The Colored Pill: a History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High- Percentage Plays

july / august 2009 / august july 39 FOR basketball enthusiasts everywhere enthusiasts basketball FOR FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE FIBA ASSIST assist don showalter post drills lionel hollins manuel trujillo vargas playing in transition high- giampiero ticchi 2-1-2 zone defense percentage cavelier-orlu the american way plays tables of contents 2009-10 FIBA CALENDAR COACHES 2009 FUNDAMENTALS AND YOUTH BASKETBALL 4 July 2009 Post Drills 02 - 12.07 FIBA U19 World by Don Showalter Championship for Men in Auckland (NZL) 23.07 -02.08 FIBA U19 World Championship for Women Playing in Transition 8 in Bangkok (THA) august 2009 by Manuel Trujillo Vargas 05 - 15.08 FIBA Africa Championship for Men in Libya (Benghazi and Tripoli) Attacking Zone Defenses 12 06 - 16.08 FIBA Asia Championship for Men in China, Tianjin by Kevin Sutton FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE City IS A PUBLICATION OF FIBA 23 - 25.08 FIBA Oceania International Basketball Federation Championship for Men in 51 – 53, Avenue Louis Casaï Sydney (AUS) and OFFENSE CH-1216 Cointrin/Geneva Switzerland Wellington (NZL) Tel. +41-22-545.0000, Fax +41-22-545.0099 26 - 06.09 FIBA Americas High-Percentage Plays 16 www.fiba.com / e-mail: [email protected] Championship for Men in Puerto Rico by Lionel Hollins IN COLLABORATION WITH Giganti del Basket, 31 - 02.09 FIBA Oceania Acacia Edizioni, Italy Championship for Women PARTNER in Wellington (NZL) and Canberra (AUS) WABC (World Association of Basketball DEFENSE Coaches), Dusan Ivkovic President september 2009 22 07 - 20.09 EuroBasket Men in Poland 2-1-2 Zone Defense (Gdansk, Poznan, Warsaw, by Giampiero Ticchi Editor-in-Chief Wroclaw, Bydgoszcz, Lodz Giorgio Gandolfi and Katowice) 17 - 24.09 FIBA Asia Championship for Women in Chennai, 28 India Difficulties for an American Player Editorial Office: Acacia Edizioni 23 - 27.09 FIBA Americas V. -

Medical Movies

Movies can provide you with a glimpse in to another world, explain a part of history and help you connect with patients. 28 Days (2000)- alcoholism and rehab 28 Days Later (2002) and 28 Weeks Later (2007)- escape of deadly virus A Beautiful Mind (2001)- a math genius suffers from schizophrenia A Mother’s Prayer (1995)- a mother plans for her son after she’s diagnosed with AIDS A Place for Annie (1994)- child with AIDS abandoned at birth A Private Matter (1992)- woman chooses to have an abortion after she finds out the fetus has severe problems Altered States (1980)- thriller about the research on altered states of consciousness Amnesia: The James Brighton Enigma (2005)- total loss of memory and its affects And The Band Played On (1993)- about the beginning of AIDS and the politics involved Article 99 (1992)- VA hospital with administration problems Awakenings (1990)- a new drug has coma patients waking up Boys on the Side (1995)- interactions regarding AIDS, homosexuality Bringing Out The Dead (1999)- burn out Britannia Hospital (1982)- psychiatric hospital that mirrors the downsides of Britain Carandiru (2003)- doctor initial arrives at a prison to study HIV but begins to see the people behind the infection Cider House Rules (1999)- a doctor of sorts deals with choosing to perform abortions or not City of Joy (1992)- working in the slums of Calcutta Clean and Sober (1988)- following a man who is dealing with cocaine addiction Coma (1978)- a doctor investigates why patients are showing up with brain damage after minor procedures Contagion (2011)- watch an epidemic unfold Dr. -

Searchers After Horror Understanding H

Mats Nyholm Mats Nyholm Searchers After Horror Understanding H. P. Lovecraft and His Fiction // Searchers After Horror Horror After Searchers // 2021 9 789517 659864 ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 Åbo Akademi University Press Tavastgatan 13, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. +358 (0)2 215 4793 E-mail: [email protected] Sales and distribution: Åbo Akademi University Library Domkyrkogatan 2–4, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. +358 (0)2 -215 4190 E-mail: [email protected] SEARCHERS AFTER HORROR Searchers After Horror Understanding H. P. Lovecraft and His Fiction Mats Nyholm Åbo Akademis förlag | Åbo Akademi University Press Åbo, Finland, 2021 CIP Cataloguing in Publication Nyholm, Mats. Searchers after horror : understanding H. P. Lovecraft and his fiction / Mats Nyholm. - Åbo : Åbo Akademi University Press, 2021. Diss.: Åbo Akademi University. ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 ISBN 978-951-765-987-1 (digital) Painosalama Oy Åbo 2021 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to investigate the life and work of H. P. Lovecraft in an attempt to understand his work by viewing it through the filter of his life. The approach is thus historical-biographical in nature, based in historical context and drawing on the entirety of Lovecraft’s non-fiction production in addition to his weird fiction, with the aim being to suggest some correctives to certain prevailing critical views on Lovecraft. These views include the “cosmic school” led by Joshi, the “racist school” inaugurated by Houellebecq, and the “pulp school” that tends to be dismissive of Lovecraft’s work on stylistic grounds, these being the most prevalent depictions of Lovecraft currently. -

Hurley Northstars

Call (906) 932-4449 Ironwood, MI Detroit basketball Griffin, Drummond lead Pistons Redsautosales.com to rout of Wizards 132-102 SPORTS • 7 Since 191 9 DAILY GLOBE Friday, December 27, 2019 Partly cloudy yourdailyglobe.com | High: 28 | Low: 22 | Details, page 2 RIDE THE ICE County may Pro Vintage consider economic snowmobile coordinator racing to begin By TOM LAVENTURE [email protected] By TOM LAVENTURE [email protected] BESSEMER – The Finance, Budgeting and Auditing Commit- IRONWOOD – The Ironwood tee of the Gogebic County Board Snowmobile Olympus will be of Commissioners on Thursday held over the next two weekends considered a possible economic with the oval ice racing at the recovery opportunity. Gogebic County Fairgrounds, During the committee meet- 648 West Cloverland Drive. ing prior to the full board meet- The Pro Vintage Racing will ing, the discussion focused on a be held this Saturday from 8 a.m. recommendation of the Michigan to 5 p.m. There are 39 vintage Economic Development Council class races that run the gamut of to hire a county economic recov- super stock, super modified, IFS ery coordinator. single track suspension and The idea was one solution other categories for older from meetings following the clo- machines. sure of the Ojibway Correctional The snowmobiles are pre- Facility, said Juliane Giackino, 1985 but many will run over 100 county administrator. The MEDC mph, said Jim Gribble, chairman would fund the position through of the Friends of the Gogebic a grant process of the U.S. County Fair, the nonprofit orga- Department of Agriculture. nization that organizes the Olym- Commissioner Joe Bonovetz pus. -

The Speed of the VCR

Edinburgh Research Explorer The speed of the VCR Citation for published version: Davis, G 2018, 'The speed of the VCR: Ti West's slow horror', Screen, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 41-58. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjy003 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/screen/hjy003 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Screen Publisher Rights Statement: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Screen following peer review. The version of record Glyn Davis; The speed of the VCR: Ti West’s slow horror, Screen, Volume 59, Issue 1, 1 March 2018, Pages 41–58 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjy003. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The speed of the VCR: Ti West’s slow horror GLYN DAVIS In Ti West’s horror film The House of the Devil (2009), Samantha (Jocelin Donahue), a college student short of cash, takes on a babysitting job. -

Desiring the Big Bad Blade: Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances

Desiring the Big Bad Blade: Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances Amira Jarmakani American Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4, December 2011, pp. 895-928 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/aq.2011.0061 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/aq/summary/v063/63.4.jarmakani.html Access provided by Georgia State University (4 Sep 2013 15:38 GMT) Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances | 895 Desiring the Big Bad Blade: Racing the Sheikh in Desert Romances Amira Jarmakani Cultural fantasy does not evade but confronts history. — Geraldine Heng, Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy n a relatively small but nevertheless significant subgenre of romance nov- els,1 one may encounter a seemingly unlikely object of erotic attachment, a sheikh, sultan, or desert prince hero who almost always couples with a I 2 white western woman. In the realm of mass-market romance novels, a boom- ing industry, the sheikh-hero of any standard desert romance is but one of the many possible alpha-male heroes, and while he is certainly not the most popular alpha-male hero in the contemporary market, he maintains a niche and even has a couple of blogs and an informative Web site devoted especially to him.3 Given popular perceptions of the Middle East as a threatening and oppressive place for women, it is perhaps not surprising that the heroine in a popular desert romance, Burning Love, characterizes her sheikh thusly: “Sharif was an Arab. To him every woman was a slave, including her. -

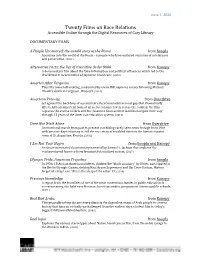

Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online Through the Digital Resources of Cary Library

June 1, 2020 Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online through the Digital Resources of Cary Library DOCUMENTARY FILMS A People Uncounted: the untold story of the Roma from hoopla A journey into the world of the Roma - a people who have endured centuries of intolerance and persecution. (2014) Alternative Facts: the lies of Executive Order 9066 from Kanopy A documentary film about the false information and political influences which led to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. (2018) America After Ferguson from Kanopy This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. (2014) American Promise from Overdrive Set against the backdrop of a persistent educational achievement gap that dramatically affects African-American boys at all socioeconomic levels across the country, the film captures the stories of Idris and his classmate Seun as their families navigate their way through 13 years of the American education system. (2013) Dare Not Walk Alone from Overdrive An emotional march from past to present combining rarely seen news footage from 1964 with present-day testimony to tell the true story of troubled times in the historic tourist town of St. Augustine, Florida. (2006) I Am Not Your Negro from hoopla and Kanopy An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson that explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. (2017) Olympic Pride, American Prejudice from hoopla In 1936, 18 African American athletes, dubbed the "black auxiliary" by Hitler, participated in the Berlin Olympic Games, defying Nazi Aryan Supremacy and Jim Crow Racism. -

Mario Van Peebles's <I>Panther</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Communication Studies Communication Studies, Department of 8-2007 Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Auburn University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Hoerl, Kristen, "Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party" (2007). Papers in Communication Studies. 196. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Communication Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Critical Studies in Media Communication 24:3 (August 2007), pp. 206–227; doi: 10.1080/07393180701520900 Copyright © 2007 National Communication Association; published by Routledge/Taylor & Francis. Used by permission. Published online August 15, 2007. Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Department of Communication and Journalism, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA Corresponding author – Kristen Hoerl, email [email protected] Abstract The 1995 movie Panther depicted the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense as a vibrant but ultimately doomed social movement for racial and economic justice during the late 1960s. Panther’s narrative indicted the white-operated police for perpetuating violence against African Americans and for un- dermining movements for black empowerment. -

Books, Films, and Medical Humanities

Books, Films, and Medical Humanities Films 50/50, 2011 Amour, 2012 And the Band Played On, 1993 Awakenings, 1990 Away From Her, 2006 A Beautiful Mind, 2001 The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, 2007 In The Family, 2011 The Intouchables, 2011 Iris, 2001 My Left Foot, 1989 One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975 Philadelphia, 1993 Rain Man, 1988 Silver Linings Playbook, 2012 The Station Agent, 2003 Temple Grandin, 2010 21 grams, 2003 Patch Adams, 1998 Wit, 2001 Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story, 2009 Awake, 2007 Something the Lord Made, 2004 Medicine Man, 1992 The Doctor, 1991 The Good Doctor, 2011 Side Effects, 2013 Books History/Biography Elmer, Peter and Ole Peter Grell, eds. Health, disease and society in Europe, 1500-1800: A Source Book. 2004. Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. 1963. 1 --Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. 1964. Gilman, Ernest B. Plague Writing in Early Modern England. 2009. Harris, Jonathan Gil. Foreign Bodies and the Body Politic: Discourses of Social Pathology in Early Modern England. 1998. Healy, Margaret. Fictions of Disease in Early Modern England: Bodies, Plagues and Politics. 2001. Lindemann, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. 1999. Markel, Howard. An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. 2011. Morris, David B. The Culture of Pain. 1991. Moss, Stephanie and Kaara Peterson, eds. Disease, Diagnosis and Cure on the Early Modern Stage. 2004. Mukherjee, Siddhartha. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. 2010. Newman, Karen. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Text Machines: Mnemotechnical Infrastructure as Exappropriation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3cj9797z Author McCoy, Jared Publication Date 2020 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Text Machines: Mnemotechnical Infrastructure as Exappropriation DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English by Jared McCoy Dissertation Committee: Professor Andrzej Warminski, Chair Professor Rajagopalan Radhakrishnan Professor Geoffrey Bowker 2020 © 2020 Jared McCoy Dedication TO MY PARENTS for their boundless love and patience …this requires a comprehensive reading of Heidegger that is hard, you know, to do quickly. Paul de Man ii Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................. iii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. v Curriculum Vitae ..................................................................................................................... vi Abstract of the Dissertation .................................................................................................... vii I. History of Inscription ........................................................................................................... -

Racial Equity Resource Guide

RACIAL EQUITY RESOURCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 7 An Essay by Michael R. Wenger 17 Racial Equity/Racial Healing Tools Dialogue Guides and Resources Selected Papers, Booklets and Magazines Racial Equity Toolkits and Guides to Action Workshops, Convenings and Training Curricula 61 Anchor Organizations 67 Institutions Involved in Research on Structural Racism 83 National Organizing and Advocacy Organizations 123 Media Outreach Traditional Media Social Media 129 Recommended Articles, Books, Films, Videos and More Recommended Articles: Structural/Institutional Racism/Racial Healing Recommended Books Recommended Sources for Documentaries, Videos and Other Materials Recommended Racial Equity Videos, Narratives and Films New Orleans Focused Videos Justice/Incarceration Videos 149 Materials from WKKF Convenings 159 Feedback Form 161 Glossary of Terms for Racial Equity Work About the Preparer 174 Index of Organizations FOREWORD TO THE AMERICA HEALING COMMUNITY, When the W.K. Kellogg Foundation launched America Healing, we set for ourselves the task of building a community of practice for racial healing and equity. Based upon our firm belief that our greatest asset as a foundation is our network of grantees, we wanted to link together the many different organizations whose work we are now supporting as part of a broad collective to remove the racial barriers that limit opportunities for vulnerable children. Our intention is to ensure that our grantees and the broader community can connect with peers, expand their perceptions about possibilities for their work and deepen their understanding of key strategies and tactics in support of those efforts. In 2011, we worked to build this community We believe in a different path forward.