Of 17 Mega Engineering Projects and Archeological Discovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

80 Otobüs Zaman Çizelgesi Ve Hat Güzergah Haritası

80 otobüs saatleri ve hat haritası 80 Kazlıçeşme/yedık̇ ule - Emınönü̇ Web Sitesi Modunda Görüntüle 80 otobüs hattı (Kazlıçeşme/yedık̇ ule - Emınönü)̇ arası 3 güzergah içeriyor. Hafta içi günlerde çalışma saatleri: (1) Eminönü →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray: 07:25 - 18:50 (2) Eminönü Transit →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray: 19:25 (3) Kazlıçeşme Marmaray →Eminönü: 06:55 - 17:23 Size en yakın 80 otobüs durağınıbulmak ve sonraki 80 otobüs varış saatini öğrenmek için Moovit Uygulamasını kullanın. Varış yeri: Eminönü →Kazlıçeşme 80 otobüs Saatleri Marmaray Eminönü →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray Güzergahı 18 durak Saatleri: HAT SAATLERİNİ GÖRÜNTÜLE Pazartesi 07:25 - 18:50 Salı 07:25 - 18:50 Eminönü Çarşamba 07:25 - 18:50 Haliç Metro Ragip Gümüşpala Caddesi Perşembe 07:25 - 18:50 Cuma 07:25 - 18:50 Unkapanı / Aksaray Yönü Cumartesi Çalışmıyor Vefa / Aksaray Yönü Pazar Çalışmıyor İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Atatürk Boulevard, Turkey 80 otobüs Bilgi Yusufpaşa / Topkapı Yönü Yön: Eminönü →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray Tanburi Cemilbey Sokak, Turkey Duraklar: 18 Yolculuk Süresi: 27 dk Haseki Hat Özeti: Eminönü, Haliç Metro, Unkapanı / Aksaray Yönü, Vefa / Aksaray Yönü, İstanbul İNebey Büyükşehir Belediyesi, Pertevniyal Valide Çakırağa Cami Aralığı, Turkey Sultan, Yusufpaşa / Topkapı Yönü, Haseki, İNebey, Langa / Yedıkule Yönü, Davutpaşa / Langa / Yedıkule Yönü Yedıkule Yönü, İstanbul Hastanesi, Ağahamamı / Yedıkule Yönü, Gençosman / Yedıkule Yönü, Davutpaşa / Yedıkule Yönü Merhaba / Yedıkule Yönü, İMrahor, Borsa İstanbul Zeytinburnu Anadolu Lisesi, Horasancı -

80T Otobüs Zaman Çizelgesi Ve Hat Güzergah Haritası

80T otobüs saatleri ve hat haritası 80T Kazlıçeşme/yedık̇ ule - Taksıṁ Web Sitesi Modunda Görüntüle 80T otobüs hattı (Kazlıçeşme/yedık̇ ule - Taksım)̇ arası 3 güzergah içeriyor. Hafta içi günlerde çalışma saatleri: (1) Kazlıçeşme Marmaray →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray: 06:00 - 21:20 (2) Kazlıçeşme Marmaray →Taksim Tünel: 19:00 - 20:20 (3) Taksim Tünel →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray: 19:30 - 22:20 Size en yakın 80T otobüs durağınıbulmak ve sonraki 80T otobüs varış saatini öğrenmek için Moovit Uygulamasını kullanın. Varış yeri: Kazlıçeşme 80T otobüs Saatleri Marmaray →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray Kazlıçeşme Marmaray →Kazlıçeşme Marmaray 41 durak Güzergahı Saatleri: HAT SAATLERİNİ GÖRÜNTÜLE Pazartesi 06:00 - 21:20 Salı 06:00 - 21:20 Kazlıçeşme Marmaray Çarşamba 06:00 - 21:20 Yedikule Cami Sokak, Turkey Perşembe 06:00 - 21:20 Cuma 06:00 - 21:20 İMrahor Cumartesi 06:00 - 21:20 Merhaba / Aksaray Yönü Pazar 06:20 - 21:20 Gençosman / Aksaray Yönü Tütünlük Sokak, Turkey Ağahamamı / Aksaray Yönü Kehribar Sokak, Turkey 80T otobüs Bilgi Yön: Kazlıçeşme Marmaray →Kazlıçeşme İstanbul Hastanesi Marmaray Duraklar: 41 Davutpaşa / Aksaray Yönü Yolculuk Süresi: 61 dk Horasancı Hasan Çık., Turkey Hat Özeti: Kazlıçeşme Marmaray, Yedikule, İMrahor, Merhaba / Aksaray Yönü, Gençosman Langa / Aksaray Yönü / Aksaray Yönü, Ağahamamı / Aksaray Yönü, İstanbul Hastanesi, Davutpaşa / Aksaray Yönü, İNebey Langa / Aksaray Yönü, İNebey, Pertevniyal Çakırağa Cami Sokak, Turkey Valide Sultan, İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi, Vefa / Taksim Yönü, Unkapanı / Taksım Yönü, Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Şişhane2, -

Chapter 3 Road Network and Traffic Volume

The Study on Integrated Urban Transportation Master Plan for Istanbul Metropolitan Area in the Republic of Turkey Final Report Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Road Network and Traffic Volume 3.1 Road Network 3.1.1 Inter-regional Road Network 1) Existing Road Turkey is situated at the transit corridor between South-east Europe and the Middle East. Since “The Declaration for The Construction of International Arteries” (AGR) prepared by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN/ECE) in 1950 in Geneva, Turkey has developed international corridors connecting it to Southern Europe, because the international road network of AGR included an extension to Turkey. According to the provisions of AGR, two arteries should reach Turkey as E-Road. These are E-80 entering from the Bulgarian border (Kapikule) and E-90 entering from the Greek border (Ipsala). These two main routes link the International Road Network of Europe with the Middle East and Asia at southern and eastern borders of Turkey via Anatolia. Source: KGM, Ministry of Transportation Figure 3.1.1 International Road Network through Turkey, 2007 In addition to the E-Roads, the Trans-European Motorway (TEM) project is ongoing and it covers the whole country as an expressway network. The TEM highway network in Turkey starts from Edirne at the Bulgarian border and passes through Istanbul via the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge and parts into two branches in Ankara going eastward and southward. Its eastern branch again parts into two branches in Askale. One of them reaches Trabzon in the Black Sea Region, and the other ends in Gurbulak at the Iranian border. -

Republic of Turkey Traffic Demand Management of Historical Area in Istanbul (İSTDM)

( Traffic Demand Management of Historical Area in Istanbul Republic of Turkey İ STDM) Republic of Turkey Transport Department of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Republic of Turkey Traffic Demand Management of Historical Area in Istanbul (İSTDM) Final Report Final Report Vol.2 Vol.2 July, 2014 July, 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) ALMEC Corporation PADECO Co., Ltd. EI JR 14-139 ( Traffic Demand Management of Historical Area in Istanbul Republic of Turkey İ STDM) Republic of Turkey Transport Department of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Republic of Turkey Traffic Demand Management of Historical Area in Istanbul (İSTDM) Final Report Final Report Vol.2 Vol.2 July, 2014 July, 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) ALMEC Corporation PADECO Co., Ltd. The exchange rate used in the report is: US$ 1 = TRY 1.90 Table of Contents 1. Characteristics of the Study Area 1.1 Socio-economic Characteristics .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Land Use Conditions ........................................................................................................................... 1-4 1.3 Transport Infrastructure and Facilities ................................................................................................. 1-5 1.4 Transport Projects ............................................................................................................................... 1-9 2. Transport Demand Changes by Rail-Transit Development 2.1 -

Istanbul Ulasim

Istanbul Ulasim Company Presentation January, 2014 1 Istanbul City Istanbul Ulasim Activities Railway Projects in Istanbul 2 Istanbul City 3 Istanbul 5.343km 2 Area Strategic Location Demography & History Along the historical Silk Route Population of 13.8 million, Total area: 5.343 km 2 Trans-continental city A history of 8.500 years The city from north to south: 45 km, east to west: 165 km 4 Transportation Statistics 13.8 27 600 1.1 Million Million New vehicles Million Population Daily trips Added to the roads Daily trips between everyday continents 5 Transportation Statistics 2.5 1.8 25.000 49 MIN. 133 Million Million km Average Cars per Vehicles Vehicles Network Trip Time 1000 residents on the Road Everyday 6 Transportation Modes T. Modes Road System 83.7 % Rail System 13 % Waterborne 3.3 % Private Cars Istanbul Ulasim (tram, Sehir Hatlari (public operator) Buses subway) Private Boats Privately-owned public TCDD (commuter line) buses IETT (Tunnel, heritage Private Buses tram) Minibuses, Taxis 7 Governance of PT Istanbul Lord Mayor Secretary-General Deputy Secretary-General (Transportation) Railway Systems Transportation Department Department Railway Systems Railway Systems Transportation Planning Traffic Division (European) Division (Asian) Division Division Public Transportation Transportation Division Coord. Division Affiliates Mega Projects in Istanbul Marmaray The Eurasia Tunnel The 3 rd B. Bridge The 3 rd Airport The Istanbul Canal Bosporus Strait Bosporus Road Crossing The artificial sea-level 8 Lanes of motorway 150 million passenger Rail Transit Project Project waterway 2 Rail Lines Operation rights for 25 Overall Length 76 km 14.6-km route including Connects the Black 2012-2015 years Tunnel 13.6 km a 5.4-km twin-deck Sea to the Marmara € 22 billion pphpd 75.000 tunnel Sea $ 2.5 -3 billion BOT -$ 1.3 billion ~$10 billion 9 Istanbul Ulasim 10 Istanbul Ulasim Products and Services Operational Maintenance Engineering & Rolling Stock Turnkey Services Services Consulting Design and Electromec. -

İstanbul'a İlçe İlçe, Mahalle Mahalle Metro

İstanbulBülteniBu bülten sizindir, alabilirsiniz • www.ibb.gov.tr • Ocak 2014 İstanbul’a İlçe İlçe, Mahalle Mahalle Metro Sevgili İstanbullular Göreve geldiğimiz günden itibaren daha hızlı, daha konforlu ve daha güvenli toplu ulaşım imkanına kavuşmanız için 365 gün 24 saat prensibiyle dur durak bilmeden çalışıyoruz. Geride bıraktığımız 10 yılda dev ulaşım yatırımlarının altına imza attık. İstanbul’u ilçe ilçe, mahalle mahalle metroya kavuşturma hedefiyle raylı sistem yatırımlarımıza hız ve öncelik verdik. Şehrin pek çok noktasında yerin altında gece gündüz devam eden çalışmalarımız, emin adımlarla ilerliyor. İstanbul, New York’tan sonra dünyanın ikinci büyük metro ağına sahip kenti olma yolunda hızla ilerliyor! Siz değerli hemşehrilerimizin yaşam standartlarını yükseltmek için 39 ilçemizde ulaşımdan altyapıya, çevreden kültür-sanata, eğitimden spora, bilgi teknolojilerinden itfaiye hizmetlerine kadar tüm sektörlerde yatırım yapmaya ve hizmet üretmeye devam ediyoruz. Çünkü biliyoruz ki; medeniyetlerin çeyiz sandığı konumundaki İstanbul ve siz değerli İstanbullular her şeyin en güzeline ve en iyisine layıksınız. Şahsım ve ekibim, İstanbul’umuzu kültür, sanat, turizm, spor ve kongreler şehri yapmak için dur durak bilmeden çalışıyoruz. Bu anlayıştan hareketle kentimize bir büyük yatırımı daha kazandırmak için çalışmalarımıza başladık. Dev bir yatırım olarak hayata geçireceğimiz “fuar” ve “kongre kampüsü” projesi ile İstanbul, dünyada örneği olmayan bir etkinlik alanına kavuşacak. Bu dev yatırım, diğer dünya şehirleriyle yarış içinde olan İstanbul’u -

Sustainable Urban Mobility: the Example of Istanbul

Division 44 Water, Energy, Transport Sustainable Urban Mobility: The Example of Istanbul A Short Survey Case Studies in Sustainable Urban Transport #3 About the author Maik Hennig (44) is an Industrial Engineer graduated from universities of applied science in Kiel and Stuttgart (Germany). He has been engaged in implementing railroad projects and infrastructure investments in Europe and Africa since more than 15 years. Currently working as expert to the Turkish Ministry of Transportation on behalf of German Techni- cal Cooperation (GIZ) and European Invest- ment Bank (EIB) his fields of activities are technical feasibility and compatibility in the rail and transport sectors, societal mobility, common benefit of public transport and sus- tainability of related services and facilities. Acknowledgement Special thanks go to our expert reviewer Sibel Bulay (EMBARQ) for review and valuable comments. All remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. Sustainable Urban Mobility: The Example of Istanbul A Short Survey Case Studies in Sustainable Urban Transport #3 Disclaimer Findings, interpretation and conclusions expressed in this document are based on the information gained by the author and from the contributors. GIZ does not guarantee the accuracy or com- pleteness of information in this document and cannot be held responsible for any errors, omissions or losses, which emerge from its use. IMPRINT Author: Maik Hennig Editor: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH P. O. Box 5180 65726 Eschborn, Germany http://www.giz.de Division 44 – Water, Energy, Transport Sector Project "Transport Policy Advisory Services" On behalf of Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Division 313 – Water, Energy, Urban Development P. -

Kent İçi Raylı Toplu Taşıma Sistemleri İncelemesi Ve Dünya Örnekleri İle

i ULAŞTIRMA, DENİZCİLİK VE HABERLEŞME BAKANLIĞI KENT İÇİ RAYLI TOPLU TAŞIMA SİSTEMLERİ İNCELEMESİ VE DÜNYA ÖRNEKLERİ İLE KARŞILAŞTIRILMASI Göktuğ BAŞTÜRK Ulaştırma ve Haberleşme Uzmanlığı Tezi Eylül 2014 Ankara ii iii ULAŞTIRMA, DENİZCİLİK VE HABERLEŞME BAKANLIĞI KENT İÇİ RAYLI TOPLU TAŞIMA SİSTEMLERİ İNCELEMESİ VE DÜNYA ÖRNEKLERİ İLE KARŞILAŞTIRILMASI Göktuğ BAŞTÜRK Ulaştırma ve Haberleşme Uzmanlığı Tezi Eylül 2014 Ankara i KABUL VE ONAY Göktuğ BAŞTÜRK tarafından hazırlanan Kent İçi Raylı Toplu Taşıma Sistemleri İncelemesi ve Dünya Örnekleri ile Karşılaştırılması adlı bu tezin Ulaştırma ve Haberleşme Uzmanlığı tezi olarak uygun olduğunu onaylarım. Genel Müdür Yardımcısı Yalçın EYİGÜN Tez Danışmanı Bu çalışma, tez savunma komisyonumuz tarafından Ulaştırma ve Haberleşme Uzmanlığı Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir. Adı ve Soyadı İmzası Başkan : Üye : Üye : Üye : Üye : Bu tez, Ulaştırma, Denizcilik ve Haberleşme Bakanlığı tez yazım kurallarına uygundur. ii İÇİNDEKİLER KABUL VE ONAY ...................................................................................................... i İÇİNDEKİLER ............................................................................................................ ii ÖZET............................................................................................................................ v ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ vi TEŞEKKÜR .............................................................................................................. -

Aksaray Atatürk Havalimanı Metro Hattı

Aksaray Emniyet-Fatih Topkapý-Ulubatlý Bilgi ve Danýþma için Ýþletmeci Kurum: Bayrampaþa-Maltepe Ýstanbul Ulaþým San. ve Tic. A.Þ. Aksaray 444 00 88 Saðmalcýlar [email protected] Atatürk Havalimaný Kartaltepe-Kocatepe Metro Hattý Esenler Otogar Coach Station Terazidere Davutpaþa-Y. T. Ü. Ýþletme Saatleri ve Sefer Sýklýðý Merter (Aksaray - Atatürk Havalimaný) Zeytinburnu 06.00 - 07.00 8 dakika Bakýrköy-Ýncirli 07.00 - 09.00 4,5 dakika 09.00 - 16.00 6 dakika Bahçelievler 16.00 - 16.00 6 dakika Ataköy-Þirinevler 16.00 - 20.00 5 dakika 20.00 - 22.00 7,5 dakika Yenibosna 22.00 - 00.00 10 dakika D. T. M.-Ýstanbul Fuar Merkezi World Trade Center-Ýstanbul Fair Center Atatürk Havalimaný www.ulasimturkiye.com Toplu Taþýmacýlýk forum sitesi tarafýndan, Atatürk Airport ücretsiz olarak daðýtýlmak ve kullanýlmak üzere hazýrlanmýþtýr. Bilgiler iþletmeci web sitesinden derlenmiþtir. Metrobüs aktarmasý, 34 Avcýlar-Zincirlikuyu ve 34T Avcýlar-Topkapý hatlarýna tüm Tasarým : Esat Tanören gün 34G Avcýlar-Söðütlüçeþme hattýna pik saatlerde mümkündür. Metrobüs çalýþma Redaktör : Baþar Alabay saatleri için www.iett.gov.tr adresinde arama yapýnýz. HA RAMÝ Okmeydaný MAHMUTBEY KARTALTEPE KOCATEPE Hat þemasý iþaretlemeleri / Pictogram Series PÝERRE LOTÝ TOPÇULAR Aksaray - Atatürk Havalimaný metro hattý 3 Eylül 1989 da Ýstanbulun OTOGAR Halýcýoðlu KÝRAZLI KUZEY EYÜP SAÐMALCILAR DEMÝRKAPI ilk metro hattý olarak Aksaray ve Kartaltepe istasyonlarý arasýnda MENDERES Ayvansaray ÞEHÝTLÝK ESENLER GA Aksaray-Atatürk Havalimaný metro hattý / Metro line BAÐCILAR BAYRAMPAÞA - MALTEPE Edirnekapý ODA TERAZÝDERE EDÝRNEKAPI iþletmeye açýlmýþtýr. Ýkinci etapta önce Zeytinburnu, daha sonra ise BAÐCILAR Adnan Menderes Blv. TÜNEL VATAN ÞÝÞHANE KÝRAZLI GÜNEY Bayrampaþa - Maltepe GÜNEÞTEPE ÇÝNÇÝN - ÜÇYÜZLÜ Baðcýlar-Kabataþ tramvay hattý / Tram line Ataköy-Þirinevlere uzatýlan hat 20 Aralýk 2000 tarihinde Atatürk TOPKAPI - ULUBATLI Topkapý YAVUZ SELÝM UNKAPANI DAVUTPAÞA FETÝH KAPI Cevizlibað EMNÝYET - FATÝH TOPKAPI Havalimanýna baðlanmýþtýr. -

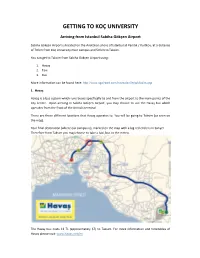

Getting to Koç University

GETTING TO KOÇ UNIVERSITY Arriving from Istanbul Sabiha Gökçen Airport Sabiha Gökçen Airport is located on the Anatolian shore of Istanbul at Pendik / Kurtkoy, at a distance of 70 km from Koç University main campus and 50 km to Taksim. You can get to Taksim from Sabiha Gökçen Airport using: 1. Havaş 2. Taxi 3. Bus More information can be found here: http://www.sgairport.com/havaalani/eng/ulasim.asp 1. Havaş Havaş is a bus system which runs buses specifically to and from the airport to the main points of the city center. Upon arriving in Sabiha Gökçen Airport, you may choose to use the Havaş bus which operates from the front of the Arrivals terminal. There are three different locations that Havaş operates to. You will be going to Taksim (as seen on the map). Your final destination (where our campus is), marked on the map with a big red circle is in Sarıyer. Therefore from Taksim you may choose to take a taxi, bus or the metro. The Havaş bus costs 13 TL (approximately $7) to Taksim. For more information and timetables of Havaş please visit: www.havas.net/en 2. Taxi From Sabiha Gökçen you can also use private taxis. Taxi's are available outside the terminal. Then it can be rather expensive if you intend travelling all the way to central Đstanbul. Cars are available on request. (Phone number: +90 216 588 00 35-36) 3. Bus A public bus operates from Sabiha Gökçen Airport in front of the Arrivals section which takes you to 4. -

109 Yıldan Beri İstanbul Metrosuna Proje Hazırlanıyor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Sahihi: ( 'umhtıriyel Matbaacılık ve Cia/cıccilik Turk Anonim Şirketi adına Servis Şefleri. İstanbul Haberleri: Relıa O /, Dış Haberler: Krguıı Balcı, Ivkonomi: Os Hasıın ve Yavan: Cumhuriyet Matbaacılık veCa/eiecilikbrought T A Ş. to Türkyou by Ocağı CORE Cad. 19/41 Cağaloğlu Istanbul, PK: 246-lslanbul, Tel: 526 10 00 (9 hal). Telex: 22246 • Nadir Nadi, # Genci Yayın Müdürü: lla sjııı C emal, Müessese Müdürü: İlm i man l Hanay, Kültür: Aydın Kmey, Maga/in: Yalçın IVk^eıı, Spor Danışmanı: Abdııl- provided by Istanbul Sehir University Repository ne l'>akli|>il. Ya/ı İşleri Müdürü: Oka> ( .oııensiıı, # Haber Merke/i Mu kudir Yucelrnan, Du/eltme: Refik Durlms, Anıştırma; Şahin Alpay, İş Sendika: Şükran Hurolur: Ankara: Ziya Gokalp Bulvarı İnkılap Sokak No: 19/4 Tel: 33 II 41-47, duru: Yıılyın Baser, Savla Du/cni Yönelmeni: A li Acar, • Temsilciler: AN Kelemi. # Koordinatör: Ahmel Kurulsan, # Mali İşler: Knıl Krkul, İlan: /iy a Krge- l'clex: 42344 • I/m ir: H alil Ziya Bulvarı No: 64/3, Tel: 25 47 09-13 12 30 Telex: Cumhuriyet K AR A Yalçın I İngini,İZM İR : Hikmet (,'eliııkaya. AD AN A: Metımel Mercan. ııe. Halkla İlişkiler: (dılderen Koşar, İdare: Hüseyin (¿ürer, Işlclme: Şadım Sönme/. 52359 • Adana: Çakmak Cad. No: 134 Kal 3, Tel: 14550-19731 Telex; 62155. __________________ 11______i- TAKVİM 15 Şubat 1985 İmsak: 5.26 Güneş: 6,52 öğle: 12.23 İkindi: 16.15 Akşam; 17.44 Yalsı: 19,04 YIL 1973—/amanın İstanbul Belediye Başkam, metro Belediye planlanın hükümetin onayım Başkam Fahri almak üıere Ankora ya götürdü A labey, 109 yıldan beri İstanbul Fahri Atabey, projenin gerçekleşmesi için İstanbullulara 60 milyon doların kanı olduğunu söyledi metro müjdesi veriyor: “Proje için 60 milyon İstanbul Metrosu rnun dolar hazır, temel metrosuna proje hazırlanıyor Cumhuriyet teme i Cumhuriyet Bayramı 'nda atılacak.. -

Istanbul Ulaşim A.Ş

İSTANBUL ULAŞIM A.Ş. ŞİRKET ÜNVANI : İstanbul Ulaşım San. ve Tic. A.Ş. GENEL MÜDÜR : Ömer YILDIZ ŞİRKET ADRESİ : Ferhatpaşa Metro Tesisleri 34220 Esenler / İSTANBUL TELEFON : (0212) 568 99 70 FAKS: (0212) 568 89 00 WEB : www.istanbululasim.com E-POSTA : [email protected] YOLCU HİZMETLERİ MERKEZİ : 444 00 88 İstanbul’un, en önemli gereksinimlerinden biri olan “kent içi toplu ulaşım” konusunda geliştirdiği çözümler, bundan yaklaşık 150 sene önce, Dersaadet Tramvay Şirketi’nin şehre sağladığı raylı sistemlerle başlamıştır. 1869 yılında hizmete giren atlı tramvaylar, 1912’ye kadar İstanbul halkına hizmet vermiş, bu tarihten sonra elektrikli sistemlere geçilmiş ve 1966 yılına kadar kent içi toplu ulaşım ağırlıklı olarak elektrikli tramvaylarla sağlanmıştır. 1960’lı yılların başından itibaren hızla göç alan ve büyüyen İstanbul’da toplu taşımacılık akaryakıtlı ve lastikli araçlara bırakılmıştır. Ancak, karayolu taşımacılığının büyüyen ve kalabalıklaşan şehre yetmemeye başlaması ile birlikte en işlevsel çözüm olarak yeniden “raylı sistemlere dönüş” programları yapılmaya başlanmış ve İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi tarafından raylı sistemlerin yapımına 1985 yılında tekrar başlanmıştır. İstanbul Ulaşım A.Ş., yapımı tamamlanan raylı sistem hatlarının işletmeciliğini ve bakım onarımlarını üstlenmek üzere 1988 yılında kurulmuştur. İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesine bağlı bir şirket olarak kurulan İstanbul Ulaşım AŞ, 20. hizmet yılına girmektedir. İstanbul Ulaşım A.Ş., İstanbul’daki metro, tramvay, funiküler sistem ve teleferiklerin işletmecisi durumundadır. İstanbul Esenler’ deki yönetim merkezinden koordine ettiği 800’ün üzerindeki personeli ile her gün yaklaşık 720.000 İstanbulluya hizmet vermektedir. İşletmeciliğini yaptığı raylı sistem hatlarının uzunluğu 64 km olan İstanbul Ulaşım A.Ş. 2007 yılında yaklaşık 250 milyon yolcuya hizmet götürmüştür. İstanbul Ulaşım AŞ, özellikle İstanbul gibi dev bir metropol ölçeğinde sürdürülebilir toplu taşımacılığın en önemli unsurunun raylı sistemler olduğuna inanmaktadır.