Download 1.16 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lo Fil) 2Ozo by and Between

* Contract ID 20Proo41 Contract Name Convergence and Specia! Support Program - Construction/ Improvement of Access Roads leading to Declared Tourism Destinations, Tadian-sagada Via Besao Road leading to Tirad Pass View, Fidelisan Falls, Sumaguing Cave, Balangagan Cave, Ayyuweng di lambak ed Tadian Festival, Kiltepan Sunrise, Besao Sunset Hanging Coffins, Echo Valley, Tadian, Mountain Province Location of the .Tadian, Mountain Province Contract CONTRACT AGREEMENT KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS: This CONTRACT AGREEMENT, made this lo fil) 2ozo by and between: The GOVERNMENT irr THE REPUBLTC OF THE PHILTPPTNES through the Department of Public Works and Highways-Mountain Province First District Engineering Office (DPWH-MPFDEO) represented herein by ALEXANDER C. CASTAfrEDA, District Engineer, duly authorized for this purpose, with main office address at Lower Caluttit, Bontoc, Mountain Province, hereinafter referred to as the "PROCURING ENTITY"; GENERAL CONSTRUCTION, a single proprietorship organized and existing and by virtue of laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with main office address at POBLACION, TADIAN, MOUNTAIN PROVINCE, represented herein by REYNALDO S. DEL AMOR, duly authorized for this purpose, hereinafter referred to as the *CONTRACTOR; WITNESSETH: WHEREAS, the PROCURING ENTITY is desirous that the CONTRACTOR execute the Works under 20PI0041 - Convergence and Special Support Program Construction/ Improvement of Access Roads leading to Declared Tourism Destinations, Tadian-Sagada via Besao Road leading to Tirad Pass View, 6 -

2278-6236 Inayan: the Tenet for Peace Among Igorots

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 INAYAN: THE TENET FOR PEACE AMONG IGOROTS Rhonda Vail G. Leyaley* Abstract: This research study was conducted to determine the meaning of Inayan and how this principle is used by the Igorots as a peaceful means of solving issues that involves untoward killings, accidents, theft and land grabbing. The descriptive method was used in this study. Key informants were interviewed using a prepared questionnaire. Foremost, the meaning of Inayan among Igorots is, it is the summary of the Ten Commandments. For more peaceful means, they’d rather do the rituals like the “Daw-es” to appease their pain and anger. This is letting the Supreme Being which they call Kabunyan take the course of action in “punishing” those who have committed wrong towards them. It is recommended that the principles of Inayan be disseminated to the younger generation through the curriculum; that the practices and rituals will be fully documented to be used as references; and to develop instructional materials that will advocate the principle of Inayan; Keywords: Inayan, Peace, Igorots, Rituals, Kankanaey *Bulanao, Tabuk City, Kalinga Vol. 5 | No. 2 | February 2016 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 239 International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 I. INTRODUCTION In a society where tribal conflicts are very evident, a group of individuals has a very distinguishable practice in maintaining the culture of peace among themselves. They are the Igorots. The Cordillera region of Northern Philippines is the ancestral domain of the Igorots. -

SOIL Ph MAP ( Key Rice Areas ) PROVINCE of KALINGA ° Province of Cagayan SCALE 1 : 75 , 000

121°0' 121°10' 121°20' 121°30' 121°40' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S Province of Apayao D E P A R T M E N T O F A G R I C U L T U R E 17°40' BUREAU OF SOILS AND 17°40' WATER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Road,cor.Visayas Ave.,Diliman,Quezon City SOIL pH MAP ( Key Rice Areas ) PROVINCE OF KALINGA ° Province of Cagayan SCALE 1 : 75 , 000 0 1 2 4 6 8 Kilometers Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : Luzon 1911 DISCLAIMER: All political boundaries are not authoritative Pinukpuk ! Province of Abra 17°30' Rizal ! 17°30' Balbalan ! TABUK \ Pasil ! Lubuagan ! Province of Isabela 17°20' 17°20' Tanudan LOCATION MAP ! 18° 20° Apayao Cagayan LEGEND LUZON Ilocos Sur 15° pH Value GENERAL AREA MAPPING UNIT DESCRIPTION 17°30' ( 1:1 RATIO ) RATING ha % Tinglayan KALINGA ! Nearly Neutral 454 2.25 > 6.8 or to Extremely Isabela Alkaline 1,771 8.76 Low VISAYAS 10° - < 4.5 Extremely Acid - Mt. Province - 17° Ifugao - Moderately Very Strongly MINDANAO 4.6 - 5.0 - 121° 121°30 ' 120° 125° Low Acid - Moderately 1 ,333 6.60 5.1 - 5.5 Strongly Acid High 3 ,159 15.63 Moderately 10,716 53.03 CONVENTIONAL SIGNS MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION 5.6 - 6.8 High Acid to Slightly SOURCES OF INFORMATION : Topographic information taken from NAMRIA Topographic Map at a scale of Acid 2,774 13.73 1:50,000.Elevation data taken from SRTM 1 arc-second global dataset (2015). -

Imperialist Campaign of Counter-Terrorism

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo English Edition Vol. LII No. 11 June 7, 2021 www.cpp.ph 9 NPA offensives in 9 days VARIOUS UNITS OF the New People's Army (NPA) mounted nine tactical offensives in the provinces of Davao Oriental, Quezon, Occidental Mindoro, Camarines Sur, Northern Samar at Samar within nine days. Six‐ teen enemy troopers were killed while 18 others were wounded. In Davao Oriental, the NPA ambushed a military vehicle traversing the road at Sitio Tagawisan, Badas, Mati City, in the morning of May 30. Wit‐ nesses reported that two ele‐ EDITORIAL ments of 66th IB aboard the vehicle were slain. The offensive was launched just a kilometer Resist the scheme away from a checkpoint of the PNP Task Force Mati. to perpetuate In Quezon, the NPA am‐ bushed troops of the 85th IB in Duterte's tyranny Barangay Batbat Sur, Buenavista on June 6. A soldier was killed odrigo Duterte's desperate cling to power is a manifestation of the in‐ and two others were wounded. soluble crisis of the ruling semicolonial and semifeudal system. It In Occidental Mindoro, the Rbreeds the worst form of reactionary rule and exposes its rotten core. NPA-Mindoro ambushed joint It further affirms the correctness of waging revolutionary struggle to end the operatives of the 203rd IBde and rule of the reactionary classes and establish people's democracy. police aboard a military vehicle at Sitio Banban, Nicolas, A few months prior to the 2022 ties and dictators. Magsaysay on May 28. The said national and local elections, the This maneuver is turning out to unit was on its way to a coun‐ ruling Duterte fascist clique is now be Duterte's main tactic to legalize terinsurgency program in an ad‐ busy paving the way to perpetuate his stay in power beyond the end of jacent barangay, along with its tyrannical rule. -

Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Subproject: Rehabilitation of Ga-Ang Footpath Ga-Ang, Tanudan, Kalinga

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 41220-013 August 2020 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Subproject: Rehabilitation of Ga-ang Footpath Ga-ang, Tanudan, Kalinga Prepared by the Municipality of Tanudan, Kalinga for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Asian Development Bank. i i This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 15 July 2020) The date of the currency equivalents must be within 2 months from the date on the cover. Currency unit – peso (PhP) PhP 1.00 = $ 0.02023 $1.00 = PhP 49.4144 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank BDC barangay development council BUB bottom-up budgeting CNC certificate of non-coverage COVID corona virus disease CSC construction supervision consultant CSO civil society organization DA Department of Agriculture DED detailed engineering design DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DSWD Department of Social Welfare and Development ECA environmentally critical area ECC environmental -

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

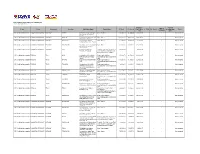

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

Municipal Government of Sadanga, Mountain Province

MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT OF SADANGA, MOUNTAIN PROVINCE CITIZEN’S CHARTER 2020 (1st Edition) I. MANDATE: Deriving its mandate from the Local Government Code of 1991, also known as RA 7160, the mission to follow the people’s welfare under Section 16 of the Code, to wit: General Welfare: Every LGU shall exercise the powers expressly granted, those necessarily implied therefrom, as well as powers, necessary, appropriate, or incidental for its efficient and effective governance and those which are essential to the promotion of the general welfare within their respective territorial jurisdictions. LGU shall ensure and support among other things, the preservation and enrichment of culture, promote health and safety, enhance the right of the people to a balance ecology, encourage and support the development of appropriate and self-reliant, scientific and technological capabilities, improve public morals, enhance economic prosperity and social justice, promote full employment among their residents, maintain peace and order, and preserve the comfort and convenience of the inhabitant. II. VISION: “ADAYSA NA SADANGA” Dream paradise in the Gran Cordillera that is adaptive, resilient and vibrant community with politically matured, culturally enriched, peace loving, spiritually, strengthened, healthy and child friendly people enjoying a robust economy in a safe and sustainable environment, led by committed and proactive leaders in a participatory and collective governance. III. MISSION: Lead the people to be at pace with the changing times by pursuing equitable socio-economic growth, optimizing resources, improving the quality and delivery of basic services and prudently putting in place relevant infrastructures and socio- economic activities yet keeping intact the locality’s natural endowments and ecological balance while promoting peace and enhancing our indigenous cultural heritage. -

Indigenous Peoples Plan PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project

Indigenous Peoples Plan Project number: 41220-013 April 2020 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Subproject: Rehabilitation of Ga-ang Footpath in Tanudan, Kalinga Prepared by the Municipality of Tanudan, Province of Kalinga for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 March 2020) Currency unit – peso (PhP) PhP1.00 = $0.01941 $1.00 = PhP 51.5175 ABBREVIATIONS ADB − Asian Development Bank ADSDPP − Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan BDC − Barangay Development Council BPMET − Barangay Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation Team CADT − Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title CAR − Cordillera Administrative Region CENRO − Community Environment and Natural Resources Office CoE − council of elders CP − certificate precondition DA − Department of Agriculture DENR − Department of Environment and Natural Resources GRC − grievance redress council GRM − grievance redress mechanism FPIC − free and prior informed consent INREMP − Integrated Natural Resources and Environment Management Project ICC − indigenous cultural communities IP − indigenous people IPP − indigenous peoples plan IPRA − indigenous peoples rights act LGU − Local Government Unit MDC − Municipal Development Council ME − municipal engineer MPDO − Municipal Planning and Development Office NCIP − National Commission on Indigenous Peoples O&M − operation and maintenance PENRO − Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office PPCO − Provincial Planning and Coordinating Officer PSO − Project Support Office ROW -

Gr 212564 2015.Pdf

' .. •' ~ l\epublit- of tbe l)lJtlipptnes &upreme teourt ;llanila TIDRD DIVISION NOTICE · Sirs/Mesdames: Please take notice that the Court, Third Division, issued a Resolution dated. March 18, 2015, which reads as follows: G.R. No. 212564 (People of the Philippines vs. Fermin Cawaren y Chakiwag alias "Aray'?. - This is an appeal from the Decision1 dated November 29, 2013 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CR-HC No. 05472 which affirmed with modification the Judgment2 dated January 26, 2012 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Bontoc, Mountain Province, Branch 35, in Criminal Case No. 2010-12-16-88. The RTC convicted Fermin Cawaren y Chakiwag alias "Aray" (Cawaren) of the crime of Murder and sentenced him to s4ffer reclusion perpetua without pronouncement as to civil damages which was amicably settled and paid to the heirs of Salvador T. Padya-os (Salvador), the victim. On December 16, 2010, an information was filed charging Cawaren with the crime of murder defined and penalized under Article 248 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC), the accusatory portion of which reads: That on or about December 14, 2010, in the afternoon thereof, at Sitio Fangek, Poblacion, Sadanga, Mountain Province, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, with intent to kill and with evident premeditation and by means of treachery, did then and there willfully, Unlawfully and feloniously attack, assault and x x .x with the use of a six[ ](6) inches blade knife stab SALVADOR T. PADYA-OS, thereby inflicting upon the latter, stab wound, .4th ICS PARAVERTEBRAL ARFP right and which caused the death of the aforenamed victim, all to the damage and prejudice of the aforementioned victim, all to the damage and prejudice of his heirs. -

NDCC Update Sitrep No. 19 Re TY Pepeng As of 10 Oct 12:00NN

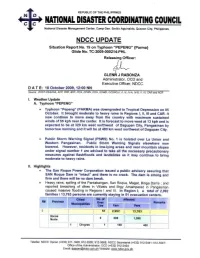

2 Pinili 1 139 695 Ilocos Sur 2 16 65 1 Marcos 2 16 65 La Union 35 1,902 9,164 1 Aringay 7 570 3,276 2 Bagullin 1 400 2,000 3 Bangar 3 226 1,249 4 Bauang 10 481 1,630 5 Caba 2 55 193 6 Luna 1 4 20 7 Pugo 3 49 212 8 Rosario 2 30 189 San 9 Fernand 2 10 43 o City San 10 1 14 48 Gabriel 11 San Juan 1 19 111 12 Sudipen 1 43 187 13 Tubao 1 1 6 Pangasinan 12 835 3,439 1 Asingan 5 114 458 2 Dagupan 1 96 356 3 Rosales 2 125 625 4 Tayug 4 500 2,000 • The figures above may continue to go up as reports are still coming from Regions I, II and III • There are now 299 reported casualties (Tab A) with the following breakdown: 184 Dead – 6 in Pangasinan, 1 in Ilocos Sur (drowned), 1 in Ilocos Norte (hypothermia), 34 in La Union, 133 in Benguet (landslide, suffocated secondary to encavement), 2 in Ifugao (landslide), 2 in Nueva Ecija, 1 in Quezon Province, and 4 in Camarines Sur 75 Injured - 1 in Kalinga, 73 in Benguet, and 1 in Ilocos Norte 40 Missing - 34 in Benguet, 1 in Ilocos Norte, and 5 in Pangasinan • A total of 20,263 houses were damaged with 1,794 totally and 18,469 partially damaged (Tab B) • There were reports of power outages/interruptions in Regions I, II, III and CAR. Government offices in Region I continue to be operational using generator sets. -

Issn: 2278-6236 the Indigenous Practices, Beliefs, And

International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences ISSN: 2278-6236 THE INDIGENOUS PRACTICES, BELIEFS, AND RITUALS OF THE UNOY RICE FARMERS OF KALINGA, NORTHERN PHILIPPINES - AN ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH Edgar M. Naganag* INTRODUCTION: The province of Kalinga is a land-lack province located at the central portion of the Cordillera Administrative Region, Philippines. It has eight municipalities divided into two political districts. The Municipality of Tanudan belongs to District 2. It is considered as a fifth class municipality located in the hinterland of the province inhabited by the indigenous peoples of Kalinga, the Itanudan. The municipality of Tanudan was then made up of only five barangays grouped according to ethno-linguistic clusters. These are Dacalan, Ga-ang, Lubo, Mangali, Taloctoc and Pangol. During the olden times, the people of Tanudan struggled for survival over harsh realities of their unexplored but kind environment. Though the lower portion of the municipality is accessible to land transportation it is just recent that the road was opened to Taloctoc and Mangali. The staple food of the people is rice. They produce the rice in their fields (pappayaw) or in the upland slash-and-burn (uma). The uma farming system has always been practiced by the people of Tanudan, but there is no proof of its real beginning. There are some ideas of how the Uma started in Tanudan, but these are purely hearsays for lack of corroborating evidence. *Kalinga-Apayao State College, Tabuk City, Philippines Vol. 2 | No. 12 | December 2013 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 331 International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences ISSN: 2278-6236 The stories of the old folks have dubious sources and each story teller has his or her version which at the end favors his own barangay or sub-tribe. -

Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy?

WORKING PAPER Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy? Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness RSN-PCC WORKING PAPER 15-010 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2640571 ASIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT RIZALINO S. NAVARRO POLICY CENTER FOR COMPETITIVENESS WORKING PAPER Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy? Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness AUGUST 2015 The authors would like to thank retired Associate Justice Adolfo Azcuna, Dr. Florangel Rosario-Braid, and Dr. Wilfrido Villacorta, former members of the 1986 Constitutional Commission; Dr. Bruno Wilhelm Speck, faculty member of the University of São Paolo; and Atty. Ray Paolo Santiago, executive director of the Ateneo Human Rights Center for the helpful comments on an earlier draft. This working paper is a discussion draft in progress that is posted to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Asian Institute of Management. Corresponding Authors: Ronald U. Mendoza, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. Fax: +632-465-2863. E-mail: [email protected] Jan Fredrick P. Cruz, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. Fax: +632-465-2863. E-mail: [email protected] RSN-PCC WORKING PAPER 15-010 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2640571 1. Introduction Political dynasties, simply defined, refer to elected officials with relatives in past or present elected positions in government.