Working with Aboriginal Protocols in a Documentary Film About Colonisation and Growing up White in Tasmania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Art Studies November 2018 Landscape Now British Art Studies Issue 10, Published 29 November 2018 Landscape Now

British Art Studies November 2018 Landscape Now British Art Studies Issue 10, published 29 November 2018 Landscape Now Cover image: David Alesworth, Unter den Linden, 2010, horticultural intervention, public art project, terminalia arjuna seeds (sterilized) yellow paint.. Digital image courtesy of David Alesworth. PDF generated on 30 July 2019 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Fire-Stick Picturesque: Landscape Art and Early Colonial Tasmania, Julia Lum Fire-Stick Picturesque: Landscape Art and Early Colonial Tasmania Julia Lum Abstract Drawing from scholarship in fire ecology and ethnohistory, thispaper suggests new approaches to art historical analysis of colonial landscape art. British artists in the colony of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) relied not only on picturesque landscape conventions to codify their new environments, but were also influenced by local vegetation patterns and Indigenous landscape management practices. -

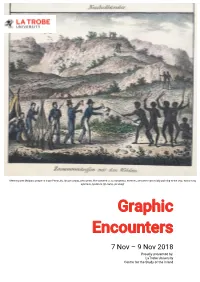

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

National Reconciliation Week Let’S Walk the Talk! 27 May – 3 June Let’S Walk the Talk!

National Reconciliation Week National Reconciliation Week Let’s walk the talk! 27 May – 3 June Let’s walk the talk! Aboriginal Sydney: A guide to important places of the past and present, 2nd Edition Melinda HINKSON and Alana HARRIS Sydney has a rich and complex Aboriginal heritage. Hidden within its burgeoning city landscape lie layers of a vibrant culture and a turbulent history. But, you need to know where to look. Aboriginal Sydney supplies the information. Aboriginal Sydney is both a guide book and an alternative social history told through an array of places of significance to the city’s Indigenous people. The sites, and their accompanying stories and photographs, evoke Sydney’s ancient past and celebrate the living Aboriginal culture of today. Back on The Block: Bill Simon’s Story Bill SIMON, Des MONTGOMERIE and Jo TUSCANO Stolen, beaten, deprived of his liberty and used as child labour, Bill Simon’s was not a normal childhood. He was told his mother didn’t want him, that he was ‘the scum of the earth’ and was locked up in the notorious Kinchela Boys Home for eight years. His experiences there would shape his life forever. Bill Simon got angry, something which poisoned his life for the next two decades. A life of self abuse and crime finally saw him imprisoned. But Bill Simon has turned his life around and in Back on the Block, he hopes to help others to do the same. These days Bill works on the other side of the bars, helping other members of the Stolen Generations find a voice and their place; finally putting their pain to rest. -

Tatz MIC Castan Essay Dec 2011

Indigenous Human Rights and History: occasional papers Series Editors: Lynette Russell, Melissa Castan The editors welcome written submissions writing on issues of Indigenous human rights and history. Please send enquiries including an abstract to arts- [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-9872391-0-5 Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Indigenous Human Rights and History Vol 1(1). The essays in this series are fully refereed. Editorial committee: John Bradley, Melissa Castan, Stephen Gray, Zane Ma Rhea and Lynette Russell. Genocide in Australia: By Accident or Design? Colin Tatz © Colin Tatz 1 CONTENTS Editor’s Acknowledgements …… 3 Editor’s introduction …… 4 The Context …… 11 Australia and the Genocide Convention …… 12 Perceptions of the Victims …… 18 Killing Members of the Group …… 22 Protection by Segregation …… 29 Forcible Child Removals — the Stolen Generations …… 36 The Politics of Amnesia — Denialism …… 44 The Politics of Apology — Admissions, Regrets and Law Suits …… 53 Eyewitness Accounts — the Killings …… 58 Eyewitness Accounts — the Child Removals …… 68 Moving On, Moving From …… 76 References …… 84 Appendix — Some Known Massacre Sites and Dates …… 100 2 Acknowledgements The Editors would like to thank Dr Stephen Gray, Associate Professor John Bradley and Dr Zane Ma Rhea for their feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Myles Russell-Cook created the design layout and desk-top publishing. Financial assistance was generously provided by the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law and the School of Journalism, Australian and Indigenous Studies. 3 Editor’s introduction This essay is the first in a new series of scholarly discussion papers published jointly by the Monash Indigenous Centre and the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law. -

Māori and Aboriginal Women in the Public Eye

MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 KAREN FOX THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fox, Karen. Title: Māori and Aboriginal women in the public eye : representing difference, 1950-2000 / Karen Fox. ISBN: 9781921862618 (pbk.) 9781921862625 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Women, Māori--New Zealand--History. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--History. Women, Māori--New Zealand--Social conditions. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--Social conditions. Indigenous women--New Zealand--Public opinion. Indigenous women--Australia--Public opinion. Women in popular culture--New Zealand. Women in popular culture--Australia. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--New Zealand. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.4880099442 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: ‘Maori guide Rangi at Whakarewarewa, New Zealand, 1935’, PIC/8725/635 LOC Album 1056/D. National Library of Australia, Canberra. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix Illustrations . xi Glossary of Māori Words . xiii Note on Usage . xv Introduction . 1 Chapter One . -

Australian Elegy: Landscape and Identity

Australian Elegy: Landscape and Identity by Janine Gibson BA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of (Doctor of Philosophy) Deakin University December, 2016 Acknowledgments I am indebted to the School of Communication and Creative Arts at Deakin University (Geelong), especially to my principal supervisor Professor David McCooey whose enthusiasm, constructive criticism and encouragement has given me immeasurable support. I would like to gratefully acknowledge my associate supervisors Dr. Maria Takolander and Dr. Ann Vickery for their interest and invaluable input in the early stages of my thesis. The unfailing help of the Library staff in searching out texts, however obscure, as well as the support from Matt Freeman and his helpful staff in the IT Resources Department is very much appreciated. Sincere thanks to the Senior HDR Advisor Robyn Ficnerski for always being there when I needed support and reassurance; and to Ruth Leigh, Kate Hall, Jo Langdon, Janine Little, Murray Noonan and Liam Monagle for their help, kindness and for being so interested in my project. This thesis is possible due to my family, to my sons Luke and Ben for knowing that I could do this, and telling me often, and for Jane and Aleisha for caring so much. Finally, to my partner Jeff, the ‘thesis watcher’, who gave me support every day in more ways than I can count. Abstract With a long, illustrious history from the early Greek pastoral poetry of Theocritus, the elegy remains a prestigious, flexible Western poetic genre: a key space for negotiating individual, communal and national anxieties through memorialization of the dead. -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Mckee, Alan (1996) Making Race Mean : the Limits of Interpretation in the Case of Australian Aboriginality in Films and Television Programs

McKee, Alan (1996) Making race mean : the limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4783/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Making Race Mean The limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs by Alan McKee (M.A.Hons.) Dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Glasgow in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow March 1996 Page 2 Abstract Academic work on Aboriginality in popular media has, understandably, been largely written in defensive registers. Aware of horrendous histories of Aboriginal murder, dispossession and pitying understanding at the hands of settlers, writers are worried about the effects of raced representation; and are always concerned to identify those texts which might be labelled racist. In order to make such a search meaningful, though, it is necessary to take as axiomatic certain propositions about the functioning of films: that they 'mean' in particular and stable ways, for example; and that sophisticated reading strategies can fully account for the possible ways a film interacts with audiences. -

Final Hannah Online Credits

Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits WRITTEN & PRESENTED BY HANNAH GADSBY ------ DIRECTED & CO-WRITTEN BY MATTHEW BATE ------------ PRODUCED BY REBECCA SUMMERTON ------ EDITOR DAVID SCARBOROUGH COMPOSER & MUSIC EDITOR BENJAMIN SPEED ------ ART HISTORY CONSULTANT LISA SLADE ------ 1 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits ARTISTS LIAM BENSON DANIEL BOYD JULIE GOUGH ROSEMARY LAING SUE KNEEBONE BEN QUILTY LESLIE RICE JOAN ROSS JASON WING HEIDI YARDLEY RAYMOND ZADA INTERVIEWEES PROFESSOR CATHERINE SPECK LINDSAY MCDOUGALL ------ PRODUCTION MANAGER MATT VESELY PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS FELICE BURNS CORINNA MCLAINE CATE ELLIOTT RESEARCHERS CHERYL CRILLY ANGELA DAWES RESEARCHER ABC CLARE CREMIN COPYRIGHT MANAGEMENT DEBRA LIANG MATT VESELY CATE ELLIOTT ------ DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY NIMA NABILI RAD SHOOTING DIRECTOR DIMI POULIOTIS SOUND RECORDISTS DAREN CLARKE LEIGH KENYON TOBI ARMBRUSTER JOEL VALERIE DAVID SPRINGAN-O’ROURKE TEST SHOOT SOUND RECORDIST LACHLAN COLES GAFFER ROBERTTO KARAS GRIP HUGH FREYTAG ------ 2 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits TITLES, MOTION GRAPHICS & COLOURIST RAYNOR PETTGE DIALOGUE EDITOR/RE-RECORDING MIXER PETE BEST SOUND EDITORS EMMA BORTIGNON SCOTT ILLINGWORTH PUBLICITY STILLS JONATHAN VAN DER KNAPP ------ TOKEN ARTISTS MANAGING DIRECTOR KEVIN WHTYE ARTIST MANAGER ERIN ZAMAGNI TOKEN ARTISTS LEGAL & BUSINESS CAM ROGERS AFFAIRS MANAGER ------ ARTWORK SUPPLIED BY: Ann Mills Art Gallery New South Wales Art Gallery of Ballarat Art Gallery of New South Wales Art Gallery of South Australia Australian War Memorial, Canberra -

Borderlines Film Festival 2013

Friday 1 to Sunday 17 March BORDERLINES FILM FESTIVAL 2013 borderlinesfilmfestival.org @borderlines #borderlines2013 2 / 3 A – Z Film Index Central Box Office 01432 340555 / #borderlines2013 / www.borderlinesfilmfestival.org film ProGrammer david sin PuTs a dozen films in The sPoTliGhT BeasTs of The souThern Wild (12a) p.15 Blackmail (PG) p.16 The conformisT (15) p.19 hiTchcock (12a) p.21 Showy, bold and richly imaginative, this debut Hitchcock’s final silent film with haunting Simply one of the most influential films Anthony Hopkins and Helen Mirren feature, set in a semi-mythical Deep South, London locations and live accompaniment of the 20th century and one of Festival in a wonderful behind-the-scenes drama is hard to resist from the accomplished Stephen Horne Patron Chris Menges’ favourites about the making of Psycho in The house (15) p.24 i Wish (PG) p.25 a laTe QuarTeT (15) p.27 mccullin (15) p.31 Kristin Scott Thomas in sparkling comedic From the director of Still Walking, a marvellous A nuanced affirmation of the power of music If you grew up in the ‘60s or ‘70s this form features in this sly, teasing conundrum evocation of childhood against the growing as inner and outer tensions threaten the honest and riveting documentary will stir of a movie with a strong backbite cloud of volcanic ash dynamics of a New York chamber quartet up strong memories no (15) p.34 rusT & Bone (15) p.39 sTarBuck (15) p.46 Wadjda (12a) p.50 Chilean director Larraín and lead Gael García Muscular and tender, this unlikely love story Warm, witty comedy -

ACUADS 08/09 Research

SITES OF ACTIVITY ACUADS 08/09 RESEARCH Australian Council of University Art and Design Schools ON THE EDGE CONTENTS 2 Dr John Barbour INTRODUCTION Nanoessence Life and Death at a Nano Level 4 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY The Silk Road Project Dance and Embodiment in the Age of Motion Capture 6 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY Envisaging Globalism Victoria Harbour Young Artists Initiative 8 Globalisation and Chinese Traditional Art and Art Education 22 VCA Sculpture & Spatial Practice in Contempora2 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY, SUN YaT SEN UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Steam The Papunaya Partnership A New Paradigm for the Researching and 10 Transforming the Mundane 24 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY Teaching of Indigenous Art UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Creative Exchange in the Tropical Environment 12 JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY 26 The Creative Application of Knowledge UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA ARTEMIS (Art Educational Multiplayer Interactive Space) Second Skins 14 28 MONASH UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA An Audience with Myself How Does “Edgy” Research 186 Mapping – Unmapping Memory 30 Foster Interesting Innovative Teaching? NATIONAL ART SCHOOL, SYDNEY UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY Activating Studio Art 20 Arrivals and Departures Collaborative Practice in the Public Domain 32 RMIT UNIVERSITY THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 34 ACUADS MEMBERS 2 INTRODUCTION From the sculptural transformation of scrap metal to the use of nanotechnology in a multi-media installation that interrogates humanism; from online learning about the art of the ancient Greeks to a partnership between a big city art school and a group of indigenous printmakers living in a remote community, this report demonstrates the diversity of research being undertaken within Australian university art and design schools. -

The Roving Party &

The Roving Party & Extinction Discourse in the Literature of Tasmania. Submitted by Rohan David Wilson, BA hons, Grad Dip Ed & Pub. School of Culture and Communication, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. October 2009. Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Writing). Abstract The nineteenth-century discourse of extinction – a consensus of thought primarily based upon the assumption that „savage‟ races would be displaced by the arrival of European civilisation – provided the intellectual foundation for policies which resulted in Aboriginal dispossession, internment, and death in Tasmania. For a long time, the Aboriginal Tasmanians were thought to have been annihilated, however this claim is now understood to be a fallacy. Aboriginality is no longer defined as a racial category but rather as an identity that has its basis in community. Nevertheless, extinction discourse continues to shape the features of modern literature about Tasmania. The first chapter of this dissertation will examine how extinction was conceived of in the nineteenth-century and traces the influence of that discourse on contemporary fiction about contact history. The novels examined include Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World by Mudrooroo, The Savage Crows by Robert Drewe, Manganinnie by Beth Roberts, and Wanting by Richard Flanagan. The extinctionist elements in these novels include a tendency to euglogise about the „lost race‟ and a reliance on the trope of the last man or woman. The second chapter of the dissertation will examine novels that attempt to construct a representation of Aboriginality without reference to extinction.