Vibing with Blackness: Critical Considerations of Black Panther and Exceptional Black Positionings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvel Studios' Black Panther Activity Packet

ACTIVITY PACKET Created in Partnership with Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment CONTENTS: Welcome to Wakanda 4 Meet the Characters 5 The Mantle of Black Panther 6 The Strength of Nature 8 Zuri’s Wisdom 10 Shuri’s Technology Hunt 12 Horns & Heroes 14 Acknowledgments Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment would like to take this opportunity to thank the amazing teams that came together to develop the “Black Panther” Activity Packet. It was created with great care, collaboration and the talent and hard work of many incredible individuals. A special thank you to Dr. Mark Penning for his ongoing support in developing engaging educational materials that arvel Studios’ “Black Panther” follows T’Challa who, after the death of his father, the connect families with nature. These materials would not have happened without the diligence and King of Wakanda, returns home to the isolated, technologically advanced African nation dedication of Kyle Huetter who worked side by side with the filmmakers and educators to help M create these compelling activities and authored the unique writing found throughout each page. to succeed to the throne and take his rightful place as king. But when a powerful old enemy A big thank you to Hannah O’Malley, Cruzz Bernales and Elyssa Finkelstein whose creative reappears, T’Challa’s mettle as king—and Black Panther—is tested when he is drawn into a thinking and artistry developed games and crafts into a world of outdoor exploration for the superhero in all of us. Special thanks to director Ryan Coogler and producer Kevin Feige, formidable conflict that puts the fate of Wakanda and the entire world at risk. -

Captain America

The Star-spangled Avenger Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Captain America first appeared in Captain America Comics #1 (Cover dated March 1941), from Marvel Comics' 1940s predecessor, Timely Comics, and was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. For nearly all of the character's publication history, Captain America was the alter ego of Steve Rogers , a frail young man who was enhanced to the peak of human perfection by an experimental serum in order to aid the United States war effort. Captain America wears a costume that bears an American flag motif, and is armed with an indestructible shield that can be thrown as a weapon. An intentionally patriotic creation who was often depicted fighting the Axis powers. Captain America was Timely Comics' most popular character during the wartime period. After the war ended, the character's popularity waned and he disappeared by the 1950s aside from an ill-fated revival in 1953. Captain America was reintroduced during the Silver Age of comics when he was revived from suspended animation by the superhero team the Avengers in The Avengers #4 (March 1964). Since then, Captain America has often led the team, as well as starring in his own series. Captain America was the first Marvel Comics character adapted into another medium with the release of the 1944 movie serial Captain America . Since then, the character has been featured in several other films and television series, including Chris Evans in 2011’s Captain America and The Avengers in 2012. The creation of Captain America In 1940, writer Joe Simon conceived the idea for Captain America and made a sketch of the character in costume. -

Afrofuturism in Animation: Self Identity of African Americans in Cinematic Storytelling

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- 2020 Afrofuturism in Animation: Self Identity of African Americans in Cinematic Storytelling Dana Barnes University of Central Florida Part of the Film Production Commons, and the Illustration Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Barnes, Dana, "Afrofuturism in Animation: Self Identity of African Americans in Cinematic Storytelling" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020-. 14. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/14 AFROFUTURISM IN ANIMATION: SELF-IDENTITY OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN CINEMATIC STORYTELLING by DANA BARNES BFA University of Central Florida 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Visual Arts and Design in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2020 Major Professor: JoAnne Adams ©DANA B BARNES II 2020 ii ABSTRACT My work addresses the importance of self-identity within Black culture in the United States of America through the depiction of an African American boy who must look into himself to overcome a difficult bullying situation. Animation as a medium is an ideal tool for interrogating the Western perspective of identity through cinematic storytelling. Using established animation methods, I created a visual narrative to portray the impact self-identity has on an individual's actions in certain social conditions. -

Marvel/ Dc Secret Files A.R.G.U.S / S.H.I.E.L.D

MARVEL/ DC SECRET FILES During these sessions you will take place of one of these superheroes from both worlds to discuss the take on action, the strategy, explain the reasons to proceed from certain way and giving enough intelligence and ideas to approach conflicted countries and regions where certain heroes from an specific nationality couldn’t enter due to political motives. OVERVIEW Dangerous objects and devices have fallen into the hands of both Marvel and DC villains. It is the mission of the UN to assign rescue missions of these objects located in different parts of both universes to avoid a possible collision of worlds and being used against humanity. The General Assembly of the United Nations and the Security Council has given special powers to heroes of different countries (and universes) to take action on behalf of the governments of the world to avoid a catastrophe and to be able to fight with the opposing forces that have taken possession of these devices, threatening humanity with them and disrupting world peace forming a Special Force. Recon missions have been done by Black Widow, Catwoman, Hawkeye and Plastic Man and we have gathered information of different objects that are guarded by villains in different locations of both universes. Some in the Marvel universe and others in the DC universe. Each artifact has been enclosed in a magic bubble that prevents its use to any being that has possession of it. But this enchantment created by Doctor Strange and Doctor Fate has expiration time. Within 48 hours, it will be deactivated and anyone who has any of these devices in their possession will be able to freely use them. -

The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs

I The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs: Lost Races and Racism in American Popular Culture James R. Nesteby Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy August 1978 Approved: © 1978 JAMES RONALD NESTEBY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ¡ ¡ in Abstract The Tarzan series of Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950), beginning with the All-Story serialization in 1912 of Tarzan of the Apes (1914 book), reveals deepseated racism in the popular imagination of early twentieth-century American culture. The fictional fantasies of lost races like that ruled by La of Opar (or Atlantis) are interwoven with the realities of racism, particularly toward Afro-Americans and black Africans. In analyzing popular culture, Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932) and John G. Cawelti's Adventure, Mystery, and Romance (1976) are utilized for their indexing and formula concepts. The groundwork for examining explanations of American culture which occur in Burroughs' science fantasies about Tarzan is provided by Ray R. Browne, publisher of The Journal of Popular Culture and The Journal of American Culture, and by Gene Wise, author of American Historical Explanations (1973). The lost race tradition and its relationship to racism in American popular fiction is explored through the inner earth motif popularized by John Cleves Symmes' Symzonla: A Voyage of Discovery (1820) and Edgar Allan Poe's The narrative of A. Gordon Pym (1838); Burroughs frequently uses the motif in his perennially popular romances of adventure which have made Tarzan of the Apes (Lord Greystoke) an ubiquitous feature of American culture. -

Sundance Institute Expands Support to Writers and Creators of Series for TV and Online Platforms

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: March 19, 2014 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute Expands Support to Writers and Creators of Series for TV and Online Platforms First ‘Sundance Institute Episodic Story Lab’ to Be Held in Fall 2014 at the Sundance Resort, with Norman and Lyn Lear as Founding Supporters Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute today announced a significant expansion of its renowned labs for independent artists to include dedicated support for writers and creators of series for television and online platforms. The first Sundance Institute Episodic Story Lab will be held in Fall 2014 at the Sundance Resort in Sundance, Utah. Building on the Institute’s 30-year legacy of developing new work from storytellers with distinctive and risk-taking stories, this new initiative addresses the need for more opportunities for learning and mentorship of singular and diverse voices in scripted TV and online series. In collaboration with accomplished mentors, writers at the six-day, immersive Episodic Story Lab will work on developing stories and characters that play out over multiple episodes and will also have the opportunity to better understand the landscape for production and distribution of serialized stories. Both drama and comedy writing will be supported at the Lab, which has been organized under the leadership of Michelle Satter, Founding Director of the Institute’s Feature Film Program. The Lab is made possible by generous support and guidance from television producer Norman Lear and his wife, Institute Trustee Lyn Lear. The Institute cites the growth of great writing and bold content in recent years as inspiration for the Lab. -

Csflyer485 Sm

Sun Apr 15 THE BOLSHOI BALLET: GISELLE 12:55 Sun Apr 15 4:30, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed Apr 16 17 18 IN THE FADE 7:30 Thu Fri Apr 19 20 A FANTASTIC WOMAN 7:30 Sat Apr 21 2:30, 7:30 Sun Apr 22 THE SULTAN AND THE SAINT Special Screening 5:15 Sun Apr 22 2:30, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed Apr 23 24 25 HOSTILES 7:30 Thu Fri Apr 26 27 ANNIHILATION 7:30 Sat Apr 28 2:30, 7:30 General Admission $10 Sun Apr 29 2:30, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed Apr 30 May 1 2 THE PARTY 7:30 Friends of Cinestudio $7 Thu May 3 CLOSED FOR PRIVATE EVENT Senior Citizens (62+) $8 Students with valid ID Fri May 4 TRINITY FILM FESTIVAL presents DESIGN NIGHT OUT: SCREEN FREE ADMISSION 6:00 ® Ticket Prices for NTLive, Special Shows & Benefits vary Fri May 4 OSCAR NOMINATED LIVE ACTION SHORTS 8:30 Sat May 5 OSCAR® NOMINATED ANIMATED SHORTS 2:30 Cinestudio’s boxoffice is now online, so you can buy Sat May 5 TRINITY FILM FESTIVAL Doors open at 4:00, Festival begins at 5:00 tickets for any listed show at any time - online Sun May 6 2:30, 7:30 or at the boxoffice. We’re on Fandango too. Mon Tue Wed May 7 8 9 LEANING INTO THE WIND 7:30 DONATING TO CINESTUDIO? You can do that online or at the boxoffice, and now Thu May 10 NTLive: MACBETH LIVE from LONDON 2:00 100% of your donation comes to Cinestudio! Thu Fri May 10 11 LOVE, SIMON 7:30 Sat May 12 2:30, 7:30 Sun May 13 NTLive: MACBETH ENCORE from LONDON 1:00 Sun May 13 5:00, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed May 14 15 16 ISMAËL’S GHOSTS 7:30 Thu Fri May 17 18 BLACK PANTHER 7:30 Sat May 19 2:30, 7:30 Sun May 20 5:00, 7:30 Mon Tue Wed May 21 22 23 LOVELESS 7:30 Thu Fri May 24 25 ISLE -

10 Surprising Facts About Oscar Winner Ruth E. Carter and Her Designs

10 Surprising Facts About Oscar Winner Ruth E. Carter and Her Designs hollywoodreporter.com/lists/10-surprising-facts-oscar-winner-ruth-e-carter-her-designs-1191544 The Hollywood Reporter The Academy Award-winning costume designer for 'Black Panther' fashioned a headpiece out of a Pier 1 place mat, trimmed 150 blankets with a men's shaver, misspelled a word on Bill Nunn's famous 'Do the Right Thing' tee, was more convincing than Oprah and originally studied special education. Ruth E. Carter in an Oscars sweatshirt after her first nomination for "Malcolm X' and after her 2019 win for 'Black Panther.' Courtesy of Ruth E. Carter; Dan MacMedan/Getty Images Three-time best costume Oscar nominee Ruth E. Carter (whose career has spanned over 35 years and 40 films) brought in a well-deserved first win at the 91st Academy Awards on Feb. 24 for her Afrofuturistic designs in Ryan Coogler’s blockbuster film Black Panther. 1/10 Carter is the first black woman to win this award and was previously nominated for her work in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992) and Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997). "I have gone through so much to get here!” Carter told The Hollywood Reporter by email. “At times the movie industry can be pretty unkind. But it is about sticking with it, keeping a faith and growing as an artist. This award is for resilience and I have to say that feels wonderful!" To create over 700 costumes for Black Panther, Carter oversaw teams in Atlanta and Los Angeles, as well as shoppers in Africa. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

September/October 2014 at BFI Southbank

September/October 2014 at BFI Southbank Al Pacino in Conversation with Salome & Wilde Salome, Jim Jarmusch and Friends, Peter Lorre, Night Will Fall, The Wednesday Play at 50 and Fela Kuti Al Pacino’s Salomé and Wilde Salomé based on Oscar Wilde’s play, will screen at BFI Southbank on Sunday 21 September and followed by a Q&A with Academy Award winner Al Pacino and Academy Award nominee Jessica Chastain that will be broadcast live via satellite to cinemas across the UK and Ireland. This unique event will be hosted by Stephen Fry. Jim Jarmusch was one of the key filmmakers involved in the US indie scene that flourished from the mid-70s to the late 90s. He has succeeded in remaining true to the spirit of independence, with films such as Stranger Than Paradise (1984), Dead Man (1995) and, most recently, Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). With the re-release of Down By Law (1986) as a centrepiece for the season, we will also look at films that have inspired Jarmusch A Century of Chinese Cinema: New Directions will celebrate the sexy, provocative and daring work by acclaimed contemporary filmmakers such as Wong Kar-wai, Jia Zhangke, Wang Xiaoshuai and Tsai Ming-liang. These directors built on the innovations of the New Wave era and sparked a renewed global interest in Chinese cinema into the new millennium André Singer’s powerful new documentary Night Will Fall (2014) reveals for the first time the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps and the efforts made by army and newsreel cameramen to document the almost unbelievable scenes encountered there. -

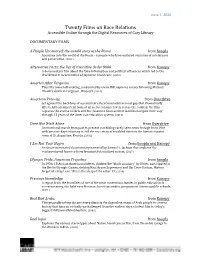

Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online Through the Digital Resources of Cary Library

June 1, 2020 Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online through the Digital Resources of Cary Library DOCUMENTARY FILMS A People Uncounted: the untold story of the Roma from hoopla A journey into the world of the Roma - a people who have endured centuries of intolerance and persecution. (2014) Alternative Facts: the lies of Executive Order 9066 from Kanopy A documentary film about the false information and political influences which led to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. (2018) America After Ferguson from Kanopy This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. (2014) American Promise from Overdrive Set against the backdrop of a persistent educational achievement gap that dramatically affects African-American boys at all socioeconomic levels across the country, the film captures the stories of Idris and his classmate Seun as their families navigate their way through 13 years of the American education system. (2013) Dare Not Walk Alone from Overdrive An emotional march from past to present combining rarely seen news footage from 1964 with present-day testimony to tell the true story of troubled times in the historic tourist town of St. Augustine, Florida. (2006) I Am Not Your Negro from hoopla and Kanopy An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson that explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. (2017) Olympic Pride, American Prejudice from hoopla In 1936, 18 African American athletes, dubbed the "black auxiliary" by Hitler, participated in the Berlin Olympic Games, defying Nazi Aryan Supremacy and Jim Crow Racism. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black ..................................