Whither Obshestvennaya Diplomatiya? Assessing US Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia's Role in the Horn of Africa

Russia Foreign Policy Papers “E O” R’ R H A SAMUEL RAMANI FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE • RUSSIA FOREIGN POLICY PAPERS 1 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Author: Samuel Ramani The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy- oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities. Eurasia Program Leadership Director: Chris Miller Deputy Director: Maia Otarashvili Editing: Thomas J. Shattuck Design: Natalia Kopytnik © 2020 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute July 2020 OUR MISSION The Foreign Policy Research Institute is dedicated to producing the highest quality scholarship and nonpartisan policy analysis focused on crucial foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. We educate those who make and influence policy, as well as the public at large, through the lens of history, geography, and culture. Offering Ideas In an increasingly polarized world, we pride ourselves on our tradition of nonpartisan scholarship. We count among our ranks over 100 affiliated scholars located throughout the nation and the world who appear regularly in national and international media, testify on Capitol Hill, and are consulted by U.S. government agencies. Educating the American Public FPRI was founded on the premise that an informed and educated citizenry is paramount for the U.S. -

CONGRESSIONAL PROGRAM U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era

CONGRESSIONAL PROGRAM U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era May 29 – June 3, 2018 Helsinki, Finland and Tallinn, Estonia Copyright @ 2018 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute 2300 N Street Northwest Washington, DC 20037 Published in the United States of America in 2018 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era May 29 – June 3, 2018 The Aspen Institute Congressional Program Table of Contents Rapporteur’s Summary Matthew Rojansky ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Russia 2018: Postponing the Start of the Post-Putin Era .............................................................................. 9 John Beyrle U.S.-Russian Relations: The Price of Cold War ........................................................................................ 15 Robert Legvold Managing the U.S.-Russian Confrontation Requires Realism .................................................................... 21 Dmitri Trenin Apple of Discord or a Key to Big Deal: Ukraine in U.S.-Russia Relations ................................................ 25 Vasyl Filipchuk What Does Russia Want? ............................................................................................................................ 39 Kadri Liik Russia and the West: Narratives and Prospects ......................................................................................... -

Reel-Multimedia.Ch

reel-multimedia.ch TV - Programme Nr. Name Sprache Nr. Name Sprache Nr. Name Sprache 1 SRF 1 HD dt. 63 intv HD dt. 125 Uninettuno University ital. 2 SRF 2 HD dt. 64 Reg. Fernsehen HD dt. 126 Rai Gulp ital. 3 SRF-Info HD dt. 65 Ulm-Algäu HD dt. 127 Class TV Moda ital. 4 3 plus dt. 66 Bibel TV HD dt. 128 RTL 102.5 HD ital. 5 RTS Un HD franz. 67 K-TV dt. 129 Radio Italia TV HD ital. 6 RTS Deux HD franz. 68 n-tv dt. 130 Radionorba TV ital. 7 RSI LA 1 HD ital. 69 Welt dt. 131 TVE Inter. span. 8 RSI LA 2 HD ital. 70 N24 Docu dt. 132 24 Horas span. 9 Das Erste HD dt. 71 Euronews German SD dt. 133 RT Esp HD span. 10 tagesschau 24 HD dt. 72 Eurosport 1 dt. 134 Telesur span. 11 One HD dt. 73 Sport 1 dt. 135 TVGA span. 12 ZDF HD dt. 74 SKY Sport News HD dt. 136 Canal sur A. span. 13 ZDF info HD dt. 75 Astro TV dt. 137 Extremadura SAT span. 14 ZDF_neo HD dt. 76 Immer etwas Neues dt. 138 Hispan TV span. 15 Südwest BW HD dt. 77 Sonnenklar HD dt. 139 Cubavision span. 16 Südwest RP HD dt. 78 HSE 24 HD dt. 140 RTPI port. 17 SR Fernsehen HD dt. 79 QVC HD dt. 141 TV Record port. 18 Bayerisches FS HD dt. 80 Juwelo HD dt. 142 Dubai Intern. HD arab. 19 ARD-alpha dt. -

Russian American Pacific Partnership

Russian American Pacific Partnership SUMMARY REPORT 17th Annual Meeting Tacoma, Washington September 19-20, 2012 2012 RAPP Sponsors: RAPP Secretariats’ Joint Letter Our deep thanks to all the participants of the 17th annual meeting! Following the meeting, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Commerce Mat- thew Murray wrote, “You have created an outstanding forum for both public and private stakeholders in improving U.S.-Russia commercial ties. The en- thusiasm and level of interest from participants and the input we received has helped support our bilateral initiatives with Russia”. There are objective reasons to believe now is an excellent opportunity to expand U.S.-Russian cooperation across the Pacific. Both Russia and the U.S. have stated their intent to make the Asia Pacific a priority in their eco- nomic strategy. Russia has created its new Ministry of Far East Affairs (Development) elevating the development of the Russian Far East to among the highest of national priorities. Following their successful APEC host year, Russia and the Russian Far East are most interested to demonstrate results in international economic cooperation. Over the past year, U.S. exports to Russia grew impressively and are accelerating in 2012. Once the U.S. establishes with Russia Perma- nent Normal Trade Relation status, U.S. companies can benefit from Rus- sia’s WTO accession commitments making Russia an even more attractive business market. The renewed opportunity for U.S. West Coast trade with the regions of the Russian Far East benefits our companies and consumers, broadens U.S.-Russian commerce, and adds balance to our international trade relations at the regional level. -

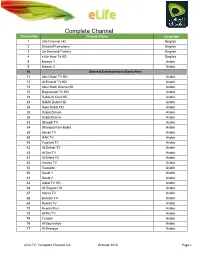

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Monterey Summer Symposium on Russia

MONTEREY SUMMER SYMPOSIUM ON RUSSIA June 28 – August 4 2021 Friday, June 18 10:00 a.m. – Экскурсия по Арзамасу. 1:00 p.m. Российские медиа: выбор Дзядко Touring Arzamas Academy. Russian Media Landscape: Dzyadko’s Choice Семейный музей: Монтерей 2021 Personal Histories: Monterey 2021 Filipp Dzyadko (in Russian) All times are Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) 2 Saturday, June 19 10:00 a.m. – Семейный музей: Монтерей 2021 1:00 p.m. Personal Histories: Monterey 2021 Filipp Dzyadko (in Russian) All times are Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) 3 Monday, June 21 Elective Week 10:00 a.m. – Making Your Policy Point for TV, Radio and the 1:30 p.m.* Educated Public Matthew Rojansky *Duration depends on number of participants Jill Dougherty (presentations in English) All times are Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) 4 Tuesday, June 22 Elective Week 10:00 a.m. – Policy Thinking* 10:50 a.m. Q&A Michael Kimmage (lecture in English) 10:50 a.m. – Break 11:00 a.m. 11:00 a.m. – Россия и Запад: три традиции 11:40 a.m. Russia and the West: Three Traditions Andrei Pavlovich Tsygankov (lecture in Russian) 11:40 a.m. – Break 12:00 p.m. 12:00 p.m. – My Tenure as U.S. Ambassador to the Russian 12:50 p.m. Federation Thomas R. Pickering (lecture in English) 12:50 p.m. – Break 1:00 p.m. 1:00 p.m. – 1:50 Review of Novikov and Roberts Telegrams p.m. Q&A Michael Kimmage (lecture in English) * Key presentation for Diplomatic Writing Module These are for fellows who intend to take full Diplomatic Workshop All times are Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) 5 Wednesday, June 23 Elective Week 10:00 a.m. -

Steven Pifer

Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS POLICY PAPER Number 10, January 2009 Reversing the Decline: An Agenda for U.S.-Russian Relations in 2009 Steven Pifer The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, D.C. 20036 brookings.edu Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS POLICY PAPER Number 10, January 2009 Reversing the Decline: An Agenda for U.S.-Russian Relations in 2009 Steven Pifer Acknowledgements am grateful to John Beyrle, Ian Kelly, Michael O’Hanlon, Carlos I Pascual, Theodore Piccone, Strobe Talbott and Alexander Versh- bow for the comments and suggestions that they provided on earlier drafts of this paper. I would also like to express my appreciation to Gail Chalef and Ian Livingston for their assistance. Finally, I would like to thank Daniel Benjamin and the Center on the United States and Europe for their support. Foreign Policy at Brookings iii Table of Contents Introduction and Summary . 1 The Decline in U.S.-Russia Relations . 3 What Does Russia Want? .................................. 7 An Agenda for Engaging Russia in 2009 . 11 Implementing the Agenda .................................21 Endnotes............................................... 25 Foreign Policy at Brookings v Introduction and Summary s the Bush administration comes to a close, Building areas of cooperation not only can advance AU.S.-Russian relations have fallen to their low- specific U.S. goals, it can reduce frictions on other est level since the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. issues. Further, the more there is to the bilateral re- Unresolved and problematic issues dominate the lationship, the greater the interest it will hold for Rus- agenda, little confidence exists between Washington sia, and the greater the leverage Washington will have and Moscow, and the shrill tone of official rhetoric with Moscow. -

Channel Package Orbital Position Satellite Language SD/HD/UHD 1+

Orbital Channel Package Satellite Language SD/HD/UHD Position EUTELSAT 1+1 13° EAST HOT BIRD UKRAINIEN SD CLEAR INTERNATIONAL 13D EUTELSAT 24 TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 2M MONDE 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 4 FUN FIT & DANCE RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT Cyfrowy 4 FUN HITS 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR Polsat 13C EUTELSAT 4 FUN HITS RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 4 FUN TV RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT Cyfrowy 4 FUN TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR Polsat 13C EUTELSAT 5 SAT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13B EUTELSAT 8 KANAL 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 8 KANAL EVROPE 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 90 NUMERI SAT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT AB CHANNEL Sky Italia 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13B EUTELSAT AB CHANNEL 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C ABN 13° EAST EUTELSAT ARAMAIC SD CLEAR HOT BIRD 13C EUTELSAT ABU DHABI AL 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE HD CLEAR OULA EUROPE 13B EUTELSAT ABU DHABI 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR SPORTS 1 13C EUTELSAT ABU DHABI ARABE, 13° EAST HOT BIRD SD CLEAR SPORTS EXTRA ANGLAIS 13C EUTELSAT ADA CHANNEL Sky Italia 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT AHL-E-BAIT TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD PERSAN SD CLEAR FARSI 13D EUTELSAT AL AOULA EUROPE SNRT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT AL AOULA MIDDLE SNRT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR EAST 13D EUTELSAT AL ARABIYA 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT -

Russia's Influence Campaign Targeting the 2016

Additional Questions for the Record of Senator Patrick Leahy Senate Judiciary Committee, Hearing on the Nomination of Senator Jeff Sessions to Serve as Attorney General of the United States January 25, 2017 Many answers to my written questions were non-responsive. While some answers quoted statutes and cases to support your position (e.g. Questions 4b, 11a, 15, 19a), in other responses you professed a complete lack of knowledge, even on topics that have dominated the news in recent months. You acknowledged in one response that you believe a statute is constitutional, but in others you refused even to say whether you considered a law to be “reasonably defensible.” When responding to these follow up questions, please review any necessary materials to provide substantive answers to my questions. I also was troubled by your responses to questions 8 and 22, in which you consistently did not answer the question directly and stated that you had “no knowledge of whether [an individual] actually said [remarks relevant to the question] or in what context.” Yet you omitted in your response footnotes that I included, which provided the relevant source material. I am re-asking those questions here and, for your convenience, I am appending these source materials to this document. Questions 8 and 22 8. In 2014, you accepted the “Daring the Odds” award from the David Horowitz Freedom Center. The Southern Poverty Law Center has repeatedly called David Horowitz an “anti- Muslim extremist” and has an extensive and detailed profile of Mr. Horowitz’s racist and repugnant remarks against Muslims, Arabs, and African-Americans. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Coastal Offensive

The Carter Center April 1, 2014 Syrian Armed Opposition Coastal Offensive The al-Anfal Campaign for the Syrian Coast By March 24th, the al-Anfal Campaign had On March 21, 2014 three armed opposition incorporated an additional member group, the groups, the Ansar al-Sham Battalions, the Islamic Ahrar al-Sham Movement.2 All groups al-Nusra Front, and the Sham al-Islam Move- participating in the campaign are particularly ment, announced the start of a high profile hard line, sharing a Salafi Islamist ideology and offensive in the northern countryside of the Lat- a high contingent of foreign fighters within their akia governorate on the Syrian coast.1 Named ranks. Some were previously involved in a sim- the al-Anfal Campaign on the Syrian Coast, the ilar offensive on the Syrian coast in late summer campaign seeks to expel government forces from 2013 where opposition forces were implicated in the Latakia countryside. the massacre of Alawite villages.3 1. [“Statement of the al-Anfal Campaign in the Syrian Coast”], Youtube video, posted by: “AboRyan Lattakia,” March 20, 2014, https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-ngB4fOZOwwww.youtube.com/watch?v=C-ngB4fOZOw 2. Twitter post, posted by: “@mhesne,” March 25, 2014, https://twitter.com/mhesne/status/448517844138229761 3. Jonathan Steele, “Syria: massacre reports emerge from Assad’s Alawite heartland,” October 2, 2013, The Guardian, http://www. theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/02/syria-massacre-reports-alawites-assad www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-ngB4fOZOw 1 The Carter Center The al-Nusra Front: Present throughout Syria, the group is the official al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria. -

The Ambassadorial Series a Collection of Transcripts from the Interviews

The Ambassadorial Series A Collection of Transcripts from the Interviews COMPILED AND EDITED BY THE MONTEREY INITIATIVE IN RUSSIAN STUDIES MIDDLEBURY INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES MAY 10, 2021 ii Introduction At a time when dialogue between American and Russian diplomats is reduced to a bare minimum and when empathy and civility fall short of diplomacy between major powers, we are pleased to introduce the Ambassadorial Series. It is a compilation of conversations with eight outstanding American diplomats who served at various points of time as U.S. ambassadors to the Soviet Union and, after its dissolution, to the Russian Federation. The Series provides nuanced analyses of crucial aspects of the U.S.-Russia relationship, such as the transition from the Soviet Union to contemporary Russia and the evolution of Putin’s presidency. It does so through the personal reflections of the ambassadors. As Ambassador Alexander Vershbow observes, “[t]he Ambassadorial Series is a reminder that U.S. relations with Putin's Russia began on a hopeful note, before falling victim to the values gap.” At its heart, this project is conceived as a service to scholars and students of American diplomacy vis-à-vis Russia. The interviews, collected here as transcripts, form a unique resource for those who want to better understand the evolving relationship between the two countries. We would like to express gratitude to our colleagues who collaborated on this project and to the Monterey Initiative in Russian Studies staff members who supported it. Jill Dougherty is the face and voice of this project – bringing expertise, professionalism, and experience to the Series. -

News Values on Instagram: a Comparative Study of International News

Article News Values on Instagram: A Comparative Study of International News Ahmed Al-Rawi 1,* , Alaa Al-Musalli 2 and Abdelrahman Fakida 1 1 School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Dr W K9671, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Business and Professional Studies, School of Communication, Capilano University, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, BC V7J 3H5, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study employs the news values theory and method in the examination of a large dataset of international news retrieved from Instagram. News values theory itself is subjected to critical examination, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses. Using a mixed method that includes content analysis and topic modeling, the study investigates the major news topics most ‘liked’ by Instagram audiences and compares them with the topics most reported on by news organizations. The findings suggest that Instagram audiences prefer to consume general news, human-interest stories and other stories that are mainly positive in nature, unlike news on politics and other topics on which traditional news organizations tend to focus. Finally, the paper addresses the implications of the above findings. Keywords: news values theory; Instagram news; social media; international news Citation: Al-Rawi, Ahmed, Alaa Al-Musalli, and Abdelrahman Fakida. 2021. News Values on Instagram: A Comparative Study of International 1. Introduction News. Journalism and Media 2: In this study, we use mixed methods to apply news values theory to examine audiences’ 305–320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ choices of news stories, comparing these preferences to the dominant news topics that journalmedia2020018 are highlighted by different international news organizations.