Briefing Policies for Children In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1882. Congressional Record-Senate. 2509

1882. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 2509 zens of Maryland, .for the establishment of a light-house at Drum· Mr. HAMPTON presented a memorial of the city council of Charles Point Harbor, Calvert County, Maryland-to the Committee on Com ton, South Carolina., in favor of an appropriation for the completion merce. of the jetties in the harbor at that place; which was referred to the By Mr. .CRAPO: The petition of Franklin Crocker, forTelief-to Committee on Commerce. the Committee on Claims. He also presented a petition of inmates of the Soldiers' Home, of By Mr. DE MOTTE: The petition ofJolmE. Hopkinsand91 others, Washington, District of Columbia, ex-soldiers of the Mexican and citizens of Indiana, for legislation to regulate railway transporta Indian wars, praying for an amendment of section 48~0 of the Revised tion-to the Committee on Commerce. Statutes, so a-s to grant them an increase of pension; which was By :Mr. DEUSTER: Memorial of the Legislature of Wisconsin, . referred to the Committee on Military Affairs. asking the Government for a. cession of certain lands to be used for Mr. ROLLINS presented the petition of ex-Governor James .A. park }Jurposes-to the Committee on the Public Lands. Weston, Thomas J. Morgan, G. B. Chandler, Nathan Parker, and · Also, the petition of E . .Asherman & Co. and others, against the other citizens of Manchester, New Hampshire, praying for the pas pas a~e of the "free-leaf-tobacco" bill-to the Committee on Ways sage of the Lowell bill, establishing a uniform bankrupt law through and 1\ieans. -

Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America

Reading the Market Peter Knight Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Knight, Peter. Reading the Market: Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.47478. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/47478 [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 08:25 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reading the Market new studies in american intellectual and cultural history Jeffrey Sklansky, Series Editor Reading the Market Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America PETER KNIGHT Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore Open access edition supported by The University of Manchester Library. © 2016, 2021 Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2021 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Johns Hopkins Paperback edition, 2018 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as folllows: Names: Knight, Peter, 1968– author Title: Reading the market : genres of financial capitalism in gilded age America / Peter Knight. Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, [2016] | Series: New studies in American intellectual and cultural history | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015047643 | ISBN 9781421420608 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421420615 (electronic) | ISBN 1421420600 [hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421420619 (electronic) Subjects: LCSH: Finance—United States—History—19th century | Finance— United States—History—20th century. -

![Power. Sir T. Browne. Attract, Vt] Attracting](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8102/power-sir-t-browne-attract-vt-attracting-848102.webp)

Power. Sir T. Browne. Attract, Vt] Attracting

power. Sir T. Browne. Attract, v. t.] Attracting; drawing; attractive. The motion of the steel to its attrahent. Glanvill. 2. (Med.) A substance which, by irritating the surface, excites action in the part to which it is applied, as a blister, an epispastic, a sinapism. trap. See Trap (for taking game).] To entrap; to insnare. [Obs.] Grafton. trapping; to array. [Obs.] Shall your horse be attrapped . more richly? Holland. page 1 / 540 handle.] Frequent handling or touching. [Obs.] Jer. Taylor. Errors . attributable to carelessness. J.D. Hooker. We attribute nothing to God that hath any repugnancy or contradiction in it. Abp. Tillotson. The merit of service is seldom attributed to the true and exact performer. Shak. But mercy is above this sceptered away; . It is an attribute to God himself. Shak. 2. Reputation. [Poetic] Shak. 3. (Paint. & Sculp.) A conventional symbol of office, character, or identity, added to any particular figure; as, a club is the attribute of Hercules. 4. (Gram.) Quality, etc., denoted by an attributive; an attributive adjunct or adjective. 2. That which is ascribed or attributed. Milton. Effected by attrition of the inward stomach. Arbuthnot. 2. The state of being worn. Johnson. 3. (Theol.) Grief for sin arising only from fear of punishment or feelings of shame. See Contrition. page 2 / 540 Wallis. Chaucer. 1. To tune or put in tune; to make melodious; to adjust, as one sound or musical instrument to another; as, to attune the voice to a harp. 2. To arrange fitly; to make accordant. Wake to energy each social aim, Attuned spontaneous to the will of Jove. -

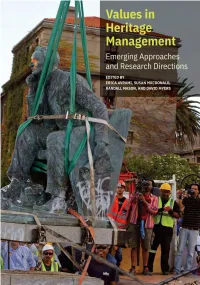

Values in Heritage Management

Values in Heritage Management Values in Heritage Management Emerging Approaches and Research Directions Edited by Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall Mason, and David Myers THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE, LOS ANGELES The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, John E. and Louise Bryson Director Jeanne Marie Teutonico, Associate Director, Programs The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) works internationally to advance conservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, field projects, and the dissemination of information. In all its endeavors, the GCI creates and delivers knowledge that contributes to the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage. © 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Values in heritage management (2017 : Getty Conservation Institute), author. | Avrami, Erica C., editor. | Getty Conservation Institute, The text of this work is licensed under a Creative issuing body, host institution, organizer. Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- Title: Values in heritage management : emerging NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a approaches and research directions / edited by copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons Erica Avrami, Susan Macdonald, Randall .org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. All images are Mason, and David Myers. reproduced with the permission of the rights Description: Los Angeles, California : The Getty holders acknowledged in captions and are Conservation Institute, [2019] | Includes expressly excluded from the CC BY-NC-ND license bibliographical references. covering the rest of this publication. These images Identifiers: LCCN 2019011992 (print) | LCCN may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or 2019013650 (ebook) | ISBN 9781606066201 manipulated without consent from the owners, (epub) | ISBN 9781606066188 (pbk.) who reserve all rights. -

Diasporas of Art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885–2014 Author(S): Debora L

Diasporas of Art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885–2014 Author(s): Debora L. Silverman Source: The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 87, No. 3 (September 2015), pp. 615-667 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/682912 . Accessed: 01/10/2015 20:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 164.67.16.55 on Thu, 1 Oct 2015 20:48:40 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Contemporary Issues in Historical Perspective Diasporas of Art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885–2014* Debora L. Silverman University of California, Los Angeles I. Introduction Challenges abound as contemporary museums engage the politics and culture of memory, particularly colonial memory, and ways of approaching histories of vio- lence. The South Africa Johannesburg Museum represents one end of a spectrum, with a stark, evocative new building obliging visitors to experience the spaces of apartheid. -

September 1933 Volume Xvii Published Quarterly Bythe

SEPTEMBER 1933 VOLUME XVII NUMBER 1 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BYTHE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN IMIIIIIMIiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiitllllllll^MlllllllIUIlllllllllllllllUlllllllllltllllllllllltMllllllllltllllllllllllllllHIIIIlllllllHIIIIIMIIII""!*!!*^ THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN is a state- aided corporation whose function is the cultivation and en- couragement of the historical interests of the State. To this end it invites your cooperation; membership is open to all, whether residents of Wisconsin or elsewhere. The dues of annual mem- i bers are three dollars, payable in advance; of life members, thirty dollars, payable once only. Subject to certain exceptions, mem- bers receive the publications of the Society, the cost of producing which far exceeds the membership fee. This is rendered possible by reason of the aid accorded the Society by the State. Of the r work and ideals of the Society this magazine affords, it is be- I lieved, a fair example. With limited means, much has already | I i been accomplished; with ampler funds more might be achieved. So far as is known, not a penny entrusted to the Society has ever i E been lost or misapplied. Property may be willed to the Society in entire confidence that any trust it assumes will be scrupulously | TiiiiinimiiiiiiHiiiiii| executedM. I I THE WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY is published quarterly by the Society, at 116 E. Main St., Evansville, Wisconsin, in September, Decem- ber, March, and June, and is distributed to its members and exchanges; others who so desire may receive it for the annual subscription of three dollars, payable in advance; single numbers may be had for seventy-five cents. -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. -

Organized Animal Protection and the Language of Rights in America, 1865-1900

*DO NOT CITE OR DISTRIBUTE WITHOUT PERMISSION* “The Inalienable Rights of the Beasts”1: Organized Animal Protection and the Language of Rights in America, 1865-1900 Susan J. Pearson Assistant Professor, Department of History Northwestern University Telephone: 847-471-3744 1881 Sheridan Road Email: [email protected] Evanston, IL 60208 ABSTRACT Contemporary animal rights activists and legal scholars routinely charge that state animal protection statutes were enacted, not to serve the interests of animals, but rather to serve the interests of human beings in preventing immoral behavior. In this telling, laws preventing cruelty to animals are neither based on, nor do they establish, anything like rights for animals. Their raison d’etre, rather, is social control of human actions, and their function is to efficiently regulate the use of property in animals. The (critical) contemporary interpretation of the intent and function of animal cruelty laws is based on the accretion of actions – on court cases and current enforcement norms. This approach confuses the application and function of anticruelty laws with their intent and obscures the connections between the historical animal welfare movement and contemporary animal rights activism. By returning to the context in which most state anticruelty statutes were enacted – in the nineteenth century – and by considering the discourse of those activists who promoted the original legislation, my research reveals a more complicated story. Far from being concerned only with controlling the behavior of deviants, the nineteenth-century animal welfare activists who agitated for such laws situated them within a “lay discourse” of rights, borrowed from the successful abolitionist movement, that connected animal sentience, proved through portrayals of their suffering, to animal rights. -

Diasporas of Art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885–2014

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Diasporas of art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the politics of memory in Belgium, 1885–2014 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4s25675m Journal Journal of Modern History, 87(3) ISSN 0022-2801 Author Silverman, DL Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.1086/682912 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Diasporas of Art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885–2014 Author(s): Debora L. Silverman Source: The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 87, No. 3 (September 2015), pp. 615-667 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/682912 . Accessed: 01/10/2015 20:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 164.67.16.55 on Thu, 1 Oct 2015 20:48:40 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Contemporary Issues in Historical Perspective Diasporas of Art: History, the Tervuren Royal Museum for Central Africa, and the Politics of Memory in Belgium, 1885–2014* Debora L. -

American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Brooklyn Office, Shelter, and Garage

DESIGNATION REPORT American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Brooklyn Office, Shelter, and Garage Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 515 Commission ASPCA Brooklyn Office, LP-2637 Shelter, and Garage October 29, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Brooklyn Office, Shelter, and Garage LOCATION Borough of Brooklyn 233 Butler Street (aka 231-237 Butler Street) LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE Designed by Renwick, Aspinwall and Tucker, the ASPCA’s finest surviving structure in New York City and the horse drinking fountain in front of it constitute an elegant reminder of the early promotion of humane treatment of animals, and New York’s central role in the national anticruelty movement. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 515 Commission ASPCA Brooklyn Office, LP-2637 Shelter, and Garage October 29, 2019 American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Annual Report for 1921 (New York: The Society, 1922), 21. LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, General Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Timothy Frye, Director of Special Projects and Diana Chapin Strategic Planning Wellington Chen Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Michael Devonshire Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Michael Goldblum John Gustafsson REPORT BY Anne Holford-Smith Michael Caratzas, Research Department Everardo Jefferson Jeanne Lutfy Adi Shamir-Baron EDITED BY Kate -

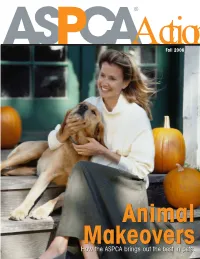

How the ASPCA Brings out the Best in Pets. How the ASPCA Brings out The

ActionFall 2006 Animal Makeovers How the ASPCA brings out the best in pets. >> PRESIDENT’S NOTE Building Humane Communities Board of Directors With autumn right around the corner, many of us are looking Officers of the Board forward with relief to bidding Hoyle C. Jones, Chairman, Linda Lloyd Lambert, Vice Chairman, Sally Spooner, Secretary, farewell to summer.This year, most James W. Gerard, Treasurer of the country experienced a summer of rising temperatures and Members of the Board gas prices. Here at the ASPCA headquarters in New Penelope Ayers, Alexandra G. Bishop, J. Elizabeth York City, things were no different.The rising cost of Bradham, Reenie Brown, Patricia J. Crawford, gasoline had curtailed the efforts of the Mayor’s Alliance Jonathan D. Farkas, Franklin Maisano, William Morrison Matthews, Sean McCarthy, to fuel a transport van that shuttles animals from city Gurdon H. Metz, Michael F.X. Murdoch, shelters to foster homes until the animals can be James L. Nederlander, Marsha Reines Perelman, adopted. Most of these animals would otherwise be George Stuart Perry, Helen S.C. Pilkington, Gail euthanized. Sanger, William Secord, Frederick Tanne, In an effort to salvage this program aimed at Richard C. Thompson, Cathy Wallach protecting the city’s homeless pets and our overall Directors Emeriti commitment to making New York City a model Steven M. Elkman, George Gowen, Alastair B. humane community, the ASPCA agreed to donate Martin, Thomas N. McCarter 3rd, Marvin Schiller, $10,000 to the Mayor’s Alliance to continue its James F. Stebbins, Esq. transportation initiative as fuel costs rise.The public stepped up and matched our donation, dollar-for-dollar. -

The Green-Wood Historic Fund Fall ’06: Welcome

FALL 2006 ›› GREEN-WOOD: NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK ›› ASPCA COMMEMORATES FOUNDER ›› SAVE OUR HISTORY ›› THE GREEN-WOOD HISTORIC FUND FALL ’06: WELCOME NOTES FROM THE GEM n September 27, 2006, Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne announced that The Green-Wood OCemetery would be the first cemetery in New York State and only the fourth in the nation to be designated a National Historic Landmark. Thanks to all those who ›› 2006 has been a magnificent year for books about perma- supported us in this endeavor, especially Senators nent residents of Green-Wood and we have tried to capital- Charles E. Schumer and Hillary Rodham Clinton; ize on all of them. Debby Applegate spoke to a full Historic Chapel crowd on her new book on Henry Ward Beecher and Congresswoman Nydia M. Velázquez; Mayor Michael R. we have lined up for later this year Robert C. Williams, who Bloomberg; President of the Borough of Brooklyn Marty will speak on his well-received book on Horace Greeley, and Markowitz; Landmarks Preservation Commissioner New York Times reporter James Barron, who will speak on Robert B. Tierney; Bernadette Castro, Commissioner of his book on the making of a Steinway Grand piano. Of course, all of these talks are followed by walks to the the NY State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic gravesites. The unheralded Green-Wood resident Charles Preservation; Kent Barwick, President of the Municipal Tyson Yerkes is the subject of a new book, Robber Baron by Art Society; Peg Breen, President of the New York John Franch, that received an excellent review in the Wall Landmarks Conservancy; Jay A.