Zeller Int All 6P V2.Indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM the FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A DIY Approach: Creating Access to Home Movie Excerpts Documenting the Art & Life of Kent Bellows

A DIY Approach: Creating Access to Home Movie Excerpts Documenting the Art & Life of Kent Bellows by David I. Griess A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program Department of Cinema Studies New York University May 2021 2 I was hesitant to reenter the United States educational system since graduating from undergrad in fall of 2007. Now that I have, my time spent at NYU has served as a lesson and a reminder to be a little more kind to myself and to value my abilities. “I THINK IN PICTURES. Words are like a second language to me. I translate both spoken and written words into full-color movies, complete with sound, which run like a VCR tape in my head.” Temple Grandin, Thinking in Pictures My Life with Autism, 1995, 2006 3 Acknowledgements Thank you to my thesis advisor, Juana Suárez, Associate Arts Professor/Director of NYU MIAP. Thank you, artist Joey Skaggs and Judy Drosd, Film Producer and Archive Manager of The Joey Skaggs Collection, for your inspiration, encouragement, and trust to work remotely with your collection in the summer of 2020. Thank you, Siobhan Hagan, CEO of MARMIA, for your knowledge, guidance, and enthusiasm during my fall 2020 internship with the Mid- Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive. Thank you to Jim and Robin Griess for your love, encouragement, and support throughout my life. Thank you to Phyllis Bellows for your love, support, grace, and strength. Your life is truly an inspiration. Thank you to my life partner Elizabeth Lamb for your continued and unwavering emotional and moral support. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Virtual Día De Los Muertos Nov. 1

It's Wednesday, October 28. In today's issue: Día de los Muertos; women, voting, and drinking; re-imagining historic posters; historic site seasonal hours; expedition archeology; 1920s Wayne hospital radio station; swabbing the decks of the USS Missouri. Virtual Día de los Muertos Nov. 1 2 Experience the excitement and discover the meaning of El Día de los Muertos, (the Day of the Dead), virtually. The 2020 Day of the Dead will be celebrated in Lincoln with ofrendas (traditional memorial displays) at the Nebraska History Museum and Bennett Martin Public Library. We're asking you to participate in this year's ofrenda by providing a story of a passed loved one you wish to remember. Keep reading. Don’t let women vote if you want to keep drinking! 3 If you let women vote, will they take away your beer? There was a time when many Nebraska men feared their wives and daughters would do just that. Traditional-minded men feared that politically active women would drive them to drink—and then prevent them from drinking. Nebraska’s brewers, distillers, and saloon owners financially supported anti-suffrage efforts in order to stop Prohibition in Nebraska. Keep reading. History Nebraska and Nebraska Arts Council invite artists to re-imagine historic posters Nebraska has a long history of circulating posters encouraging social action, particularly during years of intense change. Recognizing that 2020 is also a year of change, History Nebraska, in partnership with the Nebraska Arts Council, invited ten Nebraska artists to continue this tradition. Using historic posters from History Nebraska’s collection as inspiration, artists created their own posters to address today’s themes, including (but not limited to) COVID-19, economic hardship, equality, racial injustice, and voter 4 participation. -

LEGS’ DIAMOND, Stances Affecting Nationad Invest Through Constructive Financing Amd Berlin, Oct

? .■ '-^2 ^ r -1% V' -i Y rrS. I 't - It -S »• f T -4 — jf* f ♦ • r'«t" v>'“' ' . MSVIVBBSmiN 4« » Va >» •^ii* iv 1 A/ A fVUtifeL DAILY GISGULATIOV JV-s* for'tiie Month of September, 1 9 S0 I.... p.. ■ Innrsis tng - sjowdlBest, a et .«a^i^. ;’, V- *a.»2u V so tool jm ibalU fy :>*' •“V b y sbowen Me ionMit or Tnes* I v., c IW'‘.iTir- Members of the Audit Barean Vf, vT- , , of OrenlsSons.' u C ,h •» . t »J» * • •.• . - . j i ’A. ‘ »_________ . ................l>’^ -3' m'K- ^ lW’"i;, ~ ■. '•WiE.WsiLfS +■ I O f , ■» •* , -V t. #. —_ S O C tH ^ lilO|911i)cY, OC?rOMR .13, 1030. •hVBILVB ?A €jB r ‘ PRICE THBIIE C E N lt 1:^4 , yOL. XLV., NO. 11. (Oassilled AdrertlBins on Page It) u*s- 1 rS-T? V- WEATHER MAPS TALCOTTVILIl NEW INVENTION T he.M enacing: M uzzlie of ^.IJnele San»?i * rest G iin Atlantic Skippers May Now HANISKILtED Know Conditions All Alongr the Ocean Routes. ^ '• iimM'm- GOINGJOWORK New York, Oct. 13—(AP)— Samples of a north Atlantic weather map which would en able ship captains to tell at a glance toe weather conditions John McKofle Meets Death at any point in their course Fascists' WiMbws, were brought back to New York today by Charles J. Pan- Instantly When Hit by nill, vice president of toe Radio- Distege Pistols and mtuine Corporation. He has been arranging with weather Automobile Driven by bureaus abroad for co-operation F^kt on Streets — hside in preparing toe service. -

Lord Spencer to Highlight Benefit Gala

Vol.1 No.3 Summer 2008 Lord Spencer to Highlight Benefit Gala celebration of art, history and friendship that Aspans the Atlantic Ocean will be renewed when Studio Incamminati hosts Charles Edward Maurice, the Ninth Earl Spencer, for a benefit gala Sept. 12 at The Union League of Philadelphia. Nelson Shanks, Studio Incamminati founder and artistic director, painted portraits of Lord Spencer and his sister Princess Diana that still hang in the family home, Althorp. The dinner event will feature Lord Spencer’s reminiscences, “Growing Up at Althorp,” the magnificent estate that celebrates its 500th anniversary this year. In addition, Nelson Shanks will share his memories of “Painting Princess Diana.” An exhibition of sketches and photos of Diana, from Shanks’ private archives, also will be on display. In keeping with the British theme, selections from the Gilbert and Sullivan songbook will provide the entertainment. M Althorp, the Spencer family home since 1508, sits on 14,000 acres of English countryside. L Lord Spencer speaks about “Growing Up at Althorp,” at L Nelson Shanks will share memories of his time spent the September benefit gala. painting Diana. A Rare Friendship Provides a Memorable Evening e are so excited and honored to have great friendship that continues today. This gala will provide a rare opportunity to WCharles Edward Maurice, the Ninth Earl Most of us remember the moment when we meet Lord Spencer and understand what it was like Spencer, come to Philadelphia for our special first heard the tragic news of Princess Diana’s growing up with Diana at Althorp. Nelson will gala on Sept. -

Kate Sammons U Expect the Unexpected

8 Kate Sammons u Expect the Unexpected by Molly Siple Self-portrait step in closely and see the painting on an intimate scale. I want Oil on panel 200 3 160 them to feel the sensation of drifting with the waves and to Collection of the Artist smile at the thought of floating along with eels.” Another painting that she daydreamed her way into ate Sammons is a delightful bundle of is Stairs and Flowers. “I found this mass of flowers to be energy who brings an exacting and inquisitive mind the perfect fertile area to get lost in,” says Sammons. She Kto her masterful work as an artist. Trained classically graphically makes the point by adding surreal stairs and a and drawing inspiration from the arts of the Renaissance, doorway to the composition, the flowers acting as an entry Sammons is known for her exquisitely rendered still life and point into her mental wanderings. This painting is especially portraiture. But most interestingly, she bravely steps away from interesting as it features both Sammons’ classical rendering typical versions of these, inventing her own intriguing imagery. skills and her freer handling with pigment and form— “I am trained as a realist painter and have a very academic demonstrating control, plus spontaneity. “I could have been background,” explains Sammons, “but these days I find myself a middle child,” Sammons says, “since I’m always trying to longing to reach into the subconscious and dreams and balance different elements and find ways to compromise. The memories for subject matter. You know when you see something just on the edge of your vision…almost like one of those floaters you can see in your eye… the ideas I have for a painting are almost like these. -

S U M M E R 2019

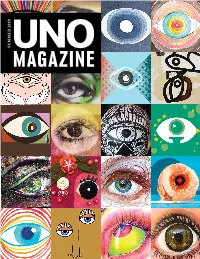

SUMMER 2019 Today is the day to stop saying “someday.” Felicia Webb, Graduate Social Gerontology, BGS & Master’s University of Nebraska at Omaha My today started when I realized dreams don’t have a time limit. At 48 years old, I decided to go back to school. As soon as I reached out to the University of Nebraska at Omaha they grabbed my hand. The professors were all willing to help. Before, I thought my education was something I couldn’t attain. I was busy trying to make a living; I wasn’t smart enough. But one day I felt smart enough to try and never looked back. With my online program I felt like I was in classroom with other classmates, but from within the four walls of my home. I did my schoolwork everywhere: airports, traveling, at home. Wherever I was, I was walking into a classroom and never felt alone. The impact of the people I’ve never met face to face is just as strong as if I’d stood there and shook their hands. 125+ online programs. online.nebraska.edu SUMMER 2019 IN EVERY ISSUE 4 From the Chancellor 10 5 Letters to the Editor 6 From the Editor 7 Alumni Association 22 10 Philanthropy Matters 14 The Colleges 20 Athletics 26 52 Class Notes 55 Future Alums 56 Sights & Sounds 58 For Fun 30 FEATURES 22 Getting Serious About Comics 38 26 Walking Works of Art 30 Art House 38 Witness 42 Art of Preservation 46 46 Artists at Work SUMMERVOL. 10, NO. 2 www.unoalumni.org/unomag UNO MAGAZINE is a publication of the University of Nebraska at Omaha, the UNO Alumni Association and the University of Nebraska Foundation. -

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery News Winter/Spring 2008 from the Acting Director

PROFILESmithsonian National Portrait Gallery News Winter/Spring 2008 From the Acting Director Over Presidents’ Day weekend, nearly 25,000 peo- Steichen: Portraits” pre- ple visited the Donald W. Reynolds Center. I would sents celebrity photo- like to think that what motivated so many to come graphs that complement Ken Rahaim to the museums at Gallery Place was the National those of the less-well-known Zaida Ben-Yusuf—the Portrait Gallery’s permanent collection, which is subject of the groundbreaking loan show “Zaida currently enhanced by the loan of Charles Willson Ben-Yusuf: New York Portrait Photographer.” If Peale’s splendid 1779 portrait of George Washing- you traveled to the National Portrait Gallery twice, ton after the Battle of Princeton. This iconic por- once in the winter and again in late spring, you trait of the triumphant General Washington com- would have seen “The Presidency and the Cold plements our own equally iconic “Lansdowne” War” and its replacement, “Herblock’s Presidents: portrait of Washington as president, completed by ‘Puncturing Pomposity,’” which takes a less-than- Gilbert Stuart in 1796. Both of these imposing por- reverential look at those who occupy our nation’s traits, which represent the cornerstones of Wash- highest office. Two one-person shows have also been ington’s career, were initially destined for European big draws: “KATE: A Centennial Celebration,” il- collections: Peale’s portrait was sent to Spain the luminates moments in the life of Katharine Hep- year it was completed, and Stuart’s portrait was a burn, while Stephen Colbert’s portrait, displayed gift to Lord Lansdowne, an English supporter of over the water fountains between the second-floor the American Revolution. -

Canadian Philatelist Philatéliste Canadien

The Canadian Philatelist Le Philatéliste canadien September/October 2008 septembre/octobre - VOL. 59 • NO.5 PM40069611 $5.00 R 9828 5,00$ Journal of THE ROYAL PHILATELIC SOCIETY OF CANADA Revue de LA SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE DE PHILATÉLIE DU CANADA Canadians in Les Canadiens Hollywood: à Hollywood, The Sequel la suite Four more Canadians who made it big in Ce jeu de timbres met en vedette Hollywood—Marie Dressler, Raymond Burr, quatre autres Canadiens qui ont brillé Norma Shearer and Chief Dan George— dans l’exercice de leur art à Hollywood : star on this classic quartet of stamps. Marie Dressler, Raymond Burr, Norma Shearer et le chef Dan George. Don’t miss this exciting sequel. Buy your stamps and collectibles today. Ne ratez pas cette suite ! Procurez-vous ces timbres et articles de collection dès aujourd’hui. $ 208 Souvenir sheet Bloc-feuillet 403708145 16* Booklet of 8 stamps 64* Set of 4 booklets $ 4 Carnet de 8 timbres $ 16 Ensemble de 4 carnets 413708701 * Selection of individual booklet covers is random except when purchasing at participating post offi ces. Set of four booklets available by phone or online only. Le choix de la couverture individuelle des carnets est aléatoire, sauf si vous achetez les carnets 413708111 aux bureaux de poste participants. Vous pouvez vous procurer l’ensemble des quatre carnets, uniquement par téléphone ou en ligne. Offi cial First Day Cover and postcards also available. Sont également offerts un pli Premier Jour offi ciel ainsi que des cartes postales. Available at participating post offices or | Offert dans les bureaux de poste participants ou Canada / U.S. -

The Eye of the Painter and the Elements of Beauty

THE EYE OF THE PAINTER AND THE ELEMENTS OF BEAUTY Andrew Loomis THE VIKING PRESS • NEW YORK CONTENTS Prologue 13 I Seeing with the Painter's Eye 23 II "What Shall 1 Paint?" 35 III Unity 53 IV Simplicity and How to Achieve It 62 V Design 71 VI Proportion 84 VII Color 101 VIII Rhythm 108 IX Form 114 X Texture 121 XI Values of Light 126 XII Beauty of Subject 135 XIII Technique 138 ILLUSTRATIONS The Gulf Stream, Winslow Homer 15 Shed in the Swamp, Charles Burchfield 82 Movement, Sky and Sea, John Marin 16 Road with Cypresses. Vincent Van Gogh 92 Thinking Ahead, Yasuo Kuniyoshi 17 Marne at Nugent, Raoul Dufy 93 The Dull Fight, Francisco Goya 22 The Virgin with Saint Ines and Saint Tecla, Figure with Shawl, George Grosz 26 El Greco 95 Storm, Dean Fausett 33 The Lawyers, Honore Daumier 96 Fears and Pewter, Luigi Lucioni 37 The Wyndham Sisters, John Singer Sargent 97 Egg Dealer V, Stuart Davis 38 Upside Down Table and Mask, White Canadian Darn, No. 2, Yasuo Kuniyoshi 109 Georgia O'Keeffe 39 Expectation, Frederic Taubes 110 Figeon, Zoltan Sepeshy 42 Young Henry Ford, Norman Rockwell 1 17 Elephants, Russell Cowles 43 Venus of Cirene 118 Summer, John Koch 44 Music, Eugene Berman 119 Tile Hoof, Charles Burchfield 45 Paysage du Midi, Andre Derain 122 City Interior 1936, Charles Sheeler 46 Les Mouettes, Henri Matisse 123 The Outpost, William Thon 48 Fruit Dish Class and Newspaper, Juan Gris 124 Trouble Ahead, Margery Ryerson 49 The Pearl Necklace, Jan Vermeer 127 Quiet Evening, Hobson Pittman 50 Man with a Magnifying Glass. -

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home And

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 A Dissertation Presented by Shannon Jaleen Grove to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor oF Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University May 2014 Copyright by Shannon Jaleen Grove 2014 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Shannon Jaleen Grove We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Michele H. Bogart – Dissertation Advisor Professor, Department of Art Barbara E. Frank - Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, Department of Art Raiford Guins - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory Brian Rusted - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art / Department of Communication and Culture University of Calgary This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 by Shannon Jaleen Grove Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2014 This dissertation analyzes nationalisms in the work of Canadian magazine illustrators in Toronto and New York, 1880 to 1960. Using a continentalist approach—rather than the nationalist lens often employed by historians of Canadian art—I show the existence of an integrated, joint North American visual culture. Drawing from primary sources and biography, I document the social, political, corporate, and communication networks that illustrators traded in. I focus on two common visual tropes of the day—that of the pretty girl and that of wilderness imagery. -

The Secrets of Pangaea Paintings by James Waller

THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE LOFT GALLERY CLONAKILTY 5 JULY - 4 AUGUST 2018 ORIGIN AND MYTH The Secrets of Pangaea is essentially an exploration of the figure in the landscape and marks James Waller’s first foray into large-scale narrative oil painting, a journey inspired, in large part by the Norwegian master Odd Nerdrum, whom he stud- ied with in August and September 2017. The series revolves around two major compositions, The Children of Lir and The Secrets of Pangaea, and includes smaller works created whilst studying in Norway. The starting points for the major compositions are found in Greek and Irish mythology and include figures in states of both dramatic tension and Arcadian repose. The Secrets of Pangaea recalls the Tahitian paintings of Paul Gauguin, Waller’s first love as a young painter. The brooding sense of melancholy and langour, and the playing of music are symbiotic with Gauguin’s world. The approach to tone and colour, however, are very much informed by his immersion in Odd Nerdrum’s work and the Classical figurative approach. Several other pieces, such as Boy and Moon, Reverie and The Song of Pan- gaea are either derived from or studies for Secrets. Where Secrets only tangentially references Greek figures such as Pan and the Mino- taur, The Children of Lir explicitly references the famous Irish tale of the same name. It does not attempt to illustrate the story, but rather presents both bird and human form together, the human figures in a state of transformative tension, the swans in a state of lateral collapse (death?) and purposeful movement.