UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catharsis and Salvation in the Mosaic of Casaranello (Italy, 6Th Century)

American Journal of Art and Design 2021; 6(3): 84-94 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajad doi: 10.11648/j.ajad.20210603.13 ISSN: 2578-7799 (Print); ISSN: 2578-7802 (Online) A Journey of the Soul: Catharsis and Salvation in the Mosaic of Casaranello (Italy, 6th Century) Francesco Danieli Gli Argonauti, Roman University Editions, Rome, Italy Email address: To cite this article: Francesco Danieli. A Journey of the Soul: Catharsis and Salvation in the Mosaic of Casaranello (Italy, 6th Century). American Journal of Art and Design . Vol. 6, No. 3, 2021, pp. 84-94. doi: 10.11648/j.ajad.20210603.13 Received : June 12, 2021; Accepted : July 19, 2021; Published : July 28, 2021 Abstract: The church of Santa Maria della Croce in Casaranello (Casarano, Italy, 6th century) is an important paleo- Byzantine testimony in Southern Italy. The building is well preserved and corresponds more or less to its original structure because in the late-medieval age the community of Casaranum decided to move the residential area up the hill overlooking the original hamlet. The German art historian Arthur Haseloff (1872-1955) visited the church in 1907, intrigued by a bibliographic indication by Wladimir De Gruneisen, and he found it in the miserable condition of stall for sheep and goats. When he entered the church, he immediately realised he was in front of one of the most important jewels of the paleochristian art: a treasure fallen into oblivion and whose value deserved to be highlighted. Haseloff summarily analysed the site of Casaranello, paying particular attention to the mosaic. This research promoted a new awareness towards Santa Maria della Croce and laid the basis for the restoration interventions carried out during the second half of the ‘900s. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

About: Plato an Entity of Type : Person, from Named Graph : Within Data Space : Dbpedia.Org

About: Plato An Entity of Type : person, from Named Graph : http://dbpedia.org, within Data Space : dbpedia.org Plato (/ˈpleɪtoʊ/; Greek: Πλάτων, Plátōn, "broad"; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BCE) was a philosopher, as well as mathematician, in Classical Greece. He is considered an essential figure in the development of philosophy, especially the Western tradition, and he founded the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with Socrates and his most famous student, Aristotle, Plato laid the foundations of Western philosophy and science. Property Value dbo:abstract Plato (/ˈpleɪtoʊ/; Greek: Πλάτων, Plátōn, "broad"; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BCE) was a philosopher, as well as mathematician, in Classical Greece. He is considered an essential figure in the development of philosophy, especially the Western tradition, and he founded the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with Socrates and his most famous student, Aristotle, Plato laid the foundations of Western philosophy and science. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."Plato's dialogues have been used to teach a range of subjects, including philosophy, logic, ethics, rhetoric, religion and mathematics. His lasting themes include Platonic love, the theory of forms, the five regimes, innate knowledge, among others. His theory of forms launched a unique perspective on abstract objects, and led to a school of thought called Platonism. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts. -

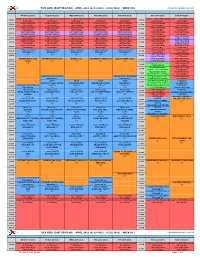

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof. -

Rohde's Theory of Relationship Between the Novel and Rhetoric

2020-3673-AJHA-LIT 1 Rohde’s Theory of Relationship Between the Novel and 2 Rhetoric and the Problem of Evaluating the Entire Post- 3 Classical Greek Literature 4 5 The one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the first publication of Rohde’s monograph 6 on the Greek novel is drawing near affording a welcome occasion for raising the big 7 question as to what remains of it today, all the more as the ancient novel, just due to his 8 classical work, has become a major area of research. The aforesaid monograph, 9 considered to be one of the greatest scientific achievements of the eighteenth century, 10 can be justifiably used as a litmus test for ascertaining how efficient methods hitherto 11 employed were or, in other words, whether we are entitled to speak of the continuous 12 progress in research or the opposite is true. Finally, the questions raised in the 13 monograph will turn out to be more important than the results obtained by the author, in 14 so far as the latter, based on his unfinished theses, proved to be very harmful to 15 evaluating both the Greek novel and the entire post-classical Greek literature. In this 16 paper we focus our attention on two major questions raised by the author such as 17 division of the third type of narration in the rhetorical manuals of the classical antiquity 18 and the nature of rhetoric, as expressed in the writings of the major exponents of the 19 Second Sophistic so as to be in a position to point to the way out of aporia, with the 20 preliminary remark that we shall not be able to get the full picture of the Greek novel 21 until the two remaining big questions posed by the author, such as the role played by 22 both Tyche and women in the Greek novel, are fully answered. -

Philosophy in Front of Religion

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 7 No.1 ISSN 2240-0524 January 2017 Research Article © 2017 Dorian Sevo. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Philosophy in Front of Religion Dorian Sevo Doi:10.5901/jesr.2017.v7n1p127 Abstract From Plato to Aristotle, from Augustine to Aquinas from Pascal to Freud and Heidegger the world and philosophical thought has continually interpreted the human nature, the source of morality and religion, specifically what we call (metaphysics). Man of antiquity, the medieval, modern and contemporary has his attitude towards the sacred. But what is happening with the man of our age, what relation does it have nowadays with the sacred, what is his attitude and what are the reasons for this relationship with the sacred. All the above are part of this scientific research paper. To give readers an overview of attitudes of philosophical thought of different times in front of the sacred, what are its meanings at different times and how is the attitude toward the sacred today. Descriptive analysis of the philosophical and religious issues. 1. Introduction 1.1 Ancients in front of afterlife Philosophy and Religion have had and will always have connection with each other. Philosophy is as metaphysical as Religion or Faith as we might otherwise know it. Since antiquity we see a connection of religion and philosophy. Orphic religion in antiquity did the separation of the body to the soul, typical of the Christian faith, but also of the Islam, which are monotheistic religions. -

The Colored Pill: a History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 2020 The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines Wanda Lakota Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Wanda Lakota June 2020 Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Marie Calafell ©Copyright by Wanda Lakota 2020 All Rights Reserved Author: Wanda Lakota Title: The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Marie Calafell Degree Date: June 2020 ABSTRACT Of the 32 pharmaceuticals approved by the FDA in 2005, one medicine stood out. That medicine, BiDil®, was a heart failure medication that set a precedent for being the first approved race based drug for African Americans. Though BiDil®, was the first race specific medicine, racialized bodies have been used all throughout history to advance medical knowledge. The framework for race, history, and racialized drugs was so multi- tiered; it could not be conceptualized from a single perspective. For this reason, this study examines racialized medicine through performance, history, and discourse analysis. The focus of this work aimed to inform and build on a new foundation for social inquiry—using a history film performance to elevate knowledge about race based medicines. -

Conjure One Extraordinary Ways Mp3, Flac, Wma

Conjure One Extraordinary Ways mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Extraordinary Ways Country: US Released: 2005 Style: Downtempo, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1194 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1627 mb WMA version RAR size: 1159 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 288 Other Formats: MP2 AA MIDI APE MOD WAV MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Endless Dream 1 4:30 Music By – Fulber*Programmed By [Additional] – Carmen RizzoVocals, Lyrics By – Jane Face The Music 2 4:35 Lyrics By – Wright*, Lacey*Music By – Fulber*Strings – Chris ElliottVocals – Tiff Lacey Pilgrimage 3 Music By – Fulber*Piano – Chris Elliott, Susann RichterStrings – Chris ElliottVocals – 6:48 Joanna Stevens, Leah Randi One Word 4 4:40 Keyboards – Jamie MuhoberacMusic By – Fulber*Vocals, Lyrics By – Jane I Believe 5 6:07 Music By, Lyrics By – Shelley*Vocals – Rhys Fulber Beyond Being 6 7:07 Music By – Fulber*Vocals – Leah Randi, Rhys Fulber Extraordinary Way 7 4:40 Keyboards – Chris ElliottMusic By – Elliott*, Fulber*Vocals, Lyrics By – Jane Dying Light 8 6:45 Music By – Stevens*, Fulber*Vocals – Joanna Stevens Forever Lost 9 4:46 Lyrics By – Holmes*Music By – Fulber*Vocals – Chemda* Into The Escape 10 4:15 Music By – Fulber*Vocals – Chemda* Companies, etc. Licensed From – Nettwerk Productions Phonographic Copyright (p) – Nettwerk Productions Copyright (c) – Nettwerk Productions Manufactured By – Nettwerk America LLC Marketed By – Nettwerk America LLC Pressed By – Cinram, Richmond, IN Credits Bass – Leah Randi (tracks: 1, 4, 8) Design – Olaf Heine Drums, Percussion –