Leading a Fundamentally Detuned Choir: University of Tampere, Finland – a Civic University?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the Opening of the Academic Year on 10 September 2019

1 Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the opening of the academic year on 10 September 2019 Honoured guests, dear colleagues, alumni and friends of Tampere University. It is my great pleasure to welcome you all to celebrate the opening of our University’s first academic year! The idea to establish a unique new higher education community in Tampere can be traced back to more than five years ago when it was first formulated during discussions involving Kai Öistämö, Tero Ojanperä and Matti Höyssä, who presided over the Boards of the three Tampere- based higher education institutions, and then-Presidents of the institutions Kaija Holli, Markku Kivikoski and Markku Lahtinen. In spring 2014, the three institutions commissioned Stig Gustavson to identify areas where they could establish a leading international reputation and determine the necessary steps to achieve this vision. The 21 founding members signed the Charter of Tampere University Foundation on 20 April 2017. As set out in the Charter, the old, distinguished University of Tampere and Tampere University of Technology were to be merged to create a new university with the legal status of a foundation. The new university was also to become the majority shareholder of Tampere University of Applied Sciences. The agreement whereby the City of Tampere assigned its ownership of Tampere University of Applied Sciences Ltd to Tampere University Foundation was signed on 15 February 2018. Our new Tampere University started its operations at the beginning of this year. Today marks the 253rd day since the launch of the youngest university in Finland and in Europe. -

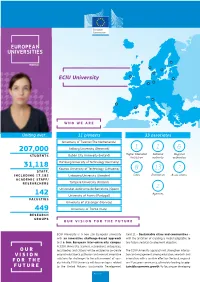

ECIU University

ECIU University WHO WE ARE Uniting over… 11 pioneers 33 associates University of Twente (The Netherlands) 1 1 6 207,000 Aalborg University (Denmark) Dublin City University (Ireland) Higher Education National Regional STUDENTS Institution authority authorities Hamburg University of Technology (Germany) 31,118 Kaunas University of Technology (Lithuania) 8 13 2 STAFF, INCLUDING 17,182 Linköping University (Sweden) Cities Enterprises Associations ACADEMIC STAFF/ Tampere University (Finland) RESEARCHERS 2 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain) Agencies 142 University of Aveiro (Portugal) FACULTIES University of Stavanger (Norway) 449 University of Trento (Italy) RESEARCH GROUPS OUR VISION FOR THE FUTURE ECIU University is a new pan-European university Goal 11 – Sustainable cities and communities – with an innovative challenge-based approach with the ambition of creating a model adaptable to and a true European inter-university campus. any future societal development objective. At ECIU University, learners, researchers, enterprises, OUR local bodies and citizens will be enabled to co-create The ECIU University approach will strengthen interac- VISION original educational pathways and relevant innovative tion and engagement among education, research and solutions for challenges to the advancement of soci- innovation, with a positive effect on the local, regional FOR THE ety. Initially, ECIU University will focus on topics related and European community, ultimately leading to sus- FUTURE to the United Nations Sustainable Development tainable -

S34growth Kickoff Event 15-17 June 2016, Tampere, Finland

S34Growth kickoff event 15-17 June 2016, Tampere, Finland AGENDA Wednesday 15 June 2016 VENUE: Original Sokos Hotel Ilves, Sarka Cabinet, Hatanpään valtatie 1, 33100 Tampere Time Agenda 9:00 Project steering group meeting 10:15 Introduction to the OSDD Process Mr. James Coggs, Senior Executive, Strategy and Sectors - Appraisal and Evaluation, Scottish Enterprise Presentation of the baseline analysis Michael Johnsson, Senior EU Policy Officer, Skåne European Office 12:00 Lunch S34Growth kickoff seminar Moderator: Ms. Hannele Räikkönen, Director, Tampere Region EU Office 13:00 Opening Mr. Esa Halme, Region Mayor, Council of Tampere Region 13:10 Video greeting from the S34Growth financier Ms. Aleksandra Niechajowicz, Interreg Europe's Secretariat, Lille, France 1 13:20 Regional development and innovation policies in Tampere Region Mr. Jukka Alasentie, Director, Regional Development, Council of Tampere Region 13:40 Development of industrial value chains in Tampere Region Dr. Kari Koskinen, Professor, Head of Department, Mechanical Engineering and Industrial Systems, Tampere University of Technology 14:00 Experiences and opportunities of the Vanguard Initiative - New growth through smart specialisation Dr. Reijo Tuokko, Emeritus Professor, Mechanical Engineering and Industrial Systems,Tampere University of Technology 14:20 Coffee break 14:40 S34Growth - Enhancing policies through interregional cooperation: New industrial value chains for growth Mr. Esa Kokkonen, Director, The Baltic Institute of Finland, S34Growth Lead Partner 15:00 European -

Tampere University Exchange Studies Fact Sheet

Tampere University City centre, Hervanta and Kauppi campuses academic year 2021-2022 International Mobility Services • Full name of the institution: Tampere University • Erasmus+ code: SF TAMPERE17 • Contact us: [email protected] • Exchange coordinators: www.tuni.fi/en/about-us/international-mobility-services • Application instructions: www.tuni.fi/exchange • Student’s Guide: www.tuni.fi/studentsguide/tau-exchange • Mailing address: International Mobility Services, 33014 Tampere University • Visiting address: Kalevantie 4, 33100 Tampere • University merger: University of Tampere (UTA) merged with Tampere University of Technology (TUT) creating a new Tampere University in January 2019. Please note that @tut.fi and @uta.fi email addresses are not in use anymore; Tampere University of Applied Sciences (TAMK) is a separate higher education institution and not a part of the university Nomination periods and application deadlines Time of Nomination period Application deadline exchange studies Autumn semester 2021 (Aug–Dec) or 1 Mar – 15 Apr 2021 30 Apr 2021 whole academic year 2021–2022 (Aug–May) Spring semester 2022 15 Aug– 30 Sept 2021 15 Oct 2021 (Jan–May) We only accept online nominations. The link to the online application form will be sent to the nominated students by email. Campuses at Tampere University Tampere University has three campuses: in the city centre, Hervanta and Kauppi in Tampere. The city centre campus is a hub for education, business and management studies, natural sciences, life sciences, politics, communication, and social sciences. Hervanta campus and the surrounding area constitute a major technology hub and is a main campus for engineering students. The Kauppi campus is located near the Tampere University Hospital and is the home base for medicine and health sciences. -

Dear Partner, the University of Tampere Organises an Erasmus

Dear Partner, The University of Tampere organises an Erasmus Staff Exchange Week for the staff members of UTA's all Erasmus Partner Universities on 27 - 31 May 2013. During the week, participants will have an opportunity to benchmark different services and practices of the University and share views on topics related to their own work. In addition to a general introduction to the University of Tampere, the particants can choose the thematic tracks they wish to attend and the units they would like to visit from several different options. Furthermore, visits to Tampere University of Technology as well as to Tampere University of Applied Sciences are included in the programme. This year the thematic tracks are the following: Option 1: Curricula Planning and Student Services Option 2: International Services Option 3: Library Services Please find the preliminary programme enclosed. The registration for the week closes on Friday 25 January 2013. The electronic registration form is available at https://elomake3.uta.fi/lomakkeet/8789/lomake.html The number of participants is restricted to 20. Therefore, we will primarily accept one participant per partner institution and may not be able to accept all applicants. We shall announce the list of selected participants to all applicants per e-mail by 8 February 2013. We would also like to use this opportunity to thank all of you for the fruitful cooperation in the past year and look forward to continuing our collaboration next year. Yours sincerely Noora Maja and Pauliina Järvinen-Alenius -- Erasmus Mobility / room A110 International Office FI-33014 University of Tampere Tel. -

22–25 August 2012

First Announcement 4th International Dry Toilet Conference 22–25 August 2012 University of Tampere, Finland are warmly welcome to the 4th International Dry Toilet Conference to You be held in Tampere, Finland on 22nd to 25th of August 2012. The three previous conferences were succesful and inspired us to keep on organizing this international event in the field of sustainable sanitation. We wish it will bring forth fruitful ideas and policies around the world. Global Dry Toilet Association of Finland | www.drytoilet.org/dt2012 ProPosAls For PAPers the main theme of the conference will be “Drivers for ecological dry toilets in urban and rural areas” oral and poster presentations will be chosen by the scientific committeeon the basis of abstracts received. the deadline for abstract submission is 15 January 2012. the length of the abstract is 300 - 500 words fitted on one A4 format page. the official language of the conference is english. © sari Huuhtanen © erkki Karén conFerence venue the conference will be organised in tampere, the third largest city in Finland with a population of 213 000. tampere is a city of commerce, technology, arts and sciences as well as an important educational centre laying between two beautiful lakes and partly on top of an imposing ridge. For further information, please visit the city’s website for tourists (in english and russian) » here! tourist Brochures in PDF-format are published also in swedish, german, spanish, italian, French and Japanese. Hard copies of the brochures can be ordered free of charge at the Visit Tampere Brochure order site. the venue of the conference is the university of tampere. -

Daughters of the Vale of Tears

TUULA-HANNELE IKONEN Daughters of the Vale of Tears Ethnographic Approach with Socio-Historical and Religious Emphasis to Family Welfare in the Messianic Jewish Movement in Ukraine 2000 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the board of the School of Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Väinö Linna-Auditorium K104, Kalevantie 5, Tampere, on February 27th, 2013, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Social Sciences and Humanities Finland Copyright ©2013 Tampere University Press and the author Distribution Tel. +358 40 190 9800 Bookshop TAJU [email protected] P.O. Box 617 www.uta.fi/taju 33014 University of Tampere http://granum.uta.fi Finland Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1809 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1285 ISBN 978-951-44-9059-0 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9060-6 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://acta.uta.fi Tampereen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print Tampere 2013 Abstract This ethnographic approach with socio•historical and religious emphasis focuses on the Mission view of Messianic Jewish women in Ukraine circa 2000. The approach highlights especially the meaning of socio•historical and religious factors in the emergence of the Mission view of Messianic Jewish women. Ukraine, the location of this study case, is an ex•Soviet country of about 48 million citizens with 100 ethnic nationalities. Members of the Jewish Faith form one of those ethnic groups. Following the Russian revolution in 1989 and then the establishing of an independent Ukraine in 1991, the country descended into economic disaster with many consequent social problems. -

Tampere, Finland

Proposal to hold the 23RD INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES on 21–30 August 2020 in Tampere, Finland Proposal to hold the 23RD INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES on 21–30 August 2020 in Tampere, Finland CONTENTS Letter of Invitation from the University of Tampere ................................................................................. 3 Letter of Invitation from CISH National Committee (Finnish Historical Society) ................................................. 4 Letter of Invitation from the City of Tampere ........................................................................................ 5 Why Finland – Why Tampere ............................................................................................................. 6 University of Tampere .................................................................................................................... 7 Congress organization ..................................................................................................................... 8 Finances ................................................................................................................................... 10 Finland – your host country............................................................................................................. 11 Tampere – the congress city ........................................................................................................... 12 Travel to the congress site ............................................................................................................ -

Imagining a New Society

TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SARJA - SER. B OSA - TOM. 358 HUMANIORA Johanna Ruohonen IMAGINING A NEW SOCIETY Public Painting as Politics in Postwar Finland TURUN YLIOPISTO UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Turku 2013 From the Department of Art History School of History, Culture and Arts Studies University of Turku FIN-20014 Turku Finland Supervisors Professor Altti Kuusamo University of Turku Dr. Anja Kervanto Nevanlinna, Senior Research Fellow University of Helsinki Pre-examiners Professor Jonathan Harris Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton Dr. Liisa Lindgren University of Helsinki Opponent Dr. Liisa Lindgren University of Helsinki Custos Professor Altti Kuusamo University of Turku Layout: Päivi Valotie On the cover: Tove Jansson, “Electricity”, 1945. Oil on insulate board, 286 x 213 cm. Helsinki Art Museum. Photo: Hanna Riikonen, Helsinki Art Museum. ISBN 978-951-29-5293-9 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-5294-6 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 Painosalama Oy – Turku, Finland 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Preface: Re-visioning the Invisible 9 I PUBLIC PAINTING IN THE SOCIETY AND IN ART HISTORY 1. The Politics of Public Painting Monumental Painting as Public Art 15 Being Public 17 Private Sector Public Painting 23 Public Art and Agency 26 Monumental Memories: Art in Remembering and Forgetting 29 Setting the Framework 32 2. Public Painting in Art History Mural, Monumental, or Public? 36 Between High Art and Decoration 38 National Art in an International Context 41 The Uninteresting Public Painting 47 Building a Tradition (of Ignoring Public Paintings) 49 II FORMULATING NATIONAL ART 3. Picturing Ideologies Nationalism and the Early Finnish Public Painting 57 Realising an Ideology 62 National and Foreign 68 Addressing a Divided Nation 75 On a Lighter Tone 82 National Character for Art 87 “Art for the People” 94 4. -

Kautonen Transformation of Tampere 22.8

Transformation of Tampere and its innovation policy [email protected] Content 1. Introduction: background, motivation and goals 2. Industrial heritage 3. Formative years of the regional innovation system 4. Crisis to growth with explicit innovation policy 5. Latest developments in innovation policy 6. Some conclusions Transformation of Tampere and its innovation policy 1. Introduction: background, motivation and goals • Where are we actually? What kind of a city is Tampere? How did it become as it is nowadays? • Spatial perspective on innovation (& policy), specifically local/regional • Goal I: to increase understanding through a case of Tampere on possibilities, limits, instruments etc. of regional innovation policy • Goal II: to briefly scrutinize, as group works, what lessons might be adopted to different contexts, and what might be difficult and why. • Group work will be based on my presentation and Mika Raunio’s presentation. Transformation of Tampere and its innovation policy Presentation partly based on e.g. following publications: • Kautonen, M. (2012). Balancing Competitiveness and Cohesion in Regional Innovation Policy – The Case of Finland, European Planning Studies, Vol. 20, 12, pp. 1925-43. • Sotarauta, M. & Kautonen, M. (2007). Co-evolution of the Finnish National and Local Innovation and Science Arenas: Towards a Dynamic Understanding of Multi-Level Governance. Regional Studies, Special Issue on Regional Governance and Science Policy, Vol. 41.8, pp. 1–14. • Kautonen, M. (2006). Regional Innovation System Bottom-up: A Finnish Perspective. A Firm-Level Study with Theoretical and Methodological Reflections. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1167, Tampere University Press, Tampere. [A Doctoral Thesis] • O’Gorman, C. & Kautonen, M. (2004). Policies Promoting New Knowledge Intensive Ag- glomerations. -

Academic GNSS R&D and Curricula in the EU

Academic GNSS R&D and curricula in the EU Pieter De Smet, European Commission ICG-14, Bangalore, 8-13 November 2019 GNSS academic research and development in the European Union involves different universities and institutes across several countries. The universities and institutes cooperate with a number of objectives: – Bringing together providers of GNSS university education to facilitate the development of joint educational programmes; – Increasing co-operation between partners and industry and between national and European organisations like the European GNSS Agency, the European Commission and the European Space Agency; 2 – Identifying the needs of GNSS education and improving its process 2 and curricula; – Developing strategies for the current network of GNSS universities exploring new educational programmes and methods. Aalborg Universitet (Denmark) Aalborg University conducts research on the applications of GNSS in surveying and mapping. École Nationale de L'Aviation Civile (ENAC) (France) French Civil Aviation University’s research activities on navigation and positioning focus on such critical transport applications as aviation, road and rail. It encompasses GNSS integrity monitoring, receiver signal processing, multi-sensor navigation and precise positioning. 3 • Hochschule für Angewandte Wisenschaften München (Germany) Research at the Faculty of Geoinformatics at the Munich University of Applied Sciences comprises of UAV-Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing, Computer Vision, Navigation and Machine Learning. In particular, research is focused on object-based segmentation and classification for 3D Vegetation Mapping. • Institut supérieur de l’Aaéronautique et de l’Espace (ISAE) (France) GNSS education is part of the graduate and postgraduate programmes at ISAE’s Aerospace Electronics & Communications Programmes. Short courses are 4 organised for professional training. -

Bericht Zur ERASMUS Staff Training Week an Der Tampereen Yliopisto (Universität Tampere, Finnland)

Bericht zur ERASMUS Staff Training Week an der Tampereen Yliopisto (Universität Tampere, Finnland) - Mara Solka, Projektassistentin, Abteilung Forschung, Bereich Strategische Maßnahmen (ehem. Stabsstelle Zukunftskonzept) - Allgemeines Vom 27.05.2013 bis 31.05.2013 habe ich über das ERASMUS-Programm an einer Staff Training Week an der Universität Tampere in Finnland teilgenommen. Neben mir waren noch vier weitere Personen von deutschen Universitäten anwesend. Die restlichen 17 Teilnehmer kamen aus Ungarn, Frankreich, Litauen, UK, Spanien, Griechenland, Tschechien, den Niederlanden, der Türkei und Italien, aber auch aus Russland, China und Taiwan. Organisiert war der Aufenthalt vom International Office der Universität Tampere. Die Stadt Tampere Die Stadt Tampere liegt im Südwesten Finnlands zwischen den beiden Seen Näsijärvi und Pyhäjärvi und ist mit ca. 213.000 Einwohnern die drittgrößte Stadt im Land. Tampere ist stark industriell geprägt und wird daher häufig auch Manchester des Nordens genannt. Neben Schuhfabriken siedelten sich auch Papier- und Baumwollfabriken in der Stadt an. Mittlerweile sind jedoch viele Fabriken stillgelegt und in den umgebauten Backsteinfabrikhallen befinden sich mittlerweile Museen, Cafés und Kinos. Programm der Staff Training Week Wir Teilnehmer der Staff Training Week durchliefen die Woche über ein sehr gut organisiertes Programm, wobei jeder Teilnehmer vor der Ankunft entscheiden musste, welchem Track (Themen- schwerpunkt) er oder sie während der Woche folgen wollte. Zur Auswahl standen die folgenden Tracks: Curricula Planning and Student Services, International Services, Library Services. Ich habe mich für den Track International Services entschieden. Am ersten Tag gab es zunächst eine Begrüßung und kurze Einführung durch den Vizerektor der Universität und es folgten Präsentationen zum finnischen Bildungssystem im Allgemeinen, zu den neuesten Entwicklungen im finnischen Hochschulwesen und zur Universität Tampere im Speziellen.