Understanding RT's Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter from Dame Melanie Dawes to Rt Hon Damian Green MP on The

Dame Melanie Dawes Chief Executive [email protected] Rt Hon Damian Green MP House of Commons London SW1A OAA 30 July 2021 Dear Damian, Thank you for your email about BBC coverage of the Olympics, the deal with Discovery, and how these arrangements fit with our code on listed events. There has been significant press coverage of the issues, and the BBC have commented on them too, so I thought it would be helpful to outline the current arrangements, how the code applies in this case and some of the implications for the future. As you may know, the broadcasting arrangements applying to the Tokyo Games are the result of deals done some years ago. In 2012 the BBC acquired the exclusive UK broadcast rights for live coverage of both summer and winter Olympics up to and including the current Games. However, in 2015 Discovery reached an agreement with the IOC for a multimedia rights package encompassing fifty countries in Europe. That deal included the UK broadcast and on-demand rights for live coverage of the 2022 and 2024 Games. Subsequently, in 2016, the BBC agreed to sub-licence pay-TV rights to the current Games, in return for free-to-air rights to the 2022 and 2024 Games. As part of this sub-licencing deal, during the current Games the BBC is allowed to show two live streams at any one time from whichever events it chooses. The reason for concentrating on the rights is that they, rather than the actual coverage provided by a broadcaster of a listed event, are the focus of the current legislative regime. -

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fern German channels PHOENIX and sehen) is Germany’s national KiKA, and the European chan public television. It is run as an nels 3sat and ARTE. independent nonprofit corpo ration under the authority of The corporation has a permanent the Länder, the sixteen states staff of 3,600 plus a similar number that constitute the Federal of freelancers. Since March 2012, Republic of Germany. ZDF has been headed by Direc torGeneral Thomas Bellut. He The nationwide channel ZDF was elected by the 60member has been broadcasting since governing body, the ZDF Tele 1st April 1963 and remains one vision Council, which represents of the country’s leading sources the interests of the general pub of information. Today, ZDF lic. Part of its role is to establish also operates the two thematic and monitor programme stand channels ZDFneo and ZDFinfo. ards. Responsibility for corporate In partnership with other pub guide lines and budget control lic media, ZDF jointly operates lies with the 14member ZDF the internetonly offer funk, the Administrative Council. ZDF’s head office in Mainz near Frankfurt on the Main with its studio complex including the digital news studio and facilities for live events. Seite 2 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF is based in Mainz, but also ZDF offers fullrange generalist maintains permanent bureaus in programming with a mix of the 16 Länder capitals as well information, education, arts, as special editorial and production entertainment and sports. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

00 Muncie 4E BAB1408B0166

00_Muncie_4e_BAB1408B0166_Prelims.indd 3 18-Nov-14 9:13:10 PM 1 Youth Crime: Representations, Discourses and Data Chapter 1 examines: • the concepts of ‘crime’, ‘youth’, ‘criminalization’ and ‘social construction’; • how young people have come to be regarded as a threat; • how the ‘problem of youth’ is frequently collapsed into the problem of crime and disorder; • how young people are represented in media and political discourses; • the reliability of statistical measures of youth offending; • the gendered nature of offending; • the relationship between gangs and violent crime; • the relationship between drug use and criminality. Key terms corporate crime; crime; criminalization; delinquency; demonization; deviance; discourse; folk devil; gang; hidden crime; moral panic; official statistics; protective factors; recording of crime; reporting of crime; representation; risk factors; self-report studies; social con- structionism; status offence; youth This introductory chapter is designed to promote a critical understanding of the relationship between youth and crime. The equation of these two terms is widely employed and for many is accepted as common sense. Stories about youth and crime are a mainstay of most forms of media. Official crime statistics are readily and uncritically recited to substantiate a view that youth crime and disorder are now ‘out of control’. But how far do the media reflect social reality and how much are they able to define it? How valid and reliable is statistical evidence? By asking these questions, the chapter draws attention to how the state of youth and the 01_Muncie_4e_BAB1408B0166_Ch-01.indd 1 11/18/2014 8:40:00 PM problem of crime come to be defined in particular circumscribed ways. -

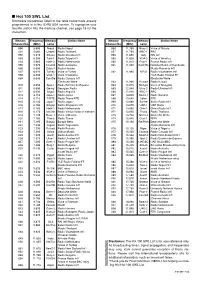

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Scotland's Digital Media Company

Annual Report and Accounts 2010 Annual Report and Accounts Scotland’s digital media company 2010 STV Group plc STV Group plc In producing this report we have chosen production Pacific Quay methods which aim to minimise the impact on our Glasgow G51 1PQ environment. The papers chosen – Revive 50:50 Gloss and Revive 100 Uncoated contain 50% and 100% recycled Tel: 0141 300 3000 fibre respectively and are certified in accordance with the www.stv.tv FSC (Forest stewardship Council). Both the paper mill and printer involved in this production are environmentally Company Registration Number SC203873 accredited with ISO 14001. Directors’ Report Business Review 02 Highlights of 2010 04 Chairman’s Statement 06 A conversation with Rob Woodward by journalist and media commentator Ray Snoddy 09 Chief Executive’s Review – Scotland’s Digital Media Company 10 – Broadcasting 14 – Content 18 – Ventures 22 KPIs 2010-2012 24 Performance Review 27 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 29 Corporate Social Responsibility Corporate Governance 34 Board of Directors 36 Corporate Governance Report 44 Remuneration Committee Report Accounts 56 STV Group plc Consolidated Financial Statements – Independent Auditors’ Report 58 Consolidated Income Statement 58 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 59 Consolidated Balance Sheet 60 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 61 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 62 Notes to the Financial Statements 90 STV Group plc Company Financial Statements – Independent Auditors’ Report 92 Company Balance Sheet 93 Statement -

Lara Marie Müller

Lara Marie M¨uller Doctoral Candidate Contact Information Email: [email protected] Phone: +49 151 651 050 44 Academic Education PhD in Economics since 2020 University of Cologne, Cologne Graduate School of Economics Research Interest: Media Economics and Economics of Digitization Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,Prof. Dr. Bettina Rockenbach Double Degree: Master in Economics 2018 - 2020 University of Cologne, Germany (M.Sc.) and Keio University, Japan (M.A.) One year of studies at each institution Bachelor of Science in Economics 2014 - 2018 University of Cologne Including two exchange semesters: - Warsaw School of Economics, Poland (SS2016) - Pontif´ıciaUniversidade Cat´olicado Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (WS2015/16) Research Interest I am interested in how we can design media markets that best serve society. For this, I aim to conduct mainly experimental research to gain insights on Welfare effects on digital media markets, for example in the context of personalisation or misinformation. Professional Experience Research Associate since 07/2020 Chair of Media Economics, Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,University of Cologne Teaching: Exercise in Media Economics (Bachelor and Master), Seminar on Media Mar- kets (Bachelor), Supervision of Bachelor Theses Freelance Journalist 2018 - 2020 Covering mainly economics for German news outlets, magazines and broadcasters. Cus- tomers included: Handelsblatt, Welt am Sonntag, ada, Die Welt, WDR, FAZ.net, Frank- furter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, among others. Lecturer at K¨olnerJournalistenschule -

Notes and References

Notes and References Introduction 1. Simon Lee, The Cost of Free Speech (London: Faber, 1990) p. ix. 2. The wonderfully judicious and precise phrase ‘adequate to the predicament’ is one of the gifts bequeathed by the late Seamus Heaney, in his collection North. 3. An example is Peter Jones’s otherwise brilliant essay ‘Respecting Beliefs and Rebuking Rushdie’, British Journal of Political Science, 20:4, 1990, pp. 415–37. 4. Andrew Gibson, Postmodernity, Ethics and the Novel: From Leavis to Levinas (London: Routledge, 1999). 5. The phrase ‘civilization-speak’ is Heiko Henkel’s. See his essay, ‘“The journalists of Jyllands-Posten are a bunch of reactionary provocateurs”: The Danish Cartoon Controversy and the Self-Image of Europe,’ Radical Philosophy, 137, 2006, p. 2. 6. Glen Newey, ‘Unlike a Scotch Egg’, London Review of Books, 35:23, 5 December 2013, p. 22. 1 From Blasphemy to Offensiveness: the Politics of Controversy 1. In using the term ‘the Rushdie affair’ as a shorthand for the controversy over The Satanic Verses, I concur with Paul Weller who notes the Muslim objections to it on the grounds that it seemingly trivialized what was, in fact, an event of momentous significance. It does retain, however, a certain currency even now and was the dominant marker at the time, used in many documents and sources that I will have occasion to quote. I will therefore use it alongside other descriptive terminol- ogy such as ‘The Satanic Verses controversy’. 2. Paul Weller, A Mirror for Our Times: ‘The Rushdie Affair’ and the Future of Multiculturalism (London: Continuum, 2009). -

Russia's Role in the Horn of Africa

Russia Foreign Policy Papers “E O” R’ R H A SAMUEL RAMANI FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE • RUSSIA FOREIGN POLICY PAPERS 1 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Author: Samuel Ramani The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy- oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities. Eurasia Program Leadership Director: Chris Miller Deputy Director: Maia Otarashvili Editing: Thomas J. Shattuck Design: Natalia Kopytnik © 2020 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute July 2020 OUR MISSION The Foreign Policy Research Institute is dedicated to producing the highest quality scholarship and nonpartisan policy analysis focused on crucial foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. We educate those who make and influence policy, as well as the public at large, through the lens of history, geography, and culture. Offering Ideas In an increasingly polarized world, we pride ourselves on our tradition of nonpartisan scholarship. We count among our ranks over 100 affiliated scholars located throughout the nation and the world who appear regularly in national and international media, testify on Capitol Hill, and are consulted by U.S. government agencies. Educating the American Public FPRI was founded on the premise that an informed and educated citizenry is paramount for the U.S. -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence.