Maya Achi Marimba Music in Guatemala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Meanings of Marimba Music in Rural Guatemala

The Meanings of Marimba Music in Rural Guatemala Sergio J. Navarrete Pellicer Ph D Thesis in Social Anthropology University College London University of London October 1999 ProQuest Number: U643819 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643819 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis investigates the social and ideological process of the marimba musical tradition in rural Guatemalan society. A basic assumption of the thesis is that “making music” and “talking about music” are forms of communication whose meanings arise from the social and cultural context in which they occur. From this point of view the main aim of this investigation is the analysis of the roles played by music within society and the construction of its significance as part of the social and cultural process of adaptation, continuity and change of Achi society. For instance the thesis elucidates how the dynamic of continuity and change affects the transmission of a musical tradition. The influence of the radio and its popular music on the teaching methods, music genres and styles of marimba music is part of a changing Indian society nevertheless it remains an important symbols of locality and ethnic identity. -

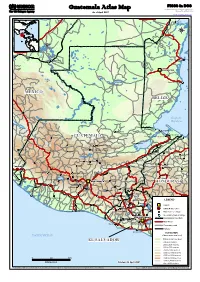

Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected] ((( Corozal Guatemala_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Balancan !! !! !! !! Tenosique Belize City !! BELMOPANBELMOPAN Stann Creek Town !! MEXICOMEXICO BELIZEBELIZE !! Golfo de Honduras San Juan ((( !! Lívingston !! El Achiotal !! Puerto Barrios GUATEMALAGUATEMALA Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ((( ((( ((( Soloma ((( Cuyamel Cobán ((( El Estor ((( ((( Chajul ((( !! ((( San Pedro Carchá ((( Morales !! Motozintla Huehuetenango !! San Cristóbal Verapaz ((( Cunen ((( ((( !! Macuelizo ((( ((( Los Amates((( Petoa ((( Cubulco Salamá Trinidad ((( ((( !! Gualán ((( !! !! ((( !! ((( San Sebastián ((( San Jerónimo ((( Jesus Maria La Agua ((( !! Rabinal ((( Protección ((( Joyabaj TapachulaTapachula Totonicapán ((( Zacapa !! Naranjito ((( ((( !! Tapachula ((( ((( Santa Bárbara ((( Quezaltenango !! Dulce Nombre ((( !! San José Poaquil !! Chiquimula !! !! Sololá !! Santa Rosa !! Comalapa ((( Patzún !! Santiago Atitlán !! Tecun Uman !! Chimaltenango GUATEMALAGUATEMALA !! Jalapa HONDURASHONDURAS Mazatenango HONDURASHONDURAS Antigua ((( !! Esquipulas !! !! Retalhuleu ((( !! ((( Ciudad Vieja ((( Monjas Alotenango ((( Nueva Ocotepeque !! ((( Santa Catarina Mita Amatitlán ((( ((( Patulul ((( Ayarza Río Bravo ((( ((( Metapán !! !! Escuintla ((( !! ((( !! Jutiapa((( ((( !! Champerico ((( !! Cuilapa !! Asunción Mita ((( Yamarang Pueblo Nuevo Tiquisate ((( Erandique Yupiltepeque ((( ((( Atescatempa Nueva Concepción LEGEND -

HISPANIC MUSIC for BEGINNERS Terminology Hispanic Culture

HISPANIC MUSIC FOR BEGINNERS PETER KOLAR, World Library Publications Terminology Spanish vs. Hispanic; Latino, Latin-American, Spanish-speaking (El) español, (los) españoles, hispanos, latinos, latinoamericanos, habla-español, habla-hispana Hispanic culture • A melding of Spanish culture (from Spain) with that of the native Indian (maya, inca, aztec) Religion and faith • popular religiosity: día de los muertos (day of the dead), santería, being a guadalupano/a • “faith” as expession of nationalistic and cultural pride in addition to spirituality Diversity within Hispanic cultures Many regional, national, and cultural differences • Mexican (Southern, central, Northern, Eastern coastal) • Central America and South America — influence of Spanish, Portuguese • Caribbean — influence of African, Spanish, and indigenous cultures • Foods — as varied as the cultures and regions Spanish Language Basics • a, e, i, o, u — all pure vowels (pronounced ah, aey, ee, oh, oo) • single “r” vs. rolled “rr” (single r is pronouced like a d; double r = rolled) • “g” as “h” except before “u” • “v” pronounced as “b” (b like “burro” and v like “victor”) • “ll” and “y” as “j” (e.g. “yo” = “jo”) • the silent “h” • Elisions (spoken and sung) of vowels (e.g. Gloria a Dios, Padre Nuestro que estás, mi hijo) • Dipthongs pronounced as single syllables (e.g. Dios, Diego, comunión, eucaristía, tienda) • ch, ll, and rr considered one letter • Assigned gender to each noun • Stress: on first syllable in 2-syllable words (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) • Stress: on penultimate syllable in 3 or more syllables (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) Any word which doesn’t follow these stress rules carries an accent mark — é, á, í, ó, étc. -

La Marimba Tradicional Afroesmeraldeña, Ecuador

CUADERNOS DE MÚSICA IBEROAMERICANA. Vol. 30 enero-diciembre 2017, 179-205 ISSN-e 2530-9900 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/CMIB.58569 FERNANDO PALACIOS MATEOS Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sonoridades africanas en Iberoamérica: La marimba tradicional afroesmeraldeña, Ecuador African Sonorities in Iberian America: The Traditional Afro-Esmeraldan Marimba from Ecuador Los instrumentos musicales reflejan, tanto en sus sonoridades como en sus materiales de construcción y disposición física, un proceso histórico social y una realidad cultural de- terminados; constituyen ámbitos de lectura de las distintas culturas en las que se insertan. El presente artículo aborda desde el contexto sociocultural, histórico y organológico el ins- trumento musical representativo de la cultura afrodescendiente del litoral pacífico del norte de Ecuador, la marimba. Transita por sus orígenes, materiales y técnicas de cons- trucción, así como por sus características musicales representativas. La población afrodes- cendiente de la provincia de Esmeraldas, conformada progresivamente desde la diáspora afroamericana hasta nuestros días, constituye a la marimba como un ícono de su cultura, un cálido timbre que la representa. Palabras clave: marimba, sonoridad, afrodescendiente, diáspora, Esmeraldas, Ecuador, África, Iberoamérica. Musical instruments reflect a social-historical process and a specific cultural reality in their sonorities, the materials from which they were built and their physical layout. They serve as vehicles for interpreting the different cultures of which they form part. This article examines the socio-cultural, historical and organological context of the musical instrument representative of Afro-descendant culture from the Pacific coast of the north of Ecuador: the marimba. It looks at its origins, materials and construction techniques, as well as its representative musical characteristics. -

Cooperative Agreement on Human Settlements and Natural Resource Systems Analysis

COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT ON HUMAN SETTLEMENTS AND NATURAL RESOURCE SYSTEMS ANALYSIS CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG University of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Gro'p Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreemeat (USAID) Clark University Institute for Development Anthropology International Development Program Suite 302, P.O. Box 818 950 Main Street 99 Collier Street Worcester, MA 01610 Binghamton, NY 13902 CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG Univer ity of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Group Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreement (USAID) August 1983 THE ORGANIZATION OF SPACE IN THE CENTRAL BELT OF GUATEMALA (ORGANIZACION DEL ESPACIO EN LA FRANJA CENTRAL DE LA REPUBLICA DE GUATEMALA) Juan Francisco Leal R., Coordinator of the Study Secretaria General del Consejo Nacional de Planificacion Economica (SGCNPE) and Agencia Para el Desarrollo Internacional (AID) Instituto de Fomento Municipal (INFOM) Programa: Estudios Integrados de las Areas Rurales (EIAR) Guatemala, Octubre 1981 Introduction In 1981 the Guatemalan Institute for Municipal Development (Instituto de Fomento Municipal-INFOM) under its program of Integrated Studies of Rural Areas (Est6dios Integrados de las Areas Rurales-EIAR) completed the work entitled Organizacion del Espcio en la Franja Centrol de la Republica de Guatemala (The Organization of Space in the Central Belt of Guatemala). This work had its origins in an agreement between the government of Guatemala, represented by the General Secretariat of the National Council for Economic Planning, and the government of the United States through its Agency for International Development. -

Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Linguistics Faculty Publications Linguistics 3-2016 Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala Rusty Barrett University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub Part of the Communication Commons, Language Interpretation and Translation Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Repository Citation Barrett, Rusty, "Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala" (2016). Linguistics Faculty Publications. 72. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub/72 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala Notes/Citation Information Published in Language & Communication, v. 47, p. 144-153. Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The document available for download is the authors' post-peer-review final draft of the ra ticle. Digital Object Identifier (DOI) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2015.08.005 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub/72 Mayan language revitalization, hip hop, and ethnic identity in Guatemala Rusty Barrett, University of Kentucky to appear, Language & Communiction (46) Abstract: This paper analyzes the language ideologies and linguistic practices of Mayan-language hip hop in Guatemala, focusing on the work of the group B’alam Ajpu. -

Relationship with Percussion Instruments

Multimedia Figure X. Building a Relationship with Percussion Instruments Bill Matney, Kalani Das, & Michael Marcionetti Materials used with permission by Sarsen Publishing and Kalani Das, 2017 Building a relationship with percussion instruments Going somewhere new can be exciting; it might also be a little intimidating or cause some anxiety. If I go to a party where I don’t know anybody except the person who invited me, how do I get to know anyone else? My host will probably be gracious enough to introduce me to others at the party. I will get to know their name, where they are from, and what they commonly do for work and play. In turn, they will get to know the same about me. We may decide to continue our relationship by learning more about each other and doing things together. As music therapy students, we develop relationships with music instruments. We begin by learning instrument names, and by getting to know a little about the instrument. We continue our relationship by learning technique and by playing music with them! Through our experiences and growth, we will be able to help clients develop their own relationships with instruments and music, and therefore be able to 1 strengthen the therapeutic process. Building a relationship with percussion instruments Recognize the Know what the instrument is Know where the Learn about what the instrument by made out of (materials), and instrument instrument is or was common name. its shape. originated traditionally used for. We begin by learning instrument names, and by getting to know a little about the instrument. -

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques JULY 2018 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard) *TC 1-19.30 (TC 12-43) Training Circular Headquarters No. 1-19.30 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 July 2018 Percussion Techniques Contents Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PERCUSSION PLAYING ................................................. 1-1 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Definitions .................................................................................................................. 1-1 Total Percussionist .................................................................................................... 1-1 General Rules for Percussion Performance .............................................................. 1-2 Chapter 2 SNARE DRUM .......................................................................................................... 2-1 Snare Drum: Physical Composition and Construction ............................................. -

Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion

Requirements for Audition 1 Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion March 2019 The NZSO tunes at A440. Auditions must be unaccompanied. Solo 01 | BACH | LUTE SUITE IN E MINOR MVT. 6 – COMPLETE (NO REPEATS) 02 | DELÉCLUSE | ETUDE NO. 9 FROM DOUZE ETUDES - COMPLETE Excerpts BASS DRUM 7 03 | BRITTEN | YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO THE ORCHESTRA .................................. 7 04 | MAHLER | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 1 ......................................................................... 8 05 | PROKOFIEV | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 4 .................................................................... 9 06 | SHOSTAKOVICH | SYMPHONY NO. 11 MVT. 1 .........................................................10 07 | STRAVINSKY | RITE OF SPRING ...............................................................................10 08 | TCHAIKOVSKY | SYMPHONY NO. 4 MVT. 4 ..............................................................12 BASS DRUM WITH CYMBAL ATTACHMENT 13 09 | STRAVINSKY | PETRUSHKA (1947) ...........................................................................13 New Zealand Symphony Orchestra | Sub-Principal Percussion | March 2019 2 Requirements for Audition CYMBALS 14 10 | DVOŘÁK | SCHERZO CAPRICCIOSO ........................................................................14 11 | MUSSORGSKY | NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN .........................................................14 12 | RACHMANINOV | PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 MVT. 3 ................................................15 13 | SIBELIUS | FINLANDIA ................................................................................................15 -

Análisis Del Léxico De La Música De Los Reguetoneros Puertorriqueños De

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University World Languages and Cultures Theses Department of World Languages and Cultures 4-21-2009 El Reguetón: Análisis Del Léxico De La Música De Los Reguetoneros Puertorriqueños Ashley Elizabeth Wood Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mcl_theses Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Wood, Ashley Elizabeth, "El Reguetón: Análisis Del Léxico De La Música De Los Reguetoneros Puertorriqueños." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mcl_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of World Languages and Cultures at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EL REGUETÓN: ANÁLISIS DEL LÉXICO DE LA MÚSICA DE LOS REGUETONEROS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS by ASHLEY ELIZABETH WOOD Under the Direction of Carmen Schlig ABSTRACT This paper examines some of the linguistic qualities of reggaeton in order to determine to which extent the music represents the speech of the urban residents of Puerto Rico. The lyrics are analyzed in order to see if they are used only within the context of reggaeton or if they are part of the Puerto Rican lexicon in general. The political context of Puerto Rico with respect to the United States is taken in to consideration with the formation of Anglicisms and the use of English. The paper summarizes the current knowledge of the Puerto Rican lexicon and highlights two linguistic studies that focus on reggaeton in addition to providing general background information about the genre. -

BAJA VERAPAZ CHIMALTENANGO CHIQUIMULA Direcciones De Las

Direcciones de las Oficinas del Registro Nacional de las Personas Abril 15́ No. DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO REGISTRO AUXILIAR DIRECCION SEDE ALTA VERAPAZ 1 ALTA VERAPAZ COBAN 4a. avenida 4-50, Barrio Santo Domingo, zona 3 2 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA CRUZ VERAPAZ Calle 3 de Mayo, Zona 4 3 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN CRISTOBAL VERAPAZ 3a. Avenida 1-38 Zona 1, Barrio Santa Ana 4 ALTA VERAPAZ TACTIC 8 Avenida 4-72 Zona 1, Barrio La Asunción 5 ALTA VERAPAZ TAMAHU Barrio San Pablo, Tamahu 6 ALTA VERAPAZ TUCURU Barrio El Centro, Calle Principal, Avenida Tucurú 7 ALTA VERAPAZ PANZOS Barrio el Centro, Calle del Estadio a 150 Mts. De la Municipalidad 8 ALTA VERAPAZ SENAHU Calle Principal del Municipio de Senahú 9 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN PEDRO CARCHA 2a. Calle 12-58 zona 5, Barrio Chibujbu 10 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN JUAN CHAMELCO 2a. Ave. Barrio san Juan 11 ALTA VERAPAZ LANQUIN Cruce el Pajal Sebol Lanquin 12 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA MARIA CAHABON Barrio Santiago 89-97 zona 0, camino a Escuela Saquija 13 ALTA VERAPAZ CHISEC Barrio el Centro, Lote 241-1 14 ALTA VERAPAZ CHAHAL Barrio el Centro, a un costado del TSE 15 ALTA VERAPAZ FRAY BARTOLOME DE LAS CASAS F.T.N. 0-70 zona 1 16 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA CATALINA LA TINTA Barrio Centro Zona 4 17 ALTA VERAPAZ RAXRUHA barrio concepcion lote 47, centro urbano poligono 1, camino a la Aldea la Isla BAJA VERAPAZ 1 BAJA VERAPAZ SALAMA 6a Avenida 5-71 Zona 1, salama 2 BAJA VERAPAZ SAN MIGUEL CHICAJ Cantón La Cruz 3 BAJA VERAPAZ RABINAL 3a. -

Una Aproximación Urbana a La Música De Marimba

Una aproximación urbana a la Música de Marimba ADRIAN SABOGAL PALOMINO ASESOR: RICHARD NARVÁEZ PROYECTO DE GRADO PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA FACULTAD DE ARTES Carrera de Estudios Musicales con Énfasis en Jazz (Guitarra) Bogotá D.C. 2010 5 Agradecimientos Quiero agradecer a Dios, a mis padres y a toda mi familia, por ser toda fuente de alivio y fortaleza en mi vida. Agradezco a Richard Narváez y a todos los maestros que me brindaron de una u otra forma sus conocimientos. Agradezco a todos los músicos que fueron entrevistados por su disposición y gran aporte al presente trabajo. Finalmente quiero hacer un agradecimiento especial al Taita Oscar Mojomboy y a Gaviota Acevedo quien ha sido un apoyo constante y esencial en todo momento. 6 Tabla de contenidos. Pág. I Abstract 8 II Introducción 9 1. Antecedentes 10 2. Objetivos 2.1. General 11 2.2. Específicos 12 2.3 Justificación 12 3. Metodología 3.1 Recopilación de material bibliográfico y transcripciones. 13 3.2 Relatos de la Música urbana inspirada en la tradición de la Marimba. 14 3.3 Trabajo de campo. 15 3.4 Análisis 18 Una aproximación urbana a la Música de Marimba. Capítulo 1 Música de Marimba a) Roles de cada instrumento 19 b) Forma del currulao 22 Capítulo 2 Algunos antecedentes de la síntesis de géneros musicales. a) Primitivismo: Música del siglo XX 24 b) Jazz Fusión 25 Capítulo 3 Análisis y Síntesis de componentes musicales. a) Currulao Acurrucao- J.S Monsalve 27 b) La Rana- Adrian Sabogal 31 Capítulo 4 Conclusión 33 Bibliografía 35 Discografía 36 Videografía 36 Entrevistas 37 Anexos A.