Tenebrism in the Painting of Odd Nerdrum from 1983 to 2004 Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zeller Int All 6P V2.Indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM the FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK

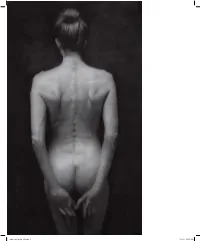

zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM THE FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK A CONTEMPORARY GUIDE TO FIGURE DRAWING, PAINTING, AND COMPOSITION ROBERT ZELLER FOREWORD BY PETER TRIPPI AFTERWORD BY KURT KAUPER MONACELLI STUDIO zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 2-3 11/4/16 12:23 PM Copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER and THE MONACELLI PRESS Illustrations copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER unless otherwise noted Text copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER Published in the United States by MONACELLI STUDIO, an imprint of THE MONACELLI PRESS All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zeller, Robert, 1966– author. Title: The figurative artist’s handbook : a contemporary guide to figure drawing, painting, and composition / Robert Zeller. Description: First edition. | New York, New York : Monacelli Studio, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007845 | ISBN 9781580934527 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Figurative drawing. | Figurative painting. | Human figure in art. | Composition (Art) | BISAC: ART / Techniques / Life Drawing. | ART / Techniques / Drawing. | ART / Subjects & Themes / Human Figure. Classification: LCC NC765 .Z43 2016 | DDC 743.4--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016007845 ISBN 978-1-58093-452-7 Printed in China Design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover illustrations by ROBERT ZELLER Illustration credits appear on page 300. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is dedicated to my daughter, Emalyn. First Edition This book was inspired by Kenneth Clark's The Nude and Andrew Loomis's Figure Drawing for All It's Worth. MONACELLI STUDIO This book would not have been possible without the help of some important peo- THE MONACELLI PRESS 236 West 27th Street ple. -

Maurice-Quentin De La Tour

Neil Jeffares, Maurice-Quentin de La Tour Saint-Quentin 5.IX.1704–16/17.II.1788 This Essay is central to the La Tour fascicles in the online Dictionary which IV. CRITICAL FORTUNE 38 are indexed and introduced here. The work catalogue is divided into the IV.1 The vogue for pastel 38 following sections: IV.2 Responses to La Tour at the salons 38 • Part I: Autoportraits IV.3 Contemporary reputation 39 • Part II: Named sitters A–D IV.4 Posthumous reputation 39 • Part III: Named sitters E–L IV.5 Prices since 1800 42 • General references etc. 43 Part IV: Named sitters M–Q • Part V: Named sitters R–Z AURICE-QUENTIN DE LA TOUR was the most • Part VI: Unidentified sitters important pastellist of the eighteenth century. Follow the hyperlinks for other parts of this work available online: M Matisse bracketed him with Rembrandt among • Chronological table of documents relating to La Tour portraitists.1 “Célèbre par son talent & par son esprit”2 – • Contemporary biographies of La Tour known as an eccentric and wit as well as a genius, La Tour • Tropes in La Tour biographies had a keen sense of the importance of the great artist in • Besnard & Wildenstein concordance society which would shock no one today. But in terms of • Genealogy sheer technical bravura, it is difficult to envisage anything to match the enormous pastels of the président de Rieux J.46.2722 Contents of this essay or of Mme de Pompadour J.46.2541.3 The former, exhibited in the Salon of 1741, stunned the critics with its achievement: 3 I. -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

ARTS 5306 Crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art History Fall 2020

ARTS 5306 crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art HIstory fall 2020 Instructor: Jill Carrington [email protected] tel. 468-4351; Office 117 Office hours: MWF 11:00 - 11:30, MW 4:00 – 5:00; TR 11:00 – 12:00, 4:00 – 5:00 other times by appt. Class meets TR 2:00 – 3:15 in the Art History Room 106 in the Art Annex and remotely. Course description: European art from 1600 to 1750. Prerequisites: 6 hours in art including ART 1303 and 1304 (Art History I and II) or the equivalent in history. Text: Not required. The artists and most artworks come from Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth Century Art and Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2e, 2008 or 1e, 2005. One copy of the 1e is on four-hour reserve in Steen Library. Used copies of the both 1e and 2e are available online; for I don’t require you to buy the book; however, you may want your own copy or share one. Objectives: .1a Broaden your interest in Baroque art in Europe by examining artworks by artists we studied in Art History II and artists perhaps new to you. .1b Understand the social, political and religious context of the art. .2 Identify major and typical works by leading artists, title and country of artist’s origin and terms (id quizzes). .3 Short essays on artists & works of art (midterm and end-term essay exams) .4 Evidence, analysis and argument: read an article and discuss the author’s thesis, main points and evidence with a small group of classmates. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

Chapter 25 Baroque

CHAPTER 25 BAROQUE Flanders, Dutch Republic, France,,g & England Flanders After Marti n Luth er’ s Re forma tion the region of Flanders was divided. The Northern half became the Dutch Republic, present day Holland The southern half became Flanders, Belgium The Dutch Republic became Protestant and Flanders became Catholic The Dutch painted genre scenes and Flanders artists painted religious and mythol ogi ca l scenes Europe in the 17th Century 30 Years War (1618 – 1648) began as Catholics fighting Protestants, but shifted to secular, dynastic, and nationalistic concerns. Idea of united Christian Empire was abandoned for secu lar nation-states. Philip II’s (r. 1556 – 1598) repressive measures against Protestants led northern provinces to break from Spain and set up Dutch Republic. Southern Provinces remained under Spanish control and retained Catholicism as offiilfficial re liiligion. PlitildititiPolitical distinction btbetween HlldHolland an dBlid Belgium re fltthiflect this or iiigina l separation – religious and artistic differences. 25-2: Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross, 1610-1611, oil on Cue Card canvas, 15 X 11. each wing 15 X 5 • Most sought a fter arti st of hi s time - Ambassador, diplomat, and court painter. •Paintinggy style •Sculptural qualities in figures •Dramatic chiaroscuro •Color and texture like the Venetians • Theatrical presentation like the Italian Baroque •Dynamic energy and unleashed passion of the Baroque •Triptych acts as one continuous space across the three panels. •Rubens studied Renaissance and Baroque works; made charcoal drawings of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and the Laocoon and his 2 sons. •Shortly after returning home , commissioned by Saint Walburga in Antwerp to paint altarpiece – Flemish churches affirmed their allegiance to Catholicism and Spanish Hapsburg role after Protestant iconoclasm in region. -

The Secrets of Pangaea Paintings by James Waller

THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE LOFT GALLERY CLONAKILTY 5 JULY - 4 AUGUST 2018 ORIGIN AND MYTH The Secrets of Pangaea is essentially an exploration of the figure in the landscape and marks James Waller’s first foray into large-scale narrative oil painting, a journey inspired, in large part by the Norwegian master Odd Nerdrum, whom he stud- ied with in August and September 2017. The series revolves around two major compositions, The Children of Lir and The Secrets of Pangaea, and includes smaller works created whilst studying in Norway. The starting points for the major compositions are found in Greek and Irish mythology and include figures in states of both dramatic tension and Arcadian repose. The Secrets of Pangaea recalls the Tahitian paintings of Paul Gauguin, Waller’s first love as a young painter. The brooding sense of melancholy and langour, and the playing of music are symbiotic with Gauguin’s world. The approach to tone and colour, however, are very much informed by his immersion in Odd Nerdrum’s work and the Classical figurative approach. Several other pieces, such as Boy and Moon, Reverie and The Song of Pan- gaea are either derived from or studies for Secrets. Where Secrets only tangentially references Greek figures such as Pan and the Mino- taur, The Children of Lir explicitly references the famous Irish tale of the same name. It does not attempt to illustrate the story, but rather presents both bird and human form together, the human figures in a state of transformative tension, the swans in a state of lateral collapse (death?) and purposeful movement. -

Baroque Paintings Tend to Privilege Emotional Intensity Over Rationality and Frequently Use Rich Colours and Intense Contrasts of Light and Dark (Tenebrism)

SESSION 5 (Tuesday 5th February 2019) 17th Century Baroque 1. Michelangelo da Caravaggio [MA] 1.1. The Calling of St Matthew 1598-1601 1.2. The Madonna of Lereto 1604 2. Peter Paul RuBens [FB] 2.1. Sampson & Delilah 2.2. The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus 1618 Oil on canvas (224 x 209cm) 3. Van Dyck [FB] 3.1. Charles I of England 1636 4. Artemesia Gentileschi 4.1. Judith Slaying Holofernes 1612 5. Diego de Velazquez [BA]. 5.1. Las Meninas 1656 canvas (323 x 276cm) Prado, Madrid 6. Nicolas Poussin [BA] 6.1. Landscape with Orpheus and Euridice 1650 Louvre, Oil on canvas (124 x 200cm) 6.2. Et in Arcadia Ego 1638 Oil on canvas (87 x 120cm) Louvre. Also see Arcadian Shepherds 1627 Chatsworth House 7. Claude Lorrain 7.1. The Judgement of Paris 7.2. Seaport at Sunset , 1648, Louvre Also see Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire 1839 National Gallery Title page: Artemisia Gentileschi ‘Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting’ 1638 Royal Collection Baroque paintings tend to privilege emotional intensity over rationality and frequently use rich colours and intense contrasts of light and dark (teneBrism). Often the paintings catch a moment in the action, and the oBserver’s perspective is so close to the events they might almost feel a participant. The Council of Trent (1545-63) was set up By Pope Paul III to counter the influence of the Protestant churches. The Council called for Church commissioned paintings to have emotional appeal and a clear religious narrative and message, rejecting the more stylistic affectations of Mannerism, so Baroque paintings fitted that brief well. -

Rembrandt's 1654 Life of Christ Prints

REMBRANDT’S 1654 LIFE OF CHRIST PRINTS: GRAPHIC CHIAROSCURO, THE NORTHERN PRINT TRADITION, AND THE QUESTION OF SERIES by CATHERINE BAILEY WATKINS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 ii This dissertation is dedicated with love to my children, Peter and Beatrice. iii Table of Contents List of Images v Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historiography 13 Chapter 2: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and the Northern Print Tradition 65 Chapter 3: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interest in Tone 92 Chapter 4: The Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus and Rembrandt’s Techniques for Producing Chiaroscuro 115 Chapter 5: Technique and Meaning in the Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus 140 Chapter 6: The Question of Series 155 Conclusion 170 Appendix: Images 177 Bibliography 288 iv List of Images Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Presentation in the Temple, c. 1654 178 Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1950.1508 Figure 2 Rembrandt, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654 179 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, P474 Figure 3 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 180 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.5 Figure 4 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 181 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1922.280 Figure 5 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 182 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.4 Figure 6 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 183 London, The British Museum, 1973,U.1088 Figure 7 Albrecht Dürer, St. -

Original Neurology and Medicine in Baroque Painting

Original Neurosciences and History 2017; 5(1): 26-37 Neurology and medicine in Baroque painting L. C. Álvaro Department of Neurology, Hospital de Basurto. Bilbao, Spain. Department of Neurosciences, Universidad del País Vasco. Leoia, Spain. ABSTRACT Introduction. Paintings constitute a historical source that portays medical and neurological disorders. e Baroque period is especially fruitful in this respect, due to the pioneering use of faithful, veristic representation of natural models. For these reasons, this study will apply a neurological and historical perspective to that period. Methods. We studied Baroque paintings from the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, and the catalogues from exhibitions at the Prado Museum of the work of Georges de La Tour (2016) and Ribera (Pinturas [Paintings], 1992; and Dibujos [Drawings], 2016). Results. In the work of Georges de La Tour, evidence was found of focal dystonia and Meige syndrome ( e musicians’ brawl and Hurdy-gurdy player with hat), as well as de ciency diseases (pellagra and blindness in e pea eaters, anasarca in e ea catcher). Ribera’s paintings portray spastic hemiparesis in e clubfoot, and a complex endocrine disorder in the powerfully human Magdalena Ventura with he r husband and son. His drawings depict physical and emotional pain; grotesque deformities; allegorical gures with facial deformities representing moral values; and drawings of documentary interest for health researchers. Finally, Juan Bautista Maíno’s depiction of Saint Agabus sho ws cervical dystonia, reinforcing the compassionate appearance of the monk. Conclusions. e naturalism that can be seen in Baroque painting has enabled us to identify a range of medical and neurological disorders in the images analysed. -

The Art Market in 2020 04 EDITORIAL by THIERRY EHRMANN

The Art Market in 2020 04 EDITORIAL BY THIERRY EHRMANN 05 EDITORIAL BY WAN JIE 07 GEOGRAPHICAL BREAKDOWN OF THE ART MARKET 15 WHAT’S CHANGING? 19 ART BEST SUITED TO DISTANCE SELLING 29 WHO WAS IN DEMAND IN 2020? AND WHO WASN’T? 34 2020 - THE YEAR IN REVIEW 46 TOP 500 ARTISTS BY FINE ART AUCTION REVENUE IN 2020 Methodology The Art Market analysis presented in this report is based on results of Fine Art auctions that oc- cured between 1st January and 31st December 2020, listed by Artprice and Artron. For the purposes of this report, Fine Art means paintings, sculptures, drawings, photographs, prints, videos, installa- tions, tapestries, but excludes antiques, anonymous cultural goods and furniture. All the prices in this report indicate auction results – including buyer’s premium. Millions are abbreviated to “m”, and billions to “bn”. The $ sign refers to the US dollar and the ¥ sign refers to the Chinese yuan. The exchange rate used to convert AMMA sales results in China is an average annual rate. Any reference to “Western Art” or “the West” refers to the global art market, minus China. Regarding the Western Art market, the following historical segmentation of “creative period” has been used: • “Old Masters” refers to works by artists born before 1760. • “19th century” refers to works by artists born between 1760 and 1860. • “Modern art” refers to works by artists born between 1860 and 1920. • “Post-war art” refers to works by artists born between 1920 and 1945. • “Contemporary art” refers to works by artists born after 1945. -

Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2007 And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Perry Walter, "And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2151. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2151 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art and Design East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts by Perry Johnson December 2006 M. Wayne Dyer, Chair Ralph Slatton David Dixon Keywords: painting, alienation, conformity, machine, figurative ABSTRACT And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture by Perry Johnson Man has created vast and powerful systems. These systems and their associated protocols, dogmas, and conventions tend to limit rather than liberate. Evaluation based on homogeneity threatens the devaluation of our humanity. This paper and the artwork it supports examine contemporary culture and its failings in the stewardship of the humanist ideal.