Imagining a New Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the Opening of the Academic Year on 10 September 2019

1 Tampere University Speech by President Mari Walls at the opening of the academic year on 10 September 2019 Honoured guests, dear colleagues, alumni and friends of Tampere University. It is my great pleasure to welcome you all to celebrate the opening of our University’s first academic year! The idea to establish a unique new higher education community in Tampere can be traced back to more than five years ago when it was first formulated during discussions involving Kai Öistämö, Tero Ojanperä and Matti Höyssä, who presided over the Boards of the three Tampere- based higher education institutions, and then-Presidents of the institutions Kaija Holli, Markku Kivikoski and Markku Lahtinen. In spring 2014, the three institutions commissioned Stig Gustavson to identify areas where they could establish a leading international reputation and determine the necessary steps to achieve this vision. The 21 founding members signed the Charter of Tampere University Foundation on 20 April 2017. As set out in the Charter, the old, distinguished University of Tampere and Tampere University of Technology were to be merged to create a new university with the legal status of a foundation. The new university was also to become the majority shareholder of Tampere University of Applied Sciences. The agreement whereby the City of Tampere assigned its ownership of Tampere University of Applied Sciences Ltd to Tampere University Foundation was signed on 15 February 2018. Our new Tampere University started its operations at the beginning of this year. Today marks the 253rd day since the launch of the youngest university in Finland and in Europe. -

A Missionary Pictorial

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Stone-Campbell Books Stone-Campbell Resources 1964 A Missionary Pictorial Charles R. Brewer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Brewer, Charles R., "A Missionary Pictorial" (1964). Stone-Campbell Books. 286. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books/286 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Stone-Campbell Resources at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stone-Campbell Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. ( A MISSIONARYPICTORIAL Biographical sketches and pictures of men and women who have gone from the United States as members of churches of Christ to carry the gospel to other lands. TOGETHER WITH Articles and poems written for the purpose of stirring churches and individuals to greater activity in the effort to preach the gospel to "every creature under ( heaven." • EDITOR CHARLES R. BREWER • P UB LISHED BY WORLD VISION PUBLISHING COMPANY 1033 BELVIDERE DRIVE NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE 1964 ( Preface The divine char ge to take the word of the Lord to the whole world is laid upon all who wear the name of Christ, and God is ple ased with all who have a part, directly or indirectly in carry ing out th -:: great commission . But we feel th at in a special way his blessing descends on those who, forsaking th e ways of ga in and pleasure , give them selves wholly to th e preaching of the word. -

Rovaniemen Maakuntakaavaselostus

ROVANIEMEN MAAKUNTAKAAVA KAAVASELOSTUS Rovaniemen kaupunki Rovaniemen maalaiskunta Ranua LAPIN LIITTO ROVANIEMEN MAAKUNTAKAAVA SISÄLLYSLUETTELO 1. JOHDANTO 4 4.2.7. Lentoliikenteen alue (LL) 58 1.1. Maakuntakaavan tarkoitus 4 4.2.8. Vesiliikenteen alue (LV) 58 1.2. Laatimisorganisaatio 4 4.2.9. Yhdyskuntateknisen 1.3. Työn kulku ja hallinnollinen käsittely 5 huollon alue (ET) 58 1.4. Kaavoitusmenettely ja vuorovaikutus 4.2.10. Maankamaran ainesten- sekä kaavan ajallinen eteneminen 7 ottopaikka (EO) 58 4.2.11. Erityistoimintojen alue, 2. LÄHTÖKOHDAT 8 liikkuminen rajoitettua (ER) 58 2.1. Maakunnan kehittämisstrategia 8 4.2.12. Suojelualue (S) 59 2.2. Rovaniemen seutukunnan 4.2.13. Luonnonsuojelualue (SL) 59 nykytila ja ongelmat 12 4.2.14. Maa- ja metsätalous- 2.2.1. Taustatiedot 12 valtainen alue (M) 59 2.2.2. Kaavoitustilanne ja 4.2.15. Maa- ja metsätalousalue (MT) 59 maanomistus 23 4.2.16. Tiestö 59 2.2.3. Vahvuudet ja ongelmat 26 4.2.17. Rautatiet 60 2.3. Rovaniemen seutukunnan 4.2.18. Reitit 60 kehittämisstrategia 28 4.2.19. Muut 60 2.3.1. Tavoitteet 28 2.3.2. Aluerakenne 29 5. KAAVAN VAIKUTUSTEN ARVIOINTI 61 2.4. Rovaniemen seutukunnan 5.1. Yleistä 61 kestävä kehitys 29 5.2. Kaavan taloudelliset ja muut 2.4.1. Kestävä kehitys yhdyskunta- seuraamukset 61 rakenteen näkökulmasta 29 5.3. Vaikutukset maankäyttöluokittain 61 2.4.2. Kestävän kehityksen 5.3.1. Taajamatoiminnat ja kyläalueet 62 toteuttaminen 30 5.3.2. Virkistys 62 5.3.3. Loma-asunto- ja matkailu- 3. ALUEIDENKÄYTTÖSUUNNITELMA 32 palvelualueet 62 3.1. Yleisperiaatteet 32 5.3.4. Erityistoimintojen alueet 63 3.1.1. -

Vesientutkimuslaitoksen Julkaisuja Publications of the Water Research Institute

VESIENTUTKIMUSLAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS OF THE WATER RESEARCH INSTITUTE Matti Melanen & Risto Laukkanen: Quantity of storm runoff water in urban areas Tiivistelmä: Taajama-alueiden hulevesivalunnan määrä 3 Matti Melanen & Heikki Tähtelä: Particle deposition in urban areas Tiivistelmä: Taajama-alueiden ilmaperäinen laskeuma 40 Matti Melanen: Quality of runoff water in urban areas Tiivistelmä: Taajama-alueiden hulevesien laatu 123 VESIHALLITUS—NATIONAL BOARD OF WATERS, FINLAND Helsinki 1981 Tekijät ovat vastuussa julkaisun sisällöstä, eikä siihen voida vedota vesihallituksen virallisena kannanottona. The authors are responsible for the contents of the publication. It may not be referred to as the official view or policy of the National Board of Waters. ISBN 951-46-6066-8 SSN 0355-0982 Helsinki 1982. Valtion painatuskeskus 40 PARTICLE DEPOSITION IN URBAN AREAS Matti Melanen & Heikki Thte1ä MELANEN, M. & TÄHTELÄ, H. 1981. Particle deposition in urban areas. Publications of the Water Research Institute, National Board of “Waters, Finland, No. 42. In experiments carried out at seven urban test sites during 1977—1979, the average deposition rate compared to the one observed in regional background was roughly 100 % higher in respect to total organic carbon, 75 % higher in total phosphorus and the same in the cases of total nitrogen and chloride. In the case of calcium, the deposition rate was the same as the one in regional background in suburban catchments hut 100 % higher in city centres. The corresponding comparative figures for sulphate were 50 % in suburban catchments and 100—200 % in city centres. In suburban catchments, the pH of precipitation was on the average 0.4 units lower than the pH of precipitation in regional background. -

Leading a Fundamentally Detuned Choir: University of Tampere, Finland – a Civic University?

[Draft chapter – will be published in Goddard, J., Hazelkorn, E., Kempton, L. & Vallance, P. The Civic University: the Policy and Leadership Challenges. Edwar Elgar.] Markku Sotarauta Leading a Fundamentally Detuned Choir: University of Tampere, Finland – A Civic University? 1 Introduction A university is an academic ensemble of scholars who are specialised and deeply dedicated to a particular branch of study. Often scholars are passionate about what they do, and are willing to listen only to those people they respect, that is their colleagues and peers, but not necessarily heads of their departments, faculties or research centres. Despite many efforts, university leaders more often than not find it difficult to make academic ensembles sing the same song. If a group of singers perform together, it is indeed a choir. A community of scholars is not necessarily so. Singers agree on what to sing and how, they know their sheets, and a choir leader conducts them. A community of scholars, however, is engaged in a continuous search for knowledge through the process of thesis and antithesis, debates, as well as conflicts and fierce rivalry – without an overarching conductor. Universities indeed are different sorts of ensembles, as scholars may not agree about what is and is not important for a university as a whole. By definition a university is not a well-tuned chorus but a proudly and fundamentally detuned one. Leadership in, and of, this kind of organic entity is a challenge in itself, not to mention navigating the whole spectrum of existing and potential stakeholders. Cohen and March (1974) see universities as ‘organized anarchies’, as the faculty members’ personal ambitions and goals as well as fluid participation in decision- making suggest that universities are managed in decidedly non-hierarchical terms, but still within the structure of a formally organised hierarchy. -

Magnus Enckell's Early Work

Issue No. 1/2021 Tones of Black – Magnus Enckell’s Early Work Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff, PhD, Chief Curator, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, co-curator, ‘Magnus Enckell’ exhibition 2020–21 Also published in Hanne Selkokari (ed.), Magnus Enckell 1870−1925. Ateneum Publications Vol. 141. Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, 2020. Transl. Don McCracken Magnus Enckell may not be a household name but some of his works are very well known. Boy with Skull (1892) and The Awakening (1894) are paintings that have retained their fascination for generations in Finnish art history. But what was Enckell like, as a man and an artist? How did his career begin and how did it progress from the late 19th to the early 20th century? Enckell was already an influential person from a young age, and his interests and bold artistic experiments were the subject of much attention. His artistic career differed from others of his generation, not least because from the start, he received support from Finland’s most prominent artist, Albert Edelfelt, who also later served as his mentor, yet he was also very international in his artistic taste. When many of his fellow artists were involved with the transnational ideas of national revival, Enckell’s interests were focussed on international art and especially on Symbolism. Enckell’s life as an artist is intriguingly contradictory, and on a personal level he was apparently complex and often divided opinion.1 Yet he had many supporters, and he influenced ideas and perceptions about art among his close artist friends. Enckell was also good at networking and he forged his own international connections with artists in Paris. -

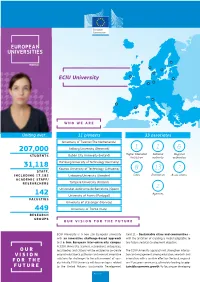

ECIU University

ECIU University WHO WE ARE Uniting over… 11 pioneers 33 associates University of Twente (The Netherlands) 1 1 6 207,000 Aalborg University (Denmark) Dublin City University (Ireland) Higher Education National Regional STUDENTS Institution authority authorities Hamburg University of Technology (Germany) 31,118 Kaunas University of Technology (Lithuania) 8 13 2 STAFF, INCLUDING 17,182 Linköping University (Sweden) Cities Enterprises Associations ACADEMIC STAFF/ Tampere University (Finland) RESEARCHERS 2 Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain) Agencies 142 University of Aveiro (Portugal) FACULTIES University of Stavanger (Norway) 449 University of Trento (Italy) RESEARCH GROUPS OUR VISION FOR THE FUTURE ECIU University is a new pan-European university Goal 11 – Sustainable cities and communities – with an innovative challenge-based approach with the ambition of creating a model adaptable to and a true European inter-university campus. any future societal development objective. At ECIU University, learners, researchers, enterprises, OUR local bodies and citizens will be enabled to co-create The ECIU University approach will strengthen interac- VISION original educational pathways and relevant innovative tion and engagement among education, research and solutions for challenges to the advancement of soci- innovation, with a positive effect on the local, regional FOR THE ety. Initially, ECIU University will focus on topics related and European community, ultimately leading to sus- FUTURE to the United Nations Sustainable Development tainable -

Symbolism of Surface and Depth in Edvard

MARJA LAHELMA want life and its terrible depths, its bottomless abyss. to hold on to the ideal, and the other that is at the same Lure of the Abyss: – Stanisław Przybyszewski1 time ripping it apart. This article reflects on this more general issue through Symbolist artists sought unity in the Romantic spirit analysis and discussion of a specific work of art, the paint- Symbolism of Ibut at the same time they were often painfully aware of the ing Vision (1892) by Edvard Munch. This unconventional impossibility of attaining it by means of a material work of self-portrait represents a distorted human head floating in art. Their aesthetic thinking has typically been associated water. Peacefully gliding above it is a white swan – a motif Surface and with an idealistic perspective that separates existence into that is laden with symbolism alluding to the mysteries of two levels: the world of appearances and the truly existing life and death, beauty, grace, truth, divinity, and poetry. The Depth in Edvard realm that is either beyond the visible world or completely swan clearly embodies something that is pure and beautiful separated from it. The most important aim of Symbolist art as opposed to the hideousness of the disintegrating head. would then be to establish a direct contact with the immate- The head separated from the body may be seen as a refer- Munch’s Vision rial and immutable realm of the spirit. However, in addition ence to a dualistic vision of man, and an attempt to separate to this idealistic tendency, the culture of the fin-de-siècle the immaterial part, the soul or the spirit, from the material (1892) also contained a disintegrating penchant which found body. -

All Clubs Missing Officers 2014-15.Pdf

Run Date: 12/17/2015 8:40:39AM Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing Club Officer for 2014-2015(Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) Undistricted Club Club Name Title (Missing) 27947 MALTA HOST Treasurer 27952 MONACO DOYEN Membershi 30809 NEW CALEDONIA NORTH Membershi 34968 SAN ESTEVAN Membershi 35917 BAHRAIN LC Membershi 35918 PORT VILA Membershi 35918 PORT VILA President 35918 PORT VILA Secretary 35918 PORT VILA Treasurer 41793 MANILA NEW SOCIETY Membershi 43038 MANILA MAYNILA LINGKOD BAYAN Membershi 43193 ST PAULS BAY Membershi 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA Membershi 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA President 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA Secretary 44697 ANDORRA DE VELLA Treasurer 47478 DUMBEA Membershi 53760 LIEPAJA Membershi 54276 BOURAIL LES ORCHIDEES Membershi 54276 BOURAIL LES ORCHIDEES President 54276 BOURAIL LES ORCHIDEES Secretary 54276 BOURAIL LES ORCHIDEES Treasurer 54912 ULAANBAATAR CENTRAL Membershi 55216 MDINA Membershi 55216 MDINA President 55216 MDINA Secretary 55216 MDINA Treasurer 56581 RIFFA Secretary OFF0021 © Copyright 2015, Lions Clubs International, All Rights Reserved. Page 1 of 1290 Run Date: 12/17/2015 8:40:39AM Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing Club Officer for 2014-2015(Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) Undistricted Club Club Name Title (Missing) 57293 RIGA RIGAS LIEPA Membershi 57293 RIGA RIGAS LIEPA President 57293 RIGA RIGAS LIEPA Secretary 57293 RIGA RIGAS LIEPA Treasurer 57378 MINSK CENTRAL Membershi 57378 MINSK CENTRAL President 57378 MINSK CENTRAL Secretary 57378 MINSK CENTRAL Treasurer 59850 DONETSK UNIVERSAL -

Tests of the Standard Model and Its Extensions in High-Energy E+ E

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS REPORT SERIES HU-SEFT R 1996-07 TESTS OF THE STANDARD MODEL AND ITS EXTENSIONS IN HIGH-ENERGY + e e− COLLISIONS arXiv:hep-ph/9603399v1 25 Mar 1996 RAIMO VUOPIONPERA¨ Research Institute for High Energy Physics University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland ISSN 0788-3587 UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS P.O.Box 9 FIN-00014 UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI FINLAND • • ISSN 0788-3587 Helsinki University Press 1996 Pikapaino RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS REPORT SERIES HU-SEFT R 1996-07 TESTS OF THE STANDARD MODEL AND ITS EXTENSIONS IN HIGH-ENERGY + e e− COLLISIONS RAIMO VUOPIONPERA¨ Research Institute for High Energy Physics University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Science of the University of Helsinki, for public criticism in Auditorium XIV on April 13th, 1996, at 10 o’clock. Helsinki 1996 ISBN 951-45-7356-0 ISSN 0788-3587 Helsinki University Press 1996 Preface This Thesis is based on research carried out at the Department of High Energy Physics of University of Helsinki, at the Research Institute for High Energy Physics (SEFT), at Conseil Europeen pour la Recherche Nucleaire (CERN), at the High Energy Physics Laboratory of the Department of Physics of the University of Helsinki, and at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY). The work has been supported by the Lapin rahasto of the Finnish Cultural Foundation and the Vilho, Yrj¨oand Kalle V¨ais¨al¨a Foundation. My stay at DESY was funded by the Province of Finnish Lapland, the City of Rovaniemi and the municipality of Rovaniemen maalaiskunta. -

Imaging the Spiritual Quest Spiritual the Imaging

WRITINGS FROM THE ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS 06 Imagingthe Spiritual Quest Imaging the Spiritual Quest Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality FRANK BRÜMMEL & GRANT WHITE, EDS. Imaging the Spiritual Quest Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality WRITINGS FROM THE ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS 06 Imaging the Spiritual Quest Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality FRANK BRÜMMEL & GRANT WHITE, EDS. Table of Contents Editors and Contributors 7 Acknowledgements 12 Imaging the Spiritual Quest Introduction 13 Explorations in Art, Religion and Spirituality. GRANT WHITE Writings from the Academy of Fine Arts (6). Breathing, Connecting: Art as a Practice of Life 19 Published by RIIKKA STEWEN The Academy of Fine Arts, Uniarts Helsinki The Full House and the Empty: On Two Sacral Spaces 33 Editors JYRKI SIUKONEN Frank Brümmel, Grant White In a Space between Spirituality and Religion: Graphic Design Art and Artists in These Times 41 Marjo Malin GRANT WHITE Printed by Mutual Reflections of Art and Religion 53 Grano Oy, Vaasa, 2018 JUHA-HEIKKI TIHINEN Use of Images in Eastern and Western Church Art 63 ISBN 978-952-7131-47-3 JOHAN BASTUBACKA ISBN 978-952-7131-48-0 pdf ISSN 2242-0142 Funerary Memorials and Cultures of Death in Finland 99 © The Academy of Fine Arts, Uniarts Helsinki and the authors LIISA LINDGREN Editors and Contributors Stowaway 119 PÄIVIKKI KALLIO On Prayer and Work: Thoughts from a Visit Editors to the Valamo Monastery in Ladoga 131 ELINA MERENMIES Frank Brümmel is an artist and university lecturer. In his ar- tistic practice Brümmel explores how words, texts and im- “Things the Mind Already Knows” ages carved onto stone semiotically develop meanings and and the Sound Observer 143 narratives. -

S34growth Kickoff Event 15-17 June 2016, Tampere, Finland

S34Growth kickoff event 15-17 June 2016, Tampere, Finland AGENDA Wednesday 15 June 2016 VENUE: Original Sokos Hotel Ilves, Sarka Cabinet, Hatanpään valtatie 1, 33100 Tampere Time Agenda 9:00 Project steering group meeting 10:15 Introduction to the OSDD Process Mr. James Coggs, Senior Executive, Strategy and Sectors - Appraisal and Evaluation, Scottish Enterprise Presentation of the baseline analysis Michael Johnsson, Senior EU Policy Officer, Skåne European Office 12:00 Lunch S34Growth kickoff seminar Moderator: Ms. Hannele Räikkönen, Director, Tampere Region EU Office 13:00 Opening Mr. Esa Halme, Region Mayor, Council of Tampere Region 13:10 Video greeting from the S34Growth financier Ms. Aleksandra Niechajowicz, Interreg Europe's Secretariat, Lille, France 1 13:20 Regional development and innovation policies in Tampere Region Mr. Jukka Alasentie, Director, Regional Development, Council of Tampere Region 13:40 Development of industrial value chains in Tampere Region Dr. Kari Koskinen, Professor, Head of Department, Mechanical Engineering and Industrial Systems, Tampere University of Technology 14:00 Experiences and opportunities of the Vanguard Initiative - New growth through smart specialisation Dr. Reijo Tuokko, Emeritus Professor, Mechanical Engineering and Industrial Systems,Tampere University of Technology 14:20 Coffee break 14:40 S34Growth - Enhancing policies through interregional cooperation: New industrial value chains for growth Mr. Esa Kokkonen, Director, The Baltic Institute of Finland, S34Growth Lead Partner 15:00 European