The Iconosphere of Contemporary Terrorism in the Perspective of Visual Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zeller Int All 6P V2.Indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM the FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK

zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM THE FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK A CONTEMPORARY GUIDE TO FIGURE DRAWING, PAINTING, AND COMPOSITION ROBERT ZELLER FOREWORD BY PETER TRIPPI AFTERWORD BY KURT KAUPER MONACELLI STUDIO zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 2-3 11/4/16 12:23 PM Copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER and THE MONACELLI PRESS Illustrations copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER unless otherwise noted Text copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER Published in the United States by MONACELLI STUDIO, an imprint of THE MONACELLI PRESS All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zeller, Robert, 1966– author. Title: The figurative artist’s handbook : a contemporary guide to figure drawing, painting, and composition / Robert Zeller. Description: First edition. | New York, New York : Monacelli Studio, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007845 | ISBN 9781580934527 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Figurative drawing. | Figurative painting. | Human figure in art. | Composition (Art) | BISAC: ART / Techniques / Life Drawing. | ART / Techniques / Drawing. | ART / Subjects & Themes / Human Figure. Classification: LCC NC765 .Z43 2016 | DDC 743.4--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016007845 ISBN 978-1-58093-452-7 Printed in China Design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover illustrations by ROBERT ZELLER Illustration credits appear on page 300. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is dedicated to my daughter, Emalyn. First Edition This book was inspired by Kenneth Clark's The Nude and Andrew Loomis's Figure Drawing for All It's Worth. MONACELLI STUDIO This book would not have been possible without the help of some important peo- THE MONACELLI PRESS 236 West 27th Street ple. -

The Secrets of Pangaea Paintings by James Waller

THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE LOFT GALLERY CLONAKILTY 5 JULY - 4 AUGUST 2018 ORIGIN AND MYTH The Secrets of Pangaea is essentially an exploration of the figure in the landscape and marks James Waller’s first foray into large-scale narrative oil painting, a journey inspired, in large part by the Norwegian master Odd Nerdrum, whom he stud- ied with in August and September 2017. The series revolves around two major compositions, The Children of Lir and The Secrets of Pangaea, and includes smaller works created whilst studying in Norway. The starting points for the major compositions are found in Greek and Irish mythology and include figures in states of both dramatic tension and Arcadian repose. The Secrets of Pangaea recalls the Tahitian paintings of Paul Gauguin, Waller’s first love as a young painter. The brooding sense of melancholy and langour, and the playing of music are symbiotic with Gauguin’s world. The approach to tone and colour, however, are very much informed by his immersion in Odd Nerdrum’s work and the Classical figurative approach. Several other pieces, such as Boy and Moon, Reverie and The Song of Pan- gaea are either derived from or studies for Secrets. Where Secrets only tangentially references Greek figures such as Pan and the Mino- taur, The Children of Lir explicitly references the famous Irish tale of the same name. It does not attempt to illustrate the story, but rather presents both bird and human form together, the human figures in a state of transformative tension, the swans in a state of lateral collapse (death?) and purposeful movement. -

Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2007 And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Perry Walter, "And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2151. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2151 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art and Design East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts by Perry Johnson December 2006 M. Wayne Dyer, Chair Ralph Slatton David Dixon Keywords: painting, alienation, conformity, machine, figurative ABSTRACT And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture by Perry Johnson Man has created vast and powerful systems. These systems and their associated protocols, dogmas, and conventions tend to limit rather than liberate. Evaluation based on homogeneity threatens the devaluation of our humanity. This paper and the artwork it supports examine contemporary culture and its failings in the stewardship of the humanist ideal. -

Title Author Call Number

Art Title Author Call Number Nineteenth century French art : from Romanticism to Impressionism, post- Impressionism and Art Nouveau / Henri Loyrette, general editor ; SeLbastien Allard and Laurence des Cars ; [translated from the French by David Radzinowicz]. Allard, SeLbastien. 709.44034 NIN Brodskaio8 ao8!, N. V. Symbolism / [text: Nathalia BrodskaiLa ; translation Tatyana Shlyak and Rebecca (NatalJ9io8 ao8! Brimacombe]. Valentinovna) 759.057 Essays in migratory aesthetics : cultural practices between migration and art-making / BH301.C92 E87 editors, Sam Durrant, Catherine M. Lord. 2007 China : empire and civilization / edited by Edward L. Shaughnessy. DS706 .C4945 2005 Celts : history and treasures of an ancient civilization / [texts, Daniele Vitali ; translation, Corinne Colette]. Vitali, Daniele. N5925 .V5813 2007 Facts and artefacts : art in the Islamic world : festschrift for Jens KroLger on his 65th birthday / edited by Annette Hagedorn, Avinoam Shalem. N6260 .F27 2007 Renaissance art / [Victoria Charles ; translation, Marlena Metcalf]. Charles, Victoria. N6370 .C4318 2007 N6512.5.P6 M66 Pop art portraits / Paul Moorhouse ; with an essay by Dominic Sandbrook. Moorhouse, Paul. 2007 Complete catalogue of known and documented work by William Merritt Chase (1849- N6537.C464 A4 1916) / Ronald G. Pisano / completed by D. Frederick Baker. Pisano, Ronald G. 2006 Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe Museum collections / Barbara Buhler Lynes. 1942- N6537.O39 A4 2007 Lucian Freud / Sebastian Smee. Smee, Sebastian. N6797.F77 A4 2007 N6921.S6 R358 Renaissance Siena : art for a city / Luke Syson ... [et al.]. 2007 Differencing the canon : feminist desire and the writing of art's histories / Griselda Pollock. Pollock, Griselda. N72.F45 P63 1999 Visual shock : a history of art controversies in American culture / Michael Kammen. -

El Concepto De Sublime, Para Hablar De Religión En La Pintura a Partir Del Siglo XXI

1 El concepto de Sublime, para hablar de religión en la pintura a partir del siglo XXI Francisco Badilla Briones Mestrado em Artes Plásticas – Pintura Faculdade de Belas Artes, Universidade do Porto Orientadora: Doutora, Sofía Torres Gonçalves Porto, 2020 2 “Porque así dijo el Alto y Sublime, el que habita en eternidad, y cuyo nombre es El Santo, que tengo por morada la altura y la santidad” Isaías, 57:15 3 Agradecimientos A todos mis profesores que han sido parte de mi formación en la Faculdade de Belas Artes de la Universidade do Porto A esta maravillosa ciudad de Porto, que desde que llegue me ha acogido con mucho afecto y me ha hecho participe de su energía. 4 RESUMEN La secularización de la sociedad actual desde la ilustración, cambió el mundo en términos filosóficos, hacia un mayor escepticismo y distancia de lo sagrado. El racionalismo, el materialismo y el nihilismo, mostraron una visión diferente de la realidad, reforzando la idea de creer en la razón y en lo que podíamos comprobar empíricamente, dejando en cierto modo de lado las creencias religiosas y aquel sentido mágico en la concepción del mundo. El presente relatório pretende volver la mirada hacia aspectos religiosos y espirituales, empleando como medio la pintura realista del siglo XXI, y las ideas que algunos artistas comparten en relación a aspectos espirituales. El concepto de sublime, será el guía para acercarnos a aquel sentido espiritual en la pintura, primero fue un sentimiento de sublime romántico, con espacios ilimitados, mas tarde la idea de sublime cambio a un concepto mas pesimista y se muestra con incertidumbre en espacios mas cerrados que apelan a la duda y al error, es un sublime con contradicciones, con una mirada distó pica, juntamente con presencia de belleza y placer que nos produce apreciar su lenguaje. -

Gregory Johnson MFA Painting Thesis "Self-Reflexivity Mise En Abîme"

Gregory Nathan Johnson Self-Reflexivity Mise En Abîme Thesis Statement 11/21/11 “In formal Logic, a contradiction is the signal of defeat, but in the evolution of real knowledge it marks the first step in progress towards a victory.” Alfred North Whitehead Two things drive my studio work. The first is the never-ending quest to paint an oily surface that intrigues me. The second is my interest in self-reflexivity. The first provides me with an elusive goal to help my skill in painting develop and the second is full of contradictions and enigmas to ruminate upon. I like to break down my inspirations into the physicality of paint and abstract thoughts. It has a ring of dualism between the body and mind. Yet, I say: first the surface, second the concept. Am I creating a hierarchy of body over mind? Or am I implying a causal relationship that forms the embodied mind as described by George Lakoff. Perhaps I agree with the later without dismissing the former. One thing I do know is that my thought process is causal; one thought leads to the next as it examines the thoughts that came before. For this reason I will present my thesis in a narrative form, describing my research through selected works in a chronological order. I will start with my so called “first drive” of technique. Technique “The moment a man begins to talk about technique that's proof that he is fresh out of ideas.” Raymond Chandler “The fun of painting is technique: loose opposite tight, texture versus wash, light against dark.” Joe Garcia Though Raymond Chandler may be expressing a phenomenon that plays out often in “Kitschy” works, I dare not underplay the force inherent in technique and the physical makeup of a painting. -

Resurrection Robert David Jinkins Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2018 Resurrection Robert David Jinkins Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Esthetics Commons Recommended Citation Jinkins, Robert David, "Resurrection" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16724. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16724 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Resurrection by Robert Jinkins A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ART Major: Integrated Visual Art Program of Study Committee: Brent Holland, Major Professor Barbara Walton Barbara Haas The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2018 Copyright © Robert Jinkins, 2018. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to Andrew Wyeth, Albrecht Dürer, and Rembrandt. All three of these guys are better than I am and never wrote a thesis. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. v ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

Education Solo Exhibitions

David Molesky (b.1977) is an internationally recognized oil painter known for his landscapes and figurative works. EDUCATION 1992-1995 Studied w/ Plein Air Painter, Walter Bartman 1994 Summer College Cornell University 1997 Fall Semester, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 1995-1999 B.A. University of California at Berkeley Study with Wendy Sussman, Katherine Sherwood, and Richard Shaw Also premed with emphasis in Neurobiology 2000 San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA 2004-2006 visits to David Ligare’s studio, Salinas, California 2006-2008 Apprentice to Odd Nerdrum, Iceland and Norway SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Riot, Stephen Romano Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2015 Riot, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 2014 Riot, the fridge, Washington, D.C. Calm and Unrest, Copro Gallery, Santa Monica, CA 2013 A Long Moment, a.Muse Gallery, San Francisco, CA (catalog) 2012 AIR/WATER, the fridge, Washington, D.C. 2011 Protean Dreams, Artspace 712, San Francisco, CA (catalog) A Journey Back, 12 Gallagher Lane, San Francisco, CA www.DavidMolesky.com Eclipse of an Undercurrent, Marjorie Evans Gallery, Sunset Cultural Center, Carmel, CA (Two-man Exhibition) Smoke, Basement Gallery, Oakland, CA 2010 Turbulent Mirror, Rae Douglass Gallery, Berkeley, CA Spume, Canessa Gallery, San Francisco, CA (catalog) 2007 (Two-man Exhibition) Equinox, Terrence Rogers Fine Art, Santa Monica, CA (Two-man Exhibition) Jan-Ove Tuv and David Molesky. Radhus, Tonsberg, Norway 2005 Recent Landscapes, Las Fuentas Villa, Carmel Valley, -

Tenebrism in the Painting of Odd Nerdrum from 1983 to 2004 Master

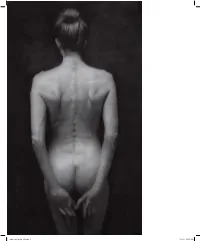

Tenebrism in the painting of Odd Nerdrum from 1983 to 2004 by JOHAN CONRADIE 22359363 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the subject Master of Arts in Fine Arts in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA OCTOBER 2006 Study Leader: Dr E Dreyer This essay is subject to regulation G.35 of the University of Pretoria and may in no circumstances be reproduced as a whole or in part without a written consent of the University. Declaration I declare that the writing and technical production of Tenebrism in the painting of Odd Nerdrum from 1983 to 2004 is entirely my own work. All the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete referencing. Should the dissertation or sections from the dissertation be quoted or referred to in any form this must be acknowledged in full. This mini-dissertation is the copyrighted property of the University of Pretoria. It may not be reproduced or copied in any form. Signed: Johan Conradie, on this thirty first day of October 2006. Summary The hypothesis of this dissertation is that contemporary Norwegian painter, Odd Nerdrum (b 1944), uses tenebrism as a mode of beauty and a device to emphasise psychological states of being. Tenebrism is an effective kitsch device to create an impression of realism and so-called truthfulness while pointing to the deepest human sentiments and emotions. I argue that Nerdrum’s tenebrist art questions dark truths about modernity and its effect on the self. The darkness of his tenebrist style amplifies the emotional states of his human characters, and becomes a negative form of transcendence into absence and the power of its nothingness. -

Visual Arts Center of New Jersey Exhibition Timeline

VISUAL ARTS CENTER OF NEW JERSEY EXHIBITION TIMELINE 1935 Exhibition Committee Chairperson: Junius Allen (Fall 1935 – Spring 1936) Oil and Watercolor Paintings by Carl Sprinchorn October 27 – November 9, 1935 3rd Annual Exhibition and Auction December 2 – 14, 1935 1936 Exhibition Committee Chairperson: Junius Allen (Fall 1935 – Spring 1936) Unknown (Fall 1936 – Spring 1937) Paintings by New York Artists: George Elmer Browne, John F. Carlson, George Pearse Ennis, Andrew Winter, Ernest Roth, and Ferdinand E. Warren January 20 – February 1, 1936 Offsite Exhibition: Summit Artists at the Summit Public Library February 16 – 29, 1936 Contemporary Prints October 18 – unknown date, 1936 Recent Paintings by Junius Allen November 8 – unknown date, 1936 1937 Paintings by Modern Artists of New Jersey January 3 – unknown date, 1937 Paintings, Drawings, and Prints by Fiske Boyd January 24 – unknown date, 1937 Antique Pictures and Early American Art from Private Collections March 14 – unknown date, 1937 Contemporary Prints October 18 – unknown date, 1937 Etchings and Dry Point Prints from Collections of Summit Residents November 7 – 24, 1937 1938 Oil and Pastel Paintings by Mary Bayne Bugbird January 9 – 26, 1938 Paintings from the Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art January 30 – February 16, 1938 Photography by Summit Residents February 20 – March 9, 1938 Oil and Watercolor Paintings by Lesley Crawford March 13 – 30, 1938 Work of the Life Class April 24 – May 11, 1938 1939 Martha Berry, Art Director at Summit Public Schools Unknown date, 1939 Claire Boyd, Art Instructor at Kent Place School Unknown date, 1939 Collection of Bound Books Unknown date, 1939 New Jersey Painters: Junius Allen, T. -

Dag Solhjell the Defeat of the Curatoriat Odd Nerdrum

l Odd Nerdrum (1944) paints in the tra- 3. THE ELITARIAN ART GAME dag solhjell dition of Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Among contemporary Norwegian artists, his In countries with a cultural policy name is today the most widely known. His based on the principle of arm-length dis- paintings draw the largest audiences and tance between politics and art, the distrib- the defeat of the sell at the highest prices when they are ution of these two assets is left to the art exhibited. In 1998 he declared himself not world alone. The result is an extremely curatoriat to be an artist but a kitsch painter, and uneven distribution of the assets: most named his paintings kitsch. This paper players end up with few assets, while a odd nerdrum - studies the game of symbolic power around small elite ends up with most of it. On the this instance of cultural disorder - or is it surface, the ethic of the elitarian game a case study of the order? appears to be: winner takes all. The It is often useful, if we say to ourselves American and French art games are elitari- aquisition and use while philosophizing: to name something, an in this sense. is like putting a name label on a thing. of symbolic power Wittgenstein. 4. THE EGALITARIAN ART GAME 1. THE ART WORLD AS A GAME In Norway and other social-democratic countries, cultural policy is egalitarian and The art world - in the philosophical welfare oriented. Their governments take sense of Arthur Danto and in the sociologi- steps to level out the unequal distribution of cal sense of Pierre Bourdieu and Howard S. -

My Experience at Nerdrum School by Macarena Asensio [email protected]

My experience at Nerdrum School By Macarena Asensio [email protected] As I sat next to Turner on the plane I knew that the adventure had begun in the best way. Being able to study in Nerdrum School was a great distant dream. Slowly this dream was getting closer and closer to reality. Thanks to all those who supported me, the residence with the painter Sebastián Salvo and my dear Argentinian painting teacher Roberto Pedro Gatti. Thanks to Odd Nerdrum and his family, who generously open their doors to make Book that I borrowed from the woman who was sitting next to me, talked to me almost the entire flight duration this possible. from Buenos Aires to Copenhagen. For all of those who would like to apply for the school, I will tell you more about my experience and what I was doing during these months. Student’s studio, Memorosa (Norway). A good ground According Odd Nerdrum, the most important thing you can learn in Nerdrum School is preparing the canvas and philosophy. He arrived to this recipe after many tests and failings, including the ruining of paintings that then he decided to remake. Learning to do this priming was like learning to cook the most difficult cake. We had to observe a lot, try, ruin fabrics, feel the ideal consistency, the sense and rhythm of the spatula, and try again... until we succeeded, and in the end it was so easy! Philosophy challenges us and directs our movement in doing. Many times we use words and repeat phrases that we believe to be our own.