Arxiv:1904.07129V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 15 Apr 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking Dust Emission to Fundamental Properties in Galaxies: the Low-Metallicity Picture?

A&A 582, A121 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526067 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics Linking dust emission to fundamental properties in galaxies: the low-metallicity picture? A. Rémy-Ruyer1;2, S. C. Madden2, F. Galliano2, V. Lebouteiller2, M. Baes3, G. J. Bendo4, A. Boselli5, L. Ciesla6, D. Cormier7, A. Cooray8, L. Cortese9, I. De Looze3;10, V. Doublier-Pritchard11, M. Galametz12, A. P. Jones1, O. Ł. Karczewski13, N. Lu14, and L. Spinoglio15 1 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, UMR 8617, 91405 Orsay, France e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Laboratoire AIM, CEA/IRFU/Service d’Astrophysique, Université Paris Diderot, Bât. 709, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 3 Sterrenkundig Observatorium, Universiteit Gent, Krijgslaan 281 S9, 9000 Gent, Belgium 4 UK ALMA Regional Centre Node, Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK 5 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille – LAM, Université d’Aix-Marseille & CNRS, UMR 7326, 38 rue F. Joliot-Curie, 13388 Marseille Cedex 13, France 6 Department of Physics, University of Crete, 71003 Heraklion, Greece 7 Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Str. 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 8 Center for Cosmology, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA 9 Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Mail H30, PO Box 218, Hawthorn VIC 3122, Australia 10 Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 11 Max-Planck für Extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstr. 1, 85748 Garching-bei-München, Germany 12 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. -

THE 1000 BRIGHTEST HIPASS GALAXIES: H I PROPERTIES B

The Astronomical Journal, 128:16–46, 2004 July A # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE 1000 BRIGHTEST HIPASS GALAXIES: H i PROPERTIES B. S. Koribalski,1 L. Staveley-Smith,1 V. A. Kilborn,1, 2 S. D. Ryder,3 R. C. Kraan-Korteweg,4 E. V. Ryan-Weber,1, 5 R. D. Ekers,1 H. Jerjen,6 P. A. Henning,7 M. E. Putman,8 M. A. Zwaan,5, 9 W. J. G. de Blok,1,10 M. R. Calabretta,1 M. J. Disney,10 R. F. Minchin,10 R. Bhathal,11 P. J. Boyce,10 M. J. Drinkwater,12 K. C. Freeman,6 B. K. Gibson,2 A. J. Green,13 R. F. Haynes,1 S. Juraszek,13 M. J. Kesteven,1 P. M. Knezek,14 S. Mader,1 M. Marquarding,1 M. Meyer,5 J. R. Mould,15 T. Oosterloo,16 J. O’Brien,1,6 R. M. Price,7 E. M. Sadler,13 A. Schro¨der,17 I. M. Stewart,17 F. Stootman,11 M. Waugh,1, 5 B. E. Warren,1, 6 R. L. Webster,5 and A. E. Wright1 Received 2002 October 30; accepted 2004 April 7 ABSTRACT We present the HIPASS Bright Galaxy Catalog (BGC), which contains the 1000 H i brightest galaxies in the southern sky as obtained from the H i Parkes All-Sky Survey (HIPASS). The selection of the brightest sources is basedontheirHi peak flux density (Speak k116 mJy) as measured from the spatially integrated HIPASS spectrum. 7 ; 10 The derived H i masses range from 10 to 4 10 M . -

1501.01010V1.Pdf

Draft version January 7, 2015 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 JET-ISM INTERACTION IN THE RADIO GALAXY 3C293: JET-DRIVEN SHOCKS HEAT ISM TO POWER X-RAY AND MOLECULAR H2 EMISSION L. Lanz1, P. M. Ogle1, D. Evans2, P. N. Appleton3, P. Guillard4, B. Emonts5 Draft version January 7, 2015 ABSTRACT We present a 70ks Chandra observation of the radio galaxy 3C 293. This galaxy belongs to the class of molecular hydrogen emission galaxies (MOHEGs) that have very luminous emission from warm molecular hydrogen. In radio galaxies, the molecular gas appears to be heated by jet-driven shocks, but exactly how this mechanism works is still poorly understood. With Chandra, we observe X-ray emission from the jets within the host galaxy and along the 100 kpc radio jets. We model the X-ray spectra of the nucleus, the inner jets, and the X-ray features along the extended radio jets. Both the nucleus and the inner jets show evidence of 107 K shock-heated gas. The kinetic power of the jets is more than sufficient to heat the X-ray emitting gas within the host galaxy. The thermal X-ray and warm H2 luminosities of 3C 293 are similar, indicating similar masses of X-ray hot gas and warm molecular gas. This is consistent with a picture where both derive from a multiphase, shocked interstellar medium (ISM). We find that radio-loud MOHEGs that are not brightest cluster galaxies (BCGs), like 3C 293, typically have LH2 /LX ∼ 1 and MH2 /MX ∼ 1, whereas MOHEGs that are BCGs have LH2 /LX ∼ 0.01 and MH2 /MX ∼ 0.01. -

Radio Sources in Low-Luminosity Active Galactic Nuclei

A&A 392, 53–82 (2002) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20020874 & c ESO 2002 Astrophysics Radio sources in low-luminosity active galactic nuclei III. “AGNs” in a distance-limited sample of “LLAGNs” N. M. Nagar1, H. Falcke2,A.S.Wilson3, and J. S. Ulvestad4 1 Arcetri Observatory, Largo E. Fermi 5, Florence 50125, Italy 2 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA Adjunct Astronomer, Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA e-mail: [email protected] 4 National Radio Astronomy Observatory, PO Box 0, Socorro, NM 87801, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 23 January 2002 / Accepted 6 June 2002 Abstract. This paper presents the results of a high resolution radio imaging survey of all known (96) low-luminosity active galactic nuclei (LLAGNs) at D ≤ 19 Mpc. We first report new 2 cm (150 mas resolution using the VLA) and 6 cm (2 mas resolution using the VLBA) radio observations of the previously unobserved nuclei in our samples and then present results on the complete survey. We find that almost half of all LINERs and low-luminosity Seyferts have flat-spectrum radio cores when observed at 150 mas resolution. Higher (2 mas) resolution observations of a flux-limited subsample have provided a 100% (16 of 16) detection rate of pc-scale radio cores, with implied brightness temperatures ∼>108 K. The five LLAGNs with the highest core radio fluxes also have pc-scale “jets”. -

Astronomy 2008 Index

Astronomy Magazine Article Title Index 10 rising stars of astronomy, 8:60–8:63 1.5 million galaxies revealed, 3:41–3:43 185 million years before the dinosaurs’ demise, did an asteroid nearly end life on Earth?, 4:34–4:39 A Aligned aurorae, 8:27 All about the Veil Nebula, 6:56–6:61 Amateur astronomy’s greatest generation, 8:68–8:71 Amateurs see fireballs from U.S. satellite kill, 7:24 Another Earth, 6:13 Another super-Earth discovered, 9:21 Antares gang, The, 7:18 Antimatter traced, 5:23 Are big-planet systems uncommon?, 10:23 Are super-sized Earths the new frontier?, 11:26–11:31 Are these space rocks from Mercury?, 11:32–11:37 Are we done yet?, 4:14 Are we looking for life in the right places?, 7:28–7:33 Ask the aliens, 3:12 Asteroid sleuths find the dino killer, 1:20 Astro-humiliation, 10:14 Astroimaging over ancient Greece, 12:64–12:69 Astronaut rescue rocket revs up, 11:22 Astronomers spy a giant particle accelerator in the sky, 5:21 Astronomers unearth a star’s death secrets, 10:18 Astronomers witness alien star flip-out, 6:27 Astronomy magazine’s first 35 years, 8:supplement Astronomy’s guide to Go-to telescopes, 10:supplement Auroral storm trigger confirmed, 11:18 B Backstage at Astronomy, 8:76–8:82 Basking in the Sun, 5:16 Biggest planet’s 5 deepest mysteries, The, 1:38–1:43 Binary pulsar test affirms relativity, 10:21 Binocular Telescope snaps first image, 6:21 Black hole sets a record, 2:20 Black holes wind up galaxy arms, 9:19 Brightest starburst galaxy discovered, 12:23 C Calling all space probes, 10:64–10:65 Calling on Cassiopeia, 11:76 Canada to launch new asteroid hunter, 11:19 Canada’s handy robot, 1:24 Cannibal next door, The, 3:38 Capture images of our local star, 4:66–4:67 Cassini confirms Titan lakes, 12:27 Cassini scopes Saturn’s two-toned moon, 1:25 Cassini “tastes” Enceladus’ plumes, 7:26 Cepheus’ fall delights, 10:85 Choose the dome that’s right for you, 5:70–5:71 Clearing the air about seeing vs. -

VLBA Detection of Nuclear Compact Emission in the AGN-Driven Molecular Outflow Candidate NGC 1266

VLBA Detection of Nuclear Compact Emission in the AGN-Driven Molecular Outflow Candidate NGC 1266 Kristina Nyland New Mexico Tech 2012 New Mexico Symposium Outflows in Galaxies • Can help regulate star formation and SMBH growth • May be responsible for various empirical scaling relations in galaxies (e.g., Faber-Jackson relation) • Driving mechanisms: • Stellar feedback • Radiation pressure • Stellar winds (young O stars, AGB stars) • Supernovae • AGNs • Quasar mode (radiative) • Radio mode (mechanical/kinetic) Starburst-Driven Molecular Outflows M82 (Walter+02) Arp 220 (Sakamoto+09) • Prototypical SB galaxy • ULIRG • Interacting with M81 • merger remnant • Molecular gas entrained in • (But AGN may play a starburst wind see role, Rangwala+11) 8 7 • Moutflow = 3 x 10 Msun • Moutflow = 5 x 10 Msun • dM/dt = 30 Msun/year • dM/dt = 100 Msun/year • voutflow = 100 km/s • voutflow = 100 km/s HST HST AGN-Driven Molecular Outflows • Outflows of neutral/ionized gas relatively common in AGNs • Molecular outflows potentially powered by AGNs are rare • Much of the evidence is circumstantial • e.g., SDSS statistical analyses of timing of starbursts and AGN activity • Many candidates for direct evidence are high-redshift quasars • local candidates needed! AGN-Driven Molecular Outflows Mrk 231 (Feruglio+10) • Nearest quasar host • Interacting system 8 • Moutflow = 5.8 x 10 Msun • dM/dt = 100-700 Msun/yr • v = 700 km/s outflow Gemini NGC 1266: Local Candidate AGN- driven Molecular Outflow Host? • Morphology: S0 • Environment: Field – no evidence of recent major merger • Distance: 29.9 Mpc • MK = -22.93 DSS • σ* = 79 km/s 6 • MBH: ~3.2 x 10 Msun IRAM 30m CO Emission Figures from Alatalo et al. -

XXXI. Nuclear Radio Emission in Nearby Early-Type Galaxies

MNRAS 458, 2221–2268 (2016) doi:10.1093/mnras/stw391 Advance Access publication 2016 February 24 The ATLAS3D Project – XXXI. Nuclear radio emission in nearby early-type galaxies Kristina Nyland,1,2‹ Lisa M. Young,3 Joan M. Wrobel,4 Marc Sarzi,5 Raffaella Morganti,2,6 Katherine Alatalo,7,8† Leo Blitz,9 Fred´ eric´ Bournaud,10 Martin Bureau,11 Michele Cappellari,11 Alison F. Crocker,12 Roger L. Davies,11 Timothy A. Davis,13 P. T. de Zeeuw,14,15 Pierre-Alain Duc,10 Eric Emsellem,14,16 Sadegh Khochfar,17 Davor Krajnovic,´ 18 Harald Kuntschner,14 Richard M. McDermid,19,20 Thorsten Naab,21 Tom Oosterloo,2,6 22 23 24 Nicholas Scott, Paolo Serra and Anne-Marie Weijmans Downloaded from Affiliations are listed at the end of the paper Accepted 2016 February 17. Received 2016 February 15; in original form 2015 July 3 http://mnras.oxfordjournals.org/ ABSTRACT We present the results of a high-resolution, 5 GHz, Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array study 3D of the nuclear radio emission in a representative subset of the ATLAS survey of early-type galaxies (ETGs). We find that 51 ± 4 per cent of the ETGs in our sample contain nuclear radio emission with luminosities as low as 1018 WHz−1. Most of the nuclear radio sources have compact (25–110 pc) morphologies, although ∼10 per cent display multicomponent core+jet or extended jet/lobe structures. Based on the radio continuum properties, as well as optical emission line diagnostics and the nuclear X-ray properties, we conclude that the at MPI Study of Societies on June 7, 2016 3D majority of the central 5 GHz sources detected in the ATLAS galaxies are associated with the presence of an active galactic nucleus (AGN). -

The Applicability of Far-Infrared Fine-Structure Lines As Star Formation

A&A 568, A62 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322489 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics The applicability of far-infrared fine-structure lines as star formation rate tracers over wide ranges of metallicities and galaxy types? Ilse De Looze1, Diane Cormier2, Vianney Lebouteiller3, Suzanne Madden3, Maarten Baes1, George J. Bendo4, Médéric Boquien5, Alessandro Boselli6, David L. Clements7, Luca Cortese8;9, Asantha Cooray10;11, Maud Galametz8, Frédéric Galliano3, Javier Graciá-Carpio12, Kate Isaak13, Oskar Ł. Karczewski14, Tara J. Parkin15, Eric W. Pellegrini16, Aurélie Rémy-Ruyer3, Luigi Spinoglio17, Matthew W. L. Smith18, and Eckhard Sturm12 1 Sterrenkundig Observatorium, Universiteit Gent, Krijgslaan 281 S9, 9000 Gent, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] 2 Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle Str. 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 3 Laboratoire AIM, CEA, Université Paris VII, IRFU/Service d0Astrophysique, Bat. 709, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 4 UK ALMA Regional Centre Node, Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK 5 Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 6 Laboratoire d0Astrophysique de Marseille − LAM, Université Aix-Marseille & CNRS, UMR7326, 38 rue F. Joliot-Curie, 13388 Marseille CEDEX 13, France 7 Astrophysics Group, Imperial College, Blackett Laboratory, Prince Consort Road, London SW7 2AZ, UK 8 European Southern Observatory, Karl -

The Low-Metallicity Picture A

Linking dust emission to fundamental properties in galaxies: the low-metallicity picture A. Rémy-Ruyer, S. C. Madden, F. Galliano, V. Lebouteiller, M. Baes, G. J. Bendo, A. Boselli, L. Ciesla, D. Cormier, A. Cooray, et al. To cite this version: A. Rémy-Ruyer, S. C. Madden, F. Galliano, V. Lebouteiller, M. Baes, et al.. Linking dust emission to fundamental properties in galaxies: the low-metallicity picture. Astronomy and Astrophysics - A&A, EDP Sciences, 2015, 582, pp.A121. 10.1051/0004-6361/201526067. cea-01383748 HAL Id: cea-01383748 https://hal-cea.archives-ouvertes.fr/cea-01383748 Submitted on 19 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A&A 582, A121 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526067 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics Linking dust emission to fundamental properties in galaxies: the low-metallicity picture? A. Rémy-Ruyer1;2, S. C. Madden2, F. Galliano2, V. Lebouteiller2, M. Baes3, G. J. Bendo4, A. Boselli5, L. Ciesla6, D. Cormier7, A. Cooray8, L. Cortese9, I. De Looze3;10, V. Doublier-Pritchard11, M. Galametz12, A. P. Jones1, O. Ł. Karczewski13, N. Lu14, and L. Spinoglio15 1 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, UMR 8617, 91405 Orsay, France e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Laboratoire AIM, CEA/IRFU/Service d’Astrophysique, Université Paris Diderot, Bât. -

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC by Paul Dickson Version: 1.4 | March 26, 1997 Copyright °c 1996, by Paul Dickson. All rights reserved If you purchased this book from Paul Dickson directly, please ignore this form. I already have most of this information. Why Should You Register This Book? Please register your copy of this book. I have done two book, SAC's 110 Best of the NGC and the Messier Logbook. In the works for late 1997 is a four volume set for the Herschel 400. q I am a beginner and I bought this book to get start with deep-sky observing. q I am an intermediate observer. I bought this book to observe these objects again. q I am an advance observer. I bought this book to add to my collect and/or re-observe these objects again. The book I'm registering is: q SAC's 110 Best of the NGC q Messier Logbook q I would like to purchase a copy of Herschel 400 book when it becomes available. Club Name: __________________________________________ Your Name: __________________________________________ Address: ____________________________________________ City: __________________ State: ____ Zip Code: _________ Mail this to: or E-mail it to: Paul Dickson 7714 N 36th Ave [email protected] Phoenix, AZ 85051-6401 After Observing the Messier Catalog, Try this Observing List: SAC's 110 Best of the NGC [email protected] http://www.seds.org/pub/info/newsletters/sacnews/html/sac.110.best.ngc.html SAC's 110 Best of the NGC is an observing list of some of the best objects after those in the Messier Catalog. -

Secular Evolution and the Formation of Pseudobulges in Disk Galaxies

5 Aug 2004 22:35 AR AR222-AA42-15.tex AR222-AA42-15.sgm LaTeX2e(2002/01/18) P1: IKH 10.1146/annurev.astro.42.053102.134024 Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2004. 42:603–83 doi: 10.1146/annurev.astro.42.053102.134024 Copyright c 2004 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved First published! online as a Review in Advance on June 2, 2004 SECULAR EVOLUTION AND THE FORMATION OF PSEUDOBULGES IN DISK GALAXIES John Kormendy Department of Astronomy, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712; email: [email protected] Robert C. Kennicutt, Jr. Department of Astronomy, Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721; email: [email protected] KeyWords galaxy dynamics, galaxy structure, galaxy evolution I Abstract The Universe is in transition. At early times, galactic evolution was dominated by hierarchical clustering and merging, processes that are violent and rapid. In the far future, evolution will mostly be secular—the slow rearrangement of energy and mass that results from interactions involving collective phenomena such as bars, oval disks, spiral structure, and triaxial dark halos. Both processes are important now. This review discusses internal secular evolution, concentrating on one important con- sequence, the buildup of dense central components in disk galaxies that look like classical, merger-built bulges but that were made slowly out of disk gas. We call these pseudobulges. We begin with an “existence proof”—a review of how bars rearrange disk gas into outer rings, inner rings, and stuff dumped onto the center. The results of numerical sim- ulations correspond closely to the morphology of barred galaxies. -

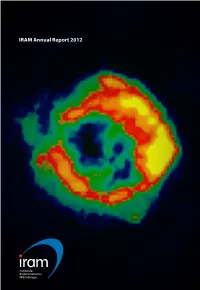

IRAM Annual Report 2012

IRAM IRAM Annual Report 2012 Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique 30-meter diameter telescope, Pico Veleta 6 x 15-meter interferometer, Plateau de Bure The Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM) is a multi-national scientific institute covering all aspects of radio astronomy at millimeter wavelengths: the operation of two high-altitude observatories – a 30-meter diameter telescope on Pico Veleta in the Sierra Nevada (southern Spain), and an interferometer of six 15 meter diameter telescopes on the Plateau de Bure in the French Alps – the development of telescopes and instrumentation, radio astronomical observations and their interpretation. IRAM was founded in 1979 by two national research organizations: the CNRS and the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft – the Spanish Instituto Geográfico IRAM Addresses: Nacional, initially an associate member, became a full member in 1990. Institut de Radioastronomie The technical and scientific staff of IRAM develops instrumentation and Millimétrique 300 rue de la piscine, software for the specific needs of millimeter radioastronomy and for the Saint-Martin d’Hères benefit of the astronomical community. IRAM’s laboratories also supply F-38406 France Tel: +33 [0]4 76 82 49 00 devices to several European partners, including for the ALMA project. Fax: +33 [0]4 76 51 59 38 [email protected] www.iram.fr IRAM’s scientists conduct forefront research in several domains of astrophysics, from nearby star-forming regions to objects at cosmological Observatoire du Plateau de Bure distances. Saint-Etienne-en-Dévoluy