Mario Van Peebles's <I>Panther</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

Celebrity and Race in Obama's America. London

Cashmore, Ellis. "To be spoken for, rather than with." Beyond Black: Celebrity and Race in Obama’s America. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 125–135. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781780931500.ch-011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 05:30 UTC. Copyright © Ellis Cashmore 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 11 To be spoken for, rather than with ‘“I’m not going to put a label on it,” said Halle Berry about something everyone had grown accustomed to labeling. And with that short declaration she made herself arguably the most engaging black celebrity.’ uperheroes are a dime a dozen, or, if you prefer, ten a penny, on Planet SAmerica. Superman, Batman, Captain America, Green Lantern, Marvel Girl; I could fi ll the rest of this and the next page. The common denominator? They are all white. There are benevolent black superheroes, like Storm, played most famously in 2006 by Halle Berry (of whom more later) in X-Men: The Last Stand , and Frozone, voiced by Samuel L. Jackson in the 2004 animated fi lm The Incredibles. But they are a rarity. This is why Will Smith and Wesley Snipes are so unusual: they have both played superheroes – Smith the ham-fi sted boozer Hancock , and Snipes the vampire-human hybrid Blade . Pulling away from the parallel reality of superheroes, the two actors themselves offer case studies. -

Co-Produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the Vision

Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the vision. the voice. From LA to London and Martinique to Mali. We bring you the world ofBlack film. Ifyou're concerned about Black images in commercial film and tele vision, you already know that Hollywood does not reflect the multi- cultural nature 'ofcontemporary society. You know thatwhen Blacks are not absent they are confined to predictable, one-dimensional roles. You may argue that movies and television shape our reality or that they simply reflect that reality. In any case, no one can deny the need to take a closer look atwhat is COIning out of this powerful medium. Black Film Review is the forum you've been looking for. Four times a year, we bringyou film criticiSIn froIn a Black perspective. We look behind the surface and challenge ordinary assurnptiorls about the Black image. We feature actors all.d actresses th t go agaul.st the graill., all.d we fill you Ul. Oll. the rich history ofBlacks Ul. Arnericall. filrnrnakul.g - a history thatgoes back to 19101 And, Black Film Review is the only magazine that bringsyou news, reviews and in-deptll interviews frOtn tlle tnost vibrant tnovetnent in contelllporary film. You know about Spike Lee butwIlat about EuzIlan Palcy or lsaacJulien? Souletnayne Cisse or CIl.arles Burnette? Tllrougll out tIle African cliaspora, Black fi1rnInakers are giving us alternatives to tlle static itnages tIlat are proeluceel in Hollywood anel giving birtll to a wIlole new cinetna...be tIlere! Interview:- ----------- --- - - - - - - 4 VDL.G NO.2 by Pat Aufderheide Malian filmmaker Cheikh Oumar Sissoko discusses his latest film, Finzan, aself conscious experiment in storytelling 2 2 E e Street, NW as ing on, DC 20006 MO· BETTER BLUES 2 2 466-2753 The Music 6 o by Eugene Holley, Jr. -

Queens of Consciousness & Sex-Radicalism in Hip-Hop

Queens of Consciousness & Sex-Radicalism in Hip-Hop: On Erykah Badu & The Notorious K.I.M. by Greg Thomas, Ph.D. English Department Syracuse University Greg Thomas ([email protected]) is an Assistant Professor in the English Department at Syracuse University. His interests include Pan-Africanism, Hip-Hop and Black radical traditions. He is author of The Sexual Demon of Colonial Power: Pan-African Embodiment and Erotic Schemes of Empire (Indiana University Press, 2007). He is also editor of the e-journal, Proud Flesh: New Afrikan Journal of Culture, Politics & Consciousness. Abstract This article is a study of sex, politics and lyrical literature across what could be called “Hip-Hop & Hip-Hop Soul.” It champions the concept “sexual consciousness” against popular and academic assumptions that construe “sexuality” and “consciousness” to be antithetical--in the tradition of “the mind/body split” of the white bourgeois West. An alternative, radical articulation of consciousness with an alternative, radical politics of gender and sexuality is located in the musical writings of two contemporary “iconic” figures: Lil’ Kim of “Hip-Hop” and Erykah Badu of “Neo-Soul.” Underscoring continuities between these author-figures, one of whom is coded as an icon of “sexuality (without consciousness),” conventionally, and the other as an icon of “consciousness (without sexuality),” I show how Black popular music is a space where radical sexual identities and epistemic politics are innovated out of vibrant African/Diasporic traditions. 23 The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 1, no. 7, March 2007 The reputed “Father of African Cinema,” Ousmane Sembène is perhaps ironically famous for what we can call his sexual consciousness, a consciousness of the politics of sex or gender and sexuality, in his radical productions of Black independent film. -

Stallings Book 4 Print.Pdf (3.603Mb)

Black Performance and Cultural Criticism Valerie Lee and E. Patrick Johnson, Series Editors Stallings_final.indb 1 5/17/2007 5:14:41 PM Stallings_final.indb 2 5/17/2007 5:14:41 PM Mutha ’ is half a word Intersections of Folklore, Vernacular, Myth, and Queerness in Black Female Culture L. H. Stallings The Ohio State University Press Columbus Stallings_final.indb 3 5/17/2007 5:14:42 PM Copyright © 2007 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Horton-Stallings, LaMonda. Mutha’ is half a word : intersections of folklore, vernacular, myth, and queerness in black female culture / L.H. Stallings. p. cm.—(Black performance and cultural criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1056-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1056-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9135-1 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9135-X (cd-rom) 1. American literature—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. American literature—women authors—History and criticism. 3. African American women in literature. 4. Lesbianism in literature. 5. Gender identity in literature. 6. African American women— Race identity. 7. African American women—Intellectual life. 8. African American women— Folklore. I. Title. II. Series PS153.N5H68 2007 810.9'353—dc22 2006037239 Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Cover illustration by Michel Isola from shutterstock.com. Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe in Adobe Garamond. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

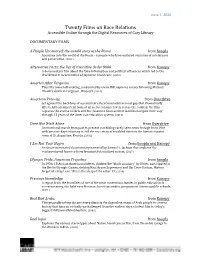

Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online Through the Digital Resources of Cary Library

June 1, 2020 Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online through the Digital Resources of Cary Library DOCUMENTARY FILMS A People Uncounted: the untold story of the Roma from hoopla A journey into the world of the Roma - a people who have endured centuries of intolerance and persecution. (2014) Alternative Facts: the lies of Executive Order 9066 from Kanopy A documentary film about the false information and political influences which led to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. (2018) America After Ferguson from Kanopy This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. (2014) American Promise from Overdrive Set against the backdrop of a persistent educational achievement gap that dramatically affects African-American boys at all socioeconomic levels across the country, the film captures the stories of Idris and his classmate Seun as their families navigate their way through 13 years of the American education system. (2013) Dare Not Walk Alone from Overdrive An emotional march from past to present combining rarely seen news footage from 1964 with present-day testimony to tell the true story of troubled times in the historic tourist town of St. Augustine, Florida. (2006) I Am Not Your Negro from hoopla and Kanopy An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson that explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. (2017) Olympic Pride, American Prejudice from hoopla In 1936, 18 African American athletes, dubbed the "black auxiliary" by Hitler, participated in the Berlin Olympic Games, defying Nazi Aryan Supremacy and Jim Crow Racism. -

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema Author Howell, Amanda Published 2005 Journal Title Screening the Past Copyright Statement © The Author(s) 2005. The attached file is posted here with permission of the copyright owner for your personal use only. No further distribution permitted. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/4130 Link to published version http://www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Amanda Howell "Blaxploitation" was a brief cycle of action films made specifically for black audiences in both the mainstream and independent sectors of the U.S. film industry during the early 1970s. Offering overblown fantasies of black power and heroism filmed on the sites of race rebellions of the late 1960s, blaxploitation films were objects of fierce debate among social leaders and commentators for the image of blackness they projected, in both its aesthetic character and its social and political utility. After some time spent as the "bad object" of African-American cinema history,[1] critical and theoretical interest in blaxploitation resurfaced in the 1990s, in part due to the way that its images-- and sounds--recirculated in contemporary film and music cultures. Since the early 1990s, a new generation of African-American filmmakers has focused -

The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 7-2009 Framing Red Power: The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media Jason A. Heppler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the History Commons Heppler, Jason A., "Framing Red Power: The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FRAMING RED POWER: THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT, THE TRAIL OF BROKEN TREATIES, AND THE POLITICS OF MEDIA By Jason A. Heppler A Thesis Presented to the Faculty The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Wunder Lincoln, Nebraska July 2009 2 FRAMING RED POWER: THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT, THE TRAIL OF BROKEN TREATIES, AND THE POLITICS OF MEDIA Jason A. Heppler, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2009 Adviser: John R. Wunder This study explores the relationship between the American Indian Movement (AIM), national newspaper and television media, and the Trail of Broken Treaties caravan in November 1972 and the way media framed, or interpreted, AIM's motivations and objectives. -

Racial Equity Resource Guide

RACIAL EQUITY RESOURCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 7 An Essay by Michael R. Wenger 17 Racial Equity/Racial Healing Tools Dialogue Guides and Resources Selected Papers, Booklets and Magazines Racial Equity Toolkits and Guides to Action Workshops, Convenings and Training Curricula 61 Anchor Organizations 67 Institutions Involved in Research on Structural Racism 83 National Organizing and Advocacy Organizations 123 Media Outreach Traditional Media Social Media 129 Recommended Articles, Books, Films, Videos and More Recommended Articles: Structural/Institutional Racism/Racial Healing Recommended Books Recommended Sources for Documentaries, Videos and Other Materials Recommended Racial Equity Videos, Narratives and Films New Orleans Focused Videos Justice/Incarceration Videos 149 Materials from WKKF Convenings 159 Feedback Form 161 Glossary of Terms for Racial Equity Work About the Preparer 174 Index of Organizations FOREWORD TO THE AMERICA HEALING COMMUNITY, When the W.K. Kellogg Foundation launched America Healing, we set for ourselves the task of building a community of practice for racial healing and equity. Based upon our firm belief that our greatest asset as a foundation is our network of grantees, we wanted to link together the many different organizations whose work we are now supporting as part of a broad collective to remove the racial barriers that limit opportunities for vulnerable children. Our intention is to ensure that our grantees and the broader community can connect with peers, expand their perceptions about possibilities for their work and deepen their understanding of key strategies and tactics in support of those efforts. In 2011, we worked to build this community We believe in a different path forward. -

Transcript a Pinewood Dialogue with Melvin And

TRANSCRIPT A PINEWOOD DIALOGUE WITH MELVIN AND MARIO VAN PEEBLES Legendary maverick Melvin Van Peebles is a novelist, composer, and filmmaker who has also worked in television, popular music, and theater. After spending the 1960s in Paris, he returned to the United States and made the groundbreaking 1971 film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song . The stunning box-office success of this subversive and sexy film paved the way for filmmakers such as Mario Van Peebles, who directed New Jack City and Panther . Mario paid tribute to his father with his 2003 movie Baadasssss ; in this lively discussion, Van Peebles père et fils share a lifetime of experience and a playful father-son rivalry. A Pinewood Dialogue following a screening of course, when I made my first films, I went down to Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song , Hollywood and they offered me a job, but as an moderated by Chief Curator David Schwartz elevator operator. I said, “No, I don’t want—I want (May 8, 2004): to really be in front of the camera or doing creative things.” And that was—they offered me a job as a SCHWARTZ : Please welcome Melvin and Mario Van dancer. Peebles. (Applause) Anyway, long story short, I went to Holland. Melvin, your first experience in Hollywood was Through another fluke that’s too long to go into doing comedies. Of course, you did Watermelon here, my short films that had been turned down in Man . I guess you were with Universal for a while; Hollywood were seen in France, and France invited you were signed on. -

The Hilltop 4-11-2003

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 The iH lltop Digital Archive 4-11-2003 The iH lltop 4-11-2003 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 4-11-2003" (2003). The Hilltop: 2000 - 2010. 122. https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010/122 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFE&STYLE Men who refuse to identify as gay, bisexual or THE straight... Bl The Student Voice of Howard1/ University. Since 1924 VOLUME 86, NO. 54 FRIDAY, APR.JL 11, 2003 ,/ www.thehilltoponline.com . Morris Brown Loses Accreditation By Kerry-Ann Hamilton accreditation loss is severe. Howard University · Campus Editor Morris Brown will immediately President H. Patrick Swygert lose access to millions of dollars commends the efforts of the Despite the tireless efforts of in federal financial assistance, Howard faculty, staff and espe several members of the Howard which approximately 90 percent cially the students that worked University community to stop of its students receive. relentlessly to bring the plight of sister school Morris Brown The loss of accreditation Morris Brown to the forefront. College from losing their accred- also suspends the school's affilir "Our efforts here at Howard itation, what was feared has ation with the United Negro University have not failed," occurred. -

Art 8 Vol III Is 2

Qualitative Sociology Review Volume III, Issue 2 – August 2007 Wendy Leo Moore Texas A&M University, USA Jennifer Pierce University of Minnesota, USA Still Killing Mockingbirds: Narratives of Race and Innocence in Hollywood’s Depiction of the White Messiah Lawyer Abstract Through a narrative analysis of movies confronting issues of race and racism in the post-civil rights era, we suggest that the movie To Kill a Mockingbird ushered in a new genre for movies about race which presented an image of a white male hero, or perhaps savior, for the black community. We suggest that this genre outlasted the era of the Civil Rights Movement and continues to impact popular cultural discourses about race in post-civil rights America. Post-civil rights films share the central elements of the anti-racist white male hero genre, but they also provide a plot twist that simultaneously highlights the racial innocence of the central characters and reinforces the ideology of liberal individualism. Reading these films within their broader historical context, we show how the innocence of these characters reflects not only the recent neo-conservative emphasis on “color blindness,” but presents a cinematic analogue to the anti-affirmative action narrative of the innocent white victim. Keywords Race; Racism; Film; Popular culture; Whiteness The film, To Kill a Mockingbird , based on Harper Lee’s eponymous book, was produced in the early 1960s, in the midst of the civil rights movement. Its narrative focuses on the valiant efforts of a small town lawyer, Atticus Finch, who defends Tom Robinson, a black man wrongfully accused of rape, against the racism of the Jim Crow South.