Living with Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

![Découvrez Le Guide Production 2010 [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3971/d%C3%A9couvrez-le-guide-production-2010-pdf-1863971.webp)

Découvrez Le Guide Production 2010 [Pdf]

GUIDE Producteurs_Couv:Mise en page 1 21/01/10 20:12 Page 1 Les Guides de l’Académie Toscan du Plantier Daniel prix césar2010 prix Daniel 2010 Toscan du Plantier Les producteurs du Cinéma français en 2009 césar Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma 16 avenue Élisée Reclus - 75007 Paris www.lescesarducinema.com GUIDE Producteurs_Couv:Mise en page 1 21/01/10 20:12 Page 2 Ce guide recense les productrices et les producteurs délégué(e)s des films sortis en salle en 2009 et concourant pour le César du Meilleur Film 2010. C'est parmi eux que les jurés vont choisir le lauréat 2010 du «Prix Daniel Toscan du Plantier», Association pour la Promotion du Cinéma dont le nom sera dévoilé lors de la soirée de remise du prix le 22 février 2010. 16, avenue Élisée Reclus 75007 Paris Ce guide a été établi conformément aux dispositions de l'article 1 du règlement du Président: Alain Terzian «Prix Daniel Toscan du Plantier». Directeur de la publication: Alain Rocca Toutes les informations qu'il contient correspondent aux données communiquées par Conception: Maria Torme et Jérôme Grou-Radenez les sociétés de production ou le CNC. Réalisation et impression: Global Rouge, Les Deux-Ponts Guide imprimé sur papier labélisé issu de forêts gérées durablement © APC, toute reproduction, même partielle, interdite www.lescesarducinema.com [email protected] Guide Producteurs_100p:Guide Technique 21/01/10 20:02 Page 1 sommaire Éditorial d’Alain Terzian Président de l’Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma page 3 Éditorial de Bruno Petit Président du Directoire de Fortis Banque France page 5 Liste des productrices et des producteurs éligibles pour le «Prix Daniel Toscan du Plantier» 2010 page 7 Règlement du «Prix Daniel Toscan du Plantier» page 97 Guide Producteurs_100p:Guide Technique 21/01/10 20:02 Page 2 2 Guide Producteurs_100p:Guide Technique 21/01/10 20:02 Page 3 Alain Terzian Président de l’Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma Daniel Toscan du Plantier était un homme passionné tourné vers l’avenir. -

4 Modern Shakespeare Festivals

UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA ESCUELA INTERNACIONAL DE DOCTORADO Festival Shakespeare: Celebrating the Plays on the Stage Festival Shakespeare: Celebrando las Obras en la Escena Dª Isabel Guerrero Llorente 2017 Page intentionally left blank. 2 Agradecimientos / Acknoledgements / Remerciments Estas páginas han sido escritas en lugares muy diversos: la sala becarios en la Universidad de Murcia, la British Library de Londres, el centro de investigación IRLC en Montpellier, los archivos de la National Library of Scotland, la Maison Jean Vilar de Aviñón, la biblioteca del Graduate Center de la City University of New York –justo al pie del Empire State–, mi habitación en Torre Pacheco en casa de mis padres, habitaciones que compartí con Luis en Madrid, Londres y Murcia, trenes con destinos varios, hoteles en Canadá, cafeterías en Harlem, algún retazo corregido en un avión y salas de espera. Ellas son la causa y el fruto de múltiples idas y venidas durante cuatro años, ayudándome a aunar las que son mis tres grandes pasiones: viajar, el estudio y el teatro.1 Si bien los lugares han sido esenciales para definir lo que aquí se recoge, aún más primordial han sido mis compañeros en este viaje, a los que hoy, por fin, toca darles las gracias. Mis primeras gracias son para mi directora de tesis, Clara Calvo. Gracias, Clara, por la confianza depositada en mí estos años. Gracias por propulsar tantos viajes intelectuales. Gracias también a Ángel-Luis Pujante y Vicente Cervera, quienes leyeron una versión preliminar de algunos capítulos y cuyos consejos han sido fundamentales para su mejora. Juanfra Cerdá fue uno de los primeros lectores de la propuesta primigenia y consejero excepcional en todo este proceso. -

Archives Audiovisuelles Du Théâtre National De Chaillot

Archives audiovisuelles du Théâtre National de Chaillot Répertoire numérique détaillé du versement 20160438 Justine Dilien, sous la direction de la Mission des archives du ministère de la Culture et de la communication. Sandrine Gill, Archives nationales, Département de l'archivage électronique et des archives audiovisuelles. Première édition électronique Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2018 1 Mention de note éventuelle https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_055964 Cet instrument de recherche a été rédigé avec un logiciel de traitement de texte. Ce document est écrit en français. Conforme à la norme ISAD(G) et aux règles d'application de la DTD EAD (version 2002) aux Archives nationales, il a reçu le visa du Service interministériel des Archives de France le ..... 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Niveau de description sous-fonds Intitulé Archives audiovisuelles du Théâtre National de Chaillot Date(s) extrême(s) 1966-2014 Nom du producteur • Théâtre national de Chaillot (Paris) Importance matérielle et support 1762 supports analogiques et numériques, 575 vidéos numériques. Localisation physique Fontainebleau Conditions d'accès Les archives, sous leur forme numérique, sont librement consultables, selon le règlement de la salle de lecture. Conditions d'utilisation Toute exploitation (reproduction, réutilisation) est soumise au droit de la propriété intellectuelle. Documents de substitution A l'Institut National de l'Audiovisuel (INA) DESCRIPTION Présentation du contenu Ce versement est constitué par des archives audiovisuelles produites ou reçues par le Théâtre National de Chaillot. Seuls quelques spectacles identifiés de ce versement datent du Théâtre National Populaire (à partir de 1971), la plupart ayant été produits sous l'égide du Théâtre National de Chaillot (après 1975). -

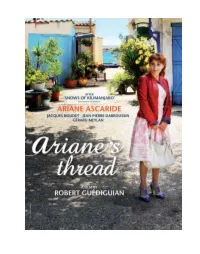

Ariane's Thread Is Also MY Ariane’S Thread

AGAT Films & Cie presents ARIANE’S THREAD A film by Robert Guédiguian with Ariane ASCARIDE Jacques BOUDET, Jean-Pierre DARROUSSIN, Anaïs DEMOUSTIER Youssouf DJAORO, Adrien JOLIVET, Gérard MEYLAN and Lola NAYMARK 92min – 1.85 – 5.1 – DCP International Sales FILMS DISTRIBUTION 34, rue du Louvre – 75001 Paris, France www.filmsdistribution.com Ph : 01.53.10.33.99 SYNOPSIS _____________________________________________________________________ Ariane, a middle-aged woman, is lonelier than ever in her pretty house. It's her birthday. The candles on the birthday cake are lit. But all of her loved ones have sent their apologies - they're not coming. So she takes her pretty car and leaves her pretty suburban neighborhood to get lost in the big sunny city of Marseille. CAST ____________________________________________________________________ Ariane ASCARIDE Jacques BOUDET Jean-Pierre DARROUSSIN Anaïs DEMOUSTIER Youssouf DJAORO Adrien JOLIVET Gérard MEYLAN Lola NAYMARK Judith MAGRE, doing the voice of the turtle INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT GUÉDIGUIAN _____________________________________________________________________ Where did you get the idea for Ariane’s Thread? I wanted to make a film just for the pleasure of making it, in a completely free style, like a theatrical “impromptu” or improvisation - a little, fast-paced poetic piece, that would be exhilarating and pure fun. I also had a strong desire to let go, to simply perform for the sake of it. The screenplay needed to be a “performance vessel” for the actors, the technicians and of course, for myself. With the exception of Le Promeneur du Champ-de-Mars [The Last Mitterand], in which she wasn’t cast, you have written 16 films for Ariane Ascaride. -

Un Train Pour Milan

AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE L’ADAMI DÉCLENCHEUR UN TRAIN POUR MILAN SACD n° 000318887 AVEC FRANÇOIS FEROLETO ET LA VOIX DE MICHEL BOUQUET D’APRÈS LES ŒUVRES DE DINO BUZZATI É CRIT ET MIS EN SCÈ NE PAR CHRISTOPHE GAND & FRANÇOIS FEROLETO COLLABORATION ARTISTIQUE GAËLLE BILLAUT- DANNO 1 FESTIVAL OFF D’AVIGNON 2020 THÉÂTRE LA LUNA 1, rue Séverine 84000 Avignon Tel : +33 4 90 86 96 28 – Email : [email protected] https://theatre-laluna.fr Du vendredi 3 au dimanche 26 juillet à 17h25 Relâches les mercredis 8, 15 & 22 Durée : 1h15 2 UN TRAIN POUR MILAN UN SPECTACLE ÉCRIT CHRISTOPHE GAND ET MIS EN SCÈNE PAR & FRANÇOIS FEROLETO D’APRÈS LES ŒUVRES DE DINO BUZZATI AVEC FRANÇOIS FEROLETO ET LA VOIX DE MICHEL BOUQUET COLLABORATION ARTISTIQUE GAËLLE BILLAUT-DANNO SCÉNOGRAPHIE GOURY LUMIÈRE DENIS KORANSKY COSTUMES JEAN-DANIEL VUILLERMOZ RÉGIE SÉBASTIEN CHORIOL PRODUCTION JÉRÔME RÉVEILLÈRE DURÉE 1H15 3 MENTIONS DE PRODUCTION page 5 SYNOPSIS page 6 EXTRAITS page 7 UN MOT DE CHRISTOPHE GAND pages 8 UN MOT DE FRANÇOIS FEROLETO page 9-11 UN MOT DE GAËLLE BILLAUT-DANNO page 12 CV FRANÇOIS FEROLETO pages 13 CV CHRISTOPHE GAND page 14 CV GAËLLE BILLAUT DANNO page 15 ÉQUIPE ARTISTIQUE pages 17-18 4 MENTIONS DE PRODUCTION PRODUCTION PARFUM DE SCÈNES PRODUCTION EXÉCUTIVE ZOAQUE 7 COPRODUCTION Accueilli en résidence de création au Théâtre du Rempart de Semur-en-Auxois PARTENAIRES Le spectacle bénéficie de l’aide à la création et diffusion – ADAMI DÉCLENCHEUR. « L’Adami gère et fait progresser les droits des artistes-interprètes en France et dans le monde. -

David Brécourt

AU COIN DE LA LUNE, PARFUM DE SCÈNES, COQ HÉRON PRODUCTIONS, LES PRODUCTIONS PM & ZOAQUE 7 PRÉSENTENT EN CE TEMPS DE GILLES SÉGAL MISE EN SCÈNE CHRISTOPHE GAND AVEC LÀ DAVID BRÉCOURT L’AMOURScénographie Costumes Lumière Musique originale Nils Zachariasen Jean-Daniel Vuillermoz Denis Koransky Raphaël Sanchez LICENCES 2 ET 3 N°1086032 / 1086033 LICENCES 2 ET ÉQUIPE ARTISTIQUE AUTEUR / GILLES SÉGAL MISE EN SCÈNE / CHRISTOPHE GAND AVEC / DAVID BRÉCOURT SCÉNOGRAPHIE / NILS ZACHARIASEN COSTUMES / JEAN-DANIEL VUILLERMOZ LUMIÈRE / DENIS KORANSKY MUSIQUE ORIGINALE / RAPHAËL SANCHEZ FESTIVAL OFF D’AVIGNON 2019 PRODUCTION / JÉRÔME RÉVEILLÈRE THÉÂTRE AU COIN DE LA LUNE 24, rue Buffon - 84000 Avignon DIFFUSION / MARINA DEFOSSE Tel : +33 04 90 39 87 29 Email : [email protected] PRESSE / CÉCILE MOREL https://www.theatre-aucoindelalune.fr Du vendredi 5 au dimanche 28 juillet à 11 h 10 Relâche les mardis 9, 16 & 23 Durée : 1 h 10 2 3 MENTIONS DE PRODUCTION PRODUCTION / PARFUM DE SCÈNES, COQ HÉRON PRODUCTIONS, PROMETHEE PRODUCTIONS & LES PRODUCTIONS PM SYNOPSIS PRODUCTION EXÉCUTIVE / ZOAQUE 7 Z. vient tout juste d’être grand-père. Il se décide alors à enregistrer pour son fils, sur bandes magnétiques, un souvenir gravé à jamais dans sa mémoire : sa rencontre avec un père Accueilli en résidence de création à et son jeune garçon dans le train qui L’Âne Vert Théâtre à Fontainebleau les conduisait aux camps de la mort. Le temps du trajet, ignorant le chaos Le texte est publié chez LANSMAN ÉDITEUR qui s’installe de jour en jour dans le wagon, ce père va profiter de chaque instant pour transmettre à son fils PARTENAIRES l’essentiel de ce qui aurait pu faire Le spectacle bénéficie de l’aide à la création et diffusion – de lui un homme. -

Télécharger Le Rapport D'activité 2013

RAPPORT D’ACTIVITÉ 2013 Rapport d’activité 2013 TABLE DES MATIERES EDITORIAL ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 I LES ACTIVITES PROPOSEES AU PUBLIC EN 2013..........................................................................................5 1 LA PROGRAMMATION DES FILMS ................................................................................................................................... 6 2 LES EXPOSITIONS..................................................................................................................................................... 10 3 L’ACTION CULTURELLE .............................................................................................................................................. 20 4 LA BIBLIOTHEQUE DU FILM......................................................................................................................................... 26 5 LA LIBRAIRIE............................................................................................................................................................ 28 6 LES INVITES DE LA CINEMATHEQUE ............................................................................................................................ 29 II LES COLLECTIONS............................................................................................................................................31 1 ENRICHISSEMENT -

Archives Sonores Du Théâtre National De Chaillot

Archives sonores du Théâtre national de Chaillot Répertoire numérique détaillé du versement 20170371 Justine Dilien, sous la direction de la Mission des archives du ministère de la Culture et de la communication. Sandrine Gill, Archives nationales, Département de l'archivage électronique et des archives audiovisuelles. Première édition électronique Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2018 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_056791 Cet instrument de recherche a été rédigé dans le système d'information archivistique des Archives nationales. Ce document est écrit en français. Conforme à la norme ISAD(G) et aux règles d'application de la DTD EAD (version 2002) aux Archives nationales. 2 Mentions de révision : • 2020: Cet intrument de recherche a été révisé en 2020 par Sandrine Gill, suite à la numérisation d'une majorité de supports audiovisuels. 3 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 20170371/1-20170371/119 Niveau de description sous-fonds Intitulé Archives sonores du Théâtre national de Chaillot Date(s) extrême(s) 1967-2011 Nom du producteur • Théâtre national de Chaillot (Paris) Importance matérielle et support 334 supports sonores analogiques et numériques : bandes magnétiques, mini-disc, cassettes audio numériques, disquettes, CD, memory disc. Les fichiers numériques extraits des CD, disquettes ainsi que les fichiers issus de la numérisation de certains supports sont indiqués dans le corps de l'instrument de recherche. Localisation physique Fontainebleau Conditions d'accès Les archives sont librement consultables. Conditions d'utilisation Toute exploitation (reproduction, réutilisation) est soumise au droit de la propriété intellectuelle. DESCRIPTION Présentation du contenu Ce versement est constitué d'enregistrements d'extraits sonores, d'enregistrements de représentations, ainsi que de quelques textes. -

PROGRAM GUIDE JULY 6 - 12, 2018 Seven Days of French Cinema at the Riviera Theatre a PARIS EDUCATION (MES PROVINCIALES) CUSTODY (JUSQU’À LA GARDE)

SBIFF The Wave FILM FESTIVAL France PROGRAM GUIDE JULY 6 - 12, 2018 Seven Days of French Cinema at the Riviera Theatre A PARIS EDUCATION (MES PROVINCIALES) CUSTODY (JUSQU’À LA GARDE) Étienne comes to Paris from the countryside to study filmmaking Miriam seeks sole custody of her son, Julien, to protect him from a at the Sorbonne. There he meets Mathias and Jean-Noël, two father she claims is violent. Antoine pleads his case as a scorned students who share his passion for cinema. In addition to studying, dad whose children were turned against him by their vindictive they must face friendship and love challenges, as well as choose mother. Unsure who is telling the truth, the judge grants joint cus- their artistic battles. A pensive study in black and white, this film is tody. A hostage to the escalating conflict between his parents, “a declaration of love for classic film and the city of Paris.” (Berli- Julien is pushed to the edge to prevent the worst from happening. nale) Written & Directed by: Xavier Legrand Written & Directed by: Jean-Paul Civeyrac Starring: Denis Ménochet, Léa Drucker, Thomas Gioria, Mathilde Starring: Andranic Manet, Gonzague Van Bervesselès, Corentin Auneveux Fila, Diane Rouxel, Jenna Thiam Runtime: 93 minutes Runtime: 137 minutes CARBON (CARBONE) ELEMENTARY (PRIMAIRE) Faced with the threat of losing his transport business, Antoine Roca Florence is a schoolteacher who is devoted to her students. When concocts a scam which will become the burglary of the century. she encounters young Sacha, a disruptive child with significant Entangled with gangsters, he must face betrayal, murder, and the problems, she wants to do everything she can to help him, even to settling of scores. -

Robin Renucci Maryline Canto Thomas Chabrol Jean-François Balmer

PATRICK GODEAU PRESENTS SCREENPLAY BY ODILE BARSKI AND CLAUDE CHABROL ROBIN RENUCCI MARYLINE CANTO THOMAS CHABROL JEAN-FRANÇOIS BALMER INTEGRAL FILM www.livressedupouvoir.com PAN-EUROPÉENNE PATRICK GODEAU PRESENTS ISABELLE HUPPERT FRANÇOIS BERLÉAND PATRICK BRUEL IN A COMEDY OF POWER AFILMBY CLAUDE CHABROL WRITTEN BY ODILE BARSKI AND CLAUDE CHABROL Running time: 1h50 / Format: 1.85 / Sound: SRD - DTS complete French text and images available at http://www.livressedupouvoir.com www.pan-europeenne.com SYNOPSIS Judge Jeanne Charmant is assigned the job of investigating and untangling a complex case of embezzlement and misappropriation of public funds, and bringing a case against the president of a powerful industrial conglomorate. As the investigation takes shape, as her questions dig deeper, she feels her power growing: the more secrets she penetrates, the greater her means of applying pressure. At the same time, and for the same reasons, her private life begins to fall apart. She is quickly confronted with two vital, inescapable questions: How far can she extend her power before colliding with a greater one? And for how long can human nature resist growing drunk on this power? Will she emerge shattered? Starring Isabelle Huppert and François Berléand, Claude Chabrol's A COMEDY OF POWER is the work of an undisputed master still at the height of his powers. INTERVIEW WITH You move back and forth with a disconcerting CLAUDE CHABROL DIRECTOR fluidity between the public and private stakes. For me it was essential. I admit that I desire "I still believe in the class struggle and hope that fluidity more and more, all the more so as I very those who are worst exploited can squeeze the rarely find it in cinema nowadays. -

NICOLE GARCIA Réalisatrice Par Véronique Krahenbuhl (N° 20 Du 14 Mai 2000)

DOSSIER PEDAGOGIQUE Fiche artistique Nathalie Baye Camille Valmont Jacques Boudet Jacquet Sacha Briquet Albert Susan Carlson Martha Marie Daëms Graziella Jacquet Henri Garcin Agent de Camille Michelle Goddet Marie-Ange Miki Manojlovic Adrian Felicie Pasotti Gaëlle Frédérique Ruchaud La Nurse Joachim Serreau Vincent Gilles Treton Stephane Frantet Jacques Vincey Lombard Jean-Loup Wolff Hertz Fiche technique Réalisatrice Nicole Garcia Dialogues Jacques Fieschi Producteur Alain Sarde Musique Oswald d' Andrea Directeur de la photo William Lubtchansky Montage Agnès Guillemot Directeur de la décoration Jean-Baptiste Poirot Directrice des costumes Lyvia D'Alche Ingénieur du son Jean-Pierre Duret Son Jean-Paul Loublier 2 Synopsis en français Ce drame français, qui n’est ni un mélodrame excessif ni un jugement moral, dépeint le portrait réaliste d’une femme dont l’égocentrisme exacerbé détruit inexorablement la vie. Les désirs de célébrité de cette femme, Camille Valmont, occultent tous les autres aspects de sa vie. Quand elle devient une vedette reconnue, elle laisse partir son mari et ses deux jeunes enfants. Le tribunal limite les droits de visite des enfants à un week-end sur deux, peu lui importe, elle préfère se consacrer à sa carrière plutôt que de jouir de ce droit. Puis sa carrière commence à décliner. Camille, à court d’argent, accepte la moindre proposition de cachet. Un jour, elle obtient une courte mission en tant qu’hôtesse pour le Rotary Club de Vichy. Malheureusement, cette date coïncide avec son week-end de visite. Elle décide finalement de concilier les deux en emmenant les enfants avec elle à Vichy, alors que cela lui est formellement interdit par le tribunal.