RECONFIGURING the MACRO URBAN LANDSCAPE of BUCHAREST BASED on ITS NATIVE TRAITS Stan Angelica Assoc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

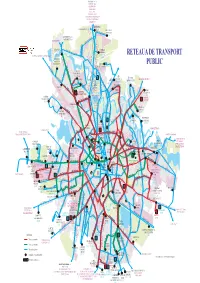

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

Halele Carol, Bucharest Observatory Case

8. Halele Carol (Bucharest, Romania) This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776766 Space for Logos H2020 PROJECT Grant Agreement No 776766 Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re- Project Full Title use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment Project Acronym OpenHeritage Grant Agreement No. 776766 Coordinator Metropolitan Research Institute (MRI) Project duration June 2018 – May 2021 (48 months) Project website www.openheritage.eu Work Package No. 2 Deliverable D2.2 Individual report on the Observatory Cases Delivery Date 30.11.2019 Author(s) Alina, Tomescu (Eurodite) Joep, de Roo; Meta, van Drunen; Cristiana, Stoian; Contributor(s) (Eurodite); Constantin, Goagea (Zeppelin); Reviewer(s) (if applicable) Public (PU) X Dissemination level: Confidential, only for members of the consortium (CO) This document has been prepared in the framework of the European project OpenHeritage – Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re-use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776766. The sole responsibility for the content of this document lies with the authors. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Deliverable -

Planul Integrat De Dezvoltare Urbana (Pidu)

Bucharest Central Area Integrated Urban Development Plan 1. Recovering the urban identity for the Central area. Today, for many inhabitants, the historic center means only the Lipscani area, which is a simplification of history. We are trying to revitalize and reconnect the different areas which constitute the center of Bucharest, from Victory Square to Carol Park, having the quality of urban life for city residents as a priority and trying to create a city brand for tourists and investors. 2. Recovering the central area located south of the Dambovita river. Almost a quarter of surveyed Bucharest residents had not heard of areas like Antim or Uranus, a result of the brutal urban interventions of the 1980s when, after intense demolitions, fragments of the old town have become enclaves hidden behind the high- rise communist buildings. Bridges over Dambovita disappeared, and whole areas south of the river are now lifeless. We want to reconnect the torn urban tissue and redefine the area located south of Dambovita. recover this part of town by building pedestrian bridges over the river and reconstituting the old ways of Rahovei and Uranus streets as a pedestrian and bicycle priority route. 3. Model of sustainable alternative transportation. Traffic is a major problem for the Bucharest city center. The center should not be a transit area through Bucharest and by encouraging the development of rings and the outside belt, car traffic in the downtown area can easily decrease. We should prioritize alternative forms of transportation - for decades used on a regular basis by most European cities: improve transportation connections and establish a network of streets with priority for cyclists and pedestrians to cross the Center. -

6. Public Transport

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects. A. Rapid assessment of the current situation Section 4. Mobility and Transport March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (47 Regina Elisabeta Blvd., Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Vasile Lascăr Street 31, FL. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 20221 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development on March 4, 2019. It is part of Output 3 under the above-mentioned agreement – Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects – under Component 1, which refers to the elaboration of Bucharest’s Integrated Urban Development Strategy, Capital Investment Planning and Management. -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Pipera Neighborhood

www.ssoar.info Pipera Neighborhood - Voluntari City (Romania): problems regarding inconsistency between the residential dynamic and the street network evolution between 2002 and 2011 COSTACHE Romulus; TUDOSE Ionuț Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: COSTACHE Romulus, & TUDOSE Ionuț (2012). Pipera Neighborhood - Voluntari City (Romania): problems regarding inconsistency between the residential dynamic and the street network evolution between 2002 and 2011. Cinq Continents, 2(6), 201-215. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-325228 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Volume 2 / Numéro 6 Hivér 2012 ISSN: 2247 - 2290 p. 201-215 PIPERA NEIGHBOURHOOD - VOLUNTARI CITY. PROBLEMS REGARDING INCONSISTENCY BETWEEN THE RESIDENTIAL DYNAMIC AND THE STREET NETWORK EVOLUTION BETWEEN 2002 AND 2011 Romulus COSTACHE Ionuț TUDOSE Master Std. Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest [email protected] Contents: 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Braukšanas Ierobežojumi Kravas Transportlīdzekļiem Rumānijā 2018. Gadā

Braukšanas ierobežojumi kravas transportlīdzekļiem Rumānijā 2018. gadā Vispārējie ierobežojumi: Transportlīdzekļi: Kravas transportlīdzekļi ar pilnu masu virs 7.5t; Ierobežojumu darbības zona: DN1, km 17 + 900 (Otopeni pilsētas robeža) – Ploiesti (krustojums DN1 –DN1A); Ierobežojumi spēkā: No 2018. gada 1. janvāra līdz 31. decembrim; Ierobežojumi spēkā Nr. Ceļš Ceļš Pirmdiena - Sestdiena - Piektdiena ceturtdiena svētdiena DN1, km 17 + 900 (Otopeni 1 pilsētas robeža) – Ploiesti (krustojums DN1 –DN1A) DN1 6.00 – 22.00 00.00 – 24.00 00.00 – 24.00 Ploiesti (krustojums DN1 –DN1B) 2 – Brasov (DN1 – DN1 A); Tabula nr.1 Izņēmumi: Civilās aizsardzības transportlīdzekļi, bēru transports, pirmās palīdzības un humanitārās palīdzības dienestu transportlīdzekļi, pasta pārvadājumi, degvielas pārvadājumi, specializētie avārijas transportlīdzekļi, sanitāro dienestu transportlīdzekļi. Alternatīvi maršruti: DN1A: Bucharest – Ploiesti – Brasov; A3: Bucharest – Ploiesti; DN1A: Ploiesti – Brasov; DN7: Bucharest – krustojums DN7 – DN71; DN71: krustojums DN7 – DN71 – Targoviste; DN72A: Targoviste – Stoenesti – krustojums DN72A – DN73; DN73: krustojums DN72A – DN73 – Rasnov – Brasov; Ierobežojumi vasarā Transportlīdzekļi: Kravas transportlīdzekļi ar pilnu masu virs 7.5t; Ierobežojumu darbības zona: skatīt “Tabula nr.2”; Ierobežojumi spēkā: Piektdienās, sestdienās un svētdienās, periodā no 2018. gada 1. jūlija līdz 2018. gada 31. augustam. *Uz A2 automaģistrāles braukšanas ierobežojumi attiecināmi uz kravas transportlīdzekļiem ar pilnu masu virs 3.5t. Ceļš Darbības -

Component 1. Elaboration of Bucharest's Iuds, Capital

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects. Chapter 3. Spatial and Functional Profile March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (Bd. Regina Elisabeta 47, Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Str. Vasile Lascăr 31, et. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 2021 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the -

The Revitalization of Bucharest's Center Surrounding Areas by Reconverting the Industrial Heritage Bîță, Claudiu

www.ssoar.info The revitalization of Bucharest's center surrounding areas by reconverting the industrial heritage Bîță, Claudiu Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bîță, C. (2017). The revitalization of Bucharest's center surrounding areas by reconverting the industrial heritage. Cinq Continents, 7(16), 192-225. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-63442-8 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Volume 7 / Numéro 16 Hiver 2017 ISSN: 2247 - 2290 p. 192-225 THE REVITALIZATION OF BUCHAREST’S CENTER SURROUNDING AREAS BY RECONVERTING THE INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE Claudiu BÎȚĂ Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest [email protected] Sommaire: 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................. 194 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS ......................................................................................................................... 196 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION .......................................................................................................................... -

CMN / EA International Provider Network HOSPITALS/CLINICS

CMN / EA International Provider Network HOSPITALS/CLINICS As of March 2010 The following document is a list of current providers. The CMN/EA International Provider Network spans approximately 200 countries and territories worldwide with over 2000 hospitals and clinics and over 6000 physicians. *Please note that the physician network is comprised of private practices, as well as physicians affiliated with our network of hospitals and clinics. Prior to seeking treatment, Members must call HCCMIS at 1-800-605-2282 or 1-317-262-2132. A designated member of the Case Management team will coordinate all healthcare services and ensure that direct billing arrangements are in place. Please note that although a Provider may not appear on this list, it does not necessarily mean that direct billing cannot be arranged. In case of uncertainty, it is advised Members call HCCMIS. CMN/EA reserves the right, without notice, to update the International Provider Network CMN/EA International Provider Network INTERNATIONAL PROVIDERS: HOSPITALS/CLINICS FacilitY Name CitY ADDRess Phone NUMBERS AFGHanistan DK-GERman MedicaL DiagnOstic STReet 66 / HOUse 138 / distRict 4 KABUL T: +93 (0) 799 13 62 10 CenteR ZOne1 ALBania T: +355 36 21 21 SURgicaL HOspitaL FOR ADULts TIRana F: +355 36 36 44 T: +355 36 21 21 HOspitaL OF InteRnaL Diseases TIRana F: +355 36 36 44 T: +355 36 21 21 PaediatRic HOspitaL TIRana F: +355 36 36 44 ALGERia 4 LOT. ALLIOULA FOdiL T: +213 (21) 36 28 28 CLiniQUE ChahRAZed ALgeR CHÉRaga F: +213 (21) 36 14 14 4 DJenane AchaBOU CLiniQUE AL AZhaR ALgeR -

Evaluation of Bucharest Soil Liquefaction Potential

Mathematical Modelling in Civil Engineering Vol. 11‐No. 1: 40‐48 – 2015 Doi: 10.1515/mmce‐2015‐0005 EVALUATION OF BUCHAREST SOIL LIQUEFACTION POTENTIAL ARION CRISTIAN - Lecturer, PhD, Technical University of Civil Engineering, e-mail: [email protected] CALARASU ELENA –Researcher, PhD, URBAN-INCERC Bucharest NEAGU CRISTIAN – Researcher, PhD Student, Technical University of Civil Engineering, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The paper contains the experimental research performed in Bucharest like the borehole data (Standard Penetration Test) and the data obtained from seismic investigations (down-hole prospecting and surface-wave methods). The evaluation of the soils liquefaction resistance based on the results of the SPT, down-hole prospecting and surface-wave method tests and the use of the earthquake records will be presented. Keywords: Bucharest, liquefaction, SPT, seismic prospecting 1. Introduction The Bucharest metropolitan area is located in the Romanian Plain, along the Colentina and Dambovita rivers, in the central part of the Moesian Sub-plate (age: Precambrian and Paleozoic). Over Cretaceous and Miocene deposits (having the top at about 1000 m depth) a Pliocene shallow water deposit (~700m thick) was settled. The surface geology consists mainly of Quaternary alluvial deposits with distinct peculiarities and large intervals of thickness characterize the city of Bucharest. Later loess covered these deposits and rivers shaped the present landscape [1]. The main source of earthquakes for Bucharest is the Vrancea seismic zone. When strong ground motions were recorded, they provided instrumental proofs of site effects. Site effects were firstly observed on the basis of damage pattern within the city. The borehole data and the experimental research performed in the last years revealed a new series of elements regarding the stratification and soil characteristics and of the long predominant period of soil vibration that characterize Bucharest [2]. -

Dismantling the Ottoman Heritage? the Evolution of Bucharest in the Nineteenth Century

Dismantling the Ottoman Heritage? The Evolution of Bucharest in the Nineteenth Century Emanuela Costantini Wallachia was part of the Ottoman Empire for nearly four centuries. Together with Moldova, the other Danubian principality, it maintained strong autonomy, as well as its own institutions, such as the position of voivoda (prince). The particular position of Wallachia in the Ottoman Empire is reflected by the peculiar aspect of Bucharest in the early nineteenth century. The Romanian scholars who studied the history of Bucharest, Ionescu-Gion and Pippidi, did not call it an Ottoman town. Maurice Cerasi, author of a very important study of Ottoman towns,1 has another viewpoint, and actually locates Bucharest at the boundaries of the Ottoman area. This means that Bucharest is not frequently taken as an example of typical Ottoman towns, but is sometimes mentioned as sharing some features with them. The evolution of Bucharest is one of the best instances of the ambiguous relationship existing between the Romanian lands and the Ottoman Empire. Moldova and Wallachia lacked the most evident expressions of Ottoman rule: there were no mosques, no Muslims, no timar system was implemented in these areas. But, on a less evident but deeper level, local culture and local society were rooted in the Ottoman way of life and displayed some of its main features: the absence of a centralized bureaucracy, the strong influence of the Greek commercial and bureaucratic elite of the Ottoman Empire, the phanariotes2 and a productive system based on agriculture and linked to the Ottoman state through a monopoly on trade. Bucharest was an example of this complex relationship: although it was not an Ottoman town, it shared many aspects with towns in the Ottoman area of influence.