BECOMING PAN-EUROPEAN? Transnational Media and the European Public Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

An Film Partners, Zdf / Arte, Mam, Cnc, Medienboard Berlin Brandenburg Comme Des Cinemas, Nagoya Broadcasting Network and Twenty Twenty Vision

COMME DES CINEMAS, NAGOYA BROADCASTING NETWORK AND TWENTY TWENTY VISION AN FILM PARTNERS, ZDF / ARTE, MAM, CNC, MEDIENBOARD BERLIN BRANDENBURG COMME DES CINEMAS, NAGOYA BROADCASTING NETWORK AND TWENTY TWENTY VISION SYNOPSIS Sentaro runs a small bakery that serves dorayakis - pastries filled with sweet red bean paste(“an”) . When an old lady, Tokue, offers to help in the kitchen he reluctantly accepts. But Tokue proves to have magic in her hands when it comes to making “an”. Thanks to her secret recipe, the little business soon flourishes… And with time, Sentaro and Tokue will open their hearts to reveal old wounds. 113 minutes / Color / 2.35 / HD / 5.1 / 2015 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Cherry trees in full bloom remind us of death. I do not know of any other tree whose flowers blossom in such a spectacular way, only to have their petals scatter just as suddenly. Is this the reason behind our fascination for blossoming cherry trees? Is this why we are compelled to see a reflection of our own lives in them? Sentaro, Tokue and Wakana meet when the cherry trees are in full bloom. The trajectories of these three people are very different. And yet, their souls cross paths and meet one another in the same landscapes. Our society is not always predisposed to letting our dreams become reality. Sometimes, it swallows up our hopes. After learning that Tokue is infected with leprosy, the story pulls us into a quest for the very essence of what makes us human. As a director, I have the honour and pleasure of exploring different lives through cinema, as is the case with this film. -

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fern German channels PHOENIX and sehen) is Germany’s national KiKA, and the European chan public television. It is run as an nels 3sat and ARTE. independent nonprofit corpo ration under the authority of The corporation has a permanent the Länder, the sixteen states staff of 3,600 plus a similar number that constitute the Federal of freelancers. Since March 2012, Republic of Germany. ZDF has been headed by Direc torGeneral Thomas Bellut. He The nationwide channel ZDF was elected by the 60member has been broadcasting since governing body, the ZDF Tele 1st April 1963 and remains one vision Council, which represents of the country’s leading sources the interests of the general pub of information. Today, ZDF lic. Part of its role is to establish also operates the two thematic and monitor programme stand channels ZDFneo and ZDFinfo. ards. Responsibility for corporate In partnership with other pub guide lines and budget control lic media, ZDF jointly operates lies with the 14member ZDF the internetonly offer funk, the Administrative Council. ZDF’s head office in Mainz near Frankfurt on the Main with its studio complex including the digital news studio and facilities for live events. Seite 2 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF is based in Mainz, but also ZDF offers fullrange generalist maintains permanent bureaus in programming with a mix of the 16 Länder capitals as well information, education, arts, as special editorial and production entertainment and sports. -

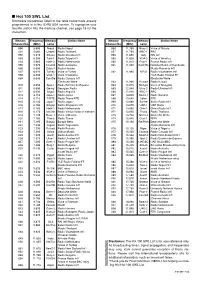

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems

institut montaigne MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems REPORT MAY 2019 MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE” MEDIA POLARIZATION There is no desire more natural than the desire for knowledge MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems MAY 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In France, representative democracy is experiencing a growing mistrust that also affects the media. The latter are facing major simultaneous challenges: • a disruption of their business model in the digital age; • a dependence on social networks and search engines to gain visibility; • increased competition due to the convergence of content on digital media (competition between text, video and audio on the Internet); • increased competition due to the emergence of actors exercising their influence independently from the media (politicians, bloggers, comedians, etc.). In the United States, these developments have contributed to the polarization of the public square, characterized by the radicalization of the conservative press, with significant impact on electoral processes. Institut Montaigne investigated whether a similar phenomenon was at work in France. To this end, it led an in-depth study in partnership with the Sciences Po Médialab, the Sciences Po School of Journalism as well as the MIT Center for Civic Media. It also benefited from data collected and analyzed by the Pew Research Center*, in their report “News Media Attitudes in France”. Going beyond “fake news” 1 The changes affecting the media space are often reduced to the study of their most visible symp- toms. For instance, the concept of “fake news”, which has been amply commented on, falls short of encompassing the complexity of the transformations at work. -

Lara Marie Müller

Lara Marie M¨uller Doctoral Candidate Contact Information Email: [email protected] Phone: +49 151 651 050 44 Academic Education PhD in Economics since 2020 University of Cologne, Cologne Graduate School of Economics Research Interest: Media Economics and Economics of Digitization Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,Prof. Dr. Bettina Rockenbach Double Degree: Master in Economics 2018 - 2020 University of Cologne, Germany (M.Sc.) and Keio University, Japan (M.A.) One year of studies at each institution Bachelor of Science in Economics 2014 - 2018 University of Cologne Including two exchange semesters: - Warsaw School of Economics, Poland (SS2016) - Pontif´ıciaUniversidade Cat´olicado Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (WS2015/16) Research Interest I am interested in how we can design media markets that best serve society. For this, I aim to conduct mainly experimental research to gain insights on Welfare effects on digital media markets, for example in the context of personalisation or misinformation. Professional Experience Research Associate since 07/2020 Chair of Media Economics, Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,University of Cologne Teaching: Exercise in Media Economics (Bachelor and Master), Seminar on Media Mar- kets (Bachelor), Supervision of Bachelor Theses Freelance Journalist 2018 - 2020 Covering mainly economics for German news outlets, magazines and broadcasters. Cus- tomers included: Handelsblatt, Welt am Sonntag, ada, Die Welt, WDR, FAZ.net, Frank- furter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, among others. Lecturer at K¨olnerJournalistenschule -

Presentation November 2008

Presentation November 2008 1 Disclaimer All forward-looking statements are TF1 management’s present expectations of future events and are subject to a number of factors and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from those described in the forward-looking statements. 2 Financial Results 3 Consolidated revenue evolution (1/2) 9 Months 9 Months % €M 2007 2008 2007 2008/2007 Total Revenue 1,880.3 1,970.3 2,763.6 -4.6 % Incl. TF1 Channel Advertising 1,187.8 1,228.7 1,718.3 - 3.3 % Incl. Other Activities 692.5 741.6 1,045.3 -6.6 % H1 H1 Q3 Q3 €M % % 2008 2007 2008 2007 Total Revenue 1,363.5 1,430.6 -4.7 % 516.8 539.7 -4.2 % Incl. TF1 Channel Advertising 891.2 924.7 - 3.6 % 296.6 304.0 -2.4 % Incl. Other Activities 472.3 505.9 - 6.6 % 220.2 235.7 -6.6 % 4 Consolidated revenue evolution (2/2) 9 Months 9 Months €M 2007 2008 2007 (*) France Broadcasting 1,539.8 1,587.5 2,220.5 TF1 Channel 1,193.1 1,235.9 1,729.3 Téléshopping group 109.4 110.9 153.1 Thematic channels in France 138.3 138.0 188.6 TF1 Entreprises 20.8 21.7 40.5 In-house production companies 24.0 23.1 28.1 e-tf1 38.1 42.6 57.4 Others 16.1 15.3 23.5 Audiovisual Rights 105.9 177.9 268.1 Catalogue 39.0 70.7 101.4 TF1 Video 66.9 107.2 166.7 International Broadcasting 234.0 204.9 274.8 Other Activities 0.6 - 0.2 Total revenue 1,880.3 1,970.3 2,763.6 (*) Reclassification of TF1 Hors Média (non-media below-the-line promotional activities) from TF1 Entreprises to Other after its merger into TF1 Publicité, and of WAT from Other to e-TF1 5 A tough economic situation Evolution of advertising revenue by sector (for TF1) Gross revenue (January-October 2008) Evol Jan-Oct. -

Brésil Selon Le Monde Diplomatique Et Le Courrier International

i Uaiversite Lumiere Lyon II : MEMCMHE DE DEA Sciences de Flttformation et de la Communication )n ; Langage et symboliques de la commtiiiicatien et des medias LE BRESIL SELON LE MONDE DIFLOMATIQUE ET LE COURRIER INTERNATIONAI, Les sources d,$'nformati.on et ieur paroie dans la formation de 1'opiiiion Marcio Augusto FLEXA SANTOS Sous la direction de : Jean-Fmngois' Titu DE L ENSSIB \ Septembre 1999 812411 Jmverswc lumiere leole Natieaak Seperieere Urthe.^de Jese. Mmlia ? Des Seieneeti d« rlBferraatitta Lyoa 3 et cies Eibiieteques B-mmb Universite Lumiere Lyon II MEMOIRE DE DEA Sciences de 1'Information et de la Communication Option : Langage et symboliques de la communication et |< ^O/c,l 1,-B ' des medias % • LE BRESIL SELON LE MONDE DIPLOMATIQUE ET LE COURRIER INTERNATIONAL Les sources d'information et leur parole dans la formation de 1'opinion Marcio Augusto FLEXA SANTOS Sous la direction de : Jean-Frangois Tetu Septembre 1999 Universite lumiere Ecole Nationaie Superieure Universite Jean Moulin Lvon 2 Des Sciences de i'Information Lvon 3 et des Bibiioteques O C? Q Enssib 'X £ H z, J Universite Lumiere Lyon II MEMOIRE DE DEA Sciences de 1'Information et de la Communicatlon Option : Langage et symboliques de la communication et des medias LE BRESIL SELON LE MONDE DIPLOMATIQUE ET LE COURRIERINTERNATIONAL Les sources d'information et leur parole dans la formation de 1'opinion Marcio Augusto FLEXA SANTOS Sous la direction de: Jean-Frangois Tetu Septembre 1999 Universite lumiere Ecole Nationale Superieure Universite Jean Moulin Lyon 2 Des Sciences de l'Information Lyon 3 et des Biblioteques Enssib REMERCIEMENTS Ce travail n 'aurait pu voir le jour sans le soutien constant et les encouragements de M. -

Liberation Technology Conference Bios

1 Liberation Technology in Authoritarian Regimes October 11‐12, 2010 Bechtel Conference Center, Encina Hall, Stanford University Conference Attendees’ Bios Esra’a Al Shafei, MideastYouth.com Esra'a Al Shafei is the founder and Executive Director of MideastYouth.com, a grassroots, indigenous digital network that leverages the power of new media to facilitate the struggle against oppression in the Middle East and North Africa. She is a recipient of the Berkman Award from Harvard University's Berkman Center for Internet and Society for "outstanding contributions to the internet and its impact on society," and is currently a TED Fellow and an Echoing Green Fellow. Most recently, her project won a ThinkSocial Award for serving as a "powerful model for how social media can be used to address global problems." Walid Al‐Saqaf, Yemen Portal Walid AL‐SAQAF is a Yemeni activist, software engineer and scholar concerned with studying Internet censorship around the world, but with a special focus on the Middle East. During 1999‐ 2005, he held the position of publisher and editor‐in‐chief of Yemen Times, which was founded by his father in 1990 and since 2009, he has been a PhD candidate at Örebro University in Sweden, where he also teaches online investigative journalism. In 2010, he won a TED fellowship and the Democracy award of Örebro University for his research and activism in promoting access to information and for fighting cyber censorship. Among his notable works is Yemen Portal (https://yemenportal.net), which is a news aggregator focused on content on Yemen and alkasir (https://alkasir.com), a unique censorship circumvention software solution that allows Internet users around the world to access websites blocked by regimes. -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence. -

TV News Channels in Europe: Offer, Establishment and Ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018

TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018 Director of publication Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director Editorial supervision Gilles Fontaine, Head of Department for Market Information Author Laura Ene, Analyst European Television and On-demand Audiovisual Market European Audiovisual Observatory Proofreading Anthony A. Mills Translations Sonja Schmidt, Marco Polo Sarl Press and Public Relations – Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] European Audiovisual Observatory Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France Tel.: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax. : +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] http://www.obs.coe.int Cover layout – ALTRAN, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France Please quote this publication as Ene L., TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership, European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2018 © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, July 2018 If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership Laura Ene Table of contents 1. Key findings ...................................................................................................................... -

The Six Day War and the French Press, 1967

Three Visions of Conflict: The Six Day War and the French Press, 1967 Robert Isaacson The George Washington University Abstract: Examination of the journalistic coverage of the 1967 Arab-Israeli Six Day War by the French mainstream media reveals the centrality of the war experience as a turning point in French public discourse on Israel. Shared assumptions about Israel's vulnerability were replaced by diverse and often contradictory discourses of religious triumphalism, territorial revisionism, and ideological anti-imperialism. This analysis shows that French President Charles de Gaulle's interpretation of the war was far from dominant, and indicates that French public discourse on Israel was fractured and diverse, responsive to different events, and far from the monolith that polling that would suggest. In November 1967, five months after Israel's dramatic victory in the June 5 to June 10 Six Day War, French President Charles de Gaulle publically ended the "tacit alliance" that had existed between France and Israel since the early 1950s.1 In a nationally broadcast speech, de Gaulle expressed his frustration with Israel by critiquing Jews broadly, calling them "an elite people, sure of themselves and domineering...charged [with] burning and conquering ambition," and blamed the war on Israeli territorial aspirations.2 These statements were a far cry from those de Gaulle had made only a decade prior, when he told then-Herut Party chairman, Menachem Begin, "Don't let go of Gaza. It is a sector essential for your security."3 The November remarks drew fire from critics in France and Israel who saw the words as antisemitic and cementing his "betrayal" of Israel on the eve of the Six Day War by adopting a policy of "active neutrality."4 This policy, itself a gesture meant to boost relations with the Arab world, threatened condemnation on whichever party initiated hostilities, and preemptively moved to cut off arms shipments to Israel.