Clothing the Postcolonial Body: Art, Artifacts and Action in South Eastern Australia1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Art Studies November 2018 Landscape Now British Art Studies Issue 10, Published 29 November 2018 Landscape Now

British Art Studies November 2018 Landscape Now British Art Studies Issue 10, published 29 November 2018 Landscape Now Cover image: David Alesworth, Unter den Linden, 2010, horticultural intervention, public art project, terminalia arjuna seeds (sterilized) yellow paint.. Digital image courtesy of David Alesworth. PDF generated on 30 July 2019 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Fire-Stick Picturesque: Landscape Art and Early Colonial Tasmania, Julia Lum Fire-Stick Picturesque: Landscape Art and Early Colonial Tasmania Julia Lum Abstract Drawing from scholarship in fire ecology and ethnohistory, thispaper suggests new approaches to art historical analysis of colonial landscape art. British artists in the colony of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) relied not only on picturesque landscape conventions to codify their new environments, but were also influenced by local vegetation patterns and Indigenous landscape management practices. -

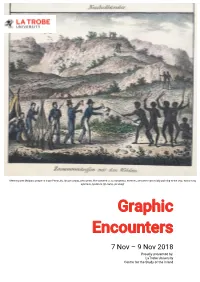

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

Your Candidates Metropolitan

YOUR CANDIDATES METROPOLITAN First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria Election 2019 “TREATY TO ME IS A RECOGNITION THAT WE ARE THE FIRST INHABITANTS OF THIS COUNTRY AND THAT OUR VOICE BE HEARD AND RESPECTED” Uncle Archie Roach VOTING IS OPEN FROM 16 SEPTEMBER – 20 OCTOBER 2019 Treaties are our self-determining right. They can give us justice for the past and hope for the future. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be our voice as we work towards Treaties. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be set up this year, with its first meeting set to be held in December. The Assembly will be a powerful, independent and culturally strong organisation made up of 32 Victorian Traditional Owners. If you’re a Victorian Traditional Owner or an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person living in Victoria, you’re eligible to vote for your Assembly representatives through a historic election process. Your voice matters, your vote is crucial. HAVE YOU ENROLLED TO VOTE? To be able to vote, you’ll need to make sure you’re enrolled. This will only take you a few minutes. You can do this at the same time as voting, or before you vote. The Assembly election is completely Aboriginal owned and independent from any Government election (this includes the Victorian Electoral Commission and the Australian Electoral Commission). This means, even if you vote every year in other elections, you’ll still need to sign up to vote for your Assembly representatives. Don’t worry, your details will never be shared with Government, or any electoral commissions and you won’t get fined if you decide not to vote. -

William Barak

WILLIAM BARAK A brief essay about William Barak drawn from the booklet William Barak - Bridge Builder of the Kulin by Gibb Wettenhall, and published by Aboriginal Affairs Victoria. Barak was educated at the Yarra Mission School in Narrm (Melbourne), and was a tracker in the Native Police before, as his father had done, becoming ngurungaeta (clan leader). Known as energetic, charismatic and mild mannered, he spent much of his life at Coranderrk Reserve, a self-sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville. Barak campaigned to protect Coranderrk, worked to improve cross-cultural understanding and created many unique artworks and artefacts, leaving a rich cultural legacy for future generations. Leader William Barak was born into the Wurundjeri clan of the Woi wurung people in 1823, in the area now known as Croydon, in Melbourne. Originally named Beruk Barak, he adopted the name William after joining the Native Police as a 19 year old. Leadership was in Barak's blood: his father Bebejan was a ngurunggaeta (clan head) and his Uncle Billibellary, a signatory to John Batman's 1835 "treaty", became the Narrm (Melbourne) region's most senior elder. As a boy, Barak witnessed the signing of this document, which was to have grave and profound consequences for his people. Soon after white settlement a farming boom forced the Kulin peoples from their land, and many died of starvation and disease. During those hard years, Barak emerged as a politically savvy leader, skilled mediator and spokesman for his people. In partnership with his cousin Simon Wonga, a ngurunggaeta, Barak worked to establish and protect Coranderrk, a self- sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville, and became a prominent figure in the struggle for Aboriginal rights and justice. -

Final Hannah Online Credits

Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits WRITTEN & PRESENTED BY HANNAH GADSBY ------ DIRECTED & CO-WRITTEN BY MATTHEW BATE ------------ PRODUCED BY REBECCA SUMMERTON ------ EDITOR DAVID SCARBOROUGH COMPOSER & MUSIC EDITOR BENJAMIN SPEED ------ ART HISTORY CONSULTANT LISA SLADE ------ 1 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits ARTISTS LIAM BENSON DANIEL BOYD JULIE GOUGH ROSEMARY LAING SUE KNEEBONE BEN QUILTY LESLIE RICE JOAN ROSS JASON WING HEIDI YARDLEY RAYMOND ZADA INTERVIEWEES PROFESSOR CATHERINE SPECK LINDSAY MCDOUGALL ------ PRODUCTION MANAGER MATT VESELY PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS FELICE BURNS CORINNA MCLAINE CATE ELLIOTT RESEARCHERS CHERYL CRILLY ANGELA DAWES RESEARCHER ABC CLARE CREMIN COPYRIGHT MANAGEMENT DEBRA LIANG MATT VESELY CATE ELLIOTT ------ DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY NIMA NABILI RAD SHOOTING DIRECTOR DIMI POULIOTIS SOUND RECORDISTS DAREN CLARKE LEIGH KENYON TOBI ARMBRUSTER JOEL VALERIE DAVID SPRINGAN-O’ROURKE TEST SHOOT SOUND RECORDIST LACHLAN COLES GAFFER ROBERTTO KARAS GRIP HUGH FREYTAG ------ 2 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits TITLES, MOTION GRAPHICS & COLOURIST RAYNOR PETTGE DIALOGUE EDITOR/RE-RECORDING MIXER PETE BEST SOUND EDITORS EMMA BORTIGNON SCOTT ILLINGWORTH PUBLICITY STILLS JONATHAN VAN DER KNAPP ------ TOKEN ARTISTS MANAGING DIRECTOR KEVIN WHTYE ARTIST MANAGER ERIN ZAMAGNI TOKEN ARTISTS LEGAL & BUSINESS CAM ROGERS AFFAIRS MANAGER ------ ARTWORK SUPPLIED BY: Ann Mills Art Gallery New South Wales Art Gallery of Ballarat Art Gallery of New South Wales Art Gallery of South Australia Australian War Memorial, Canberra -

Rachel Perkins

Keynote address / Rachel Perkins I thought I would talk today about a project called First Australians, which is a documentary project. We are still in the midst of it. When I talk to people about it, like taxi drivers, they ask “What do you do?” and I say I make films. They say, “What are you working on?” and I say, “I’m working on this documentary series called First Australians” and they go “Oh great, it is about the migrant community coming to Australia” and I say, “No, no! It is actually about the first Australians, Indigenous Australians. So, we are still grappling with the title and whether it is going to be too confusing for people to grasp. But the name First Australians sort of makes the point of it trying to claim the space as Australia’s first people. If anyone has any better suggestions, come up to me at the end of the session! First Australians. It is probably the most challenging project that I’ve worked on to date. It is the largest documentary series to be undertaken in Australia. It is being made by a group of Indigenous Australians under the umbrella of Blackfella Films, which is our company. It has a national perspective and it is really the history of colonisation, which is a big part of our story. It charts the period from the 1780s through to 1993. It began in 2002 when Nigel Milan, who was the then General Manager of SBS, approached me. They had shown a series on SBS called 500 Nations, which is a series on Native American people. -

ACUADS 08/09 Research

SITES OF ACTIVITY ACUADS 08/09 RESEARCH Australian Council of University Art and Design Schools ON THE EDGE CONTENTS 2 Dr John Barbour INTRODUCTION Nanoessence Life and Death at a Nano Level 4 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY The Silk Road Project Dance and Embodiment in the Age of Motion Capture 6 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY Envisaging Globalism Victoria Harbour Young Artists Initiative 8 Globalisation and Chinese Traditional Art and Art Education 22 VCA Sculpture & Spatial Practice in Contempora2 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY, SUN YaT SEN UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Steam The Papunaya Partnership A New Paradigm for the Researching and 10 Transforming the Mundane 24 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY Teaching of Indigenous Art UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Creative Exchange in the Tropical Environment 12 JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY 26 The Creative Application of Knowledge UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA ARTEMIS (Art Educational Multiplayer Interactive Space) Second Skins 14 28 MONASH UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA An Audience with Myself How Does “Edgy” Research 186 Mapping – Unmapping Memory 30 Foster Interesting Innovative Teaching? NATIONAL ART SCHOOL, SYDNEY UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY Activating Studio Art 20 Arrivals and Departures Collaborative Practice in the Public Domain 32 RMIT UNIVERSITY THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 34 ACUADS MEMBERS 2 INTRODUCTION From the sculptural transformation of scrap metal to the use of nanotechnology in a multi-media installation that interrogates humanism; from online learning about the art of the ancient Greeks to a partnership between a big city art school and a group of indigenous printmakers living in a remote community, this report demonstrates the diversity of research being undertaken within Australian university art and design schools. -

William Barak Australia’S Leading Civil Rights Figure of the 19Th Century

William Barak Australia’s leading civil rights figure of the 19th Century William Barak was born at Brushy Creek in present day Wonga Park in 1823. It was named after his cousin Simon Wonga who preceded Barak as Ngurungaeta (Headman, pronounced ung-uh-rung-eye-tuh) of the Wurundjeri. Both Wonga and Barak had been present as 13 and 11 year olds in 1835 when John Batman met tribal Elders on the Plenty River. Batman claimed he was purchasing their land, but to the Wurundjeri it was a Tanderum Ceremony, inviting white people to share the bounty and stewardship of the land. Apart from having been decimated by the smallpox holocausts of 1789 and 1828, the motivation for offering to share the land was that the escaped convict William Buckley had warned them for many years that white men would come with terrible weapons and take the land. The Wurundjeri were soon to be massively disappointed when the incoming stream of white people showed a complete ignorance on any principles of ecological management, and brought even more diseases. Within a decade the Wurundjeri were driven from their lands and prevented from conducting annual burning off to regenerate food sources and prevent bushfires. The remnants of the Wurundjeri were forced to either live in poverty on the urban fringes, or in camps along the Yarra such as at Bolin-Bolin Billabong and Pound Bend in Warrandyte. Both Barak and Wonga meanwhile set about gaining an education in the ways of the white man with Barak attending the government’s Yarra Mission School from 1837 to 1839, then joining the Native Mounted Police in 1844. -

Tasmanian Aboriginality at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

Article Type: Original Article Corresponding author mail-id: [email protected] “THIS EXHIBITION IS ABOUT NOW”: Tasmanian Aboriginality at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Christopher Berk UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ABSTRACT This article focuses on the design and execution of two exhibits about Tasmanian Aboriginality at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. The first is a Tasmanian Aboriginal group exhibit from 1931, which was heavily informed by ideologies of Tasmanian primitivity and extinction. The second is the 2008 tayenebe, a celebration of the resurgence of fiber work among Tasmanian Aboriginal women. In each instance, the Tasmanian Aboriginal people are on display, but the level of community control and subtext is notably different. This article builds on discussions of cultural revitalization and reclamation by showing the process and how it is depicted for public consumption. [cultural revitalization, representation, indigeneity, Tasmania, Australia] Australia’s Aboriginal peoples have been central to how anthropologists have historically thought about progress and difference. Tasmania’s Aboriginal peoples receive less attention, both in Australia and in discussions of global indigenous movements. Before and after their supposed extinction in 1876, they were considered the most “primitive” culture ever documented (Darwin 2004; Stocking 1987; Tylor 1894; among many others). Ideologies of primitivism have historically been perpetuated and disseminated by cultural institutions around the world. James Clifford (1997) recounts a 1989 community consultation meeting with Tlingit representatives at the Portland Museum of Art during which the Tlingit Author Manuscript people told politically motivated tales about community concerns like land rights. The story of This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. -

Making an Expedition of Herself: Lady Jane Franklin As Queen of the Tasmanian Extinction Narrative

Making an Expedition of Herself: Lady Jane Franklin as Queen of the Tasmanian Extinction Narrative AMANDA JOHNSON University of Melbourne Figure 1. Julie Gough, Ebb Tide (1998). © Ricky Maynard/Licensed by Viscopy, 2015. Image courtesy the artist and STILLS Gallery JASAL: Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature 14.5 In her site-specific installation Ebb Tide (The Whispering Sands) (Figure 1) from 1998, the artist Julie Gough constructs sixteen pyrographically inscribed life-size, two-dimensional figures of British colonialists who collected Tasmanian Aboriginal people and cultural materials for ethnographic purposes. Gough’s matriarchal Aboriginal family comes from far north-east Tasmania, Tebrikunna, where her ancestor Woretemoeteyenner, one of the four daughters of the warrior Mannalargenna, was born around 1797. Installed across a tidal flat at Eaglehawk Neck in southern Tasmania, one image shows the smiling, half-submerged colonial Governor’s wife Jane Franklin, who is neither arriving nor departing, waving nor drowning.1 The figure derives from a youthful portrait of Franklin by Amélie Romilly that was globally disseminated by Franklin herself across her lifetime (reproduced in Alexander, insert 198a). One cannot be sure whether the figure, as with any fragment or talisman of history, will be submerged, exposed or worn away. The white colonial authority figure loses its historical power as the water rises and settles, bleaching the pigment down. So Gough critiques the tragically dislocating ethnographic obsessions of early settler colonists, who are disabled and flattened, reduced to two-dimensional incursions in a space which, heretofore, they have forcibly, dimensionally occupied. Tasmania has recently produced and/or inspired a stockpile of literary postcolonial novels, including realist, burlesque, and mythopoetic treatments of cannibalism, violent miscegenation, genocide and natural species extinction narratives. -

FIRST CONTACT in PORT PHILLIP Within This Section, Events Are Discussed Relating to the Colonisation of Port Phillip in 1835

READINGS IN AUSTRALIAN HISTORY -The History you were never taught THEME 6: FIRST CONTACT IN PORT PHILLIP Within this section, events are discussed relating to the colonisation of Port Phillip in 1835. The names of the principal characters involved, that of William Buckley, John Batman, John Pascoe Fawkner and William Barak are well known to the public. However as the saying goes, history is written by the winners. This section therefore endeavours to lift the veil on this period of our colonial history through an understanding of the Aboriginal perspective. A little understood narrative dictated by William Barak in 1888 is examined to reveal new insights about the influence of William Buckley on Aboriginal thinking, and the location of the 1835 treaty meeting with Batman. AH 6.1 Buckley’s Adjustment to Tribal Life AH 6.2 Murrungurk’s Law AH 6.3 Barak’s meeting with Batman AH 6.4 Interpreting Barak’s story AH 6.5 Batman’s second bogus treaty AH 6.6 The Naming of the Yarra River in 1835 AH 6.7 Melbourne’s feuding founding fathers THEME 6 QUESTIONS FOR CONSIDERATION 1. If Buckley survived 32 years in Aboriginal society, was he as dumb as he was painted by some colonists? 2. If Batman had his treaties signed by eight Aboriginals, in ink, on a log, in middle of winter, how come there is not one ink blot, smudge, fingerprint or raindrop? 3. Who was the nicer person, John Batman or John Pascoe Fawkner? BUCKLEY’S ADJUSTMENT TO TRIBAL LIFE William Buckley is of course firmly entrenched in Australian history and folklore as ‘The Wild White Man’. -

Julie Gough: Hunting Ground Julie Gough’S Forensic Archaeology of National Forgetting

JULIE GOUGH: HUNTING GROUND JULIE GOUGH’S FORENSIC ARCHAEOLOGY OF NATIONAL FORGETTING By Joseph Pugliese In the course of his essay, “What is a Nation,” the nineteenth-century French historian Ernest Renan catalogues the acts of violence that are constitutive of the processes of nation building. He then pauses to reflect on the role of forgetting: Forgetting, I would even say historical error, is an essential factor in the creation of a nation and it is for this reason that progress of historical studies often poses a threat to nationality. Historical inquiry, in effect, throws light on the violent acts that have taken place at the origin of every political formation, even those that have been most benevolent in their consequences. Unity is always brutally achieved. 1 Renan’s insight into the constitutive roles that violence and forgetting play in the foundation of a nation powerfully resounds in the context of the Australian colonial state. From the moment that the Australian continent was invaded and colonized by the British in 1788, it witnessed both random and systematic campaigns of attempted Indigenous genocide. The collective acts of resistance deployed by Australia’s Indigenous people in order to defend their unceded lands and to safeguard their very lives provoked settler campaigns of massacre in order to secure possession of the continent and its islands. This genocidal violence sits at the very heart of the history of the Australian nation-state. Yet, when cast in the context of Renan’s astute observations, the violence of this history is precisely what had to be forgotten by non-Indigenous Australians in order to preserve the myth of the Australian nation as a state that has never experienced war on its own terrain.