Vernacular Photographic Genres After the Camera Phone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History

e “Unruly, energetic, unmastered. Also erudite, engaged and rigorous. Batchen’s essays have arrived at exactly the e a c h w i l d i d e a right moment, when we need their skepticism and imagination to clarify the blurry visual thinking of our con- a writing photography history temporary cultures.” geoffrey batchen c —Ross Gibson, Creative Director, Australian Centre for the Moving Image h In Each Wild Idea, Geoffrey Batchen explores widely ranging “In this remarkable book, Geoffrey Batchen picks up some of the threads of modernity entangled and ruptured aspects of photography, from the timing of photography’s by the impact of digitization and weaves a compelling new tapestry. Blending conceptual originality, critical invention to the various implications of cyberculture. Along w insight and historical rigor, these essays demand the attention of all those concerned with photography in par- the way, he reflects on contemporary art photography, the role ticular and visual culture in general.” i of the vernacular in photography’s history, and the —Nicholas Mirzoeff, Art History and Comparative Studies, SUNY Stony Brook l Australianness of Australian photography. “Geoffrey Batchen is one of the few photography critics equally adept at historical investigation and philosophi- d The essays all focus on a consideration of specific pho- cal analysis. His wide-ranging essays are always insightful and rewarding.” tographs—from a humble combination of baby photos and —Mary Warner Marien, Department of Fine Arts, Syracuse University i bronzed booties to a masterwork by Alfred Stieglitz. Although d Batchen views each photograph within the context of broader “This book includes the most important essays by Geoffrey Batchen and therefore is a must-have for every schol- social and political forces, he also engages its own distinctive ar in the fields of photographic history and theory. -

Destruction and Transformation Vernacular Photography and the Built Environment

Destruction and Transformation Vernacular Photography and the Built Environment February 8 – May 25, 2019 Unidentified photographer, [Building Implosion, Stowers Furniture Company, San Antonio, TX], 1981. Courtesy The Walther Collection. Opening Reception: Thursday, February 7, from 6 – 8pm The Walther Collection Project Space 526 West 26th Street, Suite 718 New York, NY 10001 +1 212 352 0683 | [email protected] The Walther Collection is pleased to present Destruction and Transformation: Vernacular Photography and the Built Environment, an exhibition that examines the decisive role of vernacular photography in capturing the convulsive cycles of change that define modernist topographies. Since the nineteenth century, engineers, city planners, architects, industrialists, and tourists have used photography to record and promote metropolitanism: a global affirmation of modern urban expansion, often at the expense of natural ecology, historic structures, or existing populations. The sixteen photographic series in this exhibition, spanning from 1876 to 2000, depict the inescapable obsolescence of urban and industrial projects, often traversing, partitioning, and exploiting the natural environment. These pictures together provide a counternarrative to the presupposed stability of aesthetic and structural planning within modernist city spaces and architecture. Photographic documentation has often been crucial to establishing the progress of consumption and destruction of land and to justifying the outcomes of such efforts for a larger public—or to lamenting its effects retrospectively. This exhibition proposes two paradigmatic sites as case studies: the Appalachian coalfields, where the extraction of fossil fuels has required the reshaping of the natural landscape and the local social organization; and New York City, where an unceasing cycle of destruction and construction drives modern urban development. -

Penelope Umbrico's Suns Sunsets from Flickr

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Image Commodification and Image Recycling: Penelope Umbrico's Suns Sunsets from Flickr Minjung “Minny” Lee CUNY City College of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/506 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Image Commodification and Image Recycling: Penelope Umbrico’s Suns from Sunsets from Flickr Submitted to the Faculty of the Division of the Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and Liberal Arts by Minjung “Minny” Lee New York, New York May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Minjung “Minny” Lee All rights reserved CONTENTS Acknowledgements v List of Illustrations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1. Umbrico’s Transformation of Vernacular Visions Found on Flickr 14 Suns from Sunsets from Flickr and the Flickr Website 14 Working Methods for Suns from Sunsets from Flickr 21 Changing Titles 24 Exhibition Installation 25 Dissemination of Work 28 The Temporality and Mortality of Umbrico’s Work 29 Universality vs. Individuality and The Expanded Role of Photographers 31 The New Way of Image-making: Being an Editor or a Curator of Found Photos 33 Chapter 2. The Ephemerality of Digital Photography 36 The Meaning and the Role of JPEG 37 Digital Photographs as Data 40 The Aura of Digital Photography 44 Photography as a Tool for Experiencing 49 Image Production vs. -

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine by Meryem Kamil A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Evelyn Alsultany, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Nakamura, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Anna Watkins Fisher Professor Nadine Naber, University of Illinois, Chicago Meryem Kamil [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2355-2839 © Meryem Kamil 2019 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support and guidance of many, particularly my family and Kajol. The staff at the American Culture Department at the University of Michigan have also worked tirelessly to make sure I was funded, healthy, and happy, particularly Mary Freiman, Judith Gray, Marlene Moore, and Tammy Zill. My committee members Evelyn Alsultany, Anna Watkins Fisher, Nadine Naber, and Lisa Nakamura have provided the gentle but firm push to complete this project and succeed in academia while demonstrating a commitment to justice outside of the ivory tower. Various additional faculty have also provided kind words and care, including Charlotte Karem Albrecht, Irina Aristarkhova, Steph Berrey, William Calvo-Quiros, Amy Sara Carroll, Maria Cotera, Matthew Countryman, Manan Desai, Colin Gunckel, Silvia Lindtner, Richard Meisler, Victor Mendoza, Dahlia Petrus, and Matthew Stiffler. My cohort of Dominic Garzonio, Joseph Gaudet, Peggy Lee, Michael -

D100 Reviews

D100 Feb 2002 - Jun 2003 Digital Photo Techniques May/June 2003 In this review by Stephen Brown, he found the D100 to have accessible controls, fit easily in his hand and produces extraordinary images. Brown stated, “The D100 is Nikon’s answer to serious photographers.” He was impressed with the wide range of color capture options, durability and found the D100 to be “the perfect camera for anyone transitioning into digital.” The Washington Times December 2002 In his review of the Nikon D100, Mark Kellner stated, “Nikon’s D100 makes me want to be a better shutterbug.”Kellner points out that the D100 produces high quality images and has a compact, lightweight design that fits easily into ones hand. Electronic Publishing December 2002 In this review by Ira Gold, he found the D100 to have a great ability to control white balance, fit easily into his hand, and stated “If I were to design my ideal camera, it would look a lot like the D100.” He was impressed with the D100’s high image quality, was easy to navigate controls and compatibility with Nikon’s interchangeable Nikkor lenses. American Photo November/December 2002 In his review of the Nikon D100, Jonathan Barkey points out that the D100 has high image quality, easy to navigate controls, is lightweight, and compatible with Nikon’s interchangeable Nikkor lenses. Barkey was impressed the D100 and said, “The camera is a pleasure to use – with both wonderful handling and top-notch image quality.” Time.com November 2002 In this review of the D100, Wilson Rothman found the camera to have “astounding” picture quality, with easy to navigate controls, similar to Nikon’s film cameras. -

Los Gatos-Saratoga Camera Club

LGSCC Camera Club losgatos–saratogacameraclub.org Volume 42 Issue 11 ► November 2020 In this issue Notices and Coming Events • November meeting to be online – Covid-19 Issue 8 See the Calendar on our web site for updates or details. • 1st place winners from October tell their stories Mon. November 2nd, Competition - Travel/PJ • 2020 Audubon Photo Awards 7:30 p.m. See deadlines and more info on the website • Adobe MAX roundup - What you missed • October 19th Critique and 22nd Photographer Program • Is modern landscape photography fake? • Free Matt Kloskowski webcast learning • Memoriam - Bill Ray • Information/Education Next Competition - Travel/PJ November 2nd Judge for October 5th will be Ian Bornarth. From his LinkedIn- “I create stock photography and fine art images of subjects including lifestyle, sports, nature and Previous PhotoJournalism image landscape. I occasionally provide photography workshops in the northern California area. www.ianbornarth.com Announcements Travel - A travel photograph must express the feeling of Meeting November 2nd will be virtual. a time and place, portray a land, its people or a culture in Check your email soon for link and full details. its natural state, and has no geographic limitations. Ultra A few points: close-ups which lose their identity, studio-type model shots, • Attendance will be via Zoom meetings or photographic manipulations which misrepresent the true • Categories – Travel, PJ, Color, and Mono situation or alter the content of the image are unacceptable • Submit images same as usual (projected only) in Travel competition. Images from events or activities arranged specifically for photography, or of subjects • You can submit up to 2 projected images directed or hired for photography are not permitted. -

Early African American Photography

In a New Light 7 Review Essay In a New Light: Early African American Photography Tanya Sheehan THE CAMERA AND THE PRESS: American Visual and Print Culture in the Age of the Daguerreotype. By Marcy J. Dinius. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 2012. PICTURES AND PROGRESS: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity. Edited by Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith. Durham: Duke University Press. 2012. EMBODYING BLACK EXPERIENCE: Stillness, Critical Memory, and the Black Body. By Harvey Young. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 2010. DELIA’S TEARS: Race, Science, and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2010. In 2000, art historian, curator, and artist Deborah Willis presented Reflections in Black, the first major history of photography in the United States to foreground early African American photography. In the three years that the exhibition toured 0026-3079/2013/5203-007$2.50/0 American Studies, 52:3 (2013): 007-024 7 8 Tanya Sheehan the country, and in the decade that its catalogue has been read avidly by students, historians, and practitioners of photography, Reflections in Black has exercised a powerful influence on how we think about photographic self-representation within the African American community. Willis taught us how to look for and at images that did not grossly caricature black bodies but instead “celebrated the achievements” of black subjects and “conveyed a sense of self and self-worth” (Willis, xvii). The placement of cameras in black hands, she argued, made such counter-representation possible; writing a different history of African American life and culture therefore depended on rediscovering the first black photogra- phers. -

Making Sense of the Selfie: Keywords: Rudolfs Blaumanis, Gottfried Keller, 19Th Century Literature, Latvian Litera Ture, Autobiographical Novel, Art and Artist

46 RAKSTI BENEDIKTS KALNACS 47 Artist. Reality, and (Auto)biography ALISE TIFENTALE in Rudolfs Blaumanis's and Gottfried Keller's Fiction Making Sense of the Selfie: Keywords: Rudolfs Blaumanis, Gottfried Keller, 19th century literature, Latvian litera ture, autobiographical novel, art and artist. Digital Image-Making Summary and Image-Sharing in Social Media The paper discusses aspects of the Latvian writer's Rudolfs Blaumanis (1863-1908) fiction in comparative perspective. An important aspect of Blaumanis's efforts was devoted to the discussion ofindividual life stories of his characters, and he also dealt with the possibility or impossibility of a person to become his or her true self in the interpretative contexts ofthe l 9th century society and culture. In European perspective, Keywords: History of photography, digital photography, social media, the image of an artist was often put at the centre of writers' attention, and the paper Ins tagram, self-portraits, software studies. provides one such case study, a discussion of the Swiss author's, Gottfried Keller autobiographical novel "Green Henry" (Der Grune Heinrich, 1st version 1855, 2nd Introduction version 1880) to which the works ofBlaumanis are then compared. The paper deals with some of the Latvian author's most important novellas, written between 1882 and 1898, A wide range of photographic practices has flo urished outside the and discusses the impossibility of artistic career in the context of the 19th century institutional framework of the art world or commercial photography since Latvian society due to different historical and social background as discussed in the early 1900s, when the availability and ease of use of the Kodak Brownie Blaumanis's texts. -

Photographing Fluorescent Minerals with Mineralight and Blak-Ray

Application Bulletin UVP-AB-120 Corporate Headquarters: UVP, Inc. European Operations: Ultra-Violet Products Limited 2066 W. 11th Street, Upland, CA 91786 USA Unit 1, Trinity Hall Farm Estate, Nuffield Road Telephone: (800)452-6788 or (909)946-3197 Cambridge CB4 1TG UK Telephone: 44(0)1223-420022 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] PHOTOGRAPHING FLUORESCENT MINERALS WITH MINERALIGHT AND BLAK-R AY LAMPS Taking pictures in ultraviolet light of fluorescent minerals is a relatively simple operation if one follows certain basic requirements and understands the several variables that control what is obtained on the picture. There are several factors that control obtaining the best picture and among these are the size of power of the ultraviolet light source, the distance of the light source to the subject, the type of film used, the fluorescent color of the mineral specimen, the type of filter on the camera, and the final exposure of the picture. These subjects are taken up below in orde r. The size of the light source will make a difference as far as the picture is concerned because the more powerful the light source, the shorter the exposure. The distance of the ultraviolet light to the subject is also of great importance for the closer the light source is to the subject being photographed, the brighter the fluorescence will be and the shorter exposure required. While tubular light sources do not vary according to the so-called square la w, never- theless, moving the light source into one-half of its original distance will more than double the light intensity with corresponding increase in fluorescent brightness. -

The Amateur Photographer Masterclass with Tom Mackie

Panoramas Masterclass LEARN FROM THE Burton Falls, a short distance away, and EXPERTS finally, if we have time, travel to Hardraw The Amateur Photographer Force, England’s largest single drop waterfall, which is great for vertical panoramas’. The following morning, as the rain lashed Masterclass with Tom Mackie down, a dawn shoot was out of the question, but the readers, huddled under umbrellas and undeterred, set out to capture some of North Yorkshire’s most majestic waterfalls. They had brought their own cameras, lenses, tripods and cable releases with them, and Tom was on hand to help them Panoramas set up their tripods and cameras, and share Tom Mackie shows three readers how to shoot his in-depth knowledge throughout the day. ‘While you don’t need a tripod with and stitch fantastic panoramic images in the an expensive panoramic head to create sweeping panoramas, a good-quality tripod, Yorkshire Dales. Gemma Padley joined them preferably with a ball head and spirit level on the tripod neck, is useful,’ says Tom. ‘You When photographing the landscape, Yorkshire Dales to try their hand at shooting may want to use an ND grad filter, but avoid it can be tricky fitting everything into the and stitching panoramic images. using a polariser when shooting the sky as the frame. Even using your widest focal length Tom met the readers the night before polarisation will vary. You could use a polariser there are situations in which it is impossible and discussed the plan for the following day The sweeping for the waterfalls [if there’s not much sky in to capture the scale of a place in a single over dinner. -

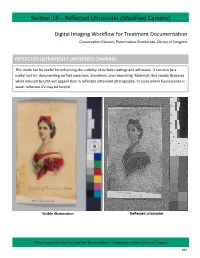

Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera)

Section 18—Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera) Digital Imaging Workflow for Treatment Documentation Conservation Division, Preservation Directorate, Library of Congress REFLECTED ULTRAVIOLET (MODIFIED CAMERA) This mode can be useful for enhancing the visibility of surface coatings and adhesives. It can also be a useful tool for documenting surface abrasions, accretions, and retouching. Materials that visably fluoresce when induced by UVA will appear dark in reflected ultraviolet photography. In cases where fluorescence is weak, reflected UV may be helpful. Visible illumination Reflected ultraviolet Digital Imaging Workflow for Treatment Documentation—Conservation Division, Library of Congress 18.1 Section 18—Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera) Figure 18.01 Figure 18.02 Figure 18.03 Digital Imaging Workflow for Treatment Documentation—Conservation Division, Library of Congress 18.2 Section 18—Reflected Ultraviolet (Modified Camera) Capture Preliminary If not done already, capture a visible illumination image with the modified camera following instructions in Section 14. Wear UV goggles when the UV lights are on. Set Up 1. Use the Nikon D700 modified camera and the CoastalOpt lens. 2. The CoastalOpt lens MUST be set at the minimum aperture setting of f/45 to utilize the electronic aperture function (otherwise the camera will display FEE). 3. The PECA 900 and X-Nite BP1 filters are used for reflected ultraviolet photography with the modified camera (fig 18.01). The filters are stored in the studio cabinet. Very carefully, screw on both filters to the end of the camera lens. The order the filters are screwed on does not matter. 4. Plug in the UV lamps. It is important to plug in both cords (two for each lamp) for at least 20 seconds before switching on lamps. -

Introduction to Photography

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Introduction to Photography Study Material for Students : Introduction to Photography CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. It functions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news Edited with the trial version of editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman,Foxit Advanced producer, PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: director, etc. www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 : Introduction to Photography INTRODUCTION The book will introduce the student to the techniques of photography. The book deals with the basic steps in photography. Students will also learn the different types of photography. The book also focuses of the various parts of a photographic camera and the various tools of photography. Students will learn the art of taking a good picture. The book also has introduction to photojournalism and the basic steps of film Edited with the trial version of development in photography.