Art 8 Vol III Is 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

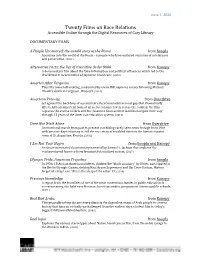

Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online Through the Digital Resources of Cary Library

June 1, 2020 Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online through the Digital Resources of Cary Library DOCUMENTARY FILMS A People Uncounted: the untold story of the Roma from hoopla A journey into the world of the Roma - a people who have endured centuries of intolerance and persecution. (2014) Alternative Facts: the lies of Executive Order 9066 from Kanopy A documentary film about the false information and political influences which led to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. (2018) America After Ferguson from Kanopy This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. (2014) American Promise from Overdrive Set against the backdrop of a persistent educational achievement gap that dramatically affects African-American boys at all socioeconomic levels across the country, the film captures the stories of Idris and his classmate Seun as their families navigate their way through 13 years of the American education system. (2013) Dare Not Walk Alone from Overdrive An emotional march from past to present combining rarely seen news footage from 1964 with present-day testimony to tell the true story of troubled times in the historic tourist town of St. Augustine, Florida. (2006) I Am Not Your Negro from hoopla and Kanopy An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson that explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. (2017) Olympic Pride, American Prejudice from hoopla In 1936, 18 African American athletes, dubbed the "black auxiliary" by Hitler, participated in the Berlin Olympic Games, defying Nazi Aryan Supremacy and Jim Crow Racism. -

Mario Van Peebles's <I>Panther</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Communication Studies Communication Studies, Department of 8-2007 Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Auburn University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Hoerl, Kristen, "Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party" (2007). Papers in Communication Studies. 196. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Communication Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Critical Studies in Media Communication 24:3 (August 2007), pp. 206–227; doi: 10.1080/07393180701520900 Copyright © 2007 National Communication Association; published by Routledge/Taylor & Francis. Used by permission. Published online August 15, 2007. Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Department of Communication and Journalism, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA Corresponding author – Kristen Hoerl, email [email protected] Abstract The 1995 movie Panther depicted the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense as a vibrant but ultimately doomed social movement for racial and economic justice during the late 1960s. Panther’s narrative indicted the white-operated police for perpetuating violence against African Americans and for un- dermining movements for black empowerment. -

Jeff Atmajian - Orchestration Credits

Jeff Atmajian - Orchestration Credits Feature Films: Directed By: Composer: Year: Distinctions: The Bucket List R. Reiner M. Shaiman 2007 The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep J. Russell J. N. Howard 2007 Hairspray A. Shankman M. Shaiman 2007 1408 M. Hafstrom G. Yared 2007 The Reaping S. Hopkins J. Frizzell 2007 Miss Potter C. Noonan R. Portman 2006 Blood Diamond E. Zwick J. N. Howard 2006 Angel F. Ozon P. Rombi 2006 My Super Ex Girlfriend I. Reitman T. Castelucci 2006 The Lady in the Water M. N. Shyamalan J. N. Howard 2006 The LakeHouse A. Agresti R. Portman 2006 King Kong P. Jackson J. N. Howard 2005 Golden Globe Nom. Infamous D. McGrath R. Portman 2005 Freedomland J. Roth J. N. Howard 2005 The Shaggy Dog B. Robbins A. Menken 2005 Rumor Has It R. Reiner M. Shaiman 2005 Oliver Twist R. Polanski R. Portman 2005 The Interpreter S. Pollack J. N. Howard 2005 Because of Winn Dixie W. Wang R. Portman 2004 Shall We Dance P. Chelsom G. Yared 2004 Collateral M. Mann J. N. Howard 2004 The Village M. N. Shyamalan J. N. Howard 2004 Oscar Nominee The Manchurian Candidate J. Demme R. Portman 2004 Troy (Unused) W. Peterson G. Yared 2004 The Passion of The Christ M. Gibson J. Debney 2004 Oscar Nominee Peter Pan P. J. Hogan J. N. Howard 2003 Big Fish T. Burton D. Elfman 2003 Oscar Nominee Mona Lisa Smile M. Newell R. Portman 2003 Hidalgo J. Johnston J. N. Howard 2003 Hulk A. Lee D. Elfman 2003 Alex and Emma R. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 02:14:10AM Via Free Access the Movie-Made Movement 121

6 The movie-made Movement: civil rites of passage Sharon Monteith Memory believes before knowing remembers. (William Faulkner) Forgetting is just another kind of remembering. (Robert Penn Warren) Film history cannibalises images, expropriates themes and tech- niques, and decants them into the contents of our collective memory. Movie memories are influenced by the (inter)textuality of media styles – Fredric Jameson has gone so far as to argue that such styles displace ‘real’ history. The Civil Rights Movement made real history but the Movement struggle was also a media event, played out as a teledrama in homes across the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and it is being replayed as a cinematic event. The interrela- tionship of popular memory and cinematic representations finds a telling case study in the civil rights era in the American South. This chapter assesses what films made after the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s express about the failure of the Movement to sus- tain and be sustained in its challenges to inequality and racist injus- tice. It argues that popular cultural currency relies on invoking images present in the sedimented layers of civil rights preoccupa- tions but that in the 1980s and 1990s movies also tap into ‘struc- tures of feeling’. Historical verisimilitude is bent to include what Tom Hayden called in 1962 ‘a reassertion of the personal’ as part of the political, but it is also bent to re-present the Movement as a communal struggle in which ordinary southern white people are much more significant actors in the personal and even the public space of civil rights politics than was actually the case. -

Racial Equity Resource Guide

RACIAL EQUITY RESOURCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 7 An Essay by Michael R. Wenger 17 Racial Equity/Racial Healing Tools Dialogue Guides and Resources Selected Papers, Booklets and Magazines Racial Equity Toolkits and Guides to Action Workshops, Convenings and Training Curricula 61 Anchor Organizations 67 Institutions Involved in Research on Structural Racism 83 National Organizing and Advocacy Organizations 123 Media Outreach Traditional Media Social Media 129 Recommended Articles, Books, Films, Videos and More Recommended Articles: Structural/Institutional Racism/Racial Healing Recommended Books Recommended Sources for Documentaries, Videos and Other Materials Recommended Racial Equity Videos, Narratives and Films New Orleans Focused Videos Justice/Incarceration Videos 149 Materials from WKKF Convenings 159 Feedback Form 161 Glossary of Terms for Racial Equity Work About the Preparer 174 Index of Organizations FOREWORD TO THE AMERICA HEALING COMMUNITY, When the W.K. Kellogg Foundation launched America Healing, we set for ourselves the task of building a community of practice for racial healing and equity. Based upon our firm belief that our greatest asset as a foundation is our network of grantees, we wanted to link together the many different organizations whose work we are now supporting as part of a broad collective to remove the racial barriers that limit opportunities for vulnerable children. Our intention is to ensure that our grantees and the broader community can connect with peers, expand their perceptions about possibilities for their work and deepen their understanding of key strategies and tactics in support of those efforts. In 2011, we worked to build this community We believe in a different path forward. -

Crossroads Film and Television Program List

Crossroads Film and Television Program List This resource list will help expand your programmatic options for the Crossroads exhibition. Work with your local library, schools, and daycare centers to introduce age-appropriate books that focus on themes featured in the exhibition. Help libraries and bookstores to host book clubs, discussion programs or other learning opportunities, or develop a display with books on the subject. This list is not exhaustive or even all encompassing – it will simply get you started. Rural themes appeared in feature-length films from the beginning of silent movies. The subject matter appealed to audiences, many of whom had relatives or direct experience with life in rural America. Historian Hal Barron explores rural melodrama in “Rural America on the Silent Screen,” Agricultural History 80 (Fall 2006), pp. 383-410. Over the decades, film and television series dramatized, romanticized, sensationalized, and even trivialized rural life, landscapes and experiences. Audiences remained loyal, tuning in to series syndicated on non-network channels. Rural themes still appear in films and series, and treatments of the subject matter range from realistic to sensational. FEATURE LENGTH FILMS The following films are listed alphabetically and by Crossroads exhibit theme. Each film can be a basis for discussions of topics relevant to your state or community. Selected films are those that critics found compelling and that remain accessible. Identity Bridges of Madison County (1995) In rural Iowa in 1965, Italian war-bride Francesca Johnson begins to question her future when National Geographic photographer Robert Kincaid pulls into her farm while her husband and children are away at the state fair, asking for directions to Roseman Bridge. -

WHAT I LEARNED at the MOVIES ABOUT LEGAL ETHICS and PROFESSIONALISM by Anita Modak-Truran

WHAT I LEARNED AT THE MOVIES ABOUT LEGAL ETHICS AND PROFESSIONALISM By Anita Modak-Truran HOW I GOT HERE I’ve been fortunate. I practice law. I make movies. I write about both. I took up my pen and started writing a film column for The Clarion-Ledger, a Gannett-owned newspaper, back in the late 90s, when I moved from Chicago, Illinois, to Jackson, Mississippi. (It was like a Johnny Cash song… “Yeah, I’m going to Jackson. Look out Jackson Town….”) I then turned my pen to writing for The Jackson Free Press, an indie weekly newspaper, which provided me opportunities to write about indie films and interesting people. I threw down the pen, as well as stopped my public radio movie reviews and the television segment I had for an ABC affiliate, when I moved three years ago from Jackson to Nashville to head Butler Snow’s Entertainment and Media Industry Group. During my journey weaving law and film together in a non-linear direction with no particular destination, I lived in the state where a young lawyer in the 1980s worked 60 to 70 hours a week at a small town law practice, squeezing in time before going to the office and during courtroom recesses to work on his first novel. John Grisham writes that he would not have written his first book if he had not been a lawyer. “I never dreamed of being a writer. I wrote only after witnessing a trial.” See http://www.jgrisham.com/bio/ (last accessed January 24, 2016). My law partners at Butler Snow have stories about the old days when Mr. -

Vibing with Blackness: Critical Considerations of Black Panther and Exceptional Black Positionings

arts Article Vibing with Blackness: Critical Considerations of Black Panther and Exceptional Black Positionings Derilene (Dee) Marco Media Studies Department, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2000, South Africa; [email protected] Received: 12 September 2018; Accepted: 15 November 2018; Published: 21 November 2018 Abstract: This article considers different ways in which Blackness is represented as exceptional in the 2018 film Black Panther. It also considers other iterations of Black visibility and legibility in the current popular culture context which appears to privilege Black narratives in interesting ways. The essay uses conceptual lenses from diaspora studies, Afro science fiction and Black feminist studies to critically engage the film and to critically question the notion of Black exceptionalism. Keywords: Afrofuturism; blackness; Black exceptionalism; cinema; post-apartheid; Black Panther film 1. Introduction How do you know I’m real? I’m not real. I come to you as myth, because that’s what black people are—myths. Ra(2017) Gabi Ngcobo holds the position as the first Black curator of the Berlin Biennale. In various articles from South African and other global publications, the overarching message about the Biennale was its (and its curator’s) exceptionalism. This exceptionalism, it seems, is to be read as a slightly nervous celebration of Ngcobo as Black and an equally anxious reception of her all black team and a host of seemingly ‘unknown artists’ who were on the show. Ngcobo herself confronts this geographical and psychological positional through the following—a position that I wish to use in this article as a basis and space for reflection: .. -

The Colored Pill: a History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 2020 The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines Wanda Lakota Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Wanda Lakota June 2020 Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Marie Calafell ©Copyright by Wanda Lakota 2020 All Rights Reserved Author: Wanda Lakota Title: The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Marie Calafell Degree Date: June 2020 ABSTRACT Of the 32 pharmaceuticals approved by the FDA in 2005, one medicine stood out. That medicine, BiDil®, was a heart failure medication that set a precedent for being the first approved race based drug for African Americans. Though BiDil®, was the first race specific medicine, racialized bodies have been used all throughout history to advance medical knowledge. The framework for race, history, and racialized drugs was so multi- tiered; it could not be conceptualized from a single perspective. For this reason, this study examines racialized medicine through performance, history, and discourse analysis. The focus of this work aimed to inform and build on a new foundation for social inquiry—using a history film performance to elevate knowledge about race based medicines. -

Night of the Living Dead: Reappraising an Undead Classic

Night of the living dead: reappraising an undead classic. Advertise Here Navigate to ... HO R R O R · 3 R EVIEWS Night of the Living Dead: Reappraising an Undead Classic Stephen Harper November 1, 2005 817 Romero’s canonical work remains timely decades later Introduction T here has been a veritable outbreak of zombie films in the last few years, from Hollywood blockbusters Resident Evil (Anderson, 2002) and Resident Evil 2: Apocalypse (Witt, 2004), to British films such as 28 Days Later (Boyle, 2002) and the zombie spoof Shaun of the Dead (Wrig ht, 2004). T he release in 2004 of Zack Snyder’s remake of Georg e A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) attests to the continuing influence and appeal of classic “zombie cinema.” While the cinematic concern with the undead predates Romero’s films, all of the recent films mentioned above have some connection to Romero (Romero was orig inally scheduled to write the screenplay for Resident Evil, for example, while the recent British films allude frequently to Romero’s work). T he following essay is an attempt to account for the continuing attraction of Romero’s first zombie film, Night of the Living Dead (1968), nearly forty years after its release. Shot in black-and-white over seven months on a shoestring budg et, Night of the Living Dead defined the modern horror movie and influenced a number of international horror directors, especially those working within the horror g enre. T he film’s plot of is simple: Barbra and her brother Johnny are attacked when visiting a g raveyard to honour the g rave of their father. -

Black Skin, White Gaze: the Presence and Function of the Linchpin Character in Biopics About Black American Protagonists

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Black Skin, White Gaze: The Presence and Function of the Linchpin Character in Biopics About Black American Protagonists Nicole N. Williams The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3856 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BLACK SKIN, WHITE GAZE: THE PRESENCE AND FUNCTION OF THE LINCHPIN CHARACTER IN BIOPICS ABOUT BLACK AMERICAN PROTAGONISTS by NICOLE N. WILLIAMS A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 ii © 2020 NICOLE N. WILLIAMS All Rights Reserved iii Black Skin, White Gaze: The Presence and Function of the Linchpin Character in Biopics About Black American Protagonists by Nicole N. Williams This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Juan Battle Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT Black Skin, White Gaze: The Presence and Function of the Linchpin Character in Biopics About Black American Protagonists by Nicole N. Williams Advisor: Juan Battle Throughout its existence the American film industry has--through the stories it has chosen to tell as well as discriminatory practices such as whitewashing and the erasure of non-White people-- enshrined whiteness as the default American racial identity. -

Ouagadougou '95 African Cinema

40 Acres And AMule Filmworks a OW ACCEPTING SCRIPTS © Copyright Required DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT • 8 ST. FELIX STREET • BROOKLYN, NY 11217 6 Close Up One in San Francisco and the other London. Two black women make J?1usic for the movies. 9 World View Ouagadougou '95: Mrican Cinema, Heart and Soul(d), Part I CLAIRE ANDRADE WATKINS In the first ofa two part article) Claire Andrade Watkins shares insights on the African Cinema scene from FESPACO. Black Film Review Volume 8, Number 3 12 Film Clips ]ezebel Filmworks does Hair. .. FILMFEST DC audience pick... VOices Corporate & Editorial Offices Against Violence. 2025 Eye Street, NW Suite 213 Washington, D.C. 20006 Tel. 202.466.2753 FEATURES Fax. 202.466.8395 e-mail 14 Hot Black Books Set Hollywood on Fire [email protected] TAREsSA STOVALL Editor-in-Chief Will the high sales ofblack novels translate into box office heat? Leasa Farrar-Frazer Consulting Editor 19 We Are the World: Black Film and the Globalization of Racism Tony Gittens (Black Film Institute, University of the District of CLARENCE LUSANE Columbia) What we need to know about who owns and controls the global images of Founding Editor black people. David Nicholson Art Direction & Design Lorenzo Wilkins for SHADOWORKS INTERVIEWS Contributing Editors TaRessa Stovall 22 APraise Poem: Filming the Life of Andre Lorde PAT AUFDERHEIDE Contributors Pat Aufderheide Producer Ada Gay Griffin shares her thoughts on the experience. Rhea Combs Eric Easter Joy Hunter 25 Live From The Madison Hotel Clarence Lusane Eric Easter talks with Carl Franklin) Walter Mosely and the Hughes Brothers Denise Maunder Marie Theodore Claire Andrade Watkins Co-Publisher DEPARTMENTS One Media, Inc.