremlin Watch is a strategic program, which aims aimsto expose to expose and confrontand confront instruments instruments of Russian of Kremlin Watch Program Analyst Russianinfluence andinfluence disinformation and operationsdisinformation focused operations focusedagainst Westernagainst democracies.Western democracies. The Kremlin's Platform for 'Useful Idiots' in the West: An Overview of RT's Editorial Strategy and Evidence of Impact Table of Contents 1. Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 Key points ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 3. Russia Today: Background and strategic objectives ......................................................................................................... 8 I. 2005 – 2008: A public diplomacy mandate .................................................................................................................... 8 II. 2008 – 2009: Reaction