A Study of Einstürzende Neubauten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heiser, Jörg. “Do It Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005

Heiser, Jörg. “Do it Again,” Frieze, Issue 94, October 2005. In conversation with Marina Abramovic Marina Abramovic: Monica, I really like your piece Hausfrau Swinging [1997] – a video that combines sculpture and performance. Have you ever performed this piece yourself? Monica Bonvicini: No, although my mother said, ‘you have to do it, Monica – you have to stand there naked wearing this house’. I replied, ‘I don’t think so’. In the piece a woman has a model of a house on her head and bangs it against a dry-wall corner; it’s related to a Louise Bourgeois drawing from the ‘Femme Maison’ series [Woman House, 1946–7], which I had a copy of in my studio for a long time. I actually first shot a video of myself doing the banging, but I didn’t like the result at all: I was too afraid of getting hurt. So I thought of a friend of mine who is an actor: she has a great, strong body – a little like the woman in the Louise Bourgeois drawing that inspired it – and I knew she would be able to do it the right way. Jörg Heiser: Monica, after you first showed Wall Fuckin’ in 1995 – a video installation that includes a static shot of a naked woman embracing a wall, with her head outside the picture frame – you told me one critic didn’t talk to you for two years because he was upset it wasn’t you. It’s an odd assumption that female artists should only use their own bodies. -

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

Friktionen 44/2018

FRIKTIONEN Beiträge zu Politik und Gegenwartskultur Ausgabe 44/2018 Guerilla Gardening FRIKTIONEN 44/2018 Editorial S. 2 Chinese Lesson S. 3 Bilderwitze (Thomas Glatz) S. 6 Der Überlebende S. 6 Umgedrehte Readymades IV (Thomas Glatz) S. 8 Blöde Geschichte (Thomas Glatz) S. 13 Cpt. Kirk &, Teil 17 S. 14 Klavierkonzert zu vier Händen (Thomas Glatz) S. 15 Einstürzende Neubauten: ‚Man muss nicht alles glauben was man hört‘ (Miss Harmlos) S. 15 Aus dem Plattenarchiv S. 26 Editorial Mit veritabler Verspätung gibt es anbei die neue Ausgabe der Friktionen, quasi mit einem Abschieds- titelbild aus dem Westend, das nun nicht mehr Redaktionsmittelpunkt ist. Das vermeintliche Guerilla- gardening ziert den Gehsteig vor einem von zwei Leerstandsobjekten im Viertel, die direkt gegenüber voneinander an der oberen Schwanthalerstraße liegen. Eines hat sogar schon eine Phantomhausbe- setzung überlebt. Auch ohne diesen Lokalkolorit mag man den Titel als Sinnbild für die Verwilderung der politischen Sitten lesen. Man sieht halt immer mehr vor allem braunen Schmutz im politischen Alltag. Der war wahrscheinlich vorher schon da, nur unter der Oberfläche. Das kann natürlich in keiner Weise beruhigen. Schließlich bringt Sichtbarkeit eines Phänomens auch immer eine neue soziale Dimension und Eskalationsstufe mit sich. Schmutz spielt dabei in den meisten Beiträgen zur Ausgabe eine eher untergeordnete Rolle, am ehes- ten noch in den wunderbaren Einlassungen von Miss Harmlos zu den Einstürzenden Neubauten. Thomas Glatz bereichert die Ausgabe um wundervolle Kurztexte rund um die Eigenheiten von Stadt- parks und Aufführungen von klassischer Musik und setzt seine Serie der Bilderwitze fort. Viel Spaß beim Lesen! Nach wie vor gilt die Einladung für ‚Friktionen’ zu schreiben, zu zeichnen oder zu fotografieren. -

Die Deutsche Nationalhymne

Wartburgfest 1817 III. Die deutsche Nationalhymne 1. Nationen und ihre Hymnen Seit den frühesten Zeiten haben Stämme, Völker und Kampfeinheiten sich durch einen gemeinsamen Gesang Mut zugesungen und zugleich versucht, den Gegner zu schrecken. Der altgriechische Päan ist vielleicht das bekannteste Beispiel. Parallel zum Aufkommen des Nationalismus entwickelten die Staaten nationale, identitätsstiftende Lieder. Die nieder- ländische Hymne stammt aus dem 16 Jahrhundert und gilt als die älteste. Wilhelmus von Nassawe bin ich von teutschem blut, dem vaterland getrawe bleib ich bis in den todt; 30 ein printze von Uranien bin ich frey unverfehrt, den könig von Hispanien hab ich allzeit geehrt. Die aus dem Jahre 1740 stammen Rule Britannia ist etwas jünger, und schon erheblich nationalistischer. When Britain first, at Heaven‘s command Arose from out the azure main; This was the charter of the land, And guardian angels sang this strain: „Rule, Britannia! rule the waves: „Britons never will be slaves.“ usw. Verbreitet waren Preisgesänge auf den Herrscher: Gott erhalte Franz, den Kaiser sang man in Österreich, God save the king in England, Boshe chrani zarja, was dasselbe bedeutet, in Rußland. Hierher gehören die dänische Hymne Kong Christian stod ved højen mast i røg og damp u. a. Die französische Revolution entwickelte eine Reihe von Revolutionsge- sängen, die durchweg recht brutal daherkommen, wie zum Beispiel das damals berühmte Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira, Les aristocrates à la lanterne! Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira, Les aristocrates on les pendra! also frei übersetzt: Schaut mal her, kommt zuhauf, wir hängen alle Fürsten auf! Auch die blutrünstige französische Nationalhymne, die Mar- seillaise, stammt aus dieser Zeit: Allons enfants de la patrie. -

"My Songs Require You to Listen to and Understand Each Line"

1984 APR With both records, there's afeeling of something intangible, of aband an insect with an odd number of wings, she loves him not. Finally, "Box reachingwhere they ought not to go-they provoke imagination and For Black Paul" begins as aWho Killed Cock Robin-style elegy for the inspire hyperbole. Both are testaments of romantic daring and sick destruction of The Birthday Party, and develops into ahuge and bloated obsessiveness, full of feverish images of guilt, pictures of murder that are dirge that aches with ayearning beauty, the voice dredging the loss to simultaneously horrendous and secretly attractive. produce the loneliest sound you've ever heard. It was at that point that it first became clear that Nick's songwriting was Of course it's not constructed without acertain humour, but even by departing from every mode known to rock music and developing into the standards of The Birthday Party, it's adark variety indeed -there's some new, iridescent form, in turns trenchant and direct, epic and not alot to laugh about. It's awork more contemplative than Marc overblown. Meanwhile, the band's music was hurling itself into astate of Almond's Torment And Toreros, but one that shares its total ambition. wild, epileptic disorder that seemed to be driven by astate of frenzy, even From Her To Eternity is astatement of romantic irrationalism, stretching in its most dangerously restrained moments. to the very limits. With The Birthday Party literallyfalling apart-Rowland SHoward had already gone and Blixa Bargeld from Einstürzende Neubauten 1ALK TO NICK Cave and you're talking to avariety of characters. -

The Experimental Music of Einstürzende Neubauten and Youth Culture in 1980S West Berlin

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-10-03 The Experimental Music of Einstürzende Neubauten and Youth Culture in 1980s West Berlin Ryszka, Michael Andrzej Ryszka, M. A. (2012). The Experimental Music of Einstürzende Neubauten and Youth Culture in 1980s West Berlin (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28149 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/259 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Experimental Music of Einstürzende Neubauten and Youth Culture in 1980s West Berlin by Michael Andrzej Ryszka A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC, SLAVIC AND EAST ASIAN STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER 2012 © Michael Andrzej Ryszka 2012 Abstract In this thesis I examine the music of West Berlin experimental music group Einstürzende Neubauten. The unique social, political, and economic conditions of West Berlin during the 1980s created a distinct urban environment that is reflected in the band’s music. The city has been preserved by Einstürzende Neubauten in the form of sound recordings, and conserved in the unique instruments originally found by the band on the streets of West Berlin. -

Baustellen Der Zerstörung Literatur, Architektur Und Dekonstruktion

BAUSTELLEN DER ZERSTÖRUNG LITERATUR, ARCHITEKTUR UND DEKONSTRUKTION CONSTRUCTION SITES OF DESTRUCTION LITERATURE, ARCHITECTURE, AND DECONSTRUCTION by Johannes Birke A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October, 2014 © 2014 Johannes Birke All Rights Reserved Intented to be blank ii Abstract My dissertation Construction Sites of Destruction. Literature, Architecture, and Deconstruction analyzes representational and epistemological modes of architectural destruction in literature, theory, and film since the 1960s. I argue in my thesis that architectural destruction challenges the limits of writing, building, and memory, and that this is integral to the production and understanding of architecture and literature in the late twentieth century. I take a decidedly transmedial perspective toward the relationship between architecture and literature, and include examples of painting, photography, and film. As a program of dismantling the ‘architecture’ of Western philosophical thought, the rise of deconstruction in the late 1960s found immediate resonance among the architects of the period. Deconstruction pervades their theoretical work no less than their actual processes of designing and building. I argue that deconstruction is central to not only the displacement of the system of architectural metaphors (in philosophy), but also with the concrete materiality of architecture itself. My thesis links the metaphorical and material aspects of architectural destruction in order to establish a new theoretical framework for the construction, representation, and reception of architecture in literature and cinema. Close readings of Thomas Bernhard’s novels Das Kalkwerk and Korrektur set up a ‘poetology of construction sites of destruction.’ With Bernhard, I show how architecture becomes an agent in both the processes of writing and destroying (itself, among other things). -

Marketing Plan

ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP An Allied Artists Int'l Company MARKETING & PROMOTION MARKETING PLAN: ROCKY KRAMER "FIRESTORM" Global Release Germany & Rest of Europe Digital: 3/5/2019 / Street 3/5/2019 North America & Rest of World Digital: 3/19/2019 / Street 3/19/2019 MASTER PROJECT AND MARKETING STRATEGY 1. PROJECT GOAL(S): The main goal is to establish "Firestorm" as an international release and to likewise establish Rocky Kramer's reputation in the USA and throughout the World as a force to be reckoned with in multiple genres, e.g. Heavy Metal, Rock 'n' Roll, Progressive Rock & Neo-Classical Metal, in particular. Servicing and exposure to this product should be geared toward social media, all major radio stations, college radio, university campuses, American and International music cable networks, big box retailers, etc. A Germany based advance release strategy is being employed to establish the Rocky Kramer name and bona fides within the "metal" market, prior to full international release.1 2. OBJECTIVES: Allied Artists Music Group ("AAMG"), in association with Rocky Kramer, will collaborate in an innovative and versatile marketing campaign introducing Rocky and The Rocky Kramer Band (Rocky, Alejandro Mercado, Michael Dwyer & 1 Rocky will begin the European promotional campaign / tour on March 5, 2019 with public appearances, interviews & live performances in Germany, branching out to the rest of Europe, before returning to the U.S. to kick off the global release on March 19, 2019. ALLIED ARTISTS INTERNATIONAL, INC. ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP 655 N. Central Ave 17th Floor Glendale California 91203 455 Park Ave 9th Floor New York New York 10022 L.A. -

Einstürzende Neubauten (DE)

2007-10-31 11:02 CET Einstürzende Neubauten (DE) 26 april - Stockholm, Berns 27 april - Göteborg, Trädgår'n I närmare 30 år har avantgardisterna Einstürzende Neubauten överröst oss med industriella tongångar och med första skivan på eget bolag, "Alles Wieder Offen", har de gjort ett av sina allra bästa album. Skivan spelades in under 200 dagar i bandets egen studio och finansierades av fans som har prenumererat på exklusiva skivor, webcasts mm via bandets hemsida www.neubauten.org. 2000 års "Silence is Sexy" fick oss kanske att tro att bandet hade lugnat ner sig och kanske till och med blivit tystare, men allt det ställs nu på ända. Bandet tar sitt uttryck vidare, använder både en stråkkvartett och konventionella instrument, givetvis vid sidan av sina hembyggda instrumentkreationer. 1981 släppte bandet första albumet "Kollaps", som sägs ha spelats in i ett hålrum under en motorväg i Berlin, och raserade alla konventioner med oljud, metalliska rytmer och avgrundsvrål. Det är ett banbrytande och samtidigt svårlyssnat album, men redan här förklarade Neubauten krig mot alla konventionella sätt att lyssna på musik och blev förgrundsfigurer i en ny våg av industriella band. Instrumenten stals från byggarbetsplatser, skrotupplag och järnaffärer. De spelade på stålfjädrar, metallrör, tryckluftsborrar, hammare, sågar och ostämda gitarrer, allt toppat med Blixa Bargelds hårresande skrik och feberaktigt apokalyptiska texter. Publiken blev lika delar chockerad, förbryllad och fascinerad. "Halber Mensch" (1985) och "Haus der Lüge" (1989) blev två milstolpar som än idag rankas som verkliga klassiker. På industripionjärernas senare skivor har de lugnat ner sig betydligt och har en mer konstnärlig och intellektuell framtoning, men det extrema och experimentella står ännu i centrum och de hittar ständigt nya sätt att förnya sig. -

Man Muß Die Neubauten Schon Sehr Und Bedingungslos Lieben, Wenn

von links nach rechts: Jochen Arbeit, Blixa Bargeld, Rudolf Moser, N.U. Unruh, Alexander Hacke © »Foto: Einstürzende Neubauten electronic press kit« »ALLES WIEDER OFFEN« Die neue CD und DVD der »EINSTÜRZENDEN NEUBAUTEN« Man muss die »NEUBAUTEN« schon sehr, arg sehr und sehr bedingungslos lieben, wenn man sagte, dass ihr neues Album »ALLES WIEDER OFFEN« „rundum“ gelungen sei. Sie haben es mir nie leicht gemacht und ich habe mich immer schwer mit ihnen getan. Seit dem Abgang von F.M. Einheit und »ENDE NEU«. Abgesehen von der »Initialzündung«, damals, einstens, irgendwann, mit »HAUS DER LÜGE«. Aber das ist so, immer, bei der Rezeption von Kunst. Bei großer KlangKunst gar, bei den »NEUBAUTEN« eben, die Ihresgleichen weder suchen noch finden würden. Wenn man ein gewisses Alter erreicht hat und dem FAN-Alter mit der dazugehörigen, bedingungslosen Hörigkeit zum Künstler entwachsen ist, also nicht à priori alles schätzt, was der macht und darüber hinaus über ein gehöriges Maß an künstlerischem Sachverstand verfügt, dann, dann wird es schwierig. Dann trennt man sich, oder rauft sich zusammen. Ich habe mich bislang immer wieder mit den NEUBAUTEN zusammengerauft. SUPPORTER aller drei Phasen. Der ich war und bin. Und, entgegen meinen ersten Unmutsäußerungen über das neue Album, auch in Phase IV sein werde. Wenn es denn ein solche geben wird. Gerüchte über eine Trennung werden derzeit nicht mehr nur hinter vorgehaltener Hand und nicht mehr nur von Außenstehenden geäußert. Aber Gerüchte halt. Zum Album. Den Musikern. N.U. Unruh ist der zuverlässige, jeden Punkt präzise rhythmisierende Pol der Band geblieben. Seine Arbeit überzeugt immer. Ein stiller Held. -

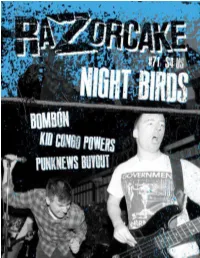

Razorcake Issue

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Curious about how to realistically help Razorcake? If you wish to donate through the mail, please rip this page out and send it to: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. PO Box 42129 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Just NAME: turn ADDRESS: the EMAIL: page. DONATION AMOUNT: 5D]RUFDNH*RUVN\3UHVV,QFD&DOLIRUQLDQRWIRUSUR¿WFRUSRUDWLRQLVUHJLVWHUHG DVDFKDULWDEOHRUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKWKH6WDWHRI&DOLIRUQLD¶V6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWHDQGKDV EHHQJUDQWHGRI¿FLDOWD[H[HPSWVWDWXV VHFWLRQ F RIWKH,QWHUQDO5HYHQXH &RGH IURPWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV,562XUWD[,'QXPEHULV <RXUJLIWLVWD[GHGXFWLEOHWRWKHIXOOH[WHQWSURYLGHGE\ODZ SUBSCRIBE AND HELP KEEP RAZORCAKE IN BUSINESS Subscription rates for a one year, six-issue subscription: U.S. – bulk: $16.50 • U.S. – 1st class, in envelope: $22.50 Prisoners: $22.50 • Canada: $25.00 • Mexico: $33.00 Anywhere else: $50.00 (U.S. funds: checks, cash, or money order) We Do Our Part www.razorcake.org Name Email Address City State Zip U.S. subscribers (sorry world, int’l postage sucks) will receive either Grabass Charlestons, Dale and the Careeners CD (No Idea) or the Awesome Fest 666 Compilation (courtesy of Awesome Fest). Although it never hurts to circle one, we can’t promise what you’ll get. Return this with your payment to: Razorcake, PO Box 42129, LA, CA 90042 If you want your subscription to start with an issue other than #72, please indicate what number. TEN NEW REASONS TO DONATE TO RAZORCAKE VPDQ\RI\RXSUREDEO\DOUHDG\NQRZRazorcake ALVDERQDILGHQRQSURILWPXVLFPDJD]LQHGHGLFDWHG WRVXSSRUWLQJLQGHSHQGHQWPXVLFFXOWXUH$OOGRQDWLRQV The Donation Incentives are… -

Titel, Text Nr

Land Titel, Text Nr. Kategorie Aba heidschi bumbeidschi 165 WEIHNACHTEN Abend wird es wieder über Wald und Feld 388 ZEIT Abendlied 323 ZEIT Ach bittrer Winter, wie bist du kalt 17 ZEIT Ach, wie ist's möglich dann 249 LIEBE Ade zur guten Nacht 322 ZEIT Ännchen von Tharau 310 LIEBE All mein Gedanken 31 LIEBE Alle Jahre wieder 347 WEIHNACHTEN Alle Vögel sind schon da 257 ZEIT Alle, die mit uns auf Kaperfahrt fahren 262 SCHIFF Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr 339 CHORAL Alleweil ein wenig lustig 306 LUSTIG Als ich bei meinen Schafen wacht 187 WEIHNACHTEN Als ich ein jung Geselle war 56 LEBEN Als ich einmal reiste 127 WANDERN Als unser Mops ein Möpschen war 377 LUSTIG Als wir jüngst in Regensburg waren 53 SCHIFF Am Brunnen vor dem Tore 295 WANDERN Am Weihnachtsbaum die Lichter brennen 11 WEIHNACHTEN An der Saale hellem Strande 212 LAND As Burlala geboren war 98 JUX Auf der Lüneburger Heide 101 LAND Auf der Rudelsburg 213 STUDENT Auf der schwäb'sche Eisebahne 385 LUSTIG Auf, auf zum fröhlichen Jagen 287 JAGD Auf, auf, ihr Wandersleut 18 WANDERN Auf, du junger Wandersmann 368 WANDERN Auf, Glückauf! Auf, Glückauf! 153 BERGBAU, HARZ Auferstanden aus Ruinen und der Zukunft 393 HYMNE zugewandt Bald gras ich am Neckar 29 LIEBE Bayernhymne 97 HYMNE Beim Kronenwirt, da ist heut' Jubel und Tanz 129 TANZ Beim Rosenwirt am Grabentor 45 STUDENT Bierlein, rinn! 45 STUDENT Bigben 4 Uhr 281 JUX Bolle reiste jüngst zu Pfingsten 148 JUX Bruder Jakob 238 ZEIT Brüder, reicht die Hand zum Bunde 104 HYMNE Bundeslied 223 STUDENT Bunt sind schon die Wälder 318 ZEIT