Colorblindness, a Life: Race, Film and the Articulation of an Ideology by Justin Daniel Gomer a Dissertation Submitted in Parti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Curtis Mayfield Super Fly Mp3, Flac, Wma

Curtis Mayfield Super Fly mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: Super Fly Country: Germany Released: 2014 Style: Soul MP3 version RAR size: 1278 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1823 mb WMA version RAR size: 1462 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 598 Other Formats: MIDI AU MP2 MP4 ASF DMF VOC Tracklist Superfly Original Soundtrack A1 Little Child Runnin' Wild 5:28 A2 Pusherman 5:07 A3 Freddie's Dead 5:31 A4 Junkie Chase (Instrumental) 1:42 A5 Give Me Your Love (Love Song) 4:21 B1 Eddie You Should Know Better 2:21 B2 No Thing On Me (Cocaine Song) 4:59 B3 Think (Instrumental) 3:49 B4 Superfly 3:56 Bonus Tracks (previously unrealeased on vinyl) B5 Ghetto Child (Little Child Runnin' Wild Demo) 3:21 B6 Militant March 0:56 B7 Radio Spot #1 0:29 C1 Pusherman (Alt. Mix With Horns) 6:12 C2 Freddie's Dead (Instrumental) 4:50 C3 Junkie Chase (Full Length Instrumental) 4:19 C4 Eddie You Should Know Better (Instrumental) 2:18 C5 The Natural Four - Eddie You Should Know Better 2:22 D1 Superfly (Single Mix) 3:12 D2 No Thing On Me (Cocaine Song) (Instrumental) 4:39 D3 Freddie's Dead (Single Mix) 3:21 D4 The Underground (Demo) 3:14 D5 Check Out Your Mind 4:08 D6 Radio Spot #2 0:24 Notes This release is the first to also include the bonus tracks on vinyl. Comes bundled with a CD in a cardboard sleeve - not to be sold seperately - containing the original album (tracks A1-B4) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 803415812813 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Super Fly (The Original Curtis Motion Picture -

Roots of Anger3 Notes

The Real Explanation for the Tax Rebellion and the Size of Government H. William Batt, Ph.D., February 16, 2011 The antipathy toward taxes, and by extension toward government itself, has its roots, I believe, in a distortion of economic theory that took place a century ago. Prior to that time, there was a tacit, if not explicit, understanding that the wealth and bounty that grew from common effort along with the gifts of nature should be the source of finance recaptured by society and used to pay for public services. Since surplus economic productivity is jointly produced, it was the proper source of taxation. Only government can appropriately provide these services since they are in today's language "public goods." On the other hand, wealth that was created by the people's own brains and brawn was rightfully theirs and theirs alone. Taxing people's labor, or the products thereof, was not only wrong but was tantamount to theft.1 Today the resentment people feel about taxes on their hard-earned money has reached a point close to delegitimizing the income tax and government itself. Estimates of actual tax cheating are put at about 15 percent, but fully half the population believes that it would be okay to cheat if one wouldn’t be caught.2 It has taken over a century for this all to explode. But taking the long view of tax history one could argue that this is not only understandable but also inevitable. Had economic arrangements been done as they were in earlier times there would likely be far less such resistance to taxation and perhaps even a sense of social duty to pay one’s share of taxes. -

Dena Derose, Vocals and Piano Martin Wind, Bass • Matt Wilson, Drums with Sheila Jordan, Vocal • Jeremy Pelt, Trumpet Houston Person, Tenor Saxophone

19 juin, 2020. June 19, 2020. MAN MAN DREAM HUNTING IN THE VALLEY OF THE IN-BETWEEN CD / 2XLP / CS / DIGITAL SP 1350 RELEASE DATE: MAY IST, 2020 TRACKLISTING: 1. Dreamers 2. Cloud Nein 3. On the Mend 4. Lonely Beuys 5. Future Peg 6. Goat 7. Inner Iggy 8. Hunters 9. Oyster Point 10. The Prettiest Song in the World 11. Animal Attraction 12. Sheela 13. Unsweet Meat 14. Swan 15. Powder My Wig 16. If Only 17. In the Valley of the In-Between GENRE: Alternative Rock Honus Honus (aka Ryan Kattner) has devoted his career to exploring the uncertainty between life’s extremes, beauty, and ugliness, order and chaos. The songs on Dream Hunting in the Valley of the In-Between, Man Man’s first album in over six years and their Sub Pop debut, are as intimate, soulful, and timeless as they are audaciously inventive and daring, resulting in his best Man Man album to date. 0 9 8 7 8 7 1 3 5 0 2 209 8 7 8 7 1 3 5 0 1 5 CD Packaging: Digipack 2xLP Packaging: Gatefold jacket w/ custom The 17-track effort, featuring “Cloud Nein,” “Future Peg,” “On the with poster insert dust sleeves and etching on side D Includes mp3 coupon Mend” “Sheela,” and “Animal Attraction,” was produced by Cyrus NON-RETURNABLE Ghahremani, mixed by S. Husky Höskulds (Norah Jones, Tom Waits, Mike Patton, Solomon Burke, Bettye LaVette, Allen Toussaint), and mastered by Dave Cooley (Blood Orange, M83, DIIV, Paramore, Snail Mail, clipping). Dream Hunting...also includes guest vocals from Steady Holiday’s Dre Babinski on “Future Peg” and “If Only,” and Rebecca Black (singer of the viral pop hit, “Friday”) on “On The Mend” and “Lonely Beuys.” The album follows the release of “Beached” and “Witch,“ Man Man’s contributions to Vol. -

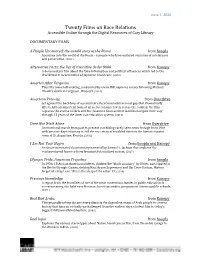

Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online Through the Digital Resources of Cary Library

June 1, 2020 Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online through the Digital Resources of Cary Library DOCUMENTARY FILMS A People Uncounted: the untold story of the Roma from hoopla A journey into the world of the Roma - a people who have endured centuries of intolerance and persecution. (2014) Alternative Facts: the lies of Executive Order 9066 from Kanopy A documentary film about the false information and political influences which led to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. (2018) America After Ferguson from Kanopy This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. (2014) American Promise from Overdrive Set against the backdrop of a persistent educational achievement gap that dramatically affects African-American boys at all socioeconomic levels across the country, the film captures the stories of Idris and his classmate Seun as their families navigate their way through 13 years of the American education system. (2013) Dare Not Walk Alone from Overdrive An emotional march from past to present combining rarely seen news footage from 1964 with present-day testimony to tell the true story of troubled times in the historic tourist town of St. Augustine, Florida. (2006) I Am Not Your Negro from hoopla and Kanopy An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson that explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. (2017) Olympic Pride, American Prejudice from hoopla In 1936, 18 African American athletes, dubbed the "black auxiliary" by Hitler, participated in the Berlin Olympic Games, defying Nazi Aryan Supremacy and Jim Crow Racism. -

Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex, Drugs and Rock and Roll Generation Saved Hollywood Pdf, Epub, Ebook

EASY RIDERS, RAGING BULLS: HOW THE SEX, DRUGS AND ROCK AND ROLL GENERATION SAVED HOLLYWOOD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Biskind | 512 pages | 26 Apr 1999 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780684857084 | English | New York, United States Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex, Drugs and Rock and Roll Generation Saved Hollywood PDF Book My impression of this documentary wasn't so great due to the fact of already seeing and knowing a similar themed work a few years ago called "A Decade Under the Influence" , directed by Ted Demme and Richard LaGravenese, which was a better project for numerous reasons. Why do people go see them? The book is hefty with gossip of all kinds, which is too bad because he's talking about the revolution in films in the 60's to early 80's. It is chock full of interviews and choice information about the time period 60's's in American cinema that changed everything, for a lot better and some for not. Beatty likes to fuck alot. Biskind's book disappointed me tremendously. Return to the Books Home Page. Assassinations, cultural domination, drugging, spying, provocation: Talk about taking the fight to your opponents—the American people—and crippling them for generations! But in the kind of popularized pseudohistory ''Easy Riders, Raging Bulls'' exemplifies, anecdotes are valued above all else, bitchy gossip is privileged, dysfunction is automatically more fascinating than artistic success, aggrieved former friends and former lovers are granted the license to settle scores sometimes anonymously , documentation is disdained and historical analysis must be squeezed into the narrative quickly, so as not to disrupt the dishing. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:408 J-POPピックアップアーティスト 放送日:2019/07/15~2019/07/21 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00〜/12:00〜/20:00〜 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■MAN WITH A MISSION 特集(1) NEVER FXXKIN' MIND THE RULES MAN WITH A MISSION 1997 MAN WITH A MISSION DANCE EVERYBODY MAN WITH A MISSION Smells Like Teen Spirit MAN WITH A MISSION Feel and Think MAN WITH A MISSION distance MAN WITH A MISSION フォーカスライト MAN WITH A MISSION FROM YOUTH TO DEATH MAN WITH A MISSION Get Off of My Way MAN WITH A MISSION Emotions MAN WITH A MISSION database ~アニメ「ログ・ホライズン」OPテーマ~ MAN WITH A MISSION feat. TAKUMA (10-FEET) higher MAN WITH A MISSION Seven Deadly Sins ~アニメ「七つの大罪」OPテーマ~ MAN WITH A MISSION Dive MAN WITH A MISSION ■MAN WITH A MISSION 特集(2) Out of Control MAN WITH A MISSION×Zebrahead Raise your flag ~アニメ「機動戦士ガンダム MAN WITH A MISSION 鉄血のオルフェンズ」OPテーマ~ Memories MAN WITH A MISSION Survivor MAN WITH A MISSION Dead End in Tokyo MAN WITH A MISSION My Hero MAN WITH A MISSION Find You MAN WITH A MISSION Take Me Under MAN WITH A MISSION Winding Road ~アニメ「ゴールデンカムイ」OPテーマ~ MAN WITH A MISSION Freak It! MAN WITH A MISSION feat. 東京スカパラダイスオーケストラ Remember Me MAN WITH A MISSION Left Alive MAN WITH A MISSION スターライト・シンドローム MAN WITH A MISSION FLY AGAIN 2019 MAN WITH A MISSION ■Superfly 特集(1) ハロー・ハロー Superfly マニフェスト Superfly i spy i spy Superfly×JET 愛をこめて花束を Superfly Hi-Five Superfly How Do I Survive? Superfly My Best Of My Life Superfly 恋する瞳は美しい Superfly やさしい気持ちで Superfly Alright!! Superfly Dancing On The Fire Superfly Wildflower Superfly タマシイレボリューション Superfly You & Me Superfly ■Superfly 特集(2) Eyes On Me ~ゲーム「The 3rd Birthday」テーマソング~ -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Mario Van Peebles's <I>Panther</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Communication Studies Communication Studies, Department of 8-2007 Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Auburn University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Hoerl, Kristen, "Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party" (2007). Papers in Communication Studies. 196. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Communication Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Critical Studies in Media Communication 24:3 (August 2007), pp. 206–227; doi: 10.1080/07393180701520900 Copyright © 2007 National Communication Association; published by Routledge/Taylor & Francis. Used by permission. Published online August 15, 2007. Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Department of Communication and Journalism, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA Corresponding author – Kristen Hoerl, email [email protected] Abstract The 1995 movie Panther depicted the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense as a vibrant but ultimately doomed social movement for racial and economic justice during the late 1960s. Panther’s narrative indicted the white-operated police for perpetuating violence against African Americans and for un- dermining movements for black empowerment. -

A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, American Film Studies Commons, and the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Airic, "A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1317. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1317 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Airic Hughes University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History and African and African American Studies, 2011 July 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. __________________ Dr. Calvin White Thesis Director __________________ __________________ Dr. Pearl Ford Dowe Dr. James Gigantino Committee Member Committee Member Abstract: Oscar Micheaux was a luminary who served as an agent of racial uplift, with a unique message to share with the world on behalf of the culturally marginalized African Americans. He produced projects that conveyed the complexity of the true black experience with passion and creative courage. His films empowered black audiences and challenged conventional stereotypes of black culture and potential. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs.