The Churchill Chronicles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1882. Congressional Record-Senate. 2509

1882. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 2509 zens of Maryland, .for the establishment of a light-house at Drum· Mr. HAMPTON presented a memorial of the city council of Charles Point Harbor, Calvert County, Maryland-to the Committee on Com ton, South Carolina., in favor of an appropriation for the completion merce. of the jetties in the harbor at that place; which was referred to the By Mr. .CRAPO: The petition of Franklin Crocker, forTelief-to Committee on Commerce. the Committee on Claims. He also presented a petition of inmates of the Soldiers' Home, of By Mr. DE MOTTE: The petition ofJolmE. Hopkinsand91 others, Washington, District of Columbia, ex-soldiers of the Mexican and citizens of Indiana, for legislation to regulate railway transporta Indian wars, praying for an amendment of section 48~0 of the Revised tion-to the Committee on Commerce. Statutes, so a-s to grant them an increase of pension; which was By :Mr. DEUSTER: Memorial of the Legislature of Wisconsin, . referred to the Committee on Military Affairs. asking the Government for a. cession of certain lands to be used for Mr. ROLLINS presented the petition of ex-Governor James .A. park }Jurposes-to the Committee on the Public Lands. Weston, Thomas J. Morgan, G. B. Chandler, Nathan Parker, and · Also, the petition of E . .Asherman & Co. and others, against the other citizens of Manchester, New Hampshire, praying for the pas pas a~e of the "free-leaf-tobacco" bill-to the Committee on Ways sage of the Lowell bill, establishing a uniform bankrupt law through and 1\ieans. -

Briefing Policies for Children In

1 BROOKINGS INSTITUTION BROOKINGS-PRINCETON "FUTURE OF CHILDREN" BRIEFING POLICIES FOR CHILDREN IN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES INTRODUCTION, PRESENTATION, PANEL ONE AND Q&A SESSION Thursday, December 16, 2004 9:00 a.m.--11:00 a.m. Falk Auditorium The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM TAPE RECORDINGS.] 2 PANEL ONE: Moderator: RON HASKINS, Senior Fellow Economic Studies, Brookings Overview: DONALD HERNANDEZ, Professor of Sociology, University at Albany, SUNY MELVIN NEUFELD, Kansas State House of Representatives, Chairman, Kansas House Appropriations Committee RUSSELL PEARCE, Arizona State House of Representatives, Chairman, Arizona House Appropriations Committee FELIX ORTIZ, New York State Assembly 3 THIS IS AN UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT. P R O C E E D I N G S MR. HASKINS: Good morning. My name is Ron Haskins. I'm a senior fellow here at Brookings and also a senior consultant at the Annie Casey Foundation. I'd like to welcome you to today's session on children of immigrant families. The logic of the problem that we're dealing with here is straightforward enough, and I think it's pretty interesting for both people left and right of center. It turns out that we have a lot of children who live in immigrant families in the United States, and a large majority of them are already citizens, even if their parents are not. And again, a large majority of them will stay here for the rest of their life. So they are going to contribute greatly to the American economy for four or five decades, once they get to be 18 or 21, whatever the age might be. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

Oxfordshire. Chipping Nor Ton

DIRI::CTOR Y. J OXFORDSHIRE. CHIPPING NOR TON. 79 w the memory of Col. Henry Dawkins M.P. (d. r864), Wall Letter Box cleared at 11.25 a.m. & 7.40 p.m. and Emma, his wife, by their four children. The rents , week days only of the poor's allotment of so acres, awarded in 1770, are devoted to the purchase of clothes, linen, bedding, Elementary School (mixed), erected & opened 9 Sept. fuel, tools, medical or other aid in sickness, food or 1901 a.t a. cost of £ r,ooo, for 6o children ; average other articles in kind, and other charitable purposes; attendance, so; Mrs. Jackson, mistress; Miss Edith Wright's charity of £3 I2S. is for bread, and Miss Daw- Insall, assistant mistress kins' charity is given in money; both being disbursed by the vicar and churchwardens of Chipping Norton. .A.t Cold Norron was once an Augustinian priory, founded Over Norton House, the property of William G. Dawkina by William Fitzalan in the reign of Henry II. and esq. and now the residence of Capt. Denis St. George dedicated to 1818. Mary the Virgin, John the Daly, is a mansion in the Tudor style, rebuilt in I879, Evangelist and S. Giles. In the reign of Henry VII. and st'anding in a well-wooded park of about go acres. it was escheated to the Crown, and subsequently pur William G. Dawkins esq. is lord of the manor. The chased by William Sirlith, bishop of Lincoln (I496- area is 2,344 acres; rateable value, £2,oo6; the popula 1514), by-whom it was given to Brasenose College, Ox tion in 1901 was 3so. -

Year Books and Plea Rolls As Sources of Historical Information Author(S): H

Year Books and Plea Rolls as Sources of Historical Information Author(s): H. G. Richardson Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 5 (1922), pp. 28-70 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678457 Accessed: 27-06-2016 03:51 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press, Royal Historical Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society This content downloaded from 129.219.247.33 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 03:51:21 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms YEAR BOOKS AND PLEA ROLLS AS SOURCES OF HISTORICAL INFORMATION By H. G. RICHARDSON, M.A., B.Sc., F.R.HIST.S. Read December 8, 1921. EIGHTEEN years ago F. W. Maitland edited for the Selden Society the first volume of the Year Books of Edward II. In his introduction to that volume, moved by a pardonable enthusiasm, he wrote-perhaps not altogether advisedly- " It will some day seem a wonderful thing that men once thought that they could write the history of mediaeval England without using the Year Books." 1 Since then that sentence has been frequently repeated, although it is to be feared that for the most part historians have turned a deaf ear to its warning: and lately Mr. -

George Edmund Street

DOES YOUR CHURCH HAVE WORK BY ONE OF THE GREATEST VICTORIAN ARCHITECTS? George Edmund Street Diocesan Church Building Society, and moved to Wantage. The job involved checking designs submitted by other architects, and brought him commissions of his own. Also in 1850 he made his first visit to the Continent, touring Northern France. He later published important books on Gothic architecture in Italy and Spain. The Diocese of Oxford is extraordinarily fortunate to possess so much of his work In 1852 he moved to Oxford. Important commissions included Cuddesdon College, in 1853, and All Saints, Boyne Hill, Maidenhead, in 1854. In the next year Street moved to London, but he continued to check designs for the Oxford Diocesan Building Society, and to do extensive work in the Diocese, until his death in 1881. In Berkshire alone he worked on 34 churches, his contribution ranging from minor repairs to complete new buildings, and he built fifteen schools, eight parsonages, and one convent. The figures for Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire are similar. Street’s new churches are generally admired. They include both grand town churches, like All Saints, Boyne Hill, and SS Philip and James, Oxford (no longer in use for worship), and remarkable country churches such as Fawley and Brightwalton in Berkshire, Filkins and Milton- under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, and Westcott and New Bradwell in Buckinghamshire. There are still some people for whom Victorian church restoration is a matter for disapproval. Whatever one may think about Street’s treatment of post-medieval work, his handling of medieval churches was informed by both scholarship and taste, and it is George Edmund Street (1824–81) Above All Saints, Boyne His connection with the Diocese a substantial asset for any church to was beyond doubt one of the Hill, Maidenhead, originated in his being recommended have been restored by him. -

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS Except public holidays Effective from 02 August 2020 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, School 0840 1535 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0723 - 0933 33 1433 - 1633 1743 1843 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0730 0845 0940 40 1440 1540 1640 1750 1850 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0734 0849 0944 then 44 1444 1544 1644 1754 - Great Rollright 0658 0738 0853 0948 at 48 1448 1548 1648 1758 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0747 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1457 1557 1657 1807 - South Newington - - - - times - - - - - 1903 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0626 0716 0758 0911 1006 each 06 1506 1606 1706 1816 - Bloxham Church 0632 0721 0804 0916 1011 hour 11 1511 1611 1711 1821 1908 Banbury, Queensway 0638 0727 0811 0922 1017 17 1517 1617 1717 1827 1914 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0645 0735 0825 0930 1025 25 1525 1625 1725 1835 1921 SATURDAYS 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0838 0933 33 1733 1833 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0845 0940 40 1740 1840 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0849 0944 then 44 1744 - Great Rollright 0658 0853 0948 at 48 1748 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1757 - South Newington - - - times - - 1853 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0716 0911 1006 each 06 1806 - Bloxham Church 0721 0916 1011 hour 11 1811 1858 Banbury, Queensway 0727 0922 1017 17 1817 1904 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0735 0930 1025 25 1825 1911 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Bank Holidays At Easter, Christmas and New Year special timetables will run - please check www.stagecoachbus.com or look out for seasonal publicity This timetable is valid at the time it was downloaded from our website. -

Callow, Herbie

HERBERT (‘HERBIE’) CALLOW Herbie Callow, 81 years of age, is Deddington born and bred and educated in our village school; a senior citizen who has accepted the responsibilitiesoflife,hadfulfilmentinhiswork andovertheyearscontributedmuchtothe sporting acti vities of the village. Herecallsasalad,andlikeotheryouthsofhis agetakingpartintheworkinglifeofthevillage: upat6amtocollectandharnesshorsesforwork such as on Thursdays and Saturdays for Deely thecarrierhorses,pay1s.aweekandbreakfast, thenatnightfillingcoalbagsat2dpernight.At thattimecoalcametoAynhobybargeasdidthegraniteandstonechipsfor the roads. HespentashorttimeworkingattheBanburyIronworkingsandinSouthern IrelandwithvividmemoriesoftheSinnFinnriots.Helaterworkedfor OxfordshireCountyCouncilRoadDepartmentandreallythatwashisworking life.Intheearlydaystheroadsweremadeofslurriesinchipsandthenrolled bysteamroller,commentingthattheoddbanksatthesideofroadsweredue tothestintworkerscrapingmudofftheroads. DuringtheSecondWorldWarhewasamemberoftheAreaRescueTeam;the District Surveyor, Mr Rule, was in charge and Mr Morris was in charge of the HomeGuard. HerbiewasagangerontheOxfordby-passandrememberstheKidlington Zooandofthetimewhentwowolvesescaped.Helaterbecamegangforeman concernedwithbuildingbridges.Onehastorealiseatthatperiodthesmall andlargestreams,culvertsanddips,wereindividuallybridgedtocarryhorse -

FEBRUARY 2011 No: 244 CHAIRMANCHAIRMAN Chewingchewing Thethe Cudcud I Spent Three Days Last Week Sampling the Delights of the M25 in Rush Hour

FEBRUARY 2011 No: 244 CHAIRMANCHAIRMAN ChewingChewing thethe CudCud I spent three days last week sampling the delights of the M25 in rush hour. Now I know why I like living in North Aston. We live only about 50 miles from that dreaded FEBRUARY 2011, No: 244 stretch of road but it seems a million miles away. Useful Contacts You may not know it but we are classed as an isolated village North Aston News by Oxon County Council, because we have no shops or Telephone: (01869) 347356 services to offer the residents. When I first took over as Email: [email protected] chairman I said that I would love to see North Aston become Chris Tuffrey, Chairman Telephone: 07903 339155 a gated village. So why should we not go the whole hog and Email: [email protected] keep some of those 30,000 vehicles that pass through our Sue Hatzigeorgiou, Treasurer village away? If it were only possible! Telephone: (01869) 347727 Email: [email protected] The Village AGM was held a couple of weeks ago. It was Franca Potts, Secretary disappointing to see such a low turnout, not even 10% of the Telephone: (01869) 347356 Email: [email protected] village turning out. A list of new residents was posted in last North Aston PCC month’s edition of the News, so please come and join us at Clive Busby, Church Warden the next meeting and get involved in the village. Telephone: (01869) 338434 Email: [email protected] Several items came up at the meeting: Kildare Bourke-Borrowes, Churchwarden Telephone: (01869) 340200 Dial A Ride (Banbury Community Transport) Email: [email protected] After the item in the last Newsletter I have had North Aston Gardening Club correspondence with the BCT, who runs the service. -

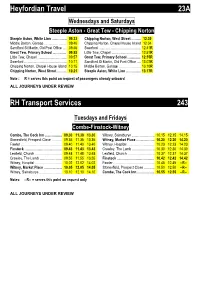

Timetables for Bus Services Under Review

Heyfordian Travel 23A Wednesdays and Saturdays Steeple Aston - Great Tew - Chipping Norton Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 09.33 Chipping Norton, West Street ……… 12.30 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 09.40 Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 12.34 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 09.46 Swerford ………………………………… 12.41R Great Tew, Primary School ………… 09.53 Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 12.51R Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 09.57 Great Tew, Primary School ………… 12.55R Swerford ………………………………… 10.11 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 13.02R Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 10.15 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 13.10R Chipping Norton, West Street ……... 10.21 Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 13.17R Note : R = serves this point on request of passengers already onboard ALL JOURNEYS UNDER REVIEW RH Transport Services 243 Tuesdays and Fridays Combe-Finstock-Witney Combe, The Cock Inn ………........ 09.30 11.30 13.30 Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.15 12.15 14.15 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 09.35 11.35 13.35 Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.20 12.20 14.20 Fawler ……………………………….. 09.40 11.40 13.40 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.23 12.23 14.23 Finstock ……………………………. 09.43 11.43 13.43 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 10.30 12.30 14.30 Leafield, Church ………………........ 09.48 11.48 13.48 Leafield, Church ………………........ 10.37 12.37 14.37 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 09.55 11.55 13.55 Finstock ……………………………. 10.42 12.42 14.42 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.02 12.02 14.02 Fawler ……………………………….. 10.45 12.45 --R-- Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.05 12.05 14.05 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 10.50 12.50 --R-- Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.10 12.10 14.10 Combe, The Cock Inn ………....... -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Romesrecruitsv8.Pdf

"ROME'S RECRUITS" a Hist of PROTESTANTS WHO HAVE BECOME CATHOLICS SINCE THE TRACTARIAN MOVEMENT. Re-printed, with numerous additions and corrections, from " J^HE ^HITEHALL j^EYIEW" Of September 28th, October 5th, 12th, and 19th, 1878. ->♦<- PUBLISHED AT THE OFFICE OF " THE WHITEHALL REVIEW." And Sold by James Parker & Co., 377, Strand, and at Oxford; and by Burns & Oates, Portman Street, W. 1878. PEEFACE. HE publication in four successive numbers of The Whitehall Review of the names of those Protestants who have become Catholics since the Tractarian move ment, led to the almost general suggestion that Rome's Recruits should be permanently embodied in a pamphlet. This has now been done. The lists which appeared in The Whitehall Review have been carefully revised, corrected, and considerably augmented ; and the result is the compilation of what must be regarded as the first List of Converts to Catholicism of a reliable nature. While the idea of issuing such a statement of" Perversions " or " Conversions " was received with unanimous favour — for the silly letter addressed to the Morning Post by Sir Edward Sullivan can only be regarded as the wild effusion of an ultra-Protestant gone very wrong — great curiosity has been manifested as to the sources from whence we derived our information. The modus operandi was very simple. Possessed of a considerable nucleus, our hands were strengthened immediately after the appearance of the first list by 071 XT PREFACE. the co-operation of nearly all the converts themselves, who hastened to beg the addition of their names to the muster-roll.