Zona Paz Economic Corridor Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

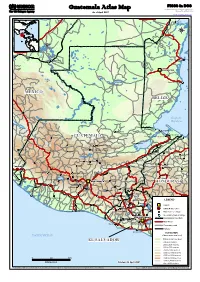

Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected] ((( Corozal Guatemala_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Balancan !! !! !! !! Tenosique Belize City !! BELMOPANBELMOPAN Stann Creek Town !! MEXICOMEXICO BELIZEBELIZE !! Golfo de Honduras San Juan ((( !! Lívingston !! El Achiotal !! Puerto Barrios GUATEMALAGUATEMALA Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ((( ((( ((( Soloma ((( Cuyamel Cobán ((( El Estor ((( ((( Chajul ((( !! ((( San Pedro Carchá ((( Morales !! Motozintla Huehuetenango !! San Cristóbal Verapaz ((( Cunen ((( ((( !! Macuelizo ((( ((( Los Amates((( Petoa ((( Cubulco Salamá Trinidad ((( ((( !! Gualán ((( !! !! ((( !! ((( San Sebastián ((( San Jerónimo ((( Jesus Maria La Agua ((( !! Rabinal ((( Protección ((( Joyabaj TapachulaTapachula Totonicapán ((( Zacapa !! Naranjito ((( ((( !! Tapachula ((( ((( Santa Bárbara ((( Quezaltenango !! Dulce Nombre ((( !! San José Poaquil !! Chiquimula !! !! Sololá !! Santa Rosa !! Comalapa ((( Patzún !! Santiago Atitlán !! Tecun Uman !! Chimaltenango GUATEMALAGUATEMALA !! Jalapa HONDURASHONDURAS Mazatenango HONDURASHONDURAS Antigua ((( !! Esquipulas !! !! Retalhuleu ((( !! ((( Ciudad Vieja ((( Monjas Alotenango ((( Nueva Ocotepeque !! ((( Santa Catarina Mita Amatitlán ((( ((( Patulul ((( Ayarza Río Bravo ((( ((( Metapán !! !! Escuintla ((( !! ((( !! Jutiapa((( ((( !! Champerico ((( !! Cuilapa !! Asunción Mita ((( Yamarang Pueblo Nuevo Tiquisate ((( Erandique Yupiltepeque ((( ((( Atescatempa Nueva Concepción LEGEND -

Cooperative Agreement on Human Settlements and Natural Resource Systems Analysis

COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT ON HUMAN SETTLEMENTS AND NATURAL RESOURCE SYSTEMS ANALYSIS CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG University of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Gro'p Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreemeat (USAID) Clark University Institute for Development Anthropology International Development Program Suite 302, P.O. Box 818 950 Main Street 99 Collier Street Worcester, MA 01610 Binghamton, NY 13902 CENTRAL PLACE SYSTEMS IN GUATEMALA: THE FINDINGS OF THE INSTITUTO DE FOMENTO MUNICIPAL (A PRECIS AND TRANSLATION) RICHARD W. WILKIE ARMIN K. LUDWIG Univer ity of Massachusetts-Amherst Rural Marketing Centers Working Group Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreement (USAID) August 1983 THE ORGANIZATION OF SPACE IN THE CENTRAL BELT OF GUATEMALA (ORGANIZACION DEL ESPACIO EN LA FRANJA CENTRAL DE LA REPUBLICA DE GUATEMALA) Juan Francisco Leal R., Coordinator of the Study Secretaria General del Consejo Nacional de Planificacion Economica (SGCNPE) and Agencia Para el Desarrollo Internacional (AID) Instituto de Fomento Municipal (INFOM) Programa: Estudios Integrados de las Areas Rurales (EIAR) Guatemala, Octubre 1981 Introduction In 1981 the Guatemalan Institute for Municipal Development (Instituto de Fomento Municipal-INFOM) under its program of Integrated Studies of Rural Areas (Est6dios Integrados de las Areas Rurales-EIAR) completed the work entitled Organizacion del Espcio en la Franja Centrol de la Republica de Guatemala (The Organization of Space in the Central Belt of Guatemala). This work had its origins in an agreement between the government of Guatemala, represented by the General Secretariat of the National Council for Economic Planning, and the government of the United States through its Agency for International Development. -

DIRECCION SUPERIOR SUBDIRECCIÓN ADMINISTRATIVA Subdirectoa: Licda

DIRECCION SUPERIOR SUBDIRECCIÓN ADMINISTRATIVA Subdirectoa: Licda. Mary Carmen de León Monterroso Responsable de actualización de información: Ronaldo Castro Herrera Fecha de emisión: 30/06/2019 (Artículo 10, numeral 29, Ley de Acceso a la Información Pública) MEDIDAS Y REMEDIDAS DE TERRENOS BALDIOS APROBADAS Municipio, No. Nombre Aprobación Fecha Modificación Fecha Departamento FINCA URBANA AV 1 SUR #22 ANTIGUA SACATEPEQUEZ ACDO. GUB. S/N 18/06/1971 GUATEMALA 2 FINCA OJO DE AGUA MOYUTA, JUTIAPA ACDO. GUB. S/N 30/05/1972 FINCA (NO INDICA 3 SACATEPEQUEZ ACDO. GUB. S/N 30/03/1981 GENERALES) FINCA RUSTICA 48060 4 GUATEMALA ACDO. GUB. S/N 08/09/1981 F183 L957 FINCA RUSTICA 7,172 5 SAN MARCOS ACDO. GUB. 103-83 15/02/1983 FOLIO 6, LIBRO 42 FRAY BARTOLOME 6 COMUNIDAD RAXAJA DE LAS CASAS, ALTA ACDO. GUB. 119-84 2/28/1984 VERAPAZ. FINCAS 478, 112 Y 49 7 F128, 436 Y 100 L28 Y SACATEPEQUEZ ACDO. GUB. 264-85 04/10/1984 7 FINCA NO. 1079, 8 ALTA VERAPAZ ACDO. GUB. 291-85 15/04/1985 FOLIO 209, LIBRO 50 FINCA RUSTICA NO. 9 8846, FOLIO 168, BAJA VERAPAZ ACDO. GUB. 311-85 17/04/1985 LIBRO 29 10 FINCA 667 F140 L12 TOTONICAPAN ACDO. GUB. 705-85 16/08/1985 FINCA URBANA 10,252, FOLIO 35, 11 SAN MARCOS ACDO. GUB. 756-85 29/10/1985 LIBRO 58 DE SAN MARCOS FINCA RUSTICA 12 SUCHITEPEQUEZ ACDO. GUB. 1079-85 11/11/1985 12736, F214 L66 LA LIBERTAD, 13 BALDÍO PEÑA ROJA ACDO. GUB. 863-86 27/11/1986 HUEHUETENANGO BALDÍO COMUNIDAD CHISEC, ALTA 14 ACDO. -

Departamento De Quiché Municipio De Chajul

CODIGO: AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS E INUNDACIONES 1405 DEPARTAMENTO DE QUICHÉ 8 AMEN AZA H MUNICIPIO DE CHAJUL u POR DESLIZAMIEN TOS 435000.000000 440000.000000 445000.000000 450000.000000 455000.000000 460000.000000 e Río Piedras Blancas 91°6'W 91°3'W 91°0'W 90°57'W 90°54'W 90°51'W h R La pred ic c ión d e esta a m ena za utiliza la m eto d o lo gía rec o no c id a Piedras í o P u Blancas ie d e Mo ra -V a hrso n, pa ra estim a r la s a m ena za s d e d esliza m iento s a dr Yulnacap a Buenos Todos " s un nivel d e d eta lle d e 1 kilóm etro . Esta c o m pleja m o d ela c ión utiliza e H B "Aires "Santos u la una c o m b ina c ión d e d a to s so b re la lito lo gía , la hum ed a d d el suelo , t n e c Buen Santa as Camino pend iente y pro nóstic o s d e tiem po en este c a so prec ipita c ión e h Barillas " Maria El Mirador Dolores " u " a c um ula d a que CATHALAC genera d ia ria m ente a tra vés d el n e Cerro y m o d elo m eso sc a le PSU /N CAR, el MM5. su t a "Conanimox a ul Q e ío Y n Comunidad n R u Santa Se estim a esta a m ena za en térm ino s d e ‘Ba ja ’, ‘Med ia ’ y ‘Alta ‘. -

Guatemala Memory of Silence: Report of the Commission For

_. .... _-_ ... _-------_.. ------ .f) GUATEMALA MEMORIA DEL 51LENCIO GUATEMALA MEMORIA DE: "<" 'AL TZ'INIL NA'TAB'AL TZ'INIL NA'TAB'AL TZ'INIL NA'TAB'AL TZ" , C NAJSA'N TUJ QLOLJ B'I QLOLJ B'INCHB': 'ATAB'AL 51LAN NATAB'A ~N NATAB'AL SIL ~NT'IL YU'AM K'UULANTl , U'AM K'UULANl . Nt B'ANITAJIK TZ'ILANEE .. ' B'ANITAJIK T: . 'CHIL NACHB'AL TE JUTZE'CHIL N , r 'EB'ANIL TZET MAC MACH XJALAN '~l QAB'IIM TAJ RI QA I QAB'IIM TAJ R! ~ ~AB'llAl TZ'INANK'ULA LAL SNAB'ILAL 1 I GUATEMALA MEMORIA LA MEMORIA DE · E Ai.. TZ'ENil NA'TAB'AL TZ'IN L NA'TAB'Al TZ' : i,& (~A~SA'N TUJ QLOLJ B'INC QLOLJ B'INCHB' i ~A'!"4B'Al SllAN NATAB'AL SI NATAB'Al Sil , NT'H.. YU'AM K'UULANT'IL YU 'AM K'UUlAN1 .. i B'Ar~rrAJiK T M B'ANITAJIK T. I~ HH. Nt~,.CHB' Z JU 'CHH_ ~ gi! EB'fU\BL T'Z ALAN fJ ,H QAS'nM . J R ~Sr"AB';lAL LAl i ,tlG GUATE, RIA DE :~F ,~l TZ'! B'Al TZ' ~ NAJSA' B'INCHB' B4TAB'AL NATAB'AL Sil l" \'jT'il YU' 'AM K'UULANi ~tri' B'ANIT M B'ANITAJIK T J'CHIL N Z JUTZE'CHIL " fl~'EB'ANI MACH XJALAN tJ '11 QAB'E! RI QAB'IIM TAJ R s~ ',4B'ElAl K'ULAL SNAB'ILAl· ~l GUATEMA MALA MEMORIA DE {~ At TZ'INIL NA TZ'INll NA'TAS'Al TZ' ii~,~ NAJSA'N TUJ QLO TUJ QLOLJ B'INCHB' ~ NATAB'AL 51LAN NATAB 51 B L SILAN NATAB'AL SIL <; NT'IL YU'AM K'UULANT'IL YU'AM ULANT'IL YU'AM K'UULAN-I · 10 GUATEMALA MEMORIA DEL 51LENCIO GUATEMALA MEMORIA DE GUATEMALA MEMORY OF SILENCE ·,I·.· . -

Guatemala 10

10 Guatemala Overview of the situation malaria in Guatemala has affected departments in the north of the country, in other words, El Figures 1-5 Peten, Alta Verapaz, Izabal and El Quiche. But, In Guatemala, 70% of the territory is considered in recent years, transmission in the Department endemic. Although the number of cases in the of Escuintla on the Pacific coast has garnered at- country has fallen considerably in the last decade, tention. This change can be attributed to, on the transmission continues in a significant number one hand, the impact of foreign assistance on the of municipalities in over 10 departments. Of northern region of the country, where new stra- countries in Central America, Guatemala was tegies, such as ITNs, breeding site control and second only to Honduras in the number of ca- diagnostic and treatment improvements, have ses in 2008. While the number of cases by Plas- been implemented. On the other hand, mosquito modium vivax was similar in the two countries, breeding sites have proliferated in the Escuint- Guatemala had very few P. falciparum cases. It la region, as has large-scale domestic migration had only 50 cases by this type of malaria parasite driven by sugarcane harvesting activities. Mala- in 2008, all of them autochthonous. ria is present primarily in the lowlands of these Malaria in the country is focalized in three departments. areas: 1) the Pacific region, particularly in the The vector species involved are Anopheles departments of Escuintla, Suchitepequez, San albimanus, A. darlingi, A. pseudopunctipennis Marcos and Quetzaltenango; 2) northeast of and A. -

Biodiversity and Conservation of Sierra Chinaja: a R Apid

Biodiversity AND Conservation of Sierra ChinajA: A r apid ASSESSMENT OF BIOPHYSICAL, SOCIOECONOMIC, AND MANAGEMENT FACTORS IN ALTAVERAPAZ, GUATEMALA by Quran A. Bonham B.S. Cornell University, 2001 presented in partial fuifiiiment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana August 2006 Approved by: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date Bonham, Curan A. M.S., August 2006 Forestry Biodiversity and Conservation of Sierra Chinaja: A rapid assessment of biophysical, socioeconomic, and management factors in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala Chairperson: Stephen Siebert The Sierra Chinaja is a low lying range of karst mountains in the heart of one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots, the Mesoamerican Forests. In 1989 these mountains were declared an area of special protection according to article 4-89 of Guatemalan law. Nevertheless, there is little management implementation on the ground and significant encroachment on important habitat and settlement of public lands by landless campesino farmers. The first step required by Guatemalan law to move the Sierra Chinaja from an area of special protection to a functional protected area is the preparation of a “technical study”. The goal of this document is to provide initial characterization of the biophysical, ecological, and socioeconomic features. It also identifies threats and suggests potential management strategies for the conservation of the Sierra Chinaja. Data were collected using biophysical and socioeconomic rapid assessment techniques from May 2005-Jan. 2006. This study represents the first systematic effort to characterize the biodiversity of Sierra Chinaja. The number of plant and animal species recorded included: 128 birds, 24 reptiles, 15 amphibians, 25 bats, 20 dung beetles, 72 trees, 63 orchids, and 198 plants total. -

BAJA VERAPAZ CHIMALTENANGO CHIQUIMULA Direcciones De Las

Direcciones de las Oficinas del Registro Nacional de las Personas Abril 15́ No. DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO REGISTRO AUXILIAR DIRECCION SEDE ALTA VERAPAZ 1 ALTA VERAPAZ COBAN 4a. avenida 4-50, Barrio Santo Domingo, zona 3 2 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA CRUZ VERAPAZ Calle 3 de Mayo, Zona 4 3 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN CRISTOBAL VERAPAZ 3a. Avenida 1-38 Zona 1, Barrio Santa Ana 4 ALTA VERAPAZ TACTIC 8 Avenida 4-72 Zona 1, Barrio La Asunción 5 ALTA VERAPAZ TAMAHU Barrio San Pablo, Tamahu 6 ALTA VERAPAZ TUCURU Barrio El Centro, Calle Principal, Avenida Tucurú 7 ALTA VERAPAZ PANZOS Barrio el Centro, Calle del Estadio a 150 Mts. De la Municipalidad 8 ALTA VERAPAZ SENAHU Calle Principal del Municipio de Senahú 9 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN PEDRO CARCHA 2a. Calle 12-58 zona 5, Barrio Chibujbu 10 ALTA VERAPAZ SAN JUAN CHAMELCO 2a. Ave. Barrio san Juan 11 ALTA VERAPAZ LANQUIN Cruce el Pajal Sebol Lanquin 12 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA MARIA CAHABON Barrio Santiago 89-97 zona 0, camino a Escuela Saquija 13 ALTA VERAPAZ CHISEC Barrio el Centro, Lote 241-1 14 ALTA VERAPAZ CHAHAL Barrio el Centro, a un costado del TSE 15 ALTA VERAPAZ FRAY BARTOLOME DE LAS CASAS F.T.N. 0-70 zona 1 16 ALTA VERAPAZ SANTA CATALINA LA TINTA Barrio Centro Zona 4 17 ALTA VERAPAZ RAXRUHA barrio concepcion lote 47, centro urbano poligono 1, camino a la Aldea la Isla BAJA VERAPAZ 1 BAJA VERAPAZ SALAMA 6a Avenida 5-71 Zona 1, salama 2 BAJA VERAPAZ SAN MIGUEL CHICAJ Cantón La Cruz 3 BAJA VERAPAZ RABINAL 3a. -

Cobertura Eléctrica De Guatemala

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ENERGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE DESARROLLO ENERGÉTICO UNIDAD DE PLANIFICACIÓN ENERGÉTICA 24 calle 21-12 zona 12, PBX: 2419 6363 Fax: 24762007 e-mail: [email protected] COBERTURA ELÉCTRICA DE GUATEMALA Fórmula: % Cobertura = Hogares electrificados / Hogares totales*100% Hogares Electrificados: Los hogares electrificados son todos los usuarios del servicio de energía eléctrica conectados a una red de distribución y los hogares que poseen iluminación por medio de paneles solares Para la obtención de los datos de los usuarios con servicio de energía eléctrica se requirió información a: EEGSA DEOCSA DEORSA Empresas Eléctricas municipales Ministerio de Energía y Minas Los datos de hogares con paneles solares de energía eléctrica se obtuvieron de información publicada por el INE en el Censo del 2002. Los datos sobre hogares conectados en zonas fronterizas se obtuvieron de las autorizaciones realizadas por el Ministerio de Energía y Minas para la asociación o consejos que están conectadas de esta forma. Las siguientes tablas muestran los datos de los hogares electrificados (usuarios) al 31 de diciembre de 2008. DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ENERGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE DESARROLLO ENERGÉTICO UNIDAD DE PLANIFICACIÓN ENERGÉTICA 24 calle 21-12 zona 12, PBX: 2419 6363 Fax: 24762007 e-mail: [email protected] HOGARES ELECTRIFICADOS A DICIEMBRE 2008 Usuarios Conectados Paneles Total Departamento Municipio Distribuidoras EM Fronterizos Solares electrificados ALTA VERAPAZ CAHABON 1581 855 2436 ALTA VERAPAZ CHAHAL 494 4 498 ALTA VERAPAZ -

Land & Sovereignty in the Americas

Land & Sovereignty T in the Americas N Issue Brief N°1 - 2013 I “Sons and daughters of the Earth”: Indigenous communities and land grabs in Guatemala By Alberto Alonso-Fradejas Copyright © 2013 by Food First / Institute for Food and Development Policy All rights reserved. Please obtain permission to copy. Food First / Institute for Food and Development Policy 398 60th Street, Oakland, CA 94618-1212 USA Tel (510) 654-4400 Fax (510) 654-4551 www.foodfirst.org [email protected] Transnational Institute (TNI) De Wittenstraat 25 1052 AK Amsterdam, Netherlands Tel (31) 20-6626608 Fax (31) 20-6757176 www.tni.org [email protected] Cover and text design by Zoe Brent Cover photo by Caracol Producciones Edited by Annie Shattuck, Eric Holt-Giménez and Tanya Kerssen About the author: Alberto Alonso-Fradejas ([email protected]) is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, Netherlands. This brief is adapted, with permission by the author, from: Alonso-Fradejas, Alberto. 2012. “Land control-grabbing in Guatemala: the political economy of contemporary agrarian change” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 33(4): 509-528. About the series: The Land & Sovereignty in the Americas series pulls together research and analysis from activists and scholars working to understand and halt the alarming trend in “land grabbing”—from rural Brazil and Central America to US cities like Oakland and Detroit— and to support rural and urban communities in their efforts to protect their lands as the basis for self-determination, food justice and food sovereignty. The series is a project of the Land & Sovereignty in the Americas (LSA) activist-researcher collective, coordinated by Food First. -

Coffee and Civil War the Cash Crop That Built the Foundations for the Mass Slaughter of Mayans During the Guatemalan Civil War

Coffee and Civil War The Cash Crop That Built the Foundations for the Mass Slaughter of Mayans during the Guatemalan Civil War By Mariana Calvo A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for honors Department of History, Duke University Under the advisement of Dr. Adriane Lentz-Smith April 19, 2017 Calvo 1 I can tell you these stories, telling it is the easy part, but living it was much harder. -Alejandro, 20151 1 Alejandro is one of the eight people whose testimony is featured in this thesis. Calvo 2 Abstract This thesis explores the connections between coffee production and genocide in Guatemala. This thesis centers its analysis in the 19th and 20th centuries when coffee was Guatemala’s main cash crop. Coffee became Guatemala’s main export after the Liberal Revolution of 1871. Prior to 1871, the ruling oligarchy in Guatemala had been of pure European descent, but the Liberal Revolution of 1871 gave power to the ladinos, people of mixed Mayan and European descent. With the rise of coffee as an export crop and with the rise of ladinos to power, indigenous Guatemalans from the western highlands were displaced from their lands and forced to labor on coffee plantations in the adjacent piedmont. Ladino elites used racism to justify the displacement and enslavement of the indigenous population, and these beliefs, along with the resentment created by the continued exploitation of indigenous land and labor culminated in the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996). This conflict resulted in the genocide of Maya communities. Historians have traced the war to the 1954 CIA backed coup that deposed democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz over fears that he was a Communist. -

Experiencias En El Programa De SAN En Comunidades Rurales De Rabinal

UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONOMICAS Y AMBIENTALES “EXPERIENCIAS EN EL PROGRAMA DE SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL EN COMUNIDADES RURALES DE RABINAL Y CUBULCO, DEPARTAMENTO DE BAJA VERAPAZ” GUATEMALA, SEPTIEMBRE 2009. UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONOMICAS Y AMBIENTALES EXPERIENCIAS EN EL PROGRAMA DE SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL EN COMUNIDADES RURALES DE RABINAL Y CUBULCO, DEPARTAMENTO DE BAJA VERAPAZ TESIS PRESENTADA A LA HONORABLE JUNTA DIRECTIVA DE LA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA POR MARIO BERNABE AREVALO JUCUB En el acto de investidura como INGENIERO AGRÓNOMO en SISTEMAS DE PRODUCCIÓN AGRÍCOLA EN EL GRADO ACADEMICO DE LICENCIADO Guatemala, Septiembre 2009. UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES AGRONOMICAS Y AMBIENTALES RECTOR Lic. Carlos Estuardo Gálvez Barrios JUNTA DIRECTIVA DE LA FACULTAD DE AGRONOMIA Decano MSc. Francisco Javier Vásquez Vásquez Vocal I Ing. Agr. Waldemar Nufio Reyes Vocal II Ing. Agr. Walter Arnoldo Reyes Sanabria Vocal III MSc. Danilo Ernesto Dardón Ávila Vocal IV P. For. Axel Esaú Cuma Vocal V Br. Carlos Alberto Monterroso Gonzales Secretario MSc. Edwin Enrique Cano Morales Guatemala, Septiembre 2009 Guatemala, Septiembre 2009. Honorable Junta Directiva. Honorable Tribunal Examinador. Facultad de Agronomía. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Presente. Distinguidos miembros: De conformidad con las normas establecidas en la Ley Orgánica de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, tengo el honor de someter a su consideración el trabajo de tesis del Programa Extraordinario, titulado: “EXPERIENCIAS EN EL PROGRAMA DE SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL EN COMUNIDADES RURALES DE RABINAL Y CUBULCO, DEPARTAMENTO DE BAJA VERAPAZ” Presentado como requisito previo para optar al Titulo de Ingeniero Agrónomo en Sistemas de Producción Agrícola, en el grado académico de Licenciado.