Chicago's Charter High Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chicago Engineers' Foundation of the Union League Club Honors 2013 Engineering Award Recipients

The Chicago Engineers' Foundation of the Union League Club Honors 2013 Engineering Award Recipients Chicago, IL – The Chicago Engineers’ Foundation announced the 2013 Incentive Education Awardees at it’s Annual Awards Dinner held at the Union League Club of Chicago on June 13, 2013. Over 200 guests were in attendance to honor and recognize the Award Recipients. The Keynote address for the evening was Dr. Don McNeeley, President and CEO of Chicago Tube and Iron Company (CTI), a U.S. based service center/fabricator, specializing in engineered applications. CTI is routinely involved in numerous domestic and international engineering projects. Awards totaling $91,300.00 were presented to 101 graduating high school seniors, university students continuing their collegiate engineering studies and college graduates who have received their degree in engineering. The Chicago Engineers Foundation of the Union League Club contributes to the civic and economic advancement of our community and country by encouraging and promoting the vital profession of engineering. The Engineers Foundation advances its mission primarily through its Incentive Education Awards, which are granted to graduates of Chicago high schools who are pursuing engineering degrees at a 4-year university. 2013 High School Graduates receiving Incentive Awards are listed below by their high school. 6 5 W. JACKSON BOULEVARDI CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 6 0 6 0 4 - 3 5 9 8 I 3 1 2 . 7 6 5 . 0 4 0 6 Benito Juarez High David Guan Hugo Lopez University of Illinois at Urbana- Illinois Institute of Technology Champaign Gwendolyn Brooks College Prep Nigel D. Haran Kierra Franklin University of Illinois at Urbana- Stanford University Champaign Gillespie Engineering Incentive Award Roger Mei Naim A. -

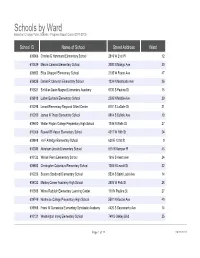

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

18-0124-Ex1 5

18-0124-EX1 5. Transfer from George Westinghouse High School to Education General - City Wide 20180046075 Rationale: FY17 School payment for the purchase of ventra cards between 2/1/2017 -6/30/2017 Transfer From: Transfer To: 53071 George Westinghouse High School 12670 Education General - City Wide 124 School Special Income Fund 124 School Special Income Fund 53405 Commodities - Supplies 57915 Miscellaneous - Contingent Projects 290003 Miscellaneous General Charges 600005 Special Income Fund 124 - Contingency 002239 Internal Accounts Book Transfers 002239 Internal Accounts Book Transfers Amount: $1,000 6. Transfer from Early College and Career - City Wide to Al Raby High School 20180046597 Rationale: Transfer funds for printing services. Transfer From: Transfer To: 13727 Early College and Career - City Wide 46471 Al Raby High School 369 Title I - School Improvement Carl Perkins 369 Title I - School Improvement Carl Perkins 54520 Services - Printing 54520 Services - Printing 212041 Guidance 212041 Guidance 322022 Career & Technical Educ. Improvement Grant (Ctei) 322022 Career & Technical Educ. Improvement Grant (Ctei) Fy18 Fy18 Amount: $1,000 7. Transfer from Facility Opers & Maint - City Wide to George Henry Corliss High School 20180046675 Rationale: CPS 7132510. FURNISH LABOR, MATERIALS & EQUIPMENT TO PERFORM A COMBUSTION ANALYSIS-CALIBRATE BURNER, REPLACE & TEST FOULED PARTS: FLAME ROD, WIRE, IGNITOR, CABLE, ETC... ON RTUs 18, 16, 14 & 20 Transfer From: Transfer To: 11880 Facility Opers & Maint - City Wide 46391 George Henry Corliss High School 230 Public Building Commission O & M 230 Public Building Commission O & M 56105 Services - Repair Contracts 56105 Services - Repair Contracts 254033 O&M South 254033 O&M South 000000 Default Value 000000 Default Value Amount: $1,000 8. -

Noble Street Charter School

NOBLE NETWORK OF CHARTER SCHOOLS, SUBSIDIARIES AND AFFILIATE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION YEARS ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 AND 2017 NOBLE NETWORK OF CHARTER SCHOOLS, SUBSIDIARIES AND AFFILIATE YEARS ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 AND 2017 CONTENTS Page Independent auditors’ report 1-2 Consolidated financial statements: Statements of financial position 3-4 Statements of activities 5-6 Statements of functional expenses 7 Statements of cash flows 8-10 Notes to financial statements 11-36 Supplemental financial schedules: Consolidating schedules of financial position 37-40 Consolidating schedules of activities 41-44 Consolidating schedules of functional expenses 45-46 Schedules of functional expenses: Noble Network Support Team (NNST) 47 Noble Street College Prep 48 Rauner College Prep 49 Pritzker College Prep 50 Rowe Clark College Prep 51 Golder College Prep 52 Gary Comer College Prep 53 UIC College Prep 54 Muchin College Prep 55 Chicago Bulls College Prep 56 Johnson College Prep 57 Hansberry College Prep 58 DRW College Prep 59 Baker College Prep 60 Butler College Prep 61 ITW David Speer Academy 62 The Noble Academy 63 NOBLE NETWORK OF CHARTER SCHOOLS, SUBSIDIARIES AND AFFILIATE YEARS ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 AND 2017 CONTENTS (CONTINUED) Page Supplemental financial schedules: (continued) Schedules of functional expenses: (continued) Mansueto High School 64 Noble Day Care 65 Noble Network Education Foundation 66 Schedules of Activities – Summer of a Lifetime, A Noble Network Program 67 Schedule of PCTC tuition 68 Independent Auditors’ -

Cta Student Ventra Card Distribution Schoools*

CTA STUDENT VENTRA CARD DISTRIBUTION SCHOOOLS* In addition to all Chicago Public Schools, the following schools may issue Student Ventra Cards only to their enrolled students: 1 Academy of Scholastic Achievement 38 Chicago International Charter Schools - 2 Ace Tech Charter High School Quest 3 Ada S. McKinley Lakeside Academy High 39 Chicago Jesuit Academy School 40 Chicago Math & Science Academy 4 Alain Locke Charter School 41 Chicago Talent Development High School 5 Alcuin Montessori School 42 Chicago Tech Academy 6 Amandla Charter School 43 Chicago Virtual Charter School 7 Argo Community High School 44 Chicago Waldorf School 8 ASN Preparatory Institute 45 Children Of Peace School 9 Aspira - Antonia Pantoja High School 46 Christ the King College Prep 10 Aspira - Early College High School 47 Christ the King Lutheran School 11 Aspira - Haugan Middle School 48 Community Christian Alternative Academy 12 Aspira Mirta Ramirez Computer Science High 49 Community School District 300 School 50 Community Youth Development Institute 13 Austin Career Education Center 51 Cornerstone Academy 14 Baker Demonstration School 52 Courtenay Elementary Language Arts 15 Banner Academy Center 16 Banner Learning School 53 Cristo Rey Jesuit High School 17 Betty Shabazz International Charter School 54 Delta/Summit Learning Center 18 Bloom Township High School - Dist 206 55 District 300 19 Brickton Montessori School 56 Dodge Renaissance Academy 20 Bronzeville Lighthouse Charter School 57 Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School 21 Brother Rice High School 58 Dwight D. -

Action Civics Showcase

16th annual Action Civics showcase Bridgeport MAY Art Center 10:30AM to 6:30PM 22 2018 DEMOCRACY IS A VERB WELCOME to the 16th annual Mikva Challenge ASPEN TRACK SCHOOLS Mason Elementary Action Civics Aspen Track Sullivan High School Northside College Prep showcase The Aspen Institute and Mikva Challenge have launched a partnership that brings the best of our Juarez Community Academy High School collective youth activism work together in a single This has been an exciting year for Action initiative: The Aspen Track of Mikva Challenge. Curie Metropolitan High School Civics in the city of Chicago. Together, Mikva and Aspen have empowered teams of Chicago high school students to design solutions to CCA Academy High School Association House Over 2,500 youth at some of the most critical issues in their communities. The result? Innovative, relevant, powerful youth-driven High School 70 Chicago high schools completed solutions to catalyze real-world action and impact. Phillips Academy over 100 youth action projects. High School We are delighted to welcome eleven youth teams to Jones College Prep In the pages to follow, you will find brief our Action Civics Showcase this morning to formally Hancock College Prep SCHEDULE descriptions of some of the amazing present their projects before a panel of distinguished Gage Park High School actions students have taken this year. The judges. Judges will evaluate presentations on a variety aspen track work you will see today proves once again of criteria and choose one team to win an all-expenses paid trip to Washington, DC in November to attend the inaugural National Youth Convening, where they will be competition that students not only have a diverse array able to share and learn with other youth leaders from around the country. -

VOISE Academy Pioneering a Blended-Learning Model in a Chicago Public High School

VOISE ACADEMY Pioneering a blended-learning model in a Chicago public high school A N E D U ca T I O N C ase S T U D Y James Sloan Visiting Research Fellow Katherine Mackey Research Fellow December 2009 | E-CS-003 NNOSIGHT www.innosightinstitute.org NSTITUTE Copyright © 2009 by Innosight Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. Innosight Institute, founded in May 2007, is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit think tank whose mission is to apply Harvard Business School Professor Clayton Christensen’s theories of disruptive innovation to develop and promote solutions to the most vexing problems in the social sector. Innosight Institute’s case studies are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent an endorsement by Innosight Institute. EXECUTive SUMMARY n the fall of 2008, a new high school located in the poverty-stricken, crime-ridden neighbor- hood of Austin on Chicago’s West Side opened its doors to 151 freshmen. Called VOISE IAcademy (VOISE), this school was different from many of the new high schools opening in Chicago at that time, as it blended a traditional brick-and-mortar school environment with something much less familiar—a fully online curriculum. Now in its second year of operations, VOISE, which stands for Virtual Opportunities Inside a School Environment, plans to add a new grade each year until it serves up to 600 students in grades 9 through 12. Autonomy VOISE was created under CPS’s Renaissance 2010 initiative, whose goal was to create 100 high- performing public schools in priority communities1 by the year 2010. -

A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago As Seen in the Naming of Schools

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1990 A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago as Seen in the Naming of Schools Mary McFarland-McPherson Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation McFarland-McPherson, Mary, "A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago as Seen in the Naming of Schools" (1990). Dissertations. 2709. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2709 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1990 Mary McFarland-McPherson A SOCIO-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF PUBLIC EDUCATION IN CHICAGO AS SEEN IN THE NAMING OF SCHOOLS by Mary McFarland-McPherson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 1990 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer sincerely appreciates the patience, · endurance and assistance afforded by the many persons who extended their unselfish support of this dissertation. Special orchids to Dr. Joan K. Smith for her untiring guidance, encouragement, expertise, and directorship. Gratitude is extended to Dr. Gerald L. Gutek and Rev. F. Michael Perko, S.J. who, as members of this committee provided invaluable personal and professional help and advice. The writer is thankful for the words of wisdom and assistance provided by: Mr. -

State of the Arts Report Draws Many District-Level Conclusions; the Data Behind These Conclusions Are Equally Powerful When Examined at the School Level

STATE OF THE ARTS IN CHICAGO PUBLIC SCHOOLS PROGRESS REPORT | 2016–17 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 6 CREATIVE SCHOOLS SURVEY PARTICIPATION 16 THE ARTS IN CHICAGO PUBLIC SCHOOLS 20 • Creative Schools Certification 21 • Staffing 30 • Instructional Minutes and Access 38 • Disciplines and Depth 42 • Arts Assets in Schools 45 • Arts Discipline Offerings 48 COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS 50 FUNDING 58 CPS ARTS EDUCATION PLAN PROGRESS 64 CONCLUSION 70 APPENDIX 72 • References 73 • Data Notes 74 • Glossary 76 CREATIVE SCHOOLS CERTIFICATION RUBRIC 80 INGENUITY | STATE OF THE ARTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE The 2016–17 State of the Arts in Chicago Public Schools (CPS) Progress Report highlights the progress CPS and Chicago’s arts SUMMARY education community are making toward fulfilling the goal— and the promise to CPS students—articulated in the 2012 CPS Arts Education Plan: that the arts should be brought to every child, in every grade, in every school. This year, as in each year since the Arts Education Plan was released, the progress report identifies some important gains. Foremost among these is that a higher percentage of CPS schools than ever before, serving a higher share of CPS students than ever before, are meeting the criteria to be rated as Strong or Excelling in the arts. This achievement is particularly encouraging considering the financial challenges the district has faced in recent years. Despite a frequently uncertain and challenging financial climate, and with additional arts gains clearly needed, data reflect that both the district and principals have continued to prioritize arts education in their schools. -

Noble Network of Charter Schools Reclutamiento De Diversidad Programa De Residencia Para Maestros

Noble Network of Charter Schools Reclutamiento de Diversidad Programa de Residencia para Maestros Noble-Relay Edgar Rios Reclutador de Diversidad Noble Network of Charter Schools Chicago, IL [email protected] Escuelas • Baker College Prep • Butler College Prep • Chicago Bulls College Prep • DRW College Prep • Gary Comer College Prep • Gary Comer College Prep Middle School • Golder College Prep • Hansberry College Prep • ITW David Speer Academy • Johnson College Prep • Mansueto High School • Muchin College Prep • The Noble Academy • Noble Street College Prep • Pritzker College Prep • Rauner College Prep • Rowe-Clark Math and Science Academy • UIC College Prep Page 1 Una Solución Probada Noble fue fundada por dos maestros de las escuelas públicas de Chicago y es la red de escuelas de inscripción abierta con más alto rendimiento • Fundada en 1999 • 17 escuelas • 12,000 estudiantes • 8,300 alumnos • 91% inscripción en la universidad • 81% estudiantes universitarios de primera generación Page 2 Cambiando Vidas Noble está haciendo accesso a la universidad una realidad para estudiantes de bajos recursos en porcentajes que sobrepasan los promedios del distrito escolar y la nación. 100% 91% 90% 11% 80% 70% 60% 56% 50% 20% 80% 40% 30% 52% 20% 36% 10% National Low- CPS Noble Income * 4yr 2yr * Numero de “National Low-Income” incluye la inscripcion en escuelas de 2 y 4 años Fuentes: Bajo Ingreso Nacional - Departamento de Estado de Educación de Educación de EE.UU., 2011,Números Nacionales son escuelas de 2 y 4 años combinadas; CPS - Oficina de Preparación Universitaria y Profesional, Clase del 2011; Noble Clase del 2013 – Centro Nacional de Informacion y seguimiento interno Page 3 Reclutamiento de Diversidad • 98% de nuestros estudiantes son Latinos o Afromericanos • Noble, esta tratando de añadir diversidad a su personal mediante la contratación de maestros pertenecientes a minorias. -

For Immediate Release: Contact: Jennifer Jones April 12, 2021 [email protected]

Governing Board Amanda Amert David Nadig Dr. Toinette Gunn Daniel Clary Johnni Rodgers Executive Director Rachel Haig Cindy Stuyvesant John Hammond Onur Surgit Tony Howard Aneesh Sohoni Eli Kay-Oliphant Chris Wheat Femi Masha Tania White For Immediate Release: Contact: Jennifer Jones April 12, 2021 [email protected] Hundreds of CPS High School Students Compete in City Championship Debate Tournament Chicago Debates wrapped its 2020-2021 high school debate season with its virtual City Championship Tournament this past weekend. The City Championship was the culminating event of the season, which brought together nearly 200 high school students from 26 Chicago Public Schools, all vying for the title of 2021 High School Debate Champion. In teams of two, students debated the topic of Criminal Justice Reform: The United States federal government should enact substantial criminal justice reform in the United States in one or more of the following areas: forensic science, policing, sentencing. Chicago Debates presented Gregorio Chavez of Pritzker College Prep with the 2021 Debater of the Year Award and Ryan Howell from Von Steuben Metropolitan Science Center as the 2021 Coach of the Year. Chicago Debates Associate Board member and recently appointed Cook County Public Defender, Sharone Mitchell, was also recognized as Chicago Debates’ Alum of the Year (Morgan Park, Class of 2001). Sharone credits the power of debate for much of his success: "I think Chicago Debates is a great engine of social change because we are building up the leaders of our city. We're putting them on a path to change the world. I have this incredible debt of gratitude to this program, to this activity. -

Certificate of Income Verification

Chicago Summer Business Institute Preparing Today’s Students to Become Tomorrow’s Professionals January 31, 2012 Dear School Administrator, It’s that time of the year again! This year represents the 22nd anniversary of the Chicago Summer Business Institute (“CSBI”). The CSBI program is sponsored by businesses throughout Chicago and is designed to introduce Chicago high school students to the business industry through a meaningful work experience, as well as seminars. Since its inception, the CSBI program has helped numerous Chicago high school students expand their horizons and experience the excitement and boundless opportunities available to them through a paid summer internship in the city’s business and legal communities. We need your help in making this program available to students who are currently sophomores and juniors of your high school. Enclosed are brochures, applications and Certificate of Income Verification forms to be photocopied and distributed to your sophomore and junior students who meet the eligibility requirements and are interested in participating in this program. APPLICATIONS CANNOT BE COMPLETED ONLINE. All completed material must be received or postmarked on or before March 30, 2012 at the following address: Chicago Summer Business Institute P.O. Box 64445 Chicago, Illinois 60664 Additionally, Munity | Chicago, an affiliate of CSBI, will host a free Job Readiness Workshop for CSBI applicants on Saturday, March 24, 2012 from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Workshop highlights include creating effective resumes, preparing for successful interviews, making positive first impressions, understanding office etiquette, and interactive role-playing. The attached flyer should be photocopied and distributed to your students along with the above- mentioned application material.