Environmental Law Developments in Nuclear Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..196 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 144 Ï NUMBER 025 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 40th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, March 6, 2009 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1393 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, March 6, 2009 The House met at 10 a.m. Some hon. members: Yes. The Speaker: The House has heard the terms of the motion. Is it the pleasure of the House to adopt the motion? Prayers Some hon. members: Agreed. (Motion agreed to) GOVERNMENT ORDERS Mr. Mark Warawa (Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of the Environment, CPC) moved that Bill C-17, An Act to Ï (1005) recognize Beechwood Cemetery as the national cemetery of Canada, [English] be read the second time and referred to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development. NATIONAL CEMETERY OF CANADA ACT He said: Mr. Speaker, I would like to begin by seeking unanimous Hon. Jay Hill (Leader of the Government in the House of consent to share my time. Commons, CPC): Mr. Speaker, momentarily, I will be proposing a motion by unanimous consent to expedite passage through the The Speaker: Does the hon. member have unanimous consent to House of an important new bill, An Act to recognize Beechwood share his time? Cemetery as the national cemetery of Canada. However, before I Some hon. members: Agreed. propose my motion, which has been agreed to in advance by all parties, I would like to take a quick moment to thank my colleagues Mr. -

It June 17/04 Copy

Strait of Georgia VOTE! Monday Every Second Thursday & Online ‘24/7’ at islandtides.com June 28th Canadian Publications Mail Product Volume 16 Number 11 Your Coastal Community Newspaper June 17–June 30, 2004 Sales Agreement Nº 40020421 Tide tables 2 Saturna notes 3 Letters 4 What’s on? 5 Advance poll 7 Bulletin board 11 Closely watched votes: Saanich–Gulf Islands race may be critical The electoral battle for the federal parliamentary seat in the Saanich-Gulf Islands riding has drawn national attention. It’s not just that the race has attracted four strong candidates from the Conservative, Liberal, NDP and Photo: Brian Haller Green parties. It’s that the riding has the Haying at Deacon Vale Farm, one of Mayne Island’s fourteen farms. Mayne’s Farmers Market begins in July. best chance in Canada to actually elect a Green Party member. The Green Party is running candidates in all 308 federal ridings in Elections, then and now ~ Opinion by Christa Grace-Warrick & Patrick Brown this election, the first time it has done this. Nationally, polls have put the Green t has been said that generals are always fighting the previous war. It in debate and more free votes. If this is the case, the other parties will vote at a couple of percentage points. might also be said that politicians are always fighting the last election, eventually have to do the same. The polls (as we write) indicate the possibility But the Greens have plenty of room to Iand that the media are always reporting the last election. -

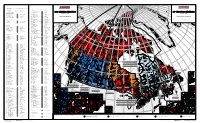

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

Core 1..132 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 6.50.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 137 Ï NUMBER 167 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, April 12, 2002 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 10343 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, April 12, 2002 The House met at 10 a.m. fish products, to sell or otherwise dispose of these products, and to make deficiency payments to producers. The intent of the act was to Prayers protect fishermen against sharp declines in prices and consequent loss of income due to causes beyond the control of fishermen or the fishing industry. GOVERNMENT ORDERS The board has not undertaken any significant price support Ï (1000) activities since 1982 except for the purchase of fish as food aid for [English] distribution by CIDA. AN ACT TO AMEND CERTAIN ACTS AND INSTRUMENTS AND TO REPEAL THE FISHERIES PRICES SUPPORT ACT Bill C-43 can be considered a hybrid of the Miscellaneous Statute Law Amendment Act. Bill C-43 contains a number of provisions The House resumed from December 7 consideration of the omitted from the draft of the Miscellaneous Statute Law Amendment motion that Bill C-43, an act to amend certain Acts and instruments Act, MSLA, Bill C-40. The miscellaneous statute law amendment and to repeal the Fisheries Prices Support Act, be read the third time program was initiated in 1975 to allow for minor, non-controversial and passed. amendments to federal statutes in an omnibus bill. -

Unplugging the Dirty Energy Economy / Ii

Polaris Institute, June 2015 The Polaris Institute is a public interest research organization based in Canada. Since 1997 Polaris has been dedicated to developing tools and strategies to take action on major public policy issues, including the corporate power that lies behind public policy making, on issues of energy security, water rights, climate change, green economy and global trade. Acknowledgements This Profile was researched and written by Mehreen Amani Khalfan, with additional research from Richard Girard, Daniel Cayley-Daoust, Erin Callary, Alexandra Bly and Brianna Aird. Special thanks to Heather Milton-Lightening and Clayton Thomas-Muller for their contributions. Cover design by Spencer Mann. This project was made possible through generous support from the European Climate Fund Polaris Institute 180 Metcalfe Street, Suite 500 Ottawa, ON K2P 1P5 Phone: 613-237-1717 Fax: 613-237-3359 Email: [email protected] www.polarisinstitute.org i / Polaris Institute Table of Contents SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1 - ORGANIZATIONAL PROFILE ............................................................................................................... 6 1.1 TRANSCANADA’S BUSINESS STRUCTURE AND OPERATIONS .............................................................................................. -

Bioenergy Policy and Regulation in Canada – November 2009

Timeline Bioenergy Policy and Regulation in Canada Last Update: November 2009 Principal Researcher: Alin Charrière Master’s Student, School of Public Policy and Administration Series Editor: Marc Saner, Director of Research, Regulatory Governance Initiative Explanatory Note This timeline outlines important events related to bioenergy policy and regulation in Canada with an emphasis on biofuels and developments since 2000. For the purposes of this timeline, Bioenergy refers to various forms of renewable energy produced from biomass, such as biofuels, biopower and bioheat. The research team has made an effort to highlight events relevant to the forestry sector. For background purposes, the research team has also chosen to include broader developments in energy policy as well as significant events outside of Canada where deemed appropriate. Please help us keep this timeline accurate and up-to-date by providing comments to [email protected]. Acknowledgments The following individuals contributed to the development of this timeline: Jeffery Cottes, Holly Mitchell, Dr. Jennifer Pelley, Prof. Myron Smith and Prof. David Miller. The Regulatory Governance Initiative also gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Forest Products Association of Canada (FPAC) and the Canada School of Public Service, without which this work would not have been possible. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non-commercial – No Derivatives License. To view this license, visit (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/). For re-use or distribution, please include this copyright notice. © 2009 Regulatory Governance Initiative, Carleton University Timeline – Bioenergy Policy and Regulation in Canada Event Who When Description Relates To Early vehicles use a Various Early 1900s Early vehicles are powered by a diversity of fuels such as ethanol, diesel, History of wide variety of biofuels butanol, peanut oil, fuels obtained through pyrolysis or gasification, etc. -

Friday, March 16, 2001

CANADA VOLUME 137 S NUMBER 030 S 1st SESSION S 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, March 16, 2001 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1755 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, March 16, 2001 The House met at 10 a.m. an environment in which wildlife can prosper, live and provide enjoyment for each of us. _______________ It is important to recognize our support of the intent of this Prayers particular bill. I want to be sure that everyone out there recognizes that the Canadian Alliance, myself in particular, and its constitu- _______________ ents support the protection of wildlife. What we need to recognize here, though, is how the bill will be GOVERNMENT ORDERS handled. I wish to refer to certain provisions in the bill. The first provision of the bill is the selection of the list of species and endangered wildlife that will be registered and protected by the D (1005) bill. [English] Clause 14 deals with this particular part of the activities, so I will SPECIES AT RISK ACT refer, then, to clause 14, which suggests that a committee be established. It is called the COSEWIC committee and many of the The House resumed from February 28 consideration of the listeners will wonder what in the world we are talking about. That motion that Bill C-5, an act respecting the protection of wildlife is an acronym for a long title, Committee on the Status of species at risk in Canada, be read the second time and referred to a Endangered Wildlife in Canada. -

Maintaining Party Unity: Analyzing the Conservative Party of Canada's

Maintaining Party Unity: Analyzing the Conservative Party of Canada’s Integration of the Progressive Conservative and Canadian Alliance parties by Matthew Thompson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2017, Matthew Thompson Federal conservative parties in Canada have long been plagued by several persistent cleavages and internal conflict. This conflict has hindered the party electorally and contributed to a splintering of right-wing votes between competing right-wing parties in the 1990s. The Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) formed from a merger of the Progressive Conservative (PC) party and the Canadian Alliance in 2003. This analysis explores how the new party was able to maintain unity and prevent the long-standing cleavages from disrupting the party. The comparative literature on party factions is utilized to guide the analysis as the new party contained faction like elements. Policy issues and personnel/patronage distribution are stressed as significant considerations by the comparative literature as well literature on the PCs internal fighting. The analysis thus focuses on how the CPC approached these areas to understand how the party maintained unity. For policy, the campaign platforms, Question Period performance and government sponsored bills of the CPC are examined followed by an analysis of their first four policy conventions. With regards to personnel and patronage, Governor in Council and Senate appointments are analyzed, followed by the new party’s candidate nomination process and Stephen Harper’s appointments to cabinet. The findings reveal a careful and concentrated effort by party leadership, particularly Harper, at managing both areas to ensure that members from each of the predecessor parties were motivated to remain in the new party. -

The Puzzle of Independence and Parliamentary Democracy in the Common Law World: a Canadian Perspective

The Puzzle of Independence and Parliamentary Democracy in the Common Law World: A Canadian Perspective by Lorne Sossin1 This chapter explores the relationship between partisanship and independence in administrative law in Canada and the common law world. Partisanship is endemic to Parliamentary democracy. The fusion of legislative and executive roles means that the leadership of the executive branch of government (i.e. the Prime Minister and Cabinet) is selected from the political party that leads the legislative branch of government through the confidence of Parliament. At the same time, as the Crown, the executive leadership cannot exercise public powers in ways intended to benefit one party or one partisan perspective on public policy matters. Partisanship thus drives the process that produces the executive branch, but has no legitimate role as a goal or motivation in the exercise of public authority. Consequently, it should come as no surprise that a key tension in the development of administrative law in Canada, and elsewhere in the common law world, is how to ensure executive decision-making is sufficiently independent –that is, not unduly influenced or undermined by partisan considerations. Independence can be eroded by partisanship from the executive branch in at least two distinct (and interrelated) ways – first, through the exercise of executive discretion over appointments and second, through the attempts directly or indirectly to influence the 1 This chapter builds on an earlier study (see Sossin 2008), including a paper prepared for the first Workshop on Comparative Administrative Law, Yale University, May 2009, where I benefited from constructive and thought provoking comments on my paper and a lively exploration of comparative administrative law more generally. -

Core 1..172 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 145 Ï NUMBER 056 Ï 3rd SESSION Ï 40th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, June 4, 2010 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 3415 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, June 4, 2010 The House met at 10 a.m. we are now dealing with the Canada Post issue, which I just spoke about, and the fire sale of Atomic Energy of Canada Limited in Group No. 2. Prayers In terms of the Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, AECL, it is the largest crown corporation. This in itself, as I think everyone would GOVERNMENT ORDERS agree, would merit a separate bill because this particular crown corporation has had over $22 billion put into building the company. Ï (1005) There is a critical mass of expertise. [English] JOBS AND ECONOMIC GROWTH ACT The government is bent, we believe, on selling and privatizing The House resumed from June 3 consideration of Bill C-9, An AECL probably to an American firm, and just at a time when the Act to implement certain provisions of the budget tabled in nuclear industry is starting to become popular again. In some parts of Parliament on March 4, 2010 and other measures, as reported the world there are over 100 reactors being initiated on a global (without amendment) from the committee, and of the motions in basis. This industry in Canada is well known as a world leader in this Group No. 2. area. The Speaker: When the matter was last before the House, the hon. -

Canada's Northern Strategy Under Prime Minister Stephen Harper

Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security Canada’s Northern Strategy under Prime Minister Stephen Harper: Key Speeches and Documents, 2005-15 P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Ryan Dean Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security (DCASS) ISSN 2368-4569 Series Editors: P. Whitney Lackenbauer Adam Lajeunesse Managing Editor: Ryan Dean Canada’s Northern Strategy under the Harper Conservatives: Key Speeches and Documents on Sovereignty, Security, and Governance, 2005-15 P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Ryan Dean DCASS Number 6, 2016 Front Cover: Rt. Hon. Stephen Harper speaking during Op NANOOK 2012, Combat Camera photo IS2012-5105-06. Back Cover: Rt. Hon. Stephen Harper speaking during Op LANCASTER 2006, Combat Camera photo AS2006-0491a. Centre for Military, Security and Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Strategic Studies St. Jerome’s University University of Calgary 290 Westmount Road N. 2500 University Dr. N.W. Waterloo, ON N2L 3G3 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 519.884.8110 ext. 28233 Tel: 403.220.4030 www.sju.ca/cfpf www.cmss.ucalgary.ca Arctic Institute of North America University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW, ES-1040 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403-220-7515 http://arctic.ucalgary.ca/ Copyright © the authors/editors, 2016 Permission policies are outlined on our website http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/research/arctic-document-series Canada’s Northern Strategy under the Harper Government: Key Speeches and Documents on Sovereignty, Security, and Governance, 2005-15 P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. and Ryan Dean, M.A. Contents List of Acronyms ..................................................................................................... xx Introduction ......................................................................................................... xxv Appendix: Federal Cabinet Ministers with Arctic Responsibilities, 2006- 2015 ........................................................................................................ xlvi 1. -

Making Space for Reconciliation in Canada's Planning System

Making space for reconciliation in Canada's planning system by Lindsay Galbraith Darwin College University of Cambridge Master of Arts, Simon Fraser University, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, The University of Western Ontario, 2002 THIS DISSERTATION IS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of Geography September 2014 PREFACE PREFACE This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. No part of this dissertation has been submitted for any other qualification. This dissertation exceeds the prescribed limit of 80,000 words, excluding appendices and bibliography. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The PhD research process is often considered to be a solo project. However, this project could not have been completed without the support and love of numerous individuals and communities in several geographic locations. Most notable are those of you from Haida Gwaii. Many of you have shared your time, experiences, ideas, and knowledge with me. Others have been kind enough to offer advice and insights on my written work and ideas. Others still simply allowed me to learn from them. Howaa and Hawaa and Thank You, to all of you. I have truly changed as a result of what I have learned. I would particularly like to thank my supervisor, Professor Susan Owens, for her encouragement and patience in working with me. Your precision and analytical rigour are inspiring! A number of faculty and student colleagues have also been very helpful offering advice and reading through my work. To my family and friends who have supported me throughout the process, I feel truly blessed to have you in my life.