Criss-Cross Heart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate

Neonatal Nursing Education Brief: How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate https://www.seattlechildrens.org/healthcare- professionals/education/continuing-medical-nursing-education/neonatal- nursing-education-briefs/ Cardiac defects are commonly seen and are the leading cause of death in the neonate. Prompt suspicion and recognition of congenital heart defects can improve outcomes. An ECHO is not needed to make a diagnosis. Cardiac defects, congenital heart defects, NICU, cardiac assessment How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate Purpose and Goal: CNEP # 2092 • Understand the signs of congenital heart defects in the neonate. • Learn to recognize and detect heart defects in the neonate. None of the planners, faculty or content specialists has any conflict of interest or will be presenting any off-label product use. This presentation has no commercial support or sponsorship, nor is it co-sponsored. Requirements for successful completion: • Successfully complete the post-test • Complete the evaluation form Date • December 2018 – December 2020 Learning Objectives • Describe the risk factors for congenital heart defects. • Describe the clinical features of suspected heart defects. • Identify 2 approaches for recognizing congenital heart defects. Introduction • Congenital heart defects may be seen at birth • They are the most common congenital defect • They are the leading cause of neonatal death • Many neonates present with symptoms at birth • Some may present after discharge • Early recognition of CHD -

Congenital Cardiac Surgery ICD9 to ICD10 Crosswalks Page 1 of 4 8

Congenital Cardiac Surgery ICD9 to ICD10 Crosswalks ICD-9 code ICD-9 Descriptor ICD-10 Code ICD-10 Descriptor 164.1 Malignant neoplasm of heart C38.0 Malignant neoplasm of heart 164.1 Malignant neoplasm of heart C45.2 Mesothelioma of pericardium 212.7 Benign neoplasm of heart D15.1 Benign neoplasm of heart 425.11 Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy I42.1 Obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 425.18 Other hypertrophic cardiomyopathy I42.2 Other hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 425.3 Endocardial fibroelastosis I42.4 Endocardial fibroelastosis 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.0 Dilated cardiomyopathy 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.5 Other restrictive cardiomyopathy 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.8 Other cardiomyopathies 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.9 Cardiomyopathy, unspecified 426.9 Conduction disorder, unspecified I45.9 Conduction disorder, unspecified 745.0 Common truncus Q20.0 Common arterial trunk 745.10 Complete transposition of great vessels Q20.3 Discordant ventriculoarterial connection 745.11 Double outlet right ventricle Q20.1 Double outlet right ventricle 745.12 Corrected transposition of great vessels Q20.5 Discordant atrioventricular connection 745.19 Other transposition of great vessels Q20.2 Double outlet left ventricle 745.19 Other transposition of great vessels Q20.3 Discordant ventriculoarterial connection 745.19 Other transposition of great vessels Q20.8 Other congenital malformations of cardiac chambers and connections 745.2 Tetralogy of fallot Q21.3 Tetralogy of Fallot 745.3 Common -

Congenital Cardiovascular Defects

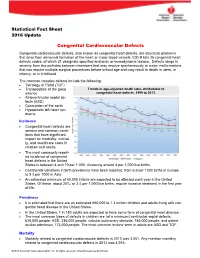

Statistical Fact Sheet 2016 Update Congenital Cardiovascular Defects Congenital cardiovascular defects, also known as congenital heart defects, are structural problems that arise from abnormal formation of the heart or major blood vessels. ICD-9 lists 25 congenital heart defects codes, of which 21 designate specified anatomic or hemodynamic lesions. Defects range in severity from tiny pinholes between chambers that may resolve spontaneously to major malformations that can require multiple surgical procedures before school age and may result in death in utero, in infancy, or in childhood. The common complex defects include the following: Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) Transposition of the great Trends in age-adjusted death rates attributable to arteries congenital heart defects, 1999 to 2013. Atrioventricular septal de- fects (ASD) Coarctation of the aorta Hypoplastic left heart syn- drome Incidence Congenital heart defects are serious and common condi- tions that have significant impact on morbidity, mortali- ty, and healthcare costs in children and adults. The most commonly report- ed incidence of congenital heart defects in the United States is between 4 and 10 per 1,000, clustering around 8 per 1,000 live births. Continental variations in birth prevalence have been reported, from 6.9 per 1000 births in Europe to 9.3 per 1000 in Asia. An estimated minimum of 40,000 infants are expected to be affected each year in the United States. Of these, about 25%, or 2.4 per 1,000 live births, require invasive treatment in the first year of life. Prevalence It is estimated that there are an estimated 650,000 to 1.3 million children and adults living with con- genital heart disease in the United States. -

A Human Laterality Disorder Associated with a Homozygous WDR16 Deletion

European Journal of Human Genetics (2015) 23, 1262–1265 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/15 www.nature.com/ejhg SHORT REPORT A human laterality disorder associated with a homozygous WDR16 deletion Asaf Ta-Shma*,1,3, Zeev Perles1,3, Barak Yaacov2, Marion Werner2, Ayala Frumkin2, Azaria JJT Rein1 and Orly Elpeleg2 The laterality in the embryo is determined by left-right asymmetric gene expression driven by the flow of extraembryonic fluid, which is maintained by the rotary movement of monocilia on the nodal cells. Defects manifest by abnormal formation and arrangement of visceral organs. The genetic etiology of defects not associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia is largely unknown. In this study, we investigated the cause of situs anomalies, including heterotaxy syndrome and situs inversus totalis, in a consanguineous family. Whole-exome analysis revealed a homozygous deleterious deletion in the WDR16 gene, which segregated with the phenotype. WDR16 protein was previously proposed to play a role in cilia-related signal transduction processes; the rat Wdr16 protein was shown to be confined to cilia-possessing tissues and severe hydrocephalus was observed in the wdr16 gene knockdown zebrafish. The phenotype associated with the homozygous deletion in our patients suggests a role for WDR16 in human laterality patterning. Exome analysis is a valuable tool for molecular investigation even in cases of large deletions. European Journal of Human Genetics (2015) 23, 1262–1265; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.265; published online 3 December 2014 INTRODUCTION and development, followed till 7 years, were normal. Her younger brother, Visceral asymmetry is determined through embryonic ciliary motion, patient II-4, was brought to medical attention at 7 weeks of age because of viral and normal function of the motile cilia plays a key role in the bronchiolitis. -

Isolated Levocardia with Situs Inversus Without Cardiac Abnormality in Fetus: Prenatal Diagnosis and Management

A L J O A T U N R I N R A E L P Case Report P L E R A Perinatal Journal 2020;28(1):48–51 I N N R A U T A L J O ©2020 Perinatal Medicine Foundation Isolated levocardia with situs inversus without cardiac abnormality in fetus: prenatal diagnosis and management Mucize Eriç ÖzdemirİD , Oya Demirci İD Department of Perinatology, Zeynep Kamil Maternity and Children’s Diseases Training and Research Hospital., Health Sciences University, Istanbul, Turkey Abstract Özet: Kardiyak anomalisi olmayan fetüste situs inversuslu izole levokardi: Prenatal tan› ve yönetim Objective: Isolated levocardia is a situs abnormality that the heart is Amaç: ‹zole levokardi, kalbin normal levo pozisyonunda oldu¤u in the normal levo position, but the abdominal viscera are in dextro fakat abdominal iç organlar›n dekstro pozisyonunda oldu¤u bir si- position. Most cases are accompanied by structural heart anomalies. tus anomalisidir. Ço¤u olguda yap›sal kalp anomalileri de efllik et- In this case, we aimed to present a fetus with isolated levocardia with- mektedir. Çal›flmam›zda, kardiyak anomalisi olmayan izole levo- out cardiac abnormality. kardili bir fetüsü sunmay› amaçlad›k. Case: The mother was referred to our clinic with a suspicion of fetal Olgu: Olgumuz, 22. gebelik haftas›nda fetal dekstrokardi flüphe- dextrocardia at 22 weeks of gestation. When detailed examination was siyle klini¤imize sevk edildi. Planlanan detayl› ultrason muayene- planned by ultrasonography isolated levocardia was detected in fetus. sinde, fetüste izole levokardi tespit edildi. Fetal ekokardiyografide There were no cardiac abnormalities in fetal echocardiography. Fetus hiçbir kardiyak anomali görülmedi. -

Factors Impacting Echocardiographic Imaging After the Fontan Procedure: a Report from the Pediatric Heart Network Fontan Cross- Sectional Study

Children's Mercy Kansas City SHARE @ Children's Mercy Manuscripts, Articles, Book Chapters and Other Papers 10-1-2013 Factors impacting echocardiographic imaging after the Fontan procedure: a report from the pediatric heart network fontan cross- sectional study. Richard V. Williams Renee Margossian Minmin Lu Andrew M. Atz Timothy J. Bradley See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlyexchange.childrensmercy.org/papers Part of the Cardiology Commons, Cardiovascular System Commons, Congenital, Hereditary, and Neonatal Diseases and Abnormalities Commons, Pediatrics Commons, and the Surgical Procedures, Operative Commons Recommended Citation Williams, R. V., Margossian, R., Lu, M., Atz, A. M., Bradley, T. J., Campbell, M. J., Colan, S. D., Gallagher, D., Lai, W. W., Pearson, G. D., Prakash, A., Shirali, G. S., Cohen, M. S., . Factors impacting echocardiographic imaging after the Fontan procedure: a report from the pediatric heart network fontan cross-sectional study. Echocardiography (Mount Kisco, N.Y.) 30, 1098-1106 (2013). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SHARE @ Children's Mercy. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscripts, Articles, Book Chapters and Other Papers by an authorized administrator of SHARE @ Children's Mercy. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Creator(s) Richard V. Williams, Renee Margossian, Minmin Lu, Andrew M. Atz, Timothy J. Bradley, Michael Jay Campbell, Steven D. Colan, Dianne Gallagher, Wyman W. Lai, Gail D. Pearson, Ashwin Prakash, Girish S. Shirali, Meryl S. Cohen, and Pediatric Heart Network Investigators This article is available at SHARE @ Children's Mercy: https://scholarlyexchange.childrensmercy.org/papers/906 NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Echocardiography. -

Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 3054 Date: August 29, 2014 Change Request 8803

Department of Health & CMS Manual System Human Services (DHHS) Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 3054 Date: August 29, 2014 Change Request 8803 SUBJECT: Ventricular Assist Devices for Bridge-to-Transplant and Destination Therapy I. SUMMARY OF CHANGES: This Change Request (CR) is effective for claims with dates of service on and after October 30, 2013; contractors shall pay claims for Ventricular Assist Devices as destination therapy using the criteria in Pub. 100-03, part 1, section 20.9.1, and Pub. 100-04, Chapter 32, sec. 320. EFFECTIVE DATE: October 30, 2013 *Unless otherwise specified, the effective date is the date of service. IMPLEMENTATION DATE: September 30, 2014 Disclaimer for manual changes only: The revision date and transmittal number apply only to red italicized material. Any other material was previously published and remains unchanged. However, if this revision contains a table of contents, you will receive the new/revised information only, and not the entire table of contents. II. CHANGES IN MANUAL INSTRUCTIONS: (N/A if manual is not updated) R=REVISED, N=NEW, D=DELETED-Only One Per Row. R/N/D CHAPTER / SECTION / SUBSECTION / TITLE D 3/90.2.1/Artifiical Hearts and Related Devices R 32/Table of Contents N 32/320/Artificial Hearts and Related Devices N 32/320.1/Coding Requirements for Furnished Before May 1, 2008 N 32/320.2/Coding Requirements for Furnished After May 1, 2008 N 32/320.3/ Ventricular Assist Devices N 32/320.3.1/Postcardiotomy N 32/320.3.2/Bridge-To -Transplantation (BTT) N 32/320.3.3/Destination Therapy (DT) N 32/320.3.4/ Other N 32/320.4/ Replacement Accessories and Supplies for External Ventricular Assist Devices or Any Ventricular Assist Device (VAD) III. -

Heterotaxy and Complex Structural Heart Defects in a Mutant Mouse Model of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Heterotaxy and complex structural heart defects in a mutant mouse model of primary ciliary dyskinesia Serena Y. Tan, … , Linda Leatherbury, Cecilia W. Lo J Clin Invest. 2007;117(12):3742-3752. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI33284. Research Article Development Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a genetically heterogeneous disorder associated with ciliary defects and situs inversus totalis, the complete mirror image reversal of internal organ situs (positioning). A variable incidence of heterotaxy, or irregular organ situs, also has been reported in PCD patients, but it is not known whether this is elicited by the PCD- causing genetic lesion. We studied a mouse model of PCD with a recessive mutation in Dnahc5, a dynein gene commonly mutated in PCD. Analysis of homozygous mutant embryos from 18 litters yielded 25% with normal organ situs, 35% with situs inversus totalis, and 40% with heterotaxy. Embryos with heterotaxy had complex structural heart defects that included discordant atrioventricular and ventricular outflow situs and atrial/pulmonary isomerisms. Variable combinations of a distinct set of cardiovascular anomalies were observed, including superior-inferior ventricles, great artery alignment defects, and interrupted inferior vena cava with azygos continuation. The surprisingly high incidence of heterotaxy led us to evaluate the diagnosis of PCD. PCD was confirmed by EM, which revealed missing outer dynein arms in the respiratory cilia. Ciliary dyskinesia was observed by videomicroscopy. These findings show that Dnahc5 is required for the specification of left-right asymmetry and suggest that the PCD-causing Dnahc5 mutation may also be associated with heterotaxy. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/33284/pdf Research article Heterotaxy and complex structural heart defects in a mutant mouse model of primary ciliary dyskinesia Serena Y. -

Atrial Septal Stenting to Increase Interatrial Shunting in Cyanotic Congenital Heart Diseases: a Report of Two Cases

422 Türk Kardiyol Dern Arş - Arch Turk Soc Cardiol 2011;39(5):422-426 doi: 10.5543/tkda.2011.01368 Atrial septal stenting to increase interatrial shunting in cyanotic congenital heart diseases: a report of two cases Siyanotik doğuştan kalp hastalıklarında interatriyal şantı artırmak amacıyla atriyal septuma stent uygulaması: İki olgu sunumu Yalım Yalçın, M.D., Cenap Zeybek, M.D.,§ İbrahim Özgür Önsel, M.D.,# Mehmet Salih Bilal, M.D.† Departments of Pediatric Cardiology, #Anesthesiology and Reanimation, and †Cardiovascular Surgery, Medicana International Hospital; §Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Şişli Florence Nightingale Hospital, İstanbul Summary – Aiming to increase mixing at the atrial level, Özet – Siyanotik doğuştan kalp hastalığı tanısıyla izle- atrial septal stenting was performed in two pediatric nen iki bebekte, atriyal düzeyde karışımı artırmak ama- cases with cyanotic congenital cardiac diseases. The cıyla atriyal septuma stent yerleştirme işlemi uygulandı. first case was a 3-month-old male infant with transpo- Birinci olgu, büyük arterlerin transpozisyonu tanısıyla sition of the great arteries. The second case was an izlenen üç aylık bir erkek bebekti. Diğer olgu, ameliyat 18-month-old male infant with increased central venous sonrası dönemde sağ ventrikül çıkım yolu tıkanıklığına pressure due to postoperative right ventricular outflow bağlı olarak santral venöz basınç yüksekliği gelişen 18 tract obstruction. Premounted bare stents of 8 mm in aylık bir erkek bebekti. Her iki olguda da 8 mm çapında, diameter were used in both cases. The length of the balona monte edilmiş çıplak stent kullanıldı. Stent uzun- stent was 20 mm in the first case and 30 mm in the lat- luğu ilk olguda 20 mm, ikinci olguda 30 mm idi. -

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ achd.stanfordchildrens.org | achd.stanfordhealthcare.org About Congenital Heart Disease What is congenital heart disease? Congenital heart disease, also called congenital heart defect (CHD), is a heart problem that a baby is born with. When the heart forms in the womb, it develops incorrectly and does not work properly, which changes how the blood flows through the heart. What causes congenital heart defects? In most cases, there is no clear cause. It can be linked to something out of the ordinary happening during gestation, including a viral infection or exposure to environmental factors. Or, it may be linked to a single gene defect or chromosome abnormalities. How common is CHD in the United States among children? Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defects in children in the United States. Approximately 1 in 100 babies are born with a heart defect. What are the most common types of congenital heart defects in children? In general, CHDs disrupt the flow of blood in the heart as it passes to the lungs or to the body. The most common congenital heart defects are abnormalities in the heart valves or a hole between the chambers of the heart (ventricles). Examples include ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), and bicuspid aortic valve. At the Betty Irene Moore Children’s Heart Center at Stanford Children’s Health, we are known across the nation and world for treating some of the most complex congenital heart defects with outstanding outcomes. Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ | 2 Is CHD preventable? In some cases, it could be preventable. -

Pulmonary-Atresia-Mapcas-Pavsdmapcas.Pdf

Normal Heart © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic NOTES: Children’s Heart Clinic, P.A., 2530 Chicago Avenue S, Ste 500, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-8800 * East Metro: 651-220-8800 * Toll Free: 1-800-938-0301 * Fax: 612-813-8825 Children’s Minnesota, 2525 Chicago Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-6000 * East Metro: 651-220-6000 © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic Reviewed March 2019 Pulmonary Atresia, Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries (PA/VSD/MAPCAs) Pulmonary atresia (PA), ventricular septal defect (VSD) and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs) is a rare type of congenital heart defect, also referred to as Tetralogy of Fallot with PA/MAPCAs. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common cyanotic heart defect and occurs in 5-10% of all children with congenital heart disease. The classic description of TOF includes four cardiac abnormalities: overriding aorta, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), large perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD), and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO). About 20% of patients with TOF have PA at the infundibular or valvar level, which results in severe right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. PA means that the pulmonary valve is closed and not developed. When PA occurs, blood can not flow through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. Instead, the child is dependent on a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or multiple systemic collateral vessels (MAPCAs) to deliver blood to the lungs for oxygenation. These MAPCAs usually arise from the de- scending aorta and subclavian arteries. Commonly, the pulmonary arteries are abnormal, with hypoplastic (small and underdeveloped) central and branch pulmonary arteries and/ or non-confluent central pulmonary arteries. -

Situs Inversus Totalis - a Case Report

IOSR Journal of Applied Physics (IOSR-JAP) e-ISSN: 2278-4861. Volume 3, Issue 6 (May. - Jun. 2013), PP 12-16 www.iosrjournals.org Situs Inversus Totalis - A Case Report *Dr. G.Supriya,** Dr. S.Saritha, **Dr. Seema Madan *Assistant professor, ** Professor of Anatomy, GMC, Secunderabad Abstract: SITUS INVERSUS TOTALIS is a congenital positional anomaly characterized by transposition of abdominal viscera associated with a right sided heart (Dextrocardia) .It was Mathew Baillie who first described situs inversus totalis in early twentieth century. A transposed thoracic and abdominal organ is a mirror image of the normal anatomy when examined or visualized by tests such as x-ray filming. The term situs inversus is a short form of the Latin meaning inverted position of the internal organs. Generally individuals with situs inversus totalis are asymptomatic and have a normal life expectancy. Many people with situs inversus totalis are unaware of their unusual anatomy until they seek medical attention for an unrelated condition. The reversal of the organs may lead to some confusion as many signs and symptoms will be on the reverse side. A 27 years old male patient reported to the Department of Nephrology with the c/o left sided flank pain since 1 week. The Chest X-ray, Ultrasonography, CT scan and MRI were done and he was diagnosed as SITUS INVERSUS TOTALIS. The anatomic, pathologic, embryologic and etiology of complete Situs inversus and related abnormalities are presented in this case with special emphasis to genetic correlation. Key words: Situs inversus totalis, Dextrocardia, Congenital, Transposition, Thoracic and abdominal organs. I.