Thesis 23662729 Tripp F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

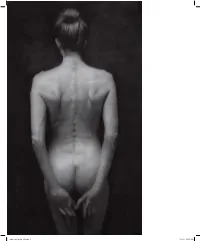

Zeller Int All 6P V2.Indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM the FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK

zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM THE FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK A CONTEMPORARY GUIDE TO FIGURE DRAWING, PAINTING, AND COMPOSITION ROBERT ZELLER FOREWORD BY PETER TRIPPI AFTERWORD BY KURT KAUPER MONACELLI STUDIO zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 2-3 11/4/16 12:23 PM Copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER and THE MONACELLI PRESS Illustrations copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER unless otherwise noted Text copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER Published in the United States by MONACELLI STUDIO, an imprint of THE MONACELLI PRESS All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zeller, Robert, 1966– author. Title: The figurative artist’s handbook : a contemporary guide to figure drawing, painting, and composition / Robert Zeller. Description: First edition. | New York, New York : Monacelli Studio, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007845 | ISBN 9781580934527 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Figurative drawing. | Figurative painting. | Human figure in art. | Composition (Art) | BISAC: ART / Techniques / Life Drawing. | ART / Techniques / Drawing. | ART / Subjects & Themes / Human Figure. Classification: LCC NC765 .Z43 2016 | DDC 743.4--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016007845 ISBN 978-1-58093-452-7 Printed in China Design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover illustrations by ROBERT ZELLER Illustration credits appear on page 300. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is dedicated to my daughter, Emalyn. First Edition This book was inspired by Kenneth Clark's The Nude and Andrew Loomis's Figure Drawing for All It's Worth. MONACELLI STUDIO This book would not have been possible without the help of some important peo- THE MONACELLI PRESS 236 West 27th Street ple. -

EES PEKE MF-$3.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage

DOCUMENT RESUME ED'124 95 CS 202 789 English 591, 592, and 593--Advante Program: Images of - Man. INSTTUTIYN Jeffersrin County Board of EdLication, Louisvilke, Ky. PUB DATE 73 A NOTE . 117p. EES PEKE MF-$3.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DEJCEIPT9 Ameiican Literature; Composition Skills(Literary): *English Instruction; *Enqlish1LiteraturExpository Writing; *Gifted; Grade 12;.4q,ancipage Arts; *Lit,erature Appreciation; Secondary ducaltion 0/RSTFAc: For those students whq qualify, the Ad'ance Program. offers an opportunity to follow a stim atingitcurriculum desi4ned for the academically talented. The purposes f the course outlined in this guide for twelfth grade English ate- to brill4 the previous three years' studies in dvance Frogram 1nglish to -a-Meaningful c lmination; to c vide a chall ing, practical, college-level arse of study _hat includes t e traditionaltwelfth grade 'experiences in English?literat re; to expandhese experiences to /include represettatiyre liter-cure that offers a world view of the universality cf human exper ence; and to prepafe studentsadequaely' for advanced placement in co lege, The introductory unit onthe Fis'Iory of the English langue reinfrorces ninth and tenth grade linguistic studies and provide experieliceA'designed to bring the, stucents to a realization of t dynamic character of their /1 nguage--from Beowulf and Chau r to. Eliot and Shaw. The units 1 include exercises in expositor writing in correlation with the literature studies So that the studentcan discover their basic deficiencies and strengthen their skills. (JM) a. ******************************* Documents acquired by FR; includQ many informal anpubliShed *- * materials not avai ble from o her sources. ERIC makes every effort * . -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

Adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents

.....••_•____________•. • adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents Ordering Information 2 Arabic * Middle Eastern 51 Order Blank 3 Jewish 52 About Ladyslipper 4 Alternative 53 Donor Discount Club * Musical Month Club 5 Rock * Pop 56 Readers' Comments 6 Folk * Traditional 58 Mailing List Info * Be A Slipper Supporter! 7 Country 65 Holiday 8 R&B * Rap * Dance 67 Calendars * Cards 11 Gospel 67 Classical 12 Jazz 68 Drumming * Percussion 14 Blues 69 Women's Spirituality * New Age 15 Spoken 70 Native American 26 Babyslipper Catalog 71 Women's Music * Feminist Music 27 "Mehn's Music" 73 Comedy 38 Videos 77 African Heritage 39 T-Shirts * Grab-Bags 82 Celtic * British Isles 41 Songbooks * Sheet Music 83 European 46 Books * Posters 84 Latin American . 47 Gift Order Blank * Gift Certificates 85 African 49 Free Gifts * Ladyslipper's Top 40 86 Asian * Pacific 50 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat'11-5) Ordering Information INFORMATION: 919-683-1570 (same as above) FAX: 919-682-5601 (24 hours'7 days a week) PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available. LP = record, CS = cassette, CD = com schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives pact disc. Some recordings are available only on LP Ladyslipper, Inc. -

The Secrets of Pangaea Paintings by James Waller

THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE LOFT GALLERY CLONAKILTY 5 JULY - 4 AUGUST 2018 ORIGIN AND MYTH The Secrets of Pangaea is essentially an exploration of the figure in the landscape and marks James Waller’s first foray into large-scale narrative oil painting, a journey inspired, in large part by the Norwegian master Odd Nerdrum, whom he stud- ied with in August and September 2017. The series revolves around two major compositions, The Children of Lir and The Secrets of Pangaea, and includes smaller works created whilst studying in Norway. The starting points for the major compositions are found in Greek and Irish mythology and include figures in states of both dramatic tension and Arcadian repose. The Secrets of Pangaea recalls the Tahitian paintings of Paul Gauguin, Waller’s first love as a young painter. The brooding sense of melancholy and langour, and the playing of music are symbiotic with Gauguin’s world. The approach to tone and colour, however, are very much informed by his immersion in Odd Nerdrum’s work and the Classical figurative approach. Several other pieces, such as Boy and Moon, Reverie and The Song of Pan- gaea are either derived from or studies for Secrets. Where Secrets only tangentially references Greek figures such as Pan and the Mino- taur, The Children of Lir explicitly references the famous Irish tale of the same name. It does not attempt to illustrate the story, but rather presents both bird and human form together, the human figures in a state of transformative tension, the swans in a state of lateral collapse (death?) and purposeful movement. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Pictures Every Child Should Know, by Dolores Bacon

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pictures Every Child Should Know, by Dolores Bacon Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Pictures Every Child Should Know Author: Dolores Bacon Release Date: November, 2004 [EBook #6932] [This file was first posted on February 12, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: iso-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, PICTURES EVERY CHILD SHOULD KNOW *** Arno Peters, Branko Collin, Tiffany Vergon, Charles Aldarondo, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team PICTURES EVERY CHILD SHOULD KNOW A SELECTION OF THE WORLD'S ART MASTERPIECES FOR YOUNG PEOPLE BY DOLORES BACON Illustrated from Great Paintings ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Besides making acknowledgments to the many authoritative writers upon artists and pictures, here quoted, thanks are due to such excellent compilers of books on art subjects as Sadakichi Hartmann, Muther, C. -

Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2007 And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Perry Walter, "And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2151. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2151 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art and Design East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts by Perry Johnson December 2006 M. Wayne Dyer, Chair Ralph Slatton David Dixon Keywords: painting, alienation, conformity, machine, figurative ABSTRACT And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture by Perry Johnson Man has created vast and powerful systems. These systems and their associated protocols, dogmas, and conventions tend to limit rather than liberate. Evaluation based on homogeneity threatens the devaluation of our humanity. This paper and the artwork it supports examine contemporary culture and its failings in the stewardship of the humanist ideal. -

NORMAN ROCKWELL (After) - Sculptures

NORMAN ROCKWELL (After) - Sculptures Authorized Estate sculptures created after Rockwell’s original paintings. Born Norman Percevel Rockwell in New York City on February 3, 1894, Norman Rockwell knew at the age of 14 that he wanted to be an artist, and began taking classes at The New School of Art. By the age of 16, Rockwell was so intent on pursuing his passion that he dropped out of high school and enrolled at the National Academy of Design. A prolific and popular illustrator who produced 323 designs for covers of the Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell created views of American life that were often sentimental, sometimes gently satirical, and occasionally rather pointed in social commentary in a detailed style ideal for mass reproduction and consumption. Rockwell’s success stemmed to a large degree from his careful appreciation for everyday American scenes, the warmth of small-town life in particular. Often what he depicted was treated with a certain simple charm and sense of humor. “Maybe as I grew up and found the world wasn’t the perfect place I had thought it to be, I unconsciously decided that if it wasn’t an ideal world, it should be, and so painted only the ideal aspects of it,” he once said. In 1977— one year before his death—Rockwell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford. In his speech Ford said, “Artist, illustrator and author, Norman Rockwell has portrayed the American scene with unrivaled freshness and clarity. Insight, optimism and good humor are the hallmarks of his artistic style. -

Title Author Call Number

Art Title Author Call Number Nineteenth century French art : from Romanticism to Impressionism, post- Impressionism and Art Nouveau / Henri Loyrette, general editor ; SeLbastien Allard and Laurence des Cars ; [translated from the French by David Radzinowicz]. Allard, SeLbastien. 709.44034 NIN Brodskaio8 ao8!, N. V. Symbolism / [text: Nathalia BrodskaiLa ; translation Tatyana Shlyak and Rebecca (NatalJ9io8 ao8! Brimacombe]. Valentinovna) 759.057 Essays in migratory aesthetics : cultural practices between migration and art-making / BH301.C92 E87 editors, Sam Durrant, Catherine M. Lord. 2007 China : empire and civilization / edited by Edward L. Shaughnessy. DS706 .C4945 2005 Celts : history and treasures of an ancient civilization / [texts, Daniele Vitali ; translation, Corinne Colette]. Vitali, Daniele. N5925 .V5813 2007 Facts and artefacts : art in the Islamic world : festschrift for Jens KroLger on his 65th birthday / edited by Annette Hagedorn, Avinoam Shalem. N6260 .F27 2007 Renaissance art / [Victoria Charles ; translation, Marlena Metcalf]. Charles, Victoria. N6370 .C4318 2007 N6512.5.P6 M66 Pop art portraits / Paul Moorhouse ; with an essay by Dominic Sandbrook. Moorhouse, Paul. 2007 Complete catalogue of known and documented work by William Merritt Chase (1849- N6537.C464 A4 1916) / Ronald G. Pisano / completed by D. Frederick Baker. Pisano, Ronald G. 2006 Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe Museum collections / Barbara Buhler Lynes. 1942- N6537.O39 A4 2007 Lucian Freud / Sebastian Smee. Smee, Sebastian. N6797.F77 A4 2007 N6921.S6 R358 Renaissance Siena : art for a city / Luke Syson ... [et al.]. 2007 Differencing the canon : feminist desire and the writing of art's histories / Griselda Pollock. Pollock, Griselda. N72.F45 P63 1999 Visual shock : a history of art controversies in American culture / Michael Kammen. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun