(C) David Prutchi, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photographing Fluorescent Minerals with Mineralight and Blak-Ray

Application Bulletin UVP-AB-120 Corporate Headquarters: UVP, Inc. European Operations: Ultra-Violet Products Limited 2066 W. 11th Street, Upland, CA 91786 USA Unit 1, Trinity Hall Farm Estate, Nuffield Road Telephone: (800)452-6788 or (909)946-3197 Cambridge CB4 1TG UK Telephone: 44(0)1223-420022 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] PHOTOGRAPHING FLUORESCENT MINERALS WITH MINERALIGHT AND BLAK-R AY LAMPS Taking pictures in ultraviolet light of fluorescent minerals is a relatively simple operation if one follows certain basic requirements and understands the several variables that control what is obtained on the picture. There are several factors that control obtaining the best picture and among these are the size of power of the ultraviolet light source, the distance of the light source to the subject, the type of film used, the fluorescent color of the mineral specimen, the type of filter on the camera, and the final exposure of the picture. These subjects are taken up below in orde r. The size of the light source will make a difference as far as the picture is concerned because the more powerful the light source, the shorter the exposure. The distance of the ultraviolet light to the subject is also of great importance for the closer the light source is to the subject being photographed, the brighter the fluorescence will be and the shorter exposure required. While tubular light sources do not vary according to the so-called square la w, never- theless, moving the light source into one-half of its original distance will more than double the light intensity with corresponding increase in fluorescent brightness. -

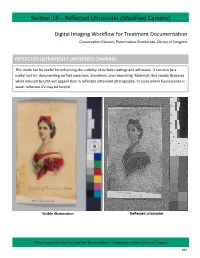

Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera)

Section 18—Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera) Digital Imaging Workflow for Treatment Documentation Conservation Division, Preservation Directorate, Library of Congress REFLECTED ULTRAVIOLET (MODIFIED CAMERA) This mode can be useful for enhancing the visibility of surface coatings and adhesives. It can also be a useful tool for documenting surface abrasions, accretions, and retouching. Materials that visably fluoresce when induced by UVA will appear dark in reflected ultraviolet photography. In cases where fluorescence is weak, reflected UV may be helpful. Visible illumination Reflected ultraviolet Digital Imaging Workflow for Treatment Documentation—Conservation Division, Library of Congress 18.1 Section 18—Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera) Figure 18.01 Figure 18.02 Figure 18.03 Digital Imaging Workflow for Treatment Documentation—Conservation Division, Library of Congress 18.2 Section 18—Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera) Capture Preliminary If not done already, capture a visible illumination image with the modified camera following instructions in Section 14. Wear UV goggles when the UV lights are on. Set Up 1. Use the Nikon D700 modified camera and the CoastalOpt lens. 2. The CoastalOpt lens MUST be set at the minimum aperture setting of f/45 to utilize the electronic aperture function (otherwise the camera will display FEE). 3. The PECA 900 and X-Nite BP1 filters are used for reflected ultraviolet photography with the modified camera (fig 18.01). The filters are stored in the studio cabinet. Very carefully, screw on both filters to the end of the camera lens. The order the filters are screwed on does not matter. 4. Plug in the UV lamps. It is important to plug in both cords (two for each lamp) for at least 20 seconds before switching on lamps. -

Introduction to Photography

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Introduction to Photography Study Material for Students : Introduction to Photography CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. It functions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news Edited with the trial version of editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman,Foxit Advanced producer, PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: director, etc. www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 : Introduction to Photography INTRODUCTION The book will introduce the student to the techniques of photography. The book deals with the basic steps in photography. Students will also learn the different types of photography. The book also focuses of the various parts of a photographic camera and the various tools of photography. Students will learn the art of taking a good picture. The book also has introduction to photojournalism and the basic steps of film Edited with the trial version of development in photography. -

Redalyc.Technical Photography for Mural Paintings: the Newly

Conservar Património E-ISSN: 2182-9942 [email protected] Associação Profissional de Conservadores Restauradores de Portugal Portugal Cosentino, A.; Gil, M.; Ribeiro, M.; Di Mauro, R. Technical photography for mural paintings: the newly discovered frescoes in Aci Sant’Antonio (Sicily, Italy) Conservar Património, núm. 20, diciembre, 2014, pp. 23-33 Associação Profissional de Conservadores Restauradores de Portugal Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=513651365003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Article / Artigo Technical photography for mural paintings: the newly discovered frescoes in Aci Sant’Antonio (Sicily, Italy) A. Cosentino1,* M. Gil2 M. Ribeiro3 R. Di Mauro4 1 Cultural Heritage Science Open Source, Piazza Cantarella, 11 Aci Sant’Antonio, 95025, Italy 2 Hercules Laboratory, Évora University, Palácio do Vimioso 8, 7000-809 Évora, Portugal 3 Professional photographer ( freelancer) 4 Professional architect (freelancer) * [email protected] Abstract Keywords A cycle of 18th century frescoes, depicting the last days of Christ on earth, were recently discovered Panoramic photography in Aci Sant’Antonio (Sicily, Italy). The paintings survive along the corners of an originally square Infrared photography chapel that was altered in the early 20th century, acquiring the current octagonal plan. This Ultraviolet photography paper presents the results of the technical photography documentation of these wall paintings Raking light photography and illustrates the methodological challenges that were posed during their examination. Raking Infrared false color light photography was used to reveal the paintings’ state of conservation, details of the plaster Mural paintings work and painting techniques. -

Effects of Light on Materials in Collections

Effects of Light Effects on Materials in Collections Data on Photoflash and Related Sources Schaeffer T. Terry The Getty Conservation Institute research in conservation GCI Effects of Light on Materials in Collections Schaeffer research in conservation The Getty Conservation Institute Effects of Light on Materials in Collections Data on Photoflash and Related Sources Terry T. Schaeffer 2001 Dinah Berland: Editorial Project Manager Elizabeth Maggio: Manuscript Editor Anita Keys: Production Coordinator Hespenheide Design: Designer Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 © 2001 The J. Paul Getty Trust Second printing 2002 Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049–1682 www.getty.edu The Getty Conservation Institute The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance conservation in the visual arts. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, model field projects, and the dissemination of information. The Institute is a program of the J. Paul Getty Trust, an international cultural and philanthropic institution devoted to the visual arts and the humanities. Research in Conservation The Research in Conservation reference series presents the findings of research conducted by the Getty Conservation Institute and its individual and institutional research partners, as well as state-of-the-art reviews of conservation literature. Each volume covers a topic of current interest to conservators and conservation scientists. Other volumes in the Research in Conservation series include Biodeterioration of Stone in Tropical Environments: An Overview (Kumar and Kumar 1999); Inert Gases in the Control of Museum Insect Pests (Selwitz and Maekawa 1998); Oxygen-Free Museum Cases (Maekawa 1998); Accelerated Aging: Photochemical and Thermal Aspects (Feller 1994); Airborne Particles in Museums (Nazaroff, Ligoki, et al. -

UV and IR Photography

UV & IR PHOTOGRAPHY IN FORENSIC SCIENCE INTRODUCTION • Ultraviolet and infrared have valuable application in law enforcement photography. • Photography utilizing these radiations may provide information about an object or material which cannot be obtained by other photographic methods. Either or both could be considered as part of a physical examination in cases where visual examination or photography by normal processes fail. • The visible spectrum ranges from blue at 400nm to red at 700nm.Ultraviolet wavelengths are shorter than 400nm and infrared wavelengths are longer than 700nm. • They provide us with no visual response and therefore are not considered to be light. Certain narrow bands of this invisible radiation, however, have practical photographic applications. • All standard photographic papers and photographic films are sensitive to UV. They are not, however, sensitive to infrared. Special film, sensitized to infrared radiations, is required for infrared photography. This infrared film is also sensitive to blue-violet and to ultraviolet. • Developing and printing techniques are similar to the normal processes for both ultraviolet and infrared photography. • The good thing is that both processes are non- destructive to inanimate objects. For life forms, the usual precautions regarding exposure to the eyes should be heeded. In cases of uncertainty as to which technique might produce the best results, you may have to try all. ULTRAVIOLET PHOTOGRAPHY • Ultraviolet Radiation • For practical photographic purposes we use only the long wave ultraviolet band. • Long wave ultraviolet :- 320 to 400 nanometres. • This band is transmitted by regular optical glass, of which most photographic lenses are made and, therefore, is of most practical value in ultraviolet photography. -

Infrared Photography Andrew Davidhazy Rochester Institute of Technology

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Articles 1993 Infrared Photography Andrew Davidhazy Rochester Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/article Recommended Citation Davidhazy, Andrew. "Infrared Photography." The ocalF Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition, edited by Leslie Stroebel and Richard Zakia, Focal Press, 1993, pp. 389-395. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFRARED PHOTOGRAPHY Andrew Davidhazy Imaging and Photographic Technology Department School of Photographic Arts and Sciences Rochester Institute of Technology (this material was prepared for Focal Encyclopedia of Photography) Infrared photography is of interest to the amateur and commercial photographer and to scientists and technologists because it produces images that are not possible with conventional photographic films. In its practice there is not much difference between infrared and normal photography. The same cameras and light sources can usually be used, together with the same processing solutions. Infrared photography, however, is usually only attempted by skilled photographers, scientists, and technicians with a particular purpose in mind. Technique The peculiarities of infrared photography lie in the ability of the film to record what the eye cannot see (permitting, for instance, photography in the dark); in the fact that many materials reflect and transmit infrared radiation in a different manner than visible radiation (light); in the ability of infrared radiation to penetrate certain kinds of haze in the air so that photographs can be taken of distant objects that cannot be seen or photographed on normal films; and in the ability to photograph hot objects by the long- wavelength radiation that they emit. -

Michelle Sullivan, Shannon Brogdon-Grantham, and Kimi Taira Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation

Michelle Sullivan, Shannon Brogdon-Grantham, and Kimi Taira Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation New Approaches to Cleaning Works of Art on Paper and Photographs Sullivan et al., ANAGPIC 2014, 2 ABSTRACT During the Fall 2013 semester, second-year graduate students in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation completed a course entitled “Conservation Cleaning Methods” led by Professor Richard Wolbers. This course explored approaches to controlled cleaning of works of art and artifacts using gels, microemulsions, and silicone solvents, as well as the optimization of aqueous cleaning systems through pH-adjustment and the addition of chelators, enzymes, and surfactants. This paper discusses two studies undertaken by students specializing in the conservation of works on paper and photographic materials as an extension of this course and in collaboration with scientists and conservators at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library to address specific problems within their disciplines. The first study explored the reduction of foxing stains in paper-based materials utilizing a combined chelator-enzyme solution delivered locally using rigid gels. As the exact nature of foxing remains an area of debate among conservators and scientists, students first demonstrated that the phenomenon related to both metal oxidation and biological growth in paper samples used in this experiment. Foxed samples were subjected to a histological staining protocol to confirm the presence of fungi, and x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) was performed to determine the relative metal concentration in affected areas. With the source of foxing established, an experiment was devised to explore the combined and independent treatment effects of the chelator hydroxybenzyl ethylenediamine (HBED), the enzyme chitinase, and the rigid agarose gel. -

The Ultraviolet Photography of Nature: Techniques, Material and (Especially) Lacertini Results

Butll. Soc. Cat. Herp., 20 (2012) The Ultraviolet Photography of Nature: Techniques, Material and (especially) Lacertini results Oscar J. Arribas Avgda. Fc. Cambó 23; 08003 Barcelona (SPAIN). Email: [email protected] Abstract In this paper we deal on the ultraviolet color (invisible to us): where we can find it, the capability of animals to see it and the advantages that this color perception offers to them. As the simplest way to detect it is the photography, we describe and review how to photograph the UV, as a result of 15 years of amateur experience, searching and testing nearly in complete blindness due to the lack of practical information about “how to do it”. We describe the different kinds of photography (chemical and digital); the cameras and objectives suitable (both astronomically expensive ones and cheap options); what are the best characteristics that the objectives should have for this purpose; the films suitable for their use in chemical photography; the different filters (current or discontinued) manufactured along the years; and the subtle combinations among the different materials to obtain pure UV photographs. This kind of scientific photography is mainly used in forensics, forgery detection, art dermatology and less in Natural History, despite the fact that a great part of animals see this color and use it in important questions of their biology as the social behavior, mate choice or the food search. Resum Aquest article tracta sobre el color ultraviolat (invisible pels Éssers Humans): on és present i la capacitat dels animals per veure-ho. Com que la manera més senzilla per detectar-lo es mitjançant la fotografia, descric i repasso com fotografiar l’UV, com a fruit de la experiència de 15 anys de proves pràcticament des de zero. -

Uv) Photography to Visualize Hidden Characters on the Wings of Lepidoptera (E.G

210 JOU RNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTElIISTS' SOCIETY ULTRAVIOLET PHOTOGRAPHY AS AN ADJUNCT TO TAXONOMYl CLIFFORD D. FERRIS2 College of Engineering, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming 82070 Several papers have been published on the use of ultraviolet (uv) photography to visualize hidden characters on the wings of Lepidoptera (e.g. Nekrutenko, 1964, 1965; Eisner et al., 1969). These hidden patterns probably relate to differing characteristics of the scales and their arrange ment on the wings. Some work has been carried out using a scanning electron microscope to detect differences in scale characteristics (Kolyer & Reimschuessel, 1969). Most of the more recently published papers have treated the Coliadinae, especially the genus Gonepteryx. In this subfamily, luminous patches appear on the dorsal surfaces of the wings when they are photographed under ultraviolet light. In other genera, Papilio for example, forms which appear quite different when viewed under white light appear nearly identical whcn photographed under uv light. Photographic techniques are necessary to visualize the ultraviolet evoked patterns as the human eye does not respond to that pOltion of the electromagnetic spectrum. From analysis of black light response in Lepidoptera, their visual perception ranges seem to peak in the range .300-400 nanometers (millimicrons). Since most of the readily available literature on ultraviolet photography of insects does not give details of technique, it is felt that a technique should be described which could be applied by anyone with a basic knowledge of photography. That is the purpose of this paper. The primary prerequisite is a camera which has a lens that will pass uv. Generally the better quality modern 35 mm single-lens-reflex cameras from Germany and Japan meet this criterion. -

Overview of Infrared and Ultraviolet Photography

Overview of Infrared and Ultraviolet Photography Theory, Techniques and Practice Andrew Davidhazy School of Photographic Arts and Sciences Rochester Institute of Technology The following pages are the textual reproduction of a traditional slide presentation with the associ- ated annotations for each image as if the material was presented “live”. Along with a general introduction to the theory and practice of photography by invisible radiaton among these slides you will also find references to practical applications of the various techniques available to the industrial, technical, forensic or creative photographer. The material also can be used as a tutorial on the subject of infrared and ultraviolet photography and associated techniques. Hopefully you will find this material interesting and informative. Before getting started with the rest of the material I’d like to mention that this presentation will not cover certain topics that are related in general terms to the main topic that we are concerned with. Photography is primarily concerned with an accurate representation of subject colors. However, variations in color repro- duction can be achieved by constructing emulsions that assign other than proper dye layers to the various colors present in a scene. These would be called “false color” reproductions. This is exemplified by the image seen here. It was made with color infrared film. This kind of film or emul- sion is sensitive to red, green and blue and also in- frared. The sensitivity to blue is essentially eliminated by photographing through a yellow filter and thus the three emulsion layers are now sensitive to green, red and infrared and these control the cyan, magenta and yellow dyes formed in the film as a result of exposure. -

Vernacular Photographic Genres After the Camera Phone

Natalia Rulyova and Garin Dowd, Genre Trajectories, 2015, Palgrave Macmillan reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan. This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: http://www.palgraveconnect.com/pc/doifinder/10.1057/9781137505484 . 1 8 Vernacular photographic genres after the camera phone Peter Buse I What is the place of photography in a book on genre? Genre theory, as Garin Dowd notes, has played a ‘minor role…in the areas of the musical, visual, and plastic arts’, with the most fertile ground found in literary studies. (Dowd, 2006, p.21) In genre studies, visual culture is nonetheless prominent, but mainly in its narrative-based forms, such as cinema and television. John Frow, in his introduction to genre, cites as relevant the following visual or plastic arts: drawing, painting, sculpture, architecture, film, television, opera, drama; but does not mention photography. (Frow, 2006, p.1) In photography studies meanwhile, genre is neither a key category of analysis nor subject to extensive theorisation. Photography critics usually call their object a medium or consider it primarily a technology with specific properties, a distinction behind which many controversies rage. In the key volume Photography Theory, for example, central figures in photography studies lock horns and come to a stalemate over issues such as ‘medium specificity’ and photography’s ‘indexicality’. (Elkins, 2007, pp.183-96 and pp.256-69) Nowhere in this dispute does genre raise its head. The parameters for this exclusion of generic questions were perhaps set in 1961 when Roland Barthes characterized photography as ‘a message without a code’, ‘a mechanical analogue of reality’ (Barthes, 1977, pp.17-8).