Black Skin, White Gaze: the Presence and Function of the Linchpin Character in Biopics About Black American Protagonists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Textual Analysis Film: Do the Right Thing (1989) Director: Spike Lee Sequence Running Time: 00:50:55 - 00:55:55 Word Count: 1745

Student sample Textual Analysis Film: Do The Right Thing (1989) Director: Spike Lee Sequence Running Time: 00:50:55 - 00:55:55 Word Count: 1745 In this paper I will analyze an extract from Spike Lee's Do The Right Thing (1989) that reflects the political, geographical, social, and economical situations through Lee's stylistic use of cinematography, mise-en-scene, editing, and sound to communicate the dynamics of the characters in the cultural melting pot that is Bedford-Stuyvesant,Brooklyn in New York City. This extract manifests Lee's artistic visions that are prevalent in the film and are contemplative of Lee's personal experience of growing up in Brooklyn. "This evenhandedness that is at the center of Spike Lee's work" (Ebert) is evident through Lee's techniques and the equal attention given to the residents of this neighborhood to present a social realism cinema. Released almost thirty years ago, Lee's film continues to empower the need for social change today with the Black Lives Matter movement and was even called "'culturally significant'by the U.S. Library of Congress" (History). Do The Right Thing takes place during the late 1980s in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn and unravels the "bigotry and violence" (Lee) in the neighborhood of a single summer day, specifically one of the hottest of the season. Being extremely socially conscious, Do The Right Thing illustrates the dangers of racism against African Americans and was motivated by injusticesof the time--especially in New York--such as the death of Yusef Hawkins and the Howard Beach racial incident. -

Movie List Please Dial 0 to Request

Movie List Please dial 0 to request. 200 10 Cloverfield Lane - PG13 38 Cold Pursuit - R 219 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi - R 46 Colette - R 202 5th Wave, The - PG13 75 Collateral Beauty - PG13 11 A Bad Mom’s Christmas - R 28 Commuter, The-PG13 62 A Christmas Story - PG 16 Concussion - PG13 48 A Dog’s Way Home - PG 83 Crazy Rich Asians - PG13 220 A Star is Born - R 20 Creed - PG13 32 A Walk Among the Tombstones - R 21 Creed 2 - PG13 4 Accountant, The - R 61 Criminal - R 19 Age of Adaline, The - PG13 17 Daddy’s Home - PG13 40 Aladdin - PG 33 Dark Tower, The - PG13 7 Alien:Covenant - R 67 Darkest Hour-PG13 2 All is Lost - PG13 52 Deadpool - R 9 Allied - R 53 Deadpool 2 - R (Uncut) 54 ALPHA - PG13 160 Death of a Nation - PG13 22 American Assassin - R 68 Den of Thieves-R (Unrated) 37 American Heist - R 34 Detroit - R 1 American Made - R 128 Disaster Artist, The - R 51 American Sniper - R 201 Do You Believe - PG13 76 Annihilation - R 94 Dr. Suess’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas - PG 5 Apollo 11 - G 233 Dracula Untold - PG13 23 Arctic - PG13 113 Drop, The - R 36 Assassin’s Creed - PG13 166 Dunkirk - PG13 39 Assignment, The - R 137 Edge of Seventeen, The - R 64 At First Light - NR 88 Elf - PG 110 Avengers:Infinity War - PG13 81 Everest - PG13 49 Batman Vs. Superman:Dawn of Justice - R 222 Everybody Wants Some!! - R 18 Before I Go To Sleep - R 101 Everything, Everything - PG13 59 Best of Me, The - PG13 55 Ex Machina - R 3 Big Short, The - R 26 Exodus Gods and Kings - PG13 50 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk - R 232 Eye In the Sky - -

The Hidden Earth: Visualization of Geologic Features and Their Subsurface Geometry

The Hidden Earth: Visualization of Geologic Features and their Subsurface Geometry Michael D. Piburn, Stephen J. Reynolds, Debra E. Leedy, Carla M. McAuliffe, James P. Birk, and Julia K. Johnson ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, New Orleans, LA, April 7-10, 2002. ABSTRACT Geology is among the most visual of the sciences, with spatial reasoning taking place at various scales and in various contexts. Among the spatial skills required in introductory college geology courses are spatial rotation (rotating objects in one’s mind), and visualization (transforming an object in one’s mind). To assess the role of spatial ability in geology, we designed an experiment using (1) web-based versions of spatial visualization tests, (2) a geospatial test, and (3) multimedia instructional modules built around innovative QuickTime Virtual Reality (QTVR) movies. Two introductory geology modules were created – visualizing topography and interactive 3D geologic blocks. The topography module was created with Authorware and encouraged students to visualize two-dimensional maps as three-dimensional landscapes. The geologic blocks module was created in FrontPage and covered layers, folds, faults, intrusions, and unconformities. Both modules had accompanying worksheets and handouts to encourage active participation by describing or drawing various features, and both modules concluded with applications that extended concepts learned during the program. Computer-based versions of paper-based tests were created for this study. Delivering the tests by computer made it possible to remove the verbal cues inherent in the paper-based tests, present animated demonstrations as part of the instructions for the tests, and collect time-to-completion measures on individual items. -

Winning Jazz Pianist Robert

Media Advisory Contact: Molly Hogin (310) 974-6680 | [email protected] GRAMMY-NOMINATED PRODUCER/MUSICIAN TERRACE MARTIN TEAMS UP WITH GRAMMY- WINNING JAZZ PIANIST ROBERT GLASPER FOR MILES DAVIS 90th BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE The Jazz Creative and All Music Television Partner in Community-Wide Celebration #Miles90, Hosted by Baldwin Hills Crenshaw LOS ANGELES— GRAMMY-nominated producer/musician Terrace Martin will join GRAMMY-winning jazz pianist Robert Glasper for a tribute to Miles Davis on May 19, hosted by Baldwin Hills Crenshaw in partnership with The Jazz Creative and All Music Television. The celebration honors internationally renowned music icon Miles Davis in recognition of what would have been his 90th birthday on May 26. The music, art, and cultural festivities feature Terrace Martin, who will perform a special Miles Davis tribute. Martin is one of the key collaborators on Kendrick Lamar's multi-GRAMMY award-winning album To Pimp A Butterfly. Robert Glasper, who scored the Miles Ahead soundtrack and produced the forthcoming "re-imagined" interpretations of Davis’s music titled Everything’s Beautiful (out May 27) featuring Stevie Wonder, Erykah Badu and Bilal among others, will also participate in a behind-the- scenes interview. Additional young contemporary artists will also honor and celebrate Davis during #Miles90. Visuals will be provided by jazz portrait artist Jazmin Hicks, whose work will be on display throughout the event. The Jazz Creative is a weekly television series dedicated to jazz and blues hosted on All Music Television, among the most relevant and popular jazz websites. Baldwin Hills Crenshaw, located in South Los Angeles, has long been referred to as the “Harlem of the West" and is known for fostering local and touring musicians since the 1930s. -

Questioning Whiteness: “Who Is White?”

人間生活文化研究 Int J Hum Cult Stud. No. 29 2019 Questioning Whiteness: “Who is white?” ―A case study of Barbados and Trinidad― Michiru Ito1 1International Center, Otsuma Women’s University 12 Sanban-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan 102-8357 Key words:Whiteness, Caribbean, Barbados, Trinidad, Oral history Abstract This paper seeks to produce knowledge of identity as European-descended white in the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Trinidad, where the white populations account for 2.7% and 0.7% respectively, of the total population. Face-to-face individual interviews were conducted with 29 participants who are subjectively and objectively white, in August 2016 and February 2017 in order to obtain primary data, as a means of creating oral history. Many of the whites in Barbados recognise their interracial family background, and possess no reluctance for having interracial marriage and interracial children. They have very weak attachment to white hegemony. On contrary, white Trinidadians insist on their racial purity as white and show their disagreement towards interracial marriage and interracial children. The younger generations in both islands say white supremacy does not work anymore, yet admit they take advantage of whiteness in everyday life. The elder generation in Barbados say being white is somewhat disadvantageous, but their Trinidadian counterparts are very proud of being white which is superior form of racial identity. The paper revealed the sense of colonial superiority is rooted in the minds of whites in Barbados and Trinidad, yet the younger generations in both islands tend to deny the existence of white privilege and racism in order to assimilate into the majority of the society, which is non-white. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

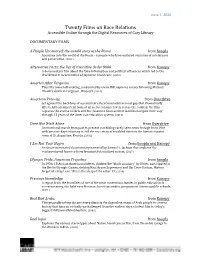

Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online Through the Digital Resources of Cary Library

June 1, 2020 Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online through the Digital Resources of Cary Library DOCUMENTARY FILMS A People Uncounted: the untold story of the Roma from hoopla A journey into the world of the Roma - a people who have endured centuries of intolerance and persecution. (2014) Alternative Facts: the lies of Executive Order 9066 from Kanopy A documentary film about the false information and political influences which led to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. (2018) America After Ferguson from Kanopy This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. (2014) American Promise from Overdrive Set against the backdrop of a persistent educational achievement gap that dramatically affects African-American boys at all socioeconomic levels across the country, the film captures the stories of Idris and his classmate Seun as their families navigate their way through 13 years of the American education system. (2013) Dare Not Walk Alone from Overdrive An emotional march from past to present combining rarely seen news footage from 1964 with present-day testimony to tell the true story of troubled times in the historic tourist town of St. Augustine, Florida. (2006) I Am Not Your Negro from hoopla and Kanopy An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson that explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. (2017) Olympic Pride, American Prejudice from hoopla In 1936, 18 African American athletes, dubbed the "black auxiliary" by Hitler, participated in the Berlin Olympic Games, defying Nazi Aryan Supremacy and Jim Crow Racism. -

Teaching Critical Whiteness Theory: What College and University Teachers Need to Know

Understanding and Dismantling Privilege Nichols, Teaching Critical Whiteness 1 Teaching Critical Whiteness Theory: What College and University Teachers Need to Know Dana Nichols St. John Fisher College My small, four‐year, regional, upstate New York college is similar to many colleges and universities across the country. It has a predominantly white student population, comprised primarily of middle‐ and working‐class students. The majority of my students are from rural, economically depressed, racially homogenous areas. When planning my first critical whiteness theory course, I knew that most, if not all of my students, would be white. I also knew that my class would probably be the first time white students had been asked to think about their racial identity in a formal educational setting and that they would need as many tools as I could offer them to critically engage with whiteness. I anticipated that I would encounter some resistant students, while other students would eagerly embrace a new way of thinking about themselves and the world, and I wanted to feel as prepared as possible for both kinds of students. In planning my own classes, I have turned to recent scholarship to glean some advice about how to build a successful whiteness studies class. This paper is a brief overview of some of those ideas and it covers four major areas: (1) the attitudes that white students bring with them, (2) the goals of critical whiteness pedagogy, (3) the potential pitfalls of critical whiteness pedagogy, and (4) strategies for counteracting the pitfalls. Volume 1, Issue 1, August 2010 Understanding and Dismantling Privilege Nichols, Teaching Critical Whiteness 2 When teachers think about the attitudes white students bring with them to the college classroom, they sometimes assume that white students have no awareness of themselves as racial subjects. -

More at Sutv.Nova.Edu!

Watch all these movies and more at sutv.nova.edu! Movie Show Times: November 1-30, 2017 [email protected] www.nova.edu/sutv (954) 262-2602 Date 12:30a 2:30a 4:30a 6:30a 8:30a 11:00a 1:00p 3:30p 5:30p 8:00p 10:00p Open Water 3: The Book Spider-Man: Deep A Ghost Story The House Wish Upon Admission Lady Macbeth Personal Shopper The Emoji Movie 1-Nov Cage Dive of Henry Homecoming Open Water 3: Spider-Man: The House City of Ghost The Beguiled Girls Trip Kidnap Despicable Me Les Miserables Landline (8:15p) Baby Driver 2-Nov Cage Dive Homecoming The Book The Beguiled Wish Upon City of Ghost Lady Macbeth Legally Blonde The Emoji Movie Personal Shopper A Ghost Story Baby Driver Deep 3-Nov of Henry Open Water 3: Spider-Man: Lady Macbeth Kidnap Wish Upon Despicable Me Landline Les Miserables Cage Dive Admission The House Girls Trip 4-Nov Homecoming (3:45p) Spider-Man: Personal Despicable Me The Emoji Movie Kidnap A Ghost Story Baby Driver Deep Girls Trip City of Ghost The Beguiled 5-Nov Homecoming Shopper Open Water 3: Spider-Man: A Ghost Story Landline The Emoji Movie Personal Shopper The House Legally Blonde Wish Upon The Book of Henry Lady Macbeth 6-Nov Cage Dive Homecoming Open Water 3: Spider-Man: Despicable Me Cage Dive Deep Landline City of Ghost Girls Trip The Beguiled Kidnap Les Miserables Admission 7-Nov Homecoming (8:15p) (12:45a) The Book Spider-Man: City of Ghost The House Deep Wish Upon Lady Macbeth Admission The Emoji Movie Personal Shopper A Ghost Story 8-Nov of Henry Homecoming Open Water 3: Spider-Man: Wish Upon The Beguiled The -

Mario Van Peebles's <I>Panther</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Communication Studies Communication Studies, Department of 8-2007 Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Auburn University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Hoerl, Kristen, "Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party" (2007). Papers in Communication Studies. 196. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Communication Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Critical Studies in Media Communication 24:3 (August 2007), pp. 206–227; doi: 10.1080/07393180701520900 Copyright © 2007 National Communication Association; published by Routledge/Taylor & Francis. Used by permission. Published online August 15, 2007. Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Department of Communication and Journalism, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA Corresponding author – Kristen Hoerl, email [email protected] Abstract The 1995 movie Panther depicted the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense as a vibrant but ultimately doomed social movement for racial and economic justice during the late 1960s. Panther’s narrative indicted the white-operated police for perpetuating violence against African Americans and for un- dermining movements for black empowerment. -

Jada Pinkett Smith, Queen Latifah, Regina Hall and Tiffany Haddish Star in a Laugh-Out-Loud Summer Movie About Taking a Trip to the Essence Festival

GIRL TRIPPING JADA PINKETT SMITH, QUEEN LATIFAH, REGINA HALL AND TIFFANY HADDISH STAR IN A LAUGH-OUT-LOUD SUMMER MOVIE ABOUT TAKING A TRIP TO THE ESSENCE FESTIVAL. REGINA R. ROBERTSON TAGS ALONG FOR THE WILD RIDE PHOTOGRAPHY BY WARWICK SAINT 82 ESSENCE.COM JULY 2017 This page: Pinkett URING THE THICK OF SUMMER, Smith wears a built a brand based on perfection. is to wreak as much havoc as humanly possible over July Fourth weekend. it’s nearly impossible to escape the Mugler dress, Then there’s seemingly levelheaded Along with the group’s barhopping up and down Bourbon Street and earrings grip of New Orleans’ heat. Stand- Altuzarra Sasha (Latifah), a reluctant gossip dancing in the aisles of the Superdome—while Kendrick Lamar, Maxwell, New and Le Silla pumps. ing beneath a tree, hoping for even c olumnist who’s determined to live Edition, Diddy and Mariah Carey rock the Festival stage—the level of fun in the slightest hint of cool, doesn’t Opening spread: her best life despite her rocky which Ryan, Sasha, Lisa and Dina indulge sways between reckless abandon and On Jada: a Christian do the trick. Nor does sipping finances. A former wild child and straight-up debauchery, including one hilarious scene with a scantily clad Siriano dress, Dana strawberryD lemonade with an ice water chaser. Rebecca Designs current divorced mom of two, Lisa Siriboe. (Thank you, Mr. Lee.) Back at the Pink Motel, Pinkett Smith cracks up It’s sweltering, from sunup to sundown, and the earrings. Ring, (Pinkett Smith) has b ecome so about all that his character Malik endures: “Awww, poor Kofi. -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010).