Where Would Libraries Be Without Readers? a Methodological Approach to Historical Literacy, Based on the Situation in Norway in the 18Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses

Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. The present study has been based as far as possible on primary sources such as protocols, letters, legal documents, and articles in journals, magazines, and newspapers from the nineteenth century. A contextual-comparative approach was employed to evaluate the objectivity of a given source. Secondary sources have also been consulted for interpretation and as corroborating evidence, especially when no primary sources were available. The study concludes that the Pietist revival ignited by the Norwegian Lutheran lay preacher, Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771-1824), represented the culmination of the sixteenth- century Reformation in Norway, and the forerunner of the Adventist movement in that country. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Nordic Broadband City Index 2012

Nordic Broadband City Index How cities facilitate a digital future June 2012 - Nexia DA - Nordic Broadband City Index Document history Title Nordic Broadband City Index Date and version June 2012 – Version 1.0 About this report The Nordic Broadband City Index has been prepared by Marit Wetterhus and Harald Wium Lie at Nexia DA on behalf of Telenor ASA and IKT-Norge in the period from January to May 2012. Special thanks to We would not have been able to obtain information on the Swedish market if it was not for Anna- Carin Mattson, Tommy Y. Andersson and Per Gundersen at Skanova, Stefan Albertsson at Eltel Networks, Mats Gustavson and Lars-Eric Gustavsson at TeliaSonera and several other people at Eltel Networks, TeliaSonera and Skanova. In Denmark Peder Hansen at Telcon was of invaluable importance, and we would also like to thank Anders Poulsen at Global Connect. In Norway we would like to thank Svein Nassvik, Herleik Johansen, Sverre Lysnes, Morten Skjelbred, at Sønnico, Roar Salen, in Eltel Networks and Tom Bakke Pedersen, Øystein Knudsen, Knut Beving and Erik Sikkeland in Relacom provided us with valuable information we needed in order to develop the index, and we are very grateful that they all took time out of their busy schedule to talk to us. We would also like to thank all the municipalities for their time and efforts, Liv Freihow at IKT-Norge and last, but not least the people in Telenor Denmark, Telenor Norway and Telenor Sweden and Erlend Bjørtvedt in Telenor Group for their support and expert knowledge. -

Revival and Society

REVIVAL AND SOCIETY An examination of the Haugian revival and its influence on Norwegian society in the 19th century. Magister Thesis in Sociology at the University of Oslo, 1978. By Alv Johan Magnus Grimerud 2312 Ottestad, Norway. Hans Nielsen Hauge, painted in 1800 Contents page Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: Hauge and his times 14 Chapter 3: Hauge and his message 23 Chapter 4: Hauge's work 36 Chapter 5: Revival in focus 67 Chapter 6: Social consequences of the revival 77 Chapter 7: The economic institution 83 Chapter 8: The political institution 95 Chapter 9: The religious institution 104 Chapter 10: Summing up 117 Literature 121 Foreword As I submit this thesis, it remains for me to give a special thank to my two supervisors, associate professor Sigurd Skirbekk and rector Otto Hauglin, for their personal involvement in my work. Our many talks and discussions have influenced this thesis. I also want to thank my fellow students for their constructive criticism during the writing periode. Rev. Einar Huglen has red the material on church history and given valuable corrections. A special thank goes to him. Elisabeth Engelsviken har accurately typed the whole manuscript, and Gro Bjerke has been of great help in drawing the figures. Thanks to both of you. Oslo, April 1, 1978. Alv J. Magnus PS: The painting above shows the only known original portrait of Hans Nielsen Hauge, probably made in Copenhagen in 1800. The English translation is done by Jenefer E. Hough, and the digital version by Steinar Thorvaldsen at Tromsø University College. A final part (Chapter 11-14) is only available in Norwegian, and is not included in this English version. -

Denmark and the Crusades 1400 – 1650

DENMARK AND THE CRUSADES 1400 – 1650 Janus Møller Jensen Ph.D.-thesis, University of Southern Denmark, 2005 Contents Preface ...............................................................................................................................v Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 Crusade Historiography in Denmark ..............................................................................2 The Golden Age.........................................................................................................4 New Trends ...............................................................................................................7 International Crusade Historiography...........................................................................11 Part I: Crusades at the Ends of the Earth, 1400-1523 .......................................................21 Chapter 1: Kalmar Union and the Crusade, 1397-1523.....................................................23 Denmark and the Crusade in the Fourteenth Century ..................................................23 Valdemar IV and the Crusade...................................................................................27 Crusades and Herrings .............................................................................................33 Crusades in Scandinavia 1400-1448 ..............................................................................37 Papal Collectors........................................................................................................38 -

978-951-44-9143-6.Pdf

GOOD BOOK, GOOD LIBRARY, GOOD READING Aušra Navickienė Ilkka Mäkinen Magnus Torstensson Martin Dyrbye Tiiu Reimo (eds) GOOD BOOK GOOD LIBRARY GOOD READING Studies in the History of the Book, Libraries and Reading from the Network HIBOLIRE and Its Friends Contents Preface .................................................................................. 7 Magnus Torstensson Introduction ......................................................................... 9 Good Book Elisabeth S. Eide The Nobleman, the Vicar and a Farmer Audience Norwegian Book History around 1800 ................................ 29 Lis Byberg What Were Considered to be Good Books in the Time of Popular Enlightenment? The View of Philanthropists Compared to the View of a Farmer ....................................... 52 Aušra Navickienė The Development of the Lithuanian Book in the First Half © 2013 Tampere University Press and Authors of the Nineteenth Century – A Real Development? .............. 76 Aile Möldre Page Design Maaret Kihlakaski Good Books at a Reasonable Cost – Mission of a Good Publisher: Cover Mikko Reinikka the Case of Eesti Päevaleht Book Series ................................ 108 ISBN 978-951-44-9142-9 ISBN 978.951-44-9143-6 (pdf) Good Library Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print Stefania Júliusdóttir Tampere 2013 Reading Societies in Iceland. Their foundation, Role, Finland and the Destiny of Their Book Collections ........................... 125 Contents Preface ................................................................................. -

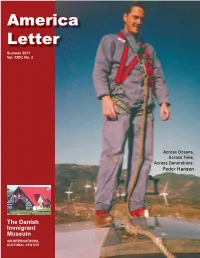

Peder Hansen

America Letter Summer 2011 Vol. XXIV, No. 2 Across Oceans, Across Time, Across Generations: Peder Hansen The Danish Immigrant Museum AN INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL CENTER Director’s Corner “The Danish Immigrant Museum celebrates Danish roots and American dreams.” Over the past year, the museum’s board of The stories of migration are dynamic narratives directors and staff have been working on a refl ecting a deep human instinct to improve strategic and operational plan that will guide individual and social conditions. us for the next fi ve years. (A summary of Elsewhere in the strategic plan is the goal to the strategic plan can be found on page 13.) partner with other Danish and Danish-American Among the goals discussed was articulating a organizations and institutions. Our new mission new mission statement. During the formulation statement challenges us to collaborate with of our plan, a number of mission statements all who work to “celebrate Danish roots and were discussed. American dreams.” Potentially, we can enhance At our June meeting in Denver, Henrik Fogh and strengthen each other by working together, Rasmussen, our youngest board member and even as we recognize that each organization has a recently naturalized American citizen, argued its own aspirations and dreams. persuasively that the statement should be short No organization or institution can thrive without and easily remembered. He, along with board fi nancial support. The Danish Immigrant Museum members Ane-Grethe Delaney and Kristi Planck depends on the generosity of its members. You, Johnson, proposed the above statement, which our members, have been loyal in renewing your was discussed and accepted with enthusiasm. -

Tracing the Jerusalem Code Vol. 3

Tracing the Jerusalem Code 3 Tracing the Jerusalem Code Volume 3: The Promised Land Christian Cultures in Modern Scandinavia (ca. 1750–ca. 1920) Edited by Ragnhild J. Zorgati and Anna Bohlin Illustrations edited by Therese Sjøvoll The research presented in this publication was funded by the Research Council of Norway (RCN), project no. 240448/F10 ISBN 978-3-11-063488-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063947-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063656-7 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110639476 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020952378 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Ragnhild Johnsrud Zorgati, Anna Bohlin (eds.), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image and frontispiece: Einar Nerman, cover design for Selma Lagerlöf’s novel Jerusalem, 18th edition, Stockholm: Bonniers, 1930. Photo credit: National Library of Sweden (Kungliga Biblioteket), Stockholm. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com In memory of Erling Sverdrup Sandmo (1963–2020) Acknowledgements This book is the result of research conducted within the project Tracing the Jerusalem Code –Christian Cultures in Scandinavia, financed by the Research Council of Norway and with support from MF Norwegian School of Theology, Religion and Society, the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages (University of Oslo), and the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. -

The Temple of Jerusalem

Tracing the Jerusalem Code 2 Tracing the Jerusalem Code Volume 2: The Chosen People Christian Cultures in Early Modern Scandinavia (1536–ca. 1750) Edited by Eivor Andersen Oftestad and Joar Haga The research presented in this publication was funded by the Research Council of Norway (RCN), project no. 240448/F10 ISBN 978-3-11-063487-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063945-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063654-3 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110639452 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020951833 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Eivor Andersen Oftestad, Joar Haga (eds), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: New Jerusalem. Detail of epitaph, ca. 1695, Ringkøbing Church, Denmark. Photo: National Museum of Denmark (Nationalmuseet), Copenhagen, Arnold Mikkelsen. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI Books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com In memory of Erling Sverdrup Sandmo (1963–2020) Contents List of Maps and Illustrations XI List of Abbreviations XVII Editorial comments for all three volumes XIX Kristin B. Aavitsland, Eivor Andersen Oftestad, and -

Winter 2018 | a Benefit of Membershipletter in the Museum of Danish America

americaWINTER 2018 | A BENEFIT OF MEMBERSHIPletter IN THE MUSEUM OF DANISH AMERICA How the events of 1918 shaped a Danish-American family. INSIDE More stories of war and peace contents ENDINGS14 & BEGINNINGS RESISTING23 IN WWII 32BIKING VIKINGS 38WARTIME MEMORIES 04 Director’s Corner 23 Occupation and 41 News in Brief Resistance 06 Survey Results 27 Exhibits 42 New Members and Old Friends 08 Nordic DC 28 Collection Connection 10-Year Interns 11 Events Calendar 30 CAP Program 46 12 Meeting in Elk Horn 32 Bicycle Tour 48 Holiday Craft 14 Across Oceans, 38 Wartime Tales Across Time, Across Generations ON THE COVER America Letter Winter 2018, No. 3 John and Meta Nielsen suff ered extraordinary Published three times annually by the Museum of Danish America hardships before fi nding each other and building 2212 Washington Street, Elk Horn, Iowa 51531 their family. Read about it, beginning on page 14. 712.764.7001, 800.759.9192, Fax 712.764.7002 danishmuseum.org | [email protected] 2 staff & interns Executive Director Building & Grounds Manager Administrative Assistant Rasmus Thøgersen, M.L.I.S. Tim Fredericksen Terri Amaral E: rasmus.thoegersen E: tim.fredericksen E: terri.amaral Administrative Manager Albert Ravenholt Curator of Genealogy Center Manager Terri Johnson Danish-American Culture Kara McKeever, M.F.A. E: terri.johnson Tova Brandt, M.A. E: kara.mckeever E: tova.brandt Development Manager Genealogy Assistant Deb Christensen Larsen Curator of Collections Wanda Sornson, M.S. E: deb.larsen & Registrar E: wanda.sornson Angela Stanford, M.A. Communications Specialist, E: angela.stanford Executive Director Emeritus America Letter Editor John Mark Nielsen, Ph.D. -

Sixtus Von Møinichen #1, Born in Rostock, Germany. I. Claus Von

Sixtus von Møinichen #1, born in Rostock, Germany. I. Claus von Møinichen #2, born in Rostock, Germany. A. Andreas von Møinichen #3, born in Rostock, Germany. He married Margaretha #6. 1. Andreas von Møinichen #4, born in Rostock, Germany. He married Anna #5. a. Sixtus von Møinichen #7, born 1539 in Rostock, Germany. He married Barbara Göde #8, born Mar 1573 in Gnoien, Mecklenburg, Germany, (daughter of Morten Göde #9 and Juditte Sleueske #201) died 22 Mar 1639 in Ystad, Sweden. Sixtus died 7 Mar 1613 in Ystad, Sweden. (1) Morten Sixen von Møinichen #10, born 16 May 1599 in Ystad, Denmark (today Sweden). He married Margaretha Hindrichdatter Dabelsten #11, married 14 Oct 1627 in Malmoe, Denmark (today Sweden), born 04 Jan 1608 in Malmø, Sweden, (daughter of Hendrich Dabelsten #18 and Karne Jensdatter #19) baptized in St. Peders Church, Malmoe, died 01 Sep 1677 in Copenhagen, Denmark, buried in the chapel of Hellig Geist Church. Morten died 13 May 1663 in Copenhagen, Denmark. (a) Sixtus Mortensen von Møinichen #12, born 16 May 1629 in Malmoe, baptized 22 May 1629. He married Anna Clausdatter Thiesen #13. Sixtus died 1666. [1] Margrethe von Møinichen #22. [2] Claus von Møinichen #20, born 1666 in Denmark. He married Cathrine Frederiksdatter Pohlmann #21. Claus died 1726 in Copenhagen, Denmark. (b) Henrich Mortensen von Møinichen #23, born 04 Jan 1631 in Malmø, baptized 09 Jan 1631. He married (1) Ingeborg Wernersdatter Klaumann #204, married 19 Jun 1666 in Copenhagen, born 1642 in Copenhagen, Denmark, (daughter of Werner Klaumann #205 and Ingeborg Mecklenborg Mathiesdatter #206) died 15 Jul 1672 in Copenhagen, buried 26 Jul 1672 in the choir of Hellig Geist Church. -

Norwegians in New York, 1825-1925

Ex Safaris SEYMOUR DURST When you leave, please leave this book Because it has been said "Ever'thing comes t' him who waits Except a loaried book." Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library Gift of Seymour B. Durst Old York Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/norwegiansinnewyOOrygg NORWEGIANS IN NEW YORK 1825-1925 By A. N. RYGG, LL.D. Commander of the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav Former Editor of the Norwegian News PUBLISHED BY THE NORWEGIAN NEWS COMPANY BROOKLYN, N. Y. This boo\ is respectfully dedicated to the people of Norwegian descent with whom I have had the privi- lege and honor to wor\ during many happy years. A. N. RYGG PRINTED IN U.S.A. ARNESEN PRESS, INC., BROOKLYN, N.Y. INTRODUCTION THE Norwegian Community in New York City is now more than a century old, figuring from the time of the arrival of the sloop Restau- rationen, which often and with justification has been called the Norwegian May')'lower. For about 115 years Norwegians have been part and parcel of this community and have made their substantial contributions to the upbuilding of the City and the land. These contributions to what may be called the Making of America have on the part of the Norwegian ele- ment embraced nearly every field of human endeavor, although it is quite natural that in the Port of New York and along the Atlantic seaboard as a whole the heaviest contribution to American life and development has been in shipping in all its various phases.