Selective Effects of Predation in a Tern Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Dwergstern3.Pdf

99 PRIMARY MOULT, BODY MASS AND MOULT MIGRATION OF LITTLE TERN STERNAALBIFRONS IN NE ITALY GIUSEPPE CHERUBINI, LORENZO SERRA & NICOLA BACCETTI Cherubini G., L. Serra & N. Baccetti 1996. Primary moult, body mass and moult migration of Little Tern Sterna albifrons in NE Italy. Ardea 84: 99 114. Large post-breeding gatherings of Little Terns Sterna albifrons are regu larly observed in the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Here, during five consecutive \ 1/ trapping seasons, 2956 birds were examined and ringed. Their breeding area, as indicated by 163 direct recoveries (mainly juveniles, ringed as chicks), spans over a broad sector of the Adriatic coasts, with colonies lo cated up to 133 km far. During their stay at the study area, adults undergo an almost complete moult. Two partial primary moult cycles can be ob \ served, the first of them being suspended when 2-4 outermost long primar ies have not yet been shed. Pre-migratory body mass build-up, enough for a ~/ flight longer than 1000 km, takes place during the very last days before de parture to the winter quarters, in most cases when the moult has reached a I suspended stage. Active primary moult and body mass increase do overlap in late moulting birds (after 27 August), indicating that the two processes are compatible, in case of time shortage. Post-breeding movements to the Lagoon of Venice seem to fit most requisites of moult migration. Key words: Sterna albifrons - Italy - biometrics - moult migration - ringing - fattening Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca' Fornacetta 9,1-40064 Oz zano Emilia BO, Italy. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

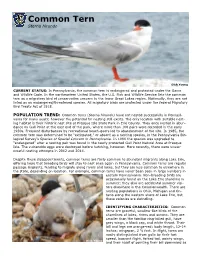

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo

Common Tern Sterna hirundo Dick Young CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the common tern is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. In the northeastern United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the common tern as a migratory bird of conservation concern in the lower Great Lakes region. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Common terns (Sterna hirundo) have not nested successfully in Pennsyl- vania for many years; however the potential for nesting still exists. The only location with suitable nest- ing habitat is their historic nest site at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County. They once nested in abun- dance on Gull Point at the east end of the park, where more than 100 pairs were recorded in the early 1930s. Frequent disturbances by recreational beach-goers led to abandonment of the site. In 1985, the common tern was determined to be “extirpated,” or absent as a nesting species, in the Pennsylvania Bio- logical Survey’s Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. In 1999 the species was upgraded to “endangered” after a nesting pair was found in the newly protected Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle. The vulnerable eggs were destroyed before hatching, however. More recently, there were unsuc- cessful nesting attempts in 2012 and 2014. Despite these disappointments, common terns are fairly common to abundant migrants along Lake Erie, offering hope that breeding birds will stay to nest once again in Pennsylvania. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

The Birds of Lido Beach

The Birds of Lido Beach An introduction to the birds which nest on and visit the beaches between Long Beach and Jones Inlet, with a special emphasis on the NYS endangered Piping Plover Paul Friedman Ver. 1.1 Best if viewed in full screen mode 1 Featured Birds Nest on the Beach Migrants* • Piping Plovers • Sanderlings • American Oystercatchers • Dunlins • Common Terns • Semipalmated Plovers • Least Terns • Black Skimmers * These three are just a few of the many migrants which use our beach as a layover 2 The Migrants Nest in the far north (Greenland , sub-arctic, etc.) – seen in Spring and mid/late Summer as they migrate to and from their nesting grounds Probe for food in the wet sand along the ocean’s edge • Sanderlings - most numerous of the three - can be seen in large groups in flight and running back and forth probing the wet sand left by a receding wave • Dunlins – characterized by long drooping bill – can be found with Sanderlings • Semipalmated Plovers– similar to Piping Plover in size and shape; and have distinctive black bands on the neck and forehead. Sanderlings Dunlins Semipalmated Plovers 3 Sanderlings Acrobatic, precision fliers; seen in large flocks. The entire flock can Note black legs and straight black bill turn on a dime; a required skill when evading a falcon. Large groups chase receding waves to…… … probe the wet sand for food 4 Dunlins Note droop in bill. Black belly is breeding plumage. Probing the wet sand for food Often found mixed in with Sanderlings At ocean’s edge 5 Semipalmated Plovers Note black forehead and black neck band Pictured here with its close cousin, the Piping Plover 6 Slurping a marine worm as one might a strand of spaghetti Taking flight The Lido Beach Nesting Birds o All nest in scrapes in sand between high tide and dunes o Two strategies – nest in colonies or nest in solitary pairs • Colonial Nesting Birds 1. -

A New Tern (Sterna) Breeding Record for Hawaii!

Pacific Science (1991), vol. 45, no. 4: 348-354 © 1991 by University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved A New Tern (Sterna) Breeding Record for Hawaii! SHEILA CONANT,2 ROGER CLAPP,3 LISA HIRUKI,4 AND BARRY CHOy 5 ABSTRACT: Recent observations of terns, either the Old World Little Tern (Sterna albifrons) or the New World Least Tern (Sterna antillarum), at Pearl and Hermes Reef in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands have documented that one of these species bred there in 1988 and possibly also in the several preceding years. Two small Sterna terns were first observed at Pearl and Hermes in 1984, and the numbers subsequently observed there gradually increased until fivebirds were recorded in 1988. In 1988 a nest containing three eggs was found , and at least one egg produced a nestling. No small Sterna terns were seen during a 2-week visit to the atoll in 1989 or a 2-day visit in 1990. No specimens were collected, and photographs taken do not permit specific identification of the birds. We favor S. albifrons sinensis because there are now specimen records of Asiatic Little Terns from French Frigate Shoals and Midway Atoll and a sight record from Laysan Island, and because a review of prevailing wind systems in the Pacific and other vagrant bird records from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands suggest that such birds are more likely to arrive from the west than from the east. EXAMINATION OF RECORDS of vagrants from Finch (Telespiza cantans) and the Hawaiian the Hawaiian Islands (Clapp, in litt.) suggests Monk Seal (Monachus schauinslandi), we also that birds from the Northwestern Hawaiian made incidental observations of seabirds and Islands, particularly the more westerly ones, shorebirds. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Black Tern Factsheet

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Black Tern Facts Identification Black terns are slender, graceful fliers with long pointed wings. They are often associated with coastal environments, but the black tern is found inland. During the breeding season this bird is relatively easy to identify because it is the only all black tern. In the fall, juveniles and molting adults have black and white mottled plumages. Flashing light under-wing linings make the black tern especially conspicuous in flight. © Marie Read Life History In early May, black terns begin their courtship displays at communal feeding and resting areas. Mating pairs are established by mid-May when they disperse to nesting areas in typically large “hemi-marshes”. Nest-site selection and nest-building are rapid, taking only four days. The shallow, cup-like nests are built upon floating materials of matted, dead marsh vegetation, old muskrat houses, cattail root stalks, emerging plants, algae, or fallen logs. Black terns have one brood of 2-4 eggs; both parents attend the nest and continually add nesting materials during the 21-day incubation period. Within two days of hatching, the chicks can swim, walk and run. They fledge in 21-24 days after hatching. Black terns inhabit freshwater marshes and lakes. They eat fish and insects, foraging by plucking prey from the water’s surface, and by capturing insects in flight. © Marie Read Range The black tern is a semi-colonial waterbird that nests on inland marshes, ponds, mouths of rivers and shores of large lakes. In the North America, their breeding range covers most of the northern states and into Canada. -

Late Triassic Dinosaur Tracks Reinterpreted at Gettysburg National Military Park

LATE TRIASSIC DINOSAUR TRACKS REINTERPRETED AT GETTYSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK BY VINCENT L. SANTUCCI AND ADRIAN P. H UNT fossil tracks has advanced signifi- ONG BEFORE THE FOOTSTEPS OF UNION cantly over the past two decades and confederate soldiers traversed and we are now able to offer a Lsouth-central Pennsylvania, early di- different interpretation of the nosaurs left their footprints in ancient mud. Gettysburg tracks. The fossil Fossilized tracks preserve evidence that di- tracks represent the ichnogenus nosaurs existed in the Gettysburg area over Atreipus which was first de- 200 million years ago during a time period scribed by Olsen and Baird in called the Triassic. The tracks also illustrate 1986. The tracks can be further another example of a NPS unit, primarily identified to the ichnospecies A. focused on cultural resources, that must face mil-fordensis. the challenges of managing and interpret- Atreipus milfordensis repre- ing paleontological resources. sents, as of yet, an undescribed The dinosaur tracks are preserved in dinosaur that exhibits a thero- blocks of mudstone that were quarried from podlike pes (foot) in combina- Figure 1. Fossil manus and pes tracks of Atreipus an area outside park boundaries. However, tion with a short-clawed and milfordensis from atop a stone bridge at Gettysburg the quarried blocks were transported to the functionally tridactyl (three- National Military Park, Pennsylvania. park and used in the construction of stone toed) manus (hand). The track bridges during the 1930s. In 1937, over 50 pattern indicates that this dinosaur habitu- Additionally, as with the Gettysburg fos- additional tracks were discovered in blocks ally used all four limbs in locomotion. -

Caribbean Roseate Tern and North Atlantic Roseate Tern (Sterna Dougallii Dougallii)

Caribbean Roseate Tern and North Atlantic Roseate Tern (Sterna dougallii dougallii) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photo Jorge E. Saliva U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Caribbean Ecological Services Field Office Boquerón, Puerto Rico Northeast Region New England Field Office Concord, New Hampshire September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Reviewers............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Methodology........................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Background............................................................................................................. 2 1.3.1 FR Notice………………………………………………………………… 2 1.3.2 Listing history……………………………………………...…………….. 2 1.3.3 Associated rulemakings………………………………………………….. 3 1.3.4 Review history…………………………………………………………… 3 1.3.5 Recovery Priority Number………………………………………….……. 3 1.3.6 Recovery plans…………………………………………………………… 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment policy................................ 3 2.1.1 Is the species under review a vertebrate?................................................... 4 2.1.2 Is the DPS policy applicable?..................................................................... 4 ENDANGERED NORTHEAST POPULATION 2.2 Recovery Criteria..................................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Does the species have a