The Artist Interview: an Elusive History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharing Mindfulness: a Moral Practice for Artist Teachers. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 18(26)

International Journal of Education & the Arts Editors Terry Barrett Peter Webster Ohio State University University of Southern California Eeva Anttila Brad Haseman University of the Arts Helsinki Queensland University of Technology http://www.ijea.org/ ISSN: 1529-8094 Volume 18 Number 26 June 25, 2017 Sharing Mindfulness: A Moral Practice for Artist Teachers Rebecca Heaton Northampton University, United Kingdom Alice Crumpler Northampton University, United Kingdom Citation: Heaton, R., & Crumpler, A. (2017). Sharing mindfulness: A moral practice for artist teachers. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 18(26). Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v18n26/. Abstract By exploring changemaker principles as a component of social justice art education this research informed article exemplifies how moral consciousness and responsibility can be developed when training artist teachers. It embeds changemaker philosophy in the higher education art curriculum and demonstrates how this can create ruptures and ripples into educational pedagogy at the school level. A sociocultural qualitative methodology, that employs questionnaires, the visual and a focus group as methods, is used to reveal three lenses on student perceptions of the changemaker principle. The dissemination of these perceptions and sharing of active art experiences communicate how engagement with the concept of changemaker in art education can deepen the cognitive growth of learners, whilst facilitating an understanding of and involvement in interculturality. IJEA Vol. 18 No. 26 - http://www.ijea.org/v18n26/ 2 Introduction At Northampton University in the United Kingdom an awareness of positive social impact underpins learning. Our students are changemakers, individuals who identify a need or problem in a society that they can address through progressive, moral or sustainable actions. -

American Visionary: John F. Kennedy's Life and Times

American Visionary: John F. Kennedy’s Life and Times Organized by Wiener Schiller Productions in collaboration with the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Curated by Lawrence Schiller Project Coordinator: Susan Bloom All images are 11 x 14 inches All frames are 17 x 20 inches 1.1 The Making of JFK John “Jack” Fitzgerald Kennedy at Nantasket Beach, Massachusetts, circa 1918. Photographer unknown (Corbis/Getty Images) The still-growing Kennedy family spent summers in Hull, Massachusetts on the Boston Harbor up to the mid-1920s, before establishing the family compound in Hyannis Port. 1.2 The Making of JFK A young Jack in the ocean, his father nearby, early 1920s. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Library Foundation) Kennedy’s young life was punctuated with bouts of illness, but he was seen by his teachers as a tenacious boy who played hard. He developed a great love of reading early, with a special interest in British and European history. 1.3 The Making of JFK Joseph Kennedy with sons Jack (left) and Joseph Patrick Jr., Brookline, Massachusetts, 1919. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Library Foundation) In 1919 Joe Kennedy began his career as stockbroker, following a position as bank president which he assumed in 1913 at age twenty-five. By 1935, his wealth had grown to $180 million; the equivalent to just over $3 billion today. Page 1 Updated 3/7/17 1.4 The Making of JFK The Kennedy children, June, 1926. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum) Left to right: Joe Jr., Jack, Rose Marie, Kathleen, and Eunice, taken the year Joe Kennedy Sr. -

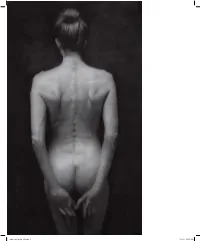

Zeller Int All 6P V2.Indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM the FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK

zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM THE FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK A CONTEMPORARY GUIDE TO FIGURE DRAWING, PAINTING, AND COMPOSITION ROBERT ZELLER FOREWORD BY PETER TRIPPI AFTERWORD BY KURT KAUPER MONACELLI STUDIO zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 2-3 11/4/16 12:23 PM Copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER and THE MONACELLI PRESS Illustrations copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER unless otherwise noted Text copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER Published in the United States by MONACELLI STUDIO, an imprint of THE MONACELLI PRESS All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zeller, Robert, 1966– author. Title: The figurative artist’s handbook : a contemporary guide to figure drawing, painting, and composition / Robert Zeller. Description: First edition. | New York, New York : Monacelli Studio, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007845 | ISBN 9781580934527 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Figurative drawing. | Figurative painting. | Human figure in art. | Composition (Art) | BISAC: ART / Techniques / Life Drawing. | ART / Techniques / Drawing. | ART / Subjects & Themes / Human Figure. Classification: LCC NC765 .Z43 2016 | DDC 743.4--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016007845 ISBN 978-1-58093-452-7 Printed in China Design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover illustrations by ROBERT ZELLER Illustration credits appear on page 300. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is dedicated to my daughter, Emalyn. First Edition This book was inspired by Kenneth Clark's The Nude and Andrew Loomis's Figure Drawing for All It's Worth. MONACELLI STUDIO This book would not have been possible without the help of some important peo- THE MONACELLI PRESS 236 West 27th Street ple. -

Environmental Regulation of Rural Properties in Matopiba

PRIMER ON ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATION OF RURAL PROPERTIES IN MATOPIBA 3rd EDITION REVISED AND AMPLIFIED Environmental Regularization Support Center 1 PUBLISHERS AND EDITORS REALIZATION Association of Farmers and Irrigators of Bahia - AIBA SUPPORT Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries - Abiove AUTHORSHIP Dra. Alessandra Terezinha Chaves Cotrim Reis, Environmental Director TECHNICAL TEAM Adolfo Andrade Daniel Moreira Eneas Porto Glauciana Araújo Jonathas Alves Cruz Raquel Paiva REVISION Ana Brinquedo Catiane Magalhães Bernardo Pires COLLABORATION Alessia Oliveira Bernardo Pires Helmuth Kieckhöfer Natalie Ribeiro TRANSLATION Joshua Martin Daniel Manoel Santana Rebouças PHOTOGRAPHY AIBA’s collection Rui Rezende (cover photo) GRAPHIC DESIGN AND EDITING Marca Studio ILLUSTRATIONS Fábio Ferreira 2 Environmental Regularization Support Center Environmental Regularization Support Center 3 ÍNDICE 07. PRESENTATION 09. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ABOUT ENVIRONMENTAL REGULARIZATION 16. CONSOLIDATED RURAL AREAS 18. LEGAL RESERVE 20. LEGAL RESERVE COMPENSATION 23. RECOVERY OF LEGAL RESERVE 26. AREAS OF PERMANENT PRESERVATION (APP) 52. AREAS OF RESTRICTED USE 54. REGULARIZATION OF RURAL PROPERTIES 56. FISCAL MODULE 57. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS 58. GLOSSARY 61. LEGISLATION CONSULTED 4 Environmental Regularization Support Center Environmental Regularization Support Center 5 PRESENTATION The Primer on Environmental Regulation of Rural Properties in Bahia, prepared in 2015 by the Association of Farmers and Irrigators of Bahia (AIBA), has just published a new -

Drones and Surveillance Cultures in a Global World.” Digital Studies/Le Champ Numérique 9(1): 18, Pp

Research How to Cite: Muthyala, John. 2019. “Drones and Surveillance Cultures in a Global World.” Digital Studies/Le champ numérique 9(1): 18, pp. 1–51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.332 Published: 27 September 2019 Peer Review: This is a peer-reviewed article in Digital Studies/Le champ numérique, a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Digital Studies/Le champ numérique is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. Muthyala, John. 2019. “Drones and Surveillance Cultures in a Global World.” Digital Studies/Le champ numérique 9(1): 18, pp. 1–51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.332 RESEARCH Drones and Surveillance Cultures in a Global World John Muthyala University of Southern Maine, US [email protected] Digital technologies are essential to establishing new forms of dominance through drones and surveillance systems; these forms have significant effects on individuality, privacy, democracy, and American foreign policy; and popular culture registers how the uses of drone technologies for aesthetic, educational, and governmental purposes raise questions about the exercise of individual, governmental, and social power. By extending computational methodologies in the digital humanities like macroanalysis and distant reading in the context of drones and surveillance, this article demonstrates how drone technologies alter established notions of war and peace, guilt and innocence, privacy and the common good; in doing so, the paper connects postcolonial studies to the digital humanities. -

Dépliant De L'exposition Dali 2012

DALÍ 21 NOVEMBER 2012 - 25 MARCH 2013 Over thirty years after the major experiences on our relationship with retrospective exhibition dedicated to space, matter and reality. the painter in the early days of the The imaginative, curious and prodigal Centre Pompidou, Dalí – the artist artist used himself as a subject of who proclaimed himself as “divine” study, notably under the prism of and a “genius” – is once again in the Freudian psychoanalysis. He built his media spotlight. Dalí is both a key own character and set the scene for figures in the history of modern art his own performance. His actions in and one of the most popular. He is the public sphere, whether calculated also one of the most controversial or improvised, now reveal him as one artists, often denounced for his of the precursors of showmanship. showing-off and his provocative political positions. The Dalí exhibition brings together over 120 paintings, as well as Creator of an unprecedented drawings, objects, sketches, films and dreamlike universe, Dalí is mainly archival documents. It is laid out in known for his surrealist paintings of chronological-thematic sections: the the 1930s and for his television dialogue between the artist’s eye and appearances. The inventor of the brain and those of the spectator; Dalí, famous “paranoiac-critical”w method a pioneer in showmanship, creator of also echoed his era’s scientific ephemeral works and media discoveries, which impelled him to manipulator; the questioning of the constantly push back the limits of his artist’s figure in the face of tradition. www.centrepompidou.fr ULTRA-LOCAL AND UNIVERSAL showing like in the Écorchés collection. -

The Secrets of Pangaea Paintings by James Waller

THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE SECRETS OF PANGAEA PAINTINGS BY JAMES WALLER THE LOFT GALLERY CLONAKILTY 5 JULY - 4 AUGUST 2018 ORIGIN AND MYTH The Secrets of Pangaea is essentially an exploration of the figure in the landscape and marks James Waller’s first foray into large-scale narrative oil painting, a journey inspired, in large part by the Norwegian master Odd Nerdrum, whom he stud- ied with in August and September 2017. The series revolves around two major compositions, The Children of Lir and The Secrets of Pangaea, and includes smaller works created whilst studying in Norway. The starting points for the major compositions are found in Greek and Irish mythology and include figures in states of both dramatic tension and Arcadian repose. The Secrets of Pangaea recalls the Tahitian paintings of Paul Gauguin, Waller’s first love as a young painter. The brooding sense of melancholy and langour, and the playing of music are symbiotic with Gauguin’s world. The approach to tone and colour, however, are very much informed by his immersion in Odd Nerdrum’s work and the Classical figurative approach. Several other pieces, such as Boy and Moon, Reverie and The Song of Pan- gaea are either derived from or studies for Secrets. Where Secrets only tangentially references Greek figures such as Pan and the Mino- taur, The Children of Lir explicitly references the famous Irish tale of the same name. It does not attempt to illustrate the story, but rather presents both bird and human form together, the human figures in a state of transformative tension, the swans in a state of lateral collapse (death?) and purposeful movement. -

Philippe Halsman Étonnez-Moi ! 20/10/2015 – 24/01/2016

PHiLiPPe HALsMAN ÉToNNeZ-MOI ! 20/10/2015 – 24/01/2016 dossier DOCUMeNTAIRE DOSSIER doCUMeNTAIRE CoNTACTs Mode d’eMPLoi Conçu par le service éducatif, en collaboration Pauline Boucharlat avec l’ensemble du Jeu de Paume, ce dossier propose chargée des publics scolaires et des partenariats aux enseignants et aux équipes éducatives des éléments 01 47 03 04 95 / [email protected] de documentation, d’analyse et de réflexion. Marie-Louise Ouahioune Il se compose de trois parties : réservation des visites et des activités Découvrir l’exposition offre une première approche 01 47 03 12 41 / [email protected] du projet et du parcours de l’exposition, des artistes et des œuvres, ainsi que des repères chronologiques Sabine Thiriot et iconographiques. responsable du service éducatif [email protected] Approfondir l’exposition développe plusieurs axes thématiques autour du statut des images et de l’histoire conférenciers et formateurs des arts visuels, ainsi que des orientations bibliographiques Ève Lepaon et des ressources en ligne. 01 47 03 12 42 / [email protected] Benjamin Bardinet Pistes de travail comporte des propositions et des ressources 01 47 03 12 42 / [email protected] pédagogiques élaborées avec les professeurs-relais des académies de Créteil et de Paris au Jeu de Paume. professeur-relais Céline Lourd, académie de Paris Disponible sur demande, le dossier documentaire [email protected] est également téléchargeable depuis le site Internet Cédric Montel, académie de Créteil du Jeu de Paume (document PDF avec hyperliens actifs). [email protected] La RATP invite PHILIPPE HALSMAN Partenaire du Jeu de Paume, la RATP accompagne la rétrospective photographique « Philippe Halsman. -

Christie's New York to Offer Three Exceptional

PRESS RELEASE | NEW YORK | 17 M A R C H 2 0 1 4 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CHRISTIE’S NEW YORK TO OFFER THREE EXCEPTIONAL PHOTOGRAPHS SALES IN APRIL April 3 – The Range of Light: Photographs by Ansel Adams April 3 – Photographs March 28-April 10 – April in Paris, an Online Only Sale LEFT: Edouard Boubat, Lella, Bretagne, France, 1948, gelatin silver print, Estimate: $6,000-8,000 CENTER: Ansel Adams, Winter Sunrise, Sierra Nevada from Lone Pine, California, 1941, gelatin silver mural print, printed 1961, Estimate; $300,000-500,000 RIGHT: Philippe Halsman, Marilyn Monroe, 1952, gelatin silver print, Estimate: $70,000-90,000 New York – Christie’s is pleased to announce three Photographs sales to be offered in April –The Range of Light: Photographs by Ansel Adams, a live auction on April 3 dedicated to works by the artist; Photographs, a live auction (also on April 3), which will include a wide range of artists, from the early 20th century through today; and April in Paris, an online-only sale that will be open for bidding from March 28-April 10. THE RANGE OF LIGHT: PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANSEL ADAMS APRIL 3 On April 3, Christie’s will present The Range of Light: Photographs by Ansel Adams, an auction dedicated solely to the work of this preeminent American artist. Featuring 25 lots that will appeal to new and seasoned buyers alike, the sale presents a wide variety of his best known images, including several rare, large-format ‘mural’ prints. This sale celebrates Adams’ colossal talent and his meticulous creative process, through which he was able to produce technically flawless prints from his carefully composed negatives. -

The Prints of Allan D'arcangelo

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas May – June 2015 Volume 5, Number 1 Fourth Anniversary • Allan D’Arcangelo • Marcus Rees Roberts • Jane Hyslop • Equestrian Prints of Wenceslaus Hollar In Memory of Michael Miller • Lucy Skaer • In Print / Imprint in the Bronx • Prix de Print • Directory 2015 • News MARLONMARLONMARLON WOBST WOBSTWOBST TGIFTGIF TGIF fromfrom a series a series of fourof four new new lithographs lithographs keystonekeystone editions editionsfinefine art printmakingart printmaking from a series of four new lithographs berlin,keystoneberlin, germany germany +49 editions +49(0)30 (0)30 8561 8561 2736 2736fine art printmaking Edition:Edition: 20 20 [email protected],[email protected] germany +49 (0)30 www.keystone-editions.net 8561 www.keystone-editions.net 2736 6-run6-run lithographs, lithographs, 17.75” 17.75”Edition: x 13” x 13”20 [email protected] www.keystone-editions.net 6-run lithographs, 17.75” x 13” May – June 2015 In This Issue Volume 5, Number 1 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Random Houses Associate Publisher Linda Konheim Kramer 3 Julie Bernatz The Prints of Allan D’Arcangelo Managing Editor Ben Thomas 7 Dana Johnson The Early Prints of Marcus Rees Roberts News Editor Isabella Kendrick Ruth Pelzer-Montada 12 Knowing One’s Place: Manuscript Editor Jane Hyslop’s Entangled Gardens Prudence Crowther Simon Turner 17 Online Columnist The Equestrian Portrait Prints Sarah Kirk Hanley of Wenceslaus Hollar Design Director Lenore Metrick-Chen 23 Skip Langer The Third Way: An Interview with Michael Miller Editor-at-Large Catherine Bindman Prix de Print, No. -

Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2007 And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture. Perry Walter Johnson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Perry Walter, "And This, Our Measure: Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2151. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2151 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art and Design East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts by Perry Johnson December 2006 M. Wayne Dyer, Chair Ralph Slatton David Dixon Keywords: painting, alienation, conformity, machine, figurative ABSTRACT And This, Our Measure Figurative Realism and Workaday Culture by Perry Johnson Man has created vast and powerful systems. These systems and their associated protocols, dogmas, and conventions tend to limit rather than liberate. Evaluation based on homogeneity threatens the devaluation of our humanity. This paper and the artwork it supports examine contemporary culture and its failings in the stewardship of the humanist ideal. -

Title Author Call Number

Art Title Author Call Number Nineteenth century French art : from Romanticism to Impressionism, post- Impressionism and Art Nouveau / Henri Loyrette, general editor ; SeLbastien Allard and Laurence des Cars ; [translated from the French by David Radzinowicz]. Allard, SeLbastien. 709.44034 NIN Brodskaio8 ao8!, N. V. Symbolism / [text: Nathalia BrodskaiLa ; translation Tatyana Shlyak and Rebecca (NatalJ9io8 ao8! Brimacombe]. Valentinovna) 759.057 Essays in migratory aesthetics : cultural practices between migration and art-making / BH301.C92 E87 editors, Sam Durrant, Catherine M. Lord. 2007 China : empire and civilization / edited by Edward L. Shaughnessy. DS706 .C4945 2005 Celts : history and treasures of an ancient civilization / [texts, Daniele Vitali ; translation, Corinne Colette]. Vitali, Daniele. N5925 .V5813 2007 Facts and artefacts : art in the Islamic world : festschrift for Jens KroLger on his 65th birthday / edited by Annette Hagedorn, Avinoam Shalem. N6260 .F27 2007 Renaissance art / [Victoria Charles ; translation, Marlena Metcalf]. Charles, Victoria. N6370 .C4318 2007 N6512.5.P6 M66 Pop art portraits / Paul Moorhouse ; with an essay by Dominic Sandbrook. Moorhouse, Paul. 2007 Complete catalogue of known and documented work by William Merritt Chase (1849- N6537.C464 A4 1916) / Ronald G. Pisano / completed by D. Frederick Baker. Pisano, Ronald G. 2006 Lynes, Barbara Buhler, Georgia O'Keeffe Museum collections / Barbara Buhler Lynes. 1942- N6537.O39 A4 2007 Lucian Freud / Sebastian Smee. Smee, Sebastian. N6797.F77 A4 2007 N6921.S6 R358 Renaissance Siena : art for a city / Luke Syson ... [et al.]. 2007 Differencing the canon : feminist desire and the writing of art's histories / Griselda Pollock. Pollock, Griselda. N72.F45 P63 1999 Visual shock : a history of art controversies in American culture / Michael Kammen.