978-951-44-9143-6.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the Opening of the Academic Year on 10 September 2019

1 Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the opening of the academic year on 10 September 2019 Honoured guests, dear colleagues, alumni and friends of Tampere University. It is my great pleasure to welcome you all to celebrate the opening of our University’s first academic year! The idea to establish a unique new higher education community in Tampere can be traced back to more than five years ago when it was first formulated during discussions involving Kai Öistämö, Tero Ojanperä and Matti Höyssä, who presided over the Boards of the three Tampere- based higher education institutions, and then-Presidents of the institutions Kaija Holli, Markku Kivikoski and Markku Lahtinen. In spring 2014, the three institutions commissioned Stig Gustavson to identify areas where they could establish a leading international reputation and determine the necessary steps to achieve this vision. The 21 founding members signed the Charter of Tampere University Foundation on 20 April 2017. As set out in the Charter, the old, distinguished University of Tampere and Tampere University of Technology were to be merged to create a new university with the legal status of a foundation. The new university was also to become the majority shareholder of Tampere University of Applied Sciences. The agreement whereby the City of Tampere assigned its ownership of Tampere University of Applied Sciences Ltd to Tampere University Foundation was signed on 15 February 2018. Our new Tampere University started its operations at the beginning of this year. Today marks the 253rd day since the launch of the youngest university in Finland and in Europe. -

EAA Meeting 2016 Vilnius

www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME Organisers CONTENTS President Words .................................................................................... 5 Welcome Message ................................................................................ 9 Symbol of the Annual Meeting .............................................................. 13 Commitees of EAA Vilnius 2016 ............................................................ 14 Sponsors and Partners European Association of Archaeologists................................................ 15 GENERAL PROGRAMME Opening Ceremony and Welcome Reception ................................. 27 General Programme for the EAA Vilnius 2016 Meeting.................... 30 Annual Membership Business Meeting Agenda ............................. 33 Opening Ceremony of the Archaelogical Exhibition ....................... 35 Special Offers ............................................................................... 36 Excursions Programme ................................................................. 43 Visiting Vilnius ............................................................................... 57 Venue Maps .................................................................................. 64 Exhibition ...................................................................................... 80 Exhibitors ...................................................................................... 82 Poster Presentations and Programme ........................................... -

Friends of the National Libraries: a Short History

Friends of the National Libraries: A Short History Saving the nation’s written and By Max Egremont printed heritage This history first appeared in a special edition of The Book Collector in Summer 2011, FNL’s eightieth year. The Trustees of Friends of the National Libraries are grateful to the publisher of The Book Collector for permission to reissue the article in its present, slightly amended, form. A Short History 1 HRH The Prince of Wales. © Hugo Burnand. 2 Friends of the National Libraries Friends of the National he Friends of the National Libraries began as a response to an emergency. From the start, the Friends were fortunate in their leadership. Sir Frederic Libraries has helped save TOn March 21 1931, the Times published a letter signed by a group of the great Kenyon was one of British Museum’s great directors and principal librarians, the nation’s written and and the good, headed by the name of Lord D’Abernon, the chairman of the Royal a classical and biblical scholar who made his name as a papyrologist and widened the printed history since Commission on National Museums and Galleries. The message was that there was appeal of the museum by introducing guide lecturers and picture postcards; he also had a need for an organisation similar to the National Art Collections Fund (now called literary credentials as the editor of the works of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. 1931. FNL awards grants the Art Fund) but devoted to rare books and manuscripts. The reason for this The Honorary Treasurer Lord Riddell, a former associate of Lloyd George, came to national, regional was that sales of rare books and manuscripts from Britain to institutions and to from the world of politics and the press. -

European and National Dimension in Research

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION OF BELARUS Polotsk State University EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL DIMENSION IN RESEARCH ЕВРОПЕЙСКИЙ И НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ КОНТЕКСТЫ В НАУЧНЫХ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯХ MATERIALS OF VI JUNIOR RESEARCHERS’ CONFERENCE (Novopolotsk, April 22 – 23, 2014) In 3 Parts Part 1 HUMANITIES Novopolotsk PSU 2014 UDC 082 Publishing Board: Prof. Dzmitry Lazouski ( chairperson ); Dr. Dzmitry Hlukhau (vice-chairperson ); Mr. Siarhei Piashkun ( vice-chairperson ); Dr. Maryia Putrava; Ms. Liudmila Slavinskaya Редакционная коллегия : д-р техн . наук , проф . Д. Н. Лазовский ( председатель ); канд . техн . наук , доц . Д. О. Глухов ( зам . председателя ); С. В. Пешкун ( зам . председателя ); канд . филол . наук , доц . М. Д. Путрова ; Л. Н. Славинская The first two conferences were issued under the heading “Materials of junior researchers’ conference”, the third – “National and European dimension in research”. Junior researchers’ works in the fields of humanities, social sciences, law, sport and tourism are presented in the second part. It is intended for trainers, researchers and professionals. It can be useful for university graduate and post- graduate students. Первые два издания вышли под заглавием « Материалы конференции молодых ученых », третье – «Национальный и европейский контексты в научных исследованиях ». В первой части представлены работы молодых ученых по гуманитарным , социальным и юридиче- ским наукам , спорту и туризму . Предназначены для работников образования , науки и производства . Будут полезны студентам , маги- странтам и аспирантам университетов . ISBN 978-985-531-444-9 (P. 1) © Polotsk State University, 2014 ISBN 978-985-531-443-2 MATERIALS OF V JUNIOR RESEARCHERS’ CONFERENCE 2014 Linguistics, Literature, Philology LINGUISTICS, LITERATURE, PHILOLOGY UDC 821.111.09=111 THE DECONSTRUCTION OF GENDER ROLES IN "THE GRAPES OF WRATH" BY JOHN STEINBECK ON THE EXAMPLE OF MA JOAD LIZAVETA BALSHAKOVA, DZYANIS KANDAKOU Polotsk State University, Belarus The Grapes of Wrath, has been read and reread by millions, pondered and set down in a thousand essays and books. -

Highland City Library: Long-Range Strategic Plan 2019-2022

Highland City Library: Long-range Strategic Plan 2019-2022 Introduction Public libraries have long been an important aspect of American life. From the early days of the Republic, libraries were valued by Americans. Benjamin Franklin founded the first subscription library in Philadelphia in 1732 with fifty members to make books more available for citizens of the young nation. From that time to the present, public libraries have been valued because they allow equal access to information and educational resources regardless of social or economic status. Library service has long been important to the residents of Highland. From 1994 to 2001, residents of Highland and Alpine were served by a joint use facility at Mountain Ridge Junior High School. That arrangement was eventually terminated and in 2001 the entire library collection was relocated to the old Highland City building for storage. In 2008, Highland City built a new city hall and dedicated a portion of the building for a city Library. In 2016 the Library received permission to convert a public meeting room into a Children’s Room for the Library. The new Children’s Room was opened in spring of 2018. The Library joined the North Utah County Library Cooperative (NUCLC) April 1, 2012 as an associate member. NUCLC is a reciprocal borrowing system that allows library card holders from participating libraries to check out materials from other participating libraries. It is not a county library system. Each participating library maintains its own policies, budget, administration, non-resident fees, etc. In 2018 the Library reached the required collection size and was accepted as a full NUCLC member. -

Leading a Fundamentally Detuned Choir: University of Tampere, Finland – a Civic University?

[Draft chapter – will be published in Goddard, J., Hazelkorn, E., Kempton, L. & Vallance, P. The Civic University: the Policy and Leadership Challenges. Edwar Elgar.] Markku Sotarauta Leading a Fundamentally Detuned Choir: University of Tampere, Finland – A Civic University? 1 Introduction A university is an academic ensemble of scholars who are specialised and deeply dedicated to a particular branch of study. Often scholars are passionate about what they do, and are willing to listen only to those people they respect, that is their colleagues and peers, but not necessarily heads of their departments, faculties or research centres. Despite many efforts, university leaders more often than not find it difficult to make academic ensembles sing the same song. If a group of singers perform together, it is indeed a choir. A community of scholars is not necessarily so. Singers agree on what to sing and how, they know their sheets, and a choir leader conducts them. A community of scholars, however, is engaged in a continuous search for knowledge through the process of thesis and antithesis, debates, as well as conflicts and fierce rivalry – without an overarching conductor. Universities indeed are different sorts of ensembles, as scholars may not agree about what is and is not important for a university as a whole. By definition a university is not a well-tuned chorus but a proudly and fundamentally detuned one. Leadership in, and of, this kind of organic entity is a challenge in itself, not to mention navigating the whole spectrum of existing and potential stakeholders. Cohen and March (1974) see universities as ‘organized anarchies’, as the faculty members’ personal ambitions and goals as well as fluid participation in decision- making suggest that universities are managed in decidedly non-hierarchical terms, but still within the structure of a formally organised hierarchy. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

Nordic Broadband City Index 2012

Nordic Broadband City Index How cities facilitate a digital future June 2012 - Nexia DA - Nordic Broadband City Index Document history Title Nordic Broadband City Index Date and version June 2012 – Version 1.0 About this report The Nordic Broadband City Index has been prepared by Marit Wetterhus and Harald Wium Lie at Nexia DA on behalf of Telenor ASA and IKT-Norge in the period from January to May 2012. Special thanks to We would not have been able to obtain information on the Swedish market if it was not for Anna- Carin Mattson, Tommy Y. Andersson and Per Gundersen at Skanova, Stefan Albertsson at Eltel Networks, Mats Gustavson and Lars-Eric Gustavsson at TeliaSonera and several other people at Eltel Networks, TeliaSonera and Skanova. In Denmark Peder Hansen at Telcon was of invaluable importance, and we would also like to thank Anders Poulsen at Global Connect. In Norway we would like to thank Svein Nassvik, Herleik Johansen, Sverre Lysnes, Morten Skjelbred, at Sønnico, Roar Salen, in Eltel Networks and Tom Bakke Pedersen, Øystein Knudsen, Knut Beving and Erik Sikkeland in Relacom provided us with valuable information we needed in order to develop the index, and we are very grateful that they all took time out of their busy schedule to talk to us. We would also like to thank all the municipalities for their time and efforts, Liv Freihow at IKT-Norge and last, but not least the people in Telenor Denmark, Telenor Norway and Telenor Sweden and Erlend Bjørtvedt in Telenor Group for their support and expert knowledge. -

Światowit. Volume LVII. World Archaeology

Światowit II LV WIATOWIT S ´ VOLUME LVII WORLD ARCHAEOLOGY Swiatowit okl.indd 2-3 30/10/19 22:33 Światowit XIII-XIV A/B_Spis tresci A 07/11/2018 21:48 Page I Editorial Board / Rada Naukowa: Kazimierz Lewartowski (Chairman, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Serenella Ensoli (University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Italy), Włodzimierz Godlewski (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Joanna Kalaga ŚŚwiatowitwiatowit (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Mikola Kryvaltsevich (Department of Archaeology, Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Belarus), Andrey aannualnnual ofof thethe iinstitutenstitute ofof aarchaeologyrchaeology Mazurkevich (Department of Archaeology of Eastern Europe and Siberia, The State Hermitage ofof thethe uuniversityniversity ofof wwarsawarsaw Museum, Russia), Aliki Moustaka (Department of History and Archaeology, Aristotle University of Thesaloniki, Greece), Wojciech Nowakowski (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, ocznikocznik nstytutunstytutu rcheologiircheologii Poland), Andreas Rau (Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, Schleswig, Germany), rr ii aa Jutta Stroszeck (German Archaeological Institute at Athens, Greece), Karol Szymczak (Institute uuniwersytetuniwersytetu wwarszawskiegoarszawskiego of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland) Volume Reviewers / Receznzenci tomu: Jacek Andrzejowski (State Archaeological Museum in Warsaw, Poland), Monika Dolińska (National Museum in Warsaw, Poland), Arkadiusz -

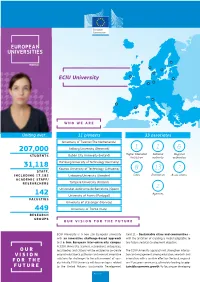

ECIU University

ECIU University WHO WE ARE Uniting over… 11 pioneers 33 associates University of Twente (The Netherlands) 1 1 6 207,000 Aalborg University (Denmark) Dublin City University (Ireland) Higher Education National Regional STUDENTS Institution authority authorities Hamburg University of Technology (Germany) 31,118 Kaunas University of Technology (Lithuania) 8 13 2 STAFF, INCLUDING 17,182 Linköping University (Sweden) Cities Enterprises Associations ACADEMIC STAFF/ Tampere University (Finland) RESEARCHERS 2 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain) Agencies 142 University of Aveiro (Portugal) FACULTIES University of Stavanger (Norway) 449 University of Trento (Italy) RESEARCH GROUPS OUR VISION FOR THE FUTURE ECIU University is a new pan-European university Goal 11 – Sustainable cities and communities – with an innovative challenge-based approach with the ambition of creating a model adaptable to and a true European inter-university campus. any future societal development objective. At ECIU University, learners, researchers, enterprises, OUR local bodies and citizens will be enabled to co-create The ECIU University approach will strengthen interac- VISION original educational pathways and relevant innovative tion and engagement among education, research and solutions for challenges to the advancement of soci- innovation, with a positive effect on the local, regional FOR THE ety. Initially, ECIU University will focus on topics related and European community, ultimately leading to sus- FUTURE to the United Nations Sustainable Development tainable -

Revival and Society

REVIVAL AND SOCIETY An examination of the Haugian revival and its influence on Norwegian society in the 19th century. Magister Thesis in Sociology at the University of Oslo, 1978. By Alv Johan Magnus Grimerud 2312 Ottestad, Norway. Hans Nielsen Hauge, painted in 1800 Contents page Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: Hauge and his times 14 Chapter 3: Hauge and his message 23 Chapter 4: Hauge's work 36 Chapter 5: Revival in focus 67 Chapter 6: Social consequences of the revival 77 Chapter 7: The economic institution 83 Chapter 8: The political institution 95 Chapter 9: The religious institution 104 Chapter 10: Summing up 117 Literature 121 Foreword As I submit this thesis, it remains for me to give a special thank to my two supervisors, associate professor Sigurd Skirbekk and rector Otto Hauglin, for their personal involvement in my work. Our many talks and discussions have influenced this thesis. I also want to thank my fellow students for their constructive criticism during the writing periode. Rev. Einar Huglen has red the material on church history and given valuable corrections. A special thank goes to him. Elisabeth Engelsviken har accurately typed the whole manuscript, and Gro Bjerke has been of great help in drawing the figures. Thanks to both of you. Oslo, April 1, 1978. Alv J. Magnus PS: The painting above shows the only known original portrait of Hans Nielsen Hauge, probably made in Copenhagen in 1800. The English translation is done by Jenefer E. Hough, and the digital version by Steinar Thorvaldsen at Tromsø University College. A final part (Chapter 11-14) is only available in Norwegian, and is not included in this English version. -

Michigan Libraries

Michigan Time Traveler Michigan Time Traveler An educational supplement produced by Lansing Newspapers In Education, Inc. and the Michigan Historical Center. Read This Summer! Until the 20th century, children under the age of 10 were not allowed to use most libraries. Other than nursery rhymes, there weren’t many books for kids. Today that has changed! Libraries have neat areas for kids with books, activities, even computers! Every summer millions of kids read for fun. By joining a summer reading program at their local library, they get free stuff and win prizes. Jim — “the Spoon Man” KIDS’KIDS’ — Cruise (photo, center) says reading is like exercising, “Whenever you read a book, I call it ‘lifting weights for your brain.’” This year many Michigan libraries are celebrating “Laugh It Up @ History Your Library.” These libraries History have lots of books good for laughing, learning and just loafing this summer. The Spoon aries Man had everybody laughing at Time Lansing’s Libraries the Capital Area District higan Libr s Lansing’s first library was a subscription library. Library Summer Reading Mic This month’ During the 1860s, the Ladies’ Library and Program kickoff. After One of the best ways to be a Literary Association started a library on West the program Traveler is to read a book. Michigan Avenue for its members. It cost $2 to Marcus and me Traveler explores the history of belong, and the library was open only on Lindsey (above left) Ti Saturdays. Then, in 1871, the Lansing Board of joined him to look places filled with books — libraries.