German and Scandinavian Protestantism, 1700-1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

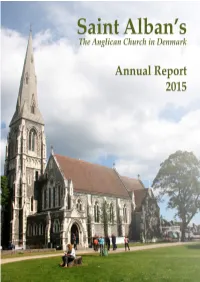

St Albans Annual Report 2015.Pdf

1" ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Contents:((1)(From(the(Chaplain,((1)(The(Chaplaincy(Council,((3)(Ministry(and(Mission(in(Jutland,((4)(Electoral(Roll,((4)(Chaplaincy( Council(Meetings(in(2015,((7)(Churchwardens’(Report,((8)(Registrar’s(Report,((8)(Altar(Guild,((8)(Mothers’(Union,((8)(Music(and( Choir,((9)(Coffee(Team,((10)(Ecumenical(Activities,((12)(Summer(Fête,((12)(The(Guardians’(Team,((12)(The(Sunday(School,((12)( Communications,((14)(Deanery(Synod,((15)(Diocesan(Synod.( ( ( FROM!THE!CHAPLAIN! ( Canon!Barbara!Moss,!who!served!as!Chaplain!in!the!Anglican!Church!in! Gothenburg!until!her!retirement!at!the!end!of!last!year,!used!to!say!that! one!of!the!questions!she!was!most!commonly!asked!by!members!of!the! local!Swedish!Church!was,!“How!many!people!work!at!your!Church?”! To!which!the!redoubtable!Barbara!would!reply,!“Most!of!them!”! ! What!is!true!for!Gothenburg!is!also!true!for!Copenhagen.!Our! extraordinary!Chaplaincy!covers!an!entire!country!(albeit!a!relatively! small!one!)!and!holds!regular!services!in!four!different!locations!(a!couple! of!hundred!miles!apart!).!And!yet,!it!thrives!with!just!one!fullNtime! employee!and!a!veritable!angelic!host!of!volunteers!who!give!of!their!time! and!their!talents!to!sustain!and!grow!Anglican!witness!in!Denmark.! ! ! As!this!Report!shows,!these!wonderful!people!were!especially!busy!in! 2015.!With!large!increases!in!numbers!attending!services,!an!expanding! electoral!roll!and!many!new!initiatives!being!undertaken,!we!have!more! -

Yngve Brilioth Svensk Medeltidsforskare Och Internationell Kyrkoledare STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXV

SIM SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF MISSION RESEARCH PUBLISHER OF THE SERIES STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA & MISSIO PUBLISHER OF THE PERIODICAL SWEDISH MISSIOLOGICAL THEMES (SMT) This publication is made available online by Swedish Institute of Mission Research at Uppsala University. Uppsala University Library produces hundreds of publications yearly. They are all published online and many books are also in stock. Please, visit the web site at www.ub.uu.se/actashop Yngve Brilioth Svensk medeltidsforskare och internationell kyrkoledare STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXV Carl F. Hallencreutz Yngve Brilioth Svensk medeltidsforskare och internationell kyrkoledare UTGIVENAV Katharina Hallencreutz UPPSALA 2002 Utgiven med forord av Katharina Hallencreutz Forsedd med engelsk sammanfattning av Bjorn Ryman Tryckt med bidrag fran Vilhelm Ekmans universitetsfond Kungl.Vitterhets Historie och Antivkvitetsakademien Samfundet Pro Fide et Christianismo "Yngve Brilioth i Uppsala domkyrkà', olja pa duk (245 x 171), utford 1952 av Eléna Michéew. Malningen ags av Stiftelsen for Âbo Akademi, placerad i Auditorium Teologicum. Foto: Ulrika Gragg ©Katharina Hallencreutz och Svenska lnstitutet for Missionsforskning ISSN 1404-9503 ISBN 91-85424-68-4 Cover design: Ord & Vetande, Uppsala Typesetting: Uppsala University, Editorial Office Printed in Sweden by Elanders Gotab, Stockholm 2002 Distributor: Svenska lnstitutet for Missionsforskning P.O. Box 1526,751 45 Uppsala Innehall Forkortningar . 9 Forord . 11 lnledning . 13 Tidigare Briliothforskning och min uppgift . 14 Mina forutsattningar . 17 Yngve Brilioths adressater . 18 Tillkommande material . 24 KAPITEL 1: Barndom och skolgang . 27 1 hjartat av Tjust. 27 Yngve Brilioths foraldrar. 28 Yngve Brilioths barndom och forsta skolar . 32 Fortsatt skolgang i Visby. 34 Den sextonarige Yngve Brilioths studentexamen. 36 KAPITEL 2: Student i Uppsala . -

The Nyhavn Experience

The Nyhavn Experience A non-representational perspective The deconstruction of the Nyhavn experience through hygge By Maria Sørup-Høj Aalborg University 2017 Tourism Master Thesis Supervisor: Martin Tranberg Jensen Submission date: 31 May 2017 Abstract This thesis sets out to challenge the existing way of doing tourism research by using a non- representational approach in looking into the tourist experience of Nyhavn, Denmark. The Nyhavn experience is deconstructed through the Danish phenomenon hygge, where it is being investigated how the contested space of Nyhavn with its many rationalities creates the frames, which hygge may unfold within. It is demonstrated how hygge is a multiple concept, which is constituted through various elements, including the audience, the actors and their actions, the weather, the sociality, the materiality and the political landscape in Nyhavn. The elements in the study are being discussed separately in order to give a better view on the different aspects. However, it is important to note point out that these aspects cannot be seen as merely individual aspects of establishing hygge, but that they are interrelated and interconnected in the creation of the atmosphere of hygge. The collecting of the data was done via embodied methods inspired by the performative turn in tourism, where the focus is on the embodied and multisensous experience. This is carried out by integrating pictures, video and audio clips, observant participation and impressionist tales in order to try to make the ephemeral phenomenon hygge as concrete as possible. Furthermore, data have been collected via netnography on TripAdvisor and travel blogs respectively. The study is characterized by being transdisciplinary, where theory has been drawn in from various fields, such as tourism, human geography, sociology, anthropology and sociology of the senses. -

Is Spoken Danish Less Intelligible Than Swedish? Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J

Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish? Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J. van Heuven, Renée van Bezooijen, Jos J.A. Pacilly To cite this version: Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J. van Heuven, Renée van Bezooijen, Jos J.A. Pacilly. Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish?. Speech Communication, Elsevier : North-Holland, 2010, 52 (11-12), pp.1022. 10.1016/j.specom.2010.06.005. hal-00698848 HAL Id: hal-00698848 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00698848 Submitted on 18 May 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish? Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J. van Heuven, Renée van Bezooijen, Jos J.A. Pacilly PII: S0167-6393(10)00109-3 DOI: 10.1016/j.specom.2010.06.005 Reference: SPECOM 1901 To appear in: Speech Communication Received Date: 3 August 2009 Revised Date: 31 May 2010 Accepted Date: 11 June 2010 Please cite this article as: Gooskens, C., van Heuven, V.J., van Bezooijen, R., Pacilly, J.J.A., Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish?, Speech Communication (2010), doi: 10.1016/j.specom.2010.06.005 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Lutheran Pastor

THE LUTHERAN PASTOR BY G. H. GERBERDING, D. D., PROFESSOR OF PRACTICAL THEOLOGY IN THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY OF THE EVAN GELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH, CHICAGO, ILL., AUTHOR OF N e w T e s t a m e n t “ ״ , T h e W a y o f S a l v a t io n i n t h e L u t h e r a n C h u r c h» . E t c ״ , C o n v e r s io n s SIXTH EDITION. PHILADELPHIA, PA.: LUTHERAN PUBLICATION SOCIETY. [Co p y r ig h t , 1902, b y G. H . G e r b e r d l n g .] DEDICATION, TO A HOLY MINISTRY, ORTHODOX AS CHEMNITZ, CALOVIUS, GERHARD, AND KRAUTH ; SPIRITUAL AND CONSECRATED AS ARNDT, SPENER, AND ZINZENDORF ; ACTIVE IN THE MASTER’S SERVICE AS FRANCKE, MUHLEN BERG, OBERLIN, AND PASSAVANT, THIS BOOK. IS HOPEFULLY DEDICATED. PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION. A SECOND edition of this work has been called for more speedily than we expected. For this we are grateful. It shows that there was a need for such a work, and that this need has been met. The book has been received with far greater favor, in all parts of our Church, than we had dared to hope. While there have been differences of opinion on certain points—which was to be expected— there have been no serious criticisms. This new edition is not a revision, but a reprint. In only two places has the text been corrected. On page 7 of the Introduction we have added a foot note, because the blunt statement of the text was liable to be misunderstood. -

Transcript of Spoken Word

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Interview with Paul Leeser Series Survivors of the Holocaust—Oral History Project of Dayton Ohio Holocaust Survivors in the Miami Valley Ohio. Wright State University in Conjunction with the Jewish Council of Dayton. Interviewer--Rabbi Cary Kozberg Date of Interviews: August 23, 1978 Q: This is Cary Kozberg speaking. I am conducting the first interview with Mr. Paul Leeser in my office at the Temple. Mr. Leeser lives in Richmond, Indiana. This is Wednesday afternoon, August 23, 1978. Mr. Leeser, how old are you? A: Fifty- seven. Q: Where were you born? A: In a city in the Rhineland (Germany) called, at that time, Hanborn(spelled by PL). Today it is a suburb of a larger city called Duisburg (Duisburg is again spelled by PL). It is called today: “Duisburg-Hanborn.” They are both in the Rhineland tare? Part of the German State of Westphalia. Q: Did you grow up there? A: My early years I spent in Hanborn. I went to school there. Then, when I was not quite in high school, that was in 1927 or 1928, we left the Rhineland and moved inland because my parents bought a business there. I continued my education in a little town called Rinteln which is on the Weser River near the town of Hameln in the district of Minden, at the time. The city, today is in the district of Hanover. I continued my grade school education there and had my first religious training. That is religious school and Hebrew school, etc. -

Professional & Academic 2017 CATALOG Reliable. Credible

Professional & Academic CELEBRATING CONCORDIA PUBLISHING HOUSE 2017 CATALOG Reliable. Credible. Uniquely Lutheran. CPH.ORG NEW RELEASES PAGE 4 PAGE 9 PAGE 15 PAGE 17 PAGE 21 PAGE 29 PAGE 11 PAGE 10 PAGE 18 2 VISIT CPH.ORG FOR MORE INFORMATION 1-800-325-3040 FEATURED REFORMATION TITLES PAGE 12 PAGE 12 PAGE 25 PAGE 25 PAGE 25 PAGE 25 PAGE 26 PAGE 33 PAGE 7 @CPHACADEMIC CPH.ORG/ACADEMICBLOG 3 Concordia Commentary Series Forthcoming 2017 HEBREWS John W. Kleinig 2 SAMUEL Andrew E. Steinmann New ROMANS 9–16 Dr. Michael P. Middendorf (cph.org/michaelmiddendorf) is Professor of eology at Concordia University Irvine, California. Romans conveys the timeless truths of the Gospel to all people of all times and places. at very fact explains the tremendous impact the letter has had ever since it was rst written. In this letter, Paul conveys the essence of the Christian faith in a universal manner that has been cherished by believers—and challenged by unbelievers—perhaps more so than any other biblical book. In this commentary, you’ll nd the following: • Clear exposition of the Law and Gospel theology in Paul’s most comprehensive epistle • Passage a er passage of bene cial insight for preachers and biblical teachers who desire to be faithful to the text • An in-depth overview of the context, ow of Paul’s argument, and commonly discussed issues in each passage • Detailed textual notes on the Greek, with a well-reasoned explanation of the apostle’s message “ e thorough, thoughtful, and careful interaction with other interpreters of Romans and contemporary literature that runs through the commentary is truly excellent. -

Det Historiske Hjørne V/ Jørgen Villadsen W2C3 Grønnegårds Havn

Det historiske hjørne v/ Jørgen Villadsen W2C3 Grønnegårds Havn. ”Christiansbro er den nye eksklusive del af Christianshavn, der ligger fra Knippelsbro og ned til Christianshavns kanal.” hedder det i Skanskas reklamemateriale for byggeriet Enhjørningen. Det materiale vi modtog ved den første information om byggeriet. Jeg vil i det følgende prøve at give en beskrivelse af området fra Arilds tid og til i dag, hvor det indrammes af Torvegade, Overgaden neden Vandet, Hammershøj Kaj og havnepromenaden langs kontorbygningerne. Oprindelig var området et lavvandet sumpet område mellem Amager og Sjælland, hvor sejlbare render lå over mod fiskerlejet Havn på Sjællands kyst. På nogle små øer byggede Absalon borg i 1167. Der hvor Christiansborg i dag ligger. Det ældste billedmateriale fra omkring 1580 og samtidige skriftlige kilder viser at forsyninger med fødevarer til København fra Amager foregik ved en primitiv færgefart mellem Revsholm på Amager og Københavns havn ved nuværende Højbro Plads. (Skovserkonens stade.) Københavns havn var på denne tid kun vandet mellem Slotsholmen og København. Nuværende Frederiksholms kanal og Gl. Strand. Der var dog et yderligere sejlløb i forlængelse af Gl. Strand, Bremerholm dyb. Det er fyldt op i dag og findes kun i gadenavnene, Dybensgade, Bremerholm og Holmens bro. I 1556 forærer Christian den III Københavns borgere Grønnegårds havn . Et område der svarer til grundene hvorpå Enhjørningen, Løven og Elefanten er placeret. Dengang var området først og fremmest vand omgivet af lidt sumpet land mod øst. Havnen blev brugt som vinterhavn for Københavns handelsskibe, der her kunne ligge i læ for vejr og vind, når de var lagt op for vinteren. -

Man As Witch Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic

Man as Witch Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic Series Editors: Jonathan Barry, Willem de Blécourt and Owen Davies Titles include: Edward Bever THE REALITIES OF WITCHCRAFT AND POPULAR MAGIC IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE Culture, Cognition and Everyday Life Julian Goodare, Lauren Martin and Joyce Miller WITCHCRAFT AND BELIEF IN EARLY MODERN SCOTLAND Jonathan Roper (editor) CHARMS, CHARMERS AND CHARMING Rolf Schulte MAN AS WITCH Male Witches in Central Europe Forthcoming: Johannes Dillinger MAGICAL TREASURE HUNTING IN EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA A History Soili-Maria Olli TALKING TO DEVILS AND ANGELS IN SCANDINAVIA, 1500–1800 Alison Rowlands WITCHCRAFT AND MASCULINITIES IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE Laura Stokes THE DEMONS OF URBAN REFORM The Rise of Witchcraft Prosecution, 1430–1530 Wanda Wyporska WITCHCRAFT IN EARLY MODERN POLAND, 1500–1800 Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic Series Standing Order ISBN 978–1403–99566–7 Hardback Series Standing Order ISBN 978–1403–99567–4 Paperback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and one of the ISBNs quoted above. Customer Services Department, Macmillan Distribution Ltd, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS, England. Man as Witch Male Witches in Central Europe Rolf Schulte Historian, University of Kiel, Germany Translated by Linda Froome-Döring © Rolf Schulte 2009 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2009 978-0-230-53702-6 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. -

Musical (And Other) Gems from the State Library in Dresden

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 23, Number 20, May 10, 1996 Reviews Musical (and other) gems from the State Libraryin Dresden by Nora Hamennan One might easily ask how anything could be left of what was scribe, and illuminations by a Gentile artist painted in Chris once the glorious collection of books and manuscripts which tian Gothic style. An analogous "cross-cultural" blend is were the Saxon Royal Library, and then after 1918, Saxon shown in two French-language illuminated manuscripts of State Library in Dresden. After all, Dresden was razed to the works by Boccaccio and Petrarca, respectively, two of the ground by the infamous Allied firebombing in 1945, which "three crowns" of Italian 14th-century vernacular literature, demolished the Frauenkirche and the "Japanese Palace" that produced in the 15th-century French royal courts. Then had housed the library's most precious holdings, as well as comes a printed book, with hand-painted illuminations, of taking an unspeakable and unnecessary toll in innocent hu 1496, The Performanceo/Music in Latin by Francesco Gaffu man lives. Then, the Soviets, during their occupation of the rius, the music theorist whose career at the Milan ducal court eastern zone of Germany, carried off hundreds of thousands overlapped the sojourns there of Josquin des Prez, the most of volumes, most of which have not yet been repatriated. renowned Renaissance composer, and Leonardo da Vinci, The question is partially answered in the exhibit, "Dres regarded by contemporaries as the finestimprovisational mu den: Treasures from the Saxon State Library," on view at the sician. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

Jeder Treu Auf Seinem Posten: German Catholics

JEDER TREU AUF SEINEM POSTEN: GERMAN CATHOLICS AND KULTURKAMPF PROTESTS by Jennifer Marie Wunn (Under the Direction of Laura Mason) ABSTRACT The Kulturkampf which erupted in the wake of Germany’s unification touched Catholics’ lives in multiple ways. Far more than just a power struggle between the Catholic Church and the new German state, the conflict became a true “struggle for culture” that reached into remote villages, affecting Catholic men, women, and children, regardless of their age, gender, or social standing, as the state arrested clerics and liberal, Protestant polemicists castigated Catholics as ignorant, anti-modern, effeminate minions of the clerical hierarchy. In response to this assault on their faith, most Catholics defended their Church and clerics; however, Catholic reactions to anti- clerical legislation were neither uniform nor clerically-controlled. Instead, Catholics’ Kulturkampf activism took many different forms, highlighting both individual Catholics’ personal agency in deciding if, when, and how to take part in the struggle as well as the diverse factors that motivated, shaped, and constrained their activism. Catholics resisted anti-clerical legislation in ways that reflected their personal lived experience; attending to the distinctions between men’s and women’s activism or those between older and younger Catholics’ participation highlights individuals’ different social and communal roles and the diverse ways in which they experienced and negotiated the dramatic transformations the new nation underwent in its first decade of existence. Investigating the patterns and distinctions in Catholics’ Kulturkampf activism illustrates how Catholics understood the Church-State conflict, making clear what various groups within the Catholic community felt was at stake in the struggle, as well as how external factors such as the hegemonic contemporary discourses surrounding gender roles, class status, age and social roles, the division of public and private, and the feminization of religion influenced their activism.