Tex-Mex” Come From? the Divisive Emergence of a $ Social Category

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compact Deep Fryer CDF-100 for Your Safety and Continued Enjoyment of This Product, Always Read the Instruction Book Carefully Before Using

INSTRUCTION AND RECIPE BOOKLET Compact Deep Fryer CDF-100 For your safety and continued enjoyment of this product, always read the instruction book carefully before using. 15. Do not operate your appliance in an appliance garage or under a IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS wall cabinet. When storing in an appliance garage always unplug the unit from the electrical outlet. Not doing so could When using electrical appliances, basic safety precautions should create a risk of fire, especially if the appliance touches the walls of always be followed, including the following: the garage or the door touches the unit as it closes. 1. READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS. 2. Unplug from outlet when not in use and before cleaning. Allow appliance and the oil to cool completely before putting on or taking off parts, and before cleaning or draining the appliance. SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS 3. Do not touch hot surface; use handles or knobs. FOR HOUSEHOLD USE ONLY 4. To protect against electric shock, do not immerse cord, plug or base unit in water or other liquid. 5. Close supervision is necessary when any appliance is used by or near children. 6. Do not operate any appliance with a damaged cord or plug or SPECIAL CORD SET after an appliance malfunctions, or has been damaged in any manner. Return appliance to the nearest authorized service facility INSTRUCTIONS for examination, repair or adjustment. A short power supply cord is provided to reduce the risk of becoming 7. The use of accessory attachments not recommended by entangled in or tripping over a long cord. A longer detachable power- Cuisinart may cause injuries. -

T H E J a M E S B E a R D F O U N D a T I O N a W a R D S for IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2008 JAMES BEARD FOUNDATION AWARDS RESTAUR

http://www.jamesbeard.org/about/press/newsdetails.php?news_id=109 T h e J a m e s B e a r d F o u n d a t i o n A w a r d s FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contacts: James Curich / Jessica Cheng Susan Magrino Agency 212-957-3005 [email protected] / [email protected] 2008 JAMES BEARD FOUNDATION AWARDS RESTAURANT AND CHEF SEMIFINALIST NOMINEES NOW AVAILABLE FINAL NOMINATIONS TO BE ANNOUNCED ON MARCH 24, 2008 New York, NY (28 February 2008) - The list of Restaurant and Chef semifinalists for the 2008 James Beard Foundation Awards, the nation’s most prestigious honors for culinary professionals, is now available at www.jamesbeard.org. Selected from thousands of online entries, the prestigious group of semifinalists in the 19 Restaurant and Chef categories represents a wide variety of culinary talent, from legendary chefs and dining destinations in 10 different regions across the United States, to the nation’s best new restaurants and rising star chefs. On Monday, March 24, 2008, the James Beard Foundation will announce the final nominees – five in each category, narrowed down from the list of semifinalists by a panel of more than 400 judges – during an invitation-only press breakfast at the historic James Beard House in New York City’s West Village. The winners will be announced on Sunday, June 8, 2008 at the Awards Ceremony and Gala Reception, the highly-anticipated annual celebration taking place at Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center. The James Beard Foundation Awards is the nation’s preeminent recognition program honoring professionals in the food and beverage industries. -

Manual Para La Elaboración De Productos Derivados De La Leche Con Valor Agregado

Manual para la elaboración de productos derivados de la leche con valor agregado Luciano Pérez Valadez* César Óscar Mar nez Alvarado** *Centro de Validación y Transferencia de Tecnología de Sinaloa, A. C. **Fundación Produce Sinaloa, A. C. Í Introducción .....................................................................................7 Producción de leche en el sur de Sinaloa ..........................................8 Situación del mercado de la leche y sus derivados ............................ 9 Procesos para la elaboración de productos lácteos ........................... 11 Procedimiento para la elaboración de yogur .....................................11 Procedimiento para la elaboración de queso manchego ................... 13 Procedimiento para la elaboración de queso Oaxaca ........................ 15 Procedimiento para la elaboración de rompope ...............................17 Procedimiento para la elaboración de queso botanero ..................... 18 Procedimiento para la elaboración de jocoque ................................. 19 Procedimiento para la elaboración de gela na a base de suero ........20 Procedimiento para la elaboración de requesón ............................... 21 Procedimiento para la elaboración de queso panela .........................22 Procedimiento para la elaboración de queso Co ja ..........................23 Procedimiento para la elaboración de queso Chihuahua ................... 24 Procedimiento para la elaboración de queso ranchero...................... 26 Procedimiento para la elaboración de -

Sonora: Productos Y Preparaciones Tradicionales

SONORA: PRODUCTOS Y PREPARACIONES TRADICIONALES. (PALETA DE SABORES GRAFICA) CULINARY A R T SCHOOL . MAESTRÍA EN COCINAS DE MÉXICO. ACTIVIDAD 1 BLOQUE 1 UNIDAD 7 LIC. VÍCTOR JOSUÉ PALMA TENORIO. Cazuela o Caldillo. Cocido o Puchero. Gallina Pinta. Chivichangas.(Res, Frijol y Queso) Menudo. Chorizo con Carne de res con Hígado Papas. Chile. Caldo de Queso. Bistec Ranchero. encebollado. Quesadillas con Tortillas de y Ensalada de Pollo. Bistec trigo. Caldo de queso. Bistec Ranchero. Ranchero. Calabacitas con queso. Carne de res con chile. Ejotes con Chivichangas. Las Chivichangas. Zona Chile. Chorizo de puerco Norte Quesadillas con con papas. Caldo de pollo Zona del Zona con arroz. desierto del rio tortillas de Maiz. Caldo de queso. de Altar. Sonora. Chiles rellenos. Chorizo con papas. Guisado de machaca con Machaca Con Sonora. Sierra verdura. Tomate con carne. Albóndigas verdura. Sierra Sur. Cazuela. Pozole de maíz. Pozole de Trigo. Puchero. Norte. Cazuela. Hígado encebollado. Chivichangas. Costa Menudo. Bistec Ranchero. Zona Chicharrón de Quesadilla de trigo. Sur. Sur. res. Quelites. Carne de res con chile. Enchiladas. Habas Carne deshebrada guisada. Picadillo. Albóndigas con arroz. Frijoles. Frutas Gallina Pucheros Café Chiles rellenos. Atole. Pinta. Champurrado Machaca con Quesadillas de Mezcal. verdura. trigo. de chocolate. Tamales de elote. Picadillo. Tortillas de maíz y trigo. Chivichangas Cocinas de res. ESTADO DE SONORA. • En el estado de Sonora se encuentra una gran variedad de platillos dependiendo del estado que se encuentren aun que siempre hay una pequeña constante en todas las cocinas. Las amas de casa elaboran diariamente tortillas de harina de trigo, a mano, o pan de casa. -

Kahla Watkins F All 2018

FALL 2018 FALL KAHLA WATKINS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 目次 INTRODUCTION 4 THESIS STATEMENT 6 METHODOLOGY 8 Books and Articles 8 Interview 11 Observations 11 RESEARCH 12 Background Information 12 Target Market 15 Marketing and Promotion 16 Design Considerations 18 ACTIONS TAKEN 22 Brand Identity 22 Collateral 24 Advertising 28 Web Design 34 Social Media 34 Merchandise 35 CONCLUSION 36 APPENDIX 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 38 2 3 MISO HUNGRY THESIS INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION 前書き When I was young I went through the typical middle school anime phase that seems to be a common stage of life. And like most everyone else, I outgrew that interest. However, in recent years my two brothers got me to start watching it again. Because I am older now, my appreciation for the Japanese culture grew. I noticed there were specific Japanese cuisines repeated in each show. One of special dishes was Onigri, which is a rice ball. After seeing the preparation of the dish in several episodes, I thought I would try making it myself. With the help of my mom, we attempted the dish, and it was an epic fail. Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a Japanese food truck that offered genuine Japanese comfort foods such as Onigri? 4 5 MISO HUNGRY THESIS THESIS THESIS 論文 This project involved the marketing and branding of a Japanese food truck called Miso Hungry. This was accomplished through extensive research in the food truck industry, Japanese cuisine, the Japanese pop culture, artists such as Takashi Murakami, and new Japanese design as well as traditional Japanese design. -

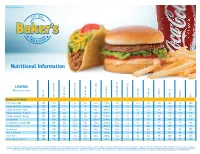

Nutritional Information

BakersDriveThru.com Nutritional Information LEGEND Vegetarian Item Cholesterol (mg) Cholesterol Sodium (mg) (g) Protein Vitamin A Calories from Fat Calories Fat (g) Total Fat (g) Saturated Fat (g) Trans (g) Carbohydrates Fiber (g) Dietary Sugars (g) Vitamin C Calcium Iron American Kitchen Boca® Burger 510 230 27g 9g 0g 45mg 1230mg 46g 7g 10g 25g 8% 10% 2% 20% Chicken Sandwich - Caribbean 450 200 23g 5g 0g 55mg 980mg 44g 2g 16g 17g 15% 15% 4% 10% Chicken Sandwich - Grilled 460 220 24g 5g 0g 60mg 1080mg 41g 3g 10g 21g 8% 15% 4% 15% Chicken Sandwich - Monterey 410 170 18g 8g 0g 65mg 1150mg 36g 2g 7g 26g 15% 35% 25% 15% Chicken Sandwich - Teriyaki 470 210 24g 5g 0g 55mg 1310mg 44g 3g 12g 20g 8% 15% 4% 15% Double Baker 760 430 49g 21g 1g 150mg 1390mg 37g 2g 10g 42g 8% 10% 6% 25% Grilled Cheese Sandwich 510 300 35g 15g 0g 55mg 1120mg 35g 2g 6g 18g 2% 4% 2% 10% Monterey Double 730 420 47g 20g 0.5g 140mg 1040mg 36g 2g 8g 40g 20% 30% 45% 25% Onion Burger 480 220 25g 12g 0.5g 95mg 770mg 34g 1g 6g 31g 0% 8% 4% 20% Plain Hamburger 270 90 10g 3.5g 0g 35mg 300mg 30g 1g 4g 15g 0% 4% 4% 15% Single Baker 400 190 21g 6g 0g 50mg 500mg 35g 2g 8g 15g 8% 10% 4% 15% Single Baker w/ Cheese 500 270 30g 12g 0g 75mg 920mg 36g 2g 9g 21g 8% 10% 4% 15% In the breakfast and meals sections, the low and high options reflect minimum and maximum caloric values for possible combinations. -

TACOS Build Your Own Tacos

LUNCH / DINNER DRINKS SEASONAL SPECIALS DESSERT BRUNCH ANTOJITOS TACOS Build Your Own Tacos. GUACAMOLE MIXTO FRITO 12. Prepared with Housemade Corn Tortillas Jalapeños, Onions, Cilantro, Calamari, Shrimp, Octopus, Tomatoes, and Fresh Lime Battered and Fried, served MUSICOS 14. SMALL 9. with Chiles & Chile Aioli Spicy Chopped Pork LARGE 16. CHILE CON QUESO 10. GRILLED TEXAS REDFISH 18. CRAB CAKE 18. Spicy Cheese and with Chipotle Slaw Jumbo Lump Crabmeat Served Fire-Roasted Pepper Dip with Chipotle Sauce GRILLED SALMON 16. MUSHROOM QUESADILLAS 8. Tamarind-Glazed with QUESO FLAMEADO 12. Fresh Corn Tortillas with Grilled Onions and Mango Cheese Casserole with Mushrooms, Poblano Peppers, Salsa Chorizo and Mexican Cheeses 19. ADD CHICKEN 2. DIABLO SHRIMP CEVICHE 18. Bacon-Wrapped with Jack Gulf Shrimp and Red Snapper NACHOS 9. Cheese with Jalapeños, Tomatoes, with Beans, Cheese, Sour and Avocado Cream, Jalapeños, Pico de TACOS DE PULPO CAZUELITA 18. Gallo, and Guacamole Wood Oven Roasted Octopus CEVICHE TOSTADA 12. Tacos with Coleslaw, Grilled Ceviche on a Crispy Corn ADD CHICKEN FAJITAS 5. Potatoes, and Chipotle Aioli Tostada with Queso Fresco, ADD BEEF FAJITAS 8. Onions, and Cilantro AL PASTOR 14. Wood Oven Roasted Pork and Pineapple MAMA NINFA’S ORIGINAL CALDOS Y ENSALADAS ADOBO RABBIT TACOS 24. TACOS AL CARBON Served with Garbanzo Purée, SOUP OF THE DAY MKT Fajitas in a Flour Tortilla with fresh Corn Tortillas, and Pico de Gallo, Guacamole, and Guajillo Sauce CALDO XOCHITL (SO-CHEEL) SOUP 9. Chile con Queso Shredded Chicken, Sliced Avocado, and Pico de Gallo ONE TACO A LA NINFA Beef Fajitas 14. NINFA’S MIXTAS Chicken Fajitas 12. -

Passport to the World (Mexico) Haleigh Wilcox About Mexico

Passport to the World (Mexico) Haleigh Wilcox About Mexico Official name : United Mexican States Established : September 16th ,1810 Type of Goverment : Federal, Republic, Constitution Republic and has a Presidential Representitive Current President of Mexico : Andres Manuel Lopez Obrabor Haleigh Wilcox Mexico’s Geography in the World Mexico’s Own Geography Continent it’s in : South America Capital City : Mexico City Latitude : 23.6345 Other Major Cities : Ecatepec, Puebla, Guadalajara, Juarez Other Geographic Features : Lake Chapala, Sonoran Desert, Sierra Side of Equator : North Madres, Chihuahuan Desert o o Average Tempurature : December-71 F/21.67 C Size : 758,449 sq. miles June-57oF/13.89oC Major Tourist Sites : Teotihuacan, Copper Canyon, Cozumel, Tulum, El Arco, San Ignacio Lagoon Haleigh Wilcox About The People Mexico’s Economy Population : 110,939,132 Basic Unit of Currency : Peso Major Languages Spoken : Nahuatl (22.89%), Mayan Major Agricultural Products : sorghum, chili peppers, barley*, (12.63), Mixteco (7.04%), Zapoteco (6.84%), Tzeltal (6.18%) avocados*, blue agave, coffee* Manufactured Products : Oil, Cotton, Silver, Cars, Insulated Wires Area Percentage Where People Live : 33% Rural, 77% and Cables, Tractors Urban Type of region : Developing Haleigh Wilcox Mexico’s Culture House Type : Mexican houses, Mexican Ranch Homes, Some famous People : Salma Hayek (2002 Film Actress and Spanish villa, Adobe, Misision Style Mansion Producer) and Espinoza Paz (2006 Latin Musician) Clothing Type : Slacks or jeans with a button-down shirt or Foods We Eat That Are Prepared In Mexico : Tacos, T-shirt for men and a skirt or slacks with a blouse or T-shirt Burritos, Tostadas for women. -

Toronto's Food Truck Scene Is a Must-Eat Destination

FOOD TRUCKS Dig In Toronto’s food truck scene is a must-eat destination By Heather Hudson hen you’re enjoying the vibe of a city, the last thing you want to do is desert the vibrant streetscape to Wrefuel. In Toronto, you don’t have to. Te food truck scene in the city has exploded in recent years, ofering a mouthwatering selection of cuisines from tradition- al fare, like hot dogs and burgers, to the exceptionally creative (fawafe, anyone?). As you cruise around the city or hit the summer’s festi- vals, chances are, you’ll stumble upon a foodie experience just waiting to happen. Better yet, grab a map and consult toronto- foodtrucks.ca (@foodtrucksTO on Twitter) to fnd out where your next gastronomical adventure will be. It’s a great way to explore the city and experience some amazing food that you won’t fnd at a sit-down diner. Need some ideas to get started? Here’s just a small selection of crowd favourites. Hunt them down and get eating! ALIJANDRO’S KITCHEN Billing their food experience as “culinary culture shock,” own- ers Samer Khatib and Tarek Jaber blend Mexican and Mediterranean dishes, including tacos, salads and desserts. Teir signature ofering is the “fawafe,” a wafe cone made from falafel batter. It’s the texture of a sweet wafe cone but with that savoury falafel favour. Try it with standard fllings or dig into the Right: A new taste more substantial avocado chicken fawafe. Bonus for diners sensation: the fawaffle, with dietary restrictions: Te fawafe is naturally gluten-free, Nitr/Shutterstock.com from Alijandro’s Kitchen high in protein and low in carbs. -

A Mexican Food Fiesta in North Park!

Sunday, December 16, 2018 City Tacos - A Mexican food fiesta in North Park! Do you know that old Rachael Ray show where she was challenged to eat three delicious meals in one day without spending more than $40? Well, I found a place that could have easily been on her list! A friend and I had the opportunity to dine at City Tacos in North Park. Let me tell you it was a taco fiesta! The menu offers a great selection for meat eaters, vegetarians, and seafood lovers as well! Let's begin with the salsa bar. In addition to the regular green and red salsas that most tacos shops offer, I appreciated the chunks of jicama and cucumber available to cool your palate after eating some heat. In addition they had some signature salsas that were new to me! We sampled the whole rainbow and I especially liked the salsa mango habanero on some chips with guacamole....muy delicioso! And I REALLY REALLY liked the cilantro salsa! If they sold that in a bottle I would buy it! The chips were fresh from the fryer and the guacamole was the real thing! No thinned down saucy guac here! My friend and I grew up in South San Diego, with some taco shops within walking distance that we frequented on a regular basis even before we could drive, so we've been eating tacos forever! We always have Carne Asada and Pollo Asada tacos, so we opted to try a birria taco here at City Tacos. First of all the meat portion was very generous as you can see, topped with pickled onions. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Tax Increment Finance Best Practices Reference Guide

Tax Increment Finance Best Practices Reference Guide cdfa Council of Development Finance Agencies TAX INCREMENT FINANCE BEST PRACTICES REFERENCE GUIDE cdfa Council of Development Finance Agencies COPYRIGHT © 2007 by the Council of Development Finance Agencies and the International Council of Shopping Centers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication my be produced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is available with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional services. If legal advise or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. –From a Declaration of Principles jointly adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers. Photographs for case studies were submitted by case study authors. Tax Increment Finance Best Practices Reference Guide Council of Development Finance Agencies and International Council of Shopping Centers EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Council of Development Finance Agencies (CDFA) and the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC) have collaborated with teams of Tax Increment Finance (TIF) experts from across the country to develop this reference guide. The Reference Guide addresses what TIF is, why it should be used and how best to apply the TIF tool. The Reference Guide also highlights TIF projects from across the country and discusses how they can be applied to address many common economic development issues.