Indigenous Peoples Plan PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Auction Will Take Place at 9 A.M. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 18Th October 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia

The Auction will take place at 9 a.m. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 18th October 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia. Viewing of lots will take place on Saturday 17th October 9am to 4pm & Sunday 18th October 7:00am to 8:45am, with the auction taking place at 9am and finishing around 5:00pm. Photos of each lot can be viewed via our ‘Auction’ tab of our website www.jbmilitaryantiques.com.au Onsite registration can take place before & during the auction. Bids will only be accepted from registered bidders. All telephone and absentee bids need to be received 3 days prior to the auction. Online registration is via www.invaluable.com. All prices are listed in Australian Dollars. The buyer’s premium onsite, telephone & absentee bidding is 18%, with internet bidding at 23%. All lots are guaranteed authentic and come with a 90-day inspection/return period. All lots are deemed ‘inspected’ for any faults or defects based on the full description and photographs provided both electronically and via the pre-sale viewing, with lots sold without warranty in this regard. We are proud to announce the full catalogue, with photographs now available for viewing and pre-auction bidding on invaluable.com (can be viewed through our website auction section), as well as offering traditional floor, absentee & phone bidding. Bidders agree to all the ‘Conditions of Sale’ contained at the back of this catalogue when registering to bid. Post Auction Items can be collected during the auction from the registration desk, with full payment and collection within 7 days of the end of the auction. -

2278-6236 Inayan: the Tenet for Peace Among Igorots

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 INAYAN: THE TENET FOR PEACE AMONG IGOROTS Rhonda Vail G. Leyaley* Abstract: This research study was conducted to determine the meaning of Inayan and how this principle is used by the Igorots as a peaceful means of solving issues that involves untoward killings, accidents, theft and land grabbing. The descriptive method was used in this study. Key informants were interviewed using a prepared questionnaire. Foremost, the meaning of Inayan among Igorots is, it is the summary of the Ten Commandments. For more peaceful means, they’d rather do the rituals like the “Daw-es” to appease their pain and anger. This is letting the Supreme Being which they call Kabunyan take the course of action in “punishing” those who have committed wrong towards them. It is recommended that the principles of Inayan be disseminated to the younger generation through the curriculum; that the practices and rituals will be fully documented to be used as references; and to develop instructional materials that will advocate the principle of Inayan; Keywords: Inayan, Peace, Igorots, Rituals, Kankanaey *Bulanao, Tabuk City, Kalinga Vol. 5 | No. 2 | February 2016 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 239 International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 I. INTRODUCTION In a society where tribal conflicts are very evident, a group of individuals has a very distinguishable practice in maintaining the culture of peace among themselves. They are the Igorots. The Cordillera region of Northern Philippines is the ancestral domain of the Igorots. -

Us M31 Rifle Grenade

1 DOUBLE STACK Manufactured NOW'S THE TIME!! ITALIAN JUST by Israel, these PISTOL MAG LOADER parts sets were BE THE FIRST GOTHIC IN!! stripped down TO KNOW ABOUT FOR 9MM & 40 S&W from Israeli OUR DEALS !!! Rugged synthetic Military Service ARMOR Join Our EMAIL BLAST List loader with an rifles and are in JUST Beautifully con- Today By Texting SARCO to ergonomic feel is very good shape structed Medieval 22828 And Receive A SPE- comfortable to use IN!! and contain all set of Italian Gothic CIAL DISCOUNT ! By doing so, and saves your parts for the Armor in steel that you’ll get our latest email blast finger tips and gun except for patience! The comes with Sword, offers, sale items and notifi- the barrel and cations of new goodies com- Loader is perfect Wood Base, and Ar- receiver. The set for the double ing in! AND… after you sign mature to hold the comes with a stack magazines up, receive a FREE deck of set in place. Overall Sling and Metric that load with 9mm authentic Cold War, Unissued & & 40 S&W ammo. height on stand is 20 rd. magazine Illustrated AIRCRAFT CARDS! Black color, New over 6.5 feet high. where permitted by law. Perfect kit for building your shooting FAL with one of the semi Just add them to your cart List price is $12.95 Extremely auto receivers and barrels offered elsewhere. Kit is sold without flash hider. using part number MISC168 SARCO SPECIAL limited ............................................................................................................... $425.00 FAL320 and enter source code EMAIL- ............... $7.95 each .........$1,200.00 Add a flash hider for an extra .............................................................................. -

"Bontoc" Is Derived from Two Morphemes "Bun" (Heap)

bontoc by Christina Sianghio "Bontoc" is derived from two morphemes "bun" (heap) and "tuk" (top), whi ch taken together, means "mountains." The term "Bontoc" now refers to the people of the Mountain Province used to consist of five subprovinces created during th e Spanich period: Benguet, Ifugao, Bontoc, Apayao and Kalinga. In 1966, four new provinces were created out of the original Mountain Province: Benguet, Ifugao, Mounatin Province (formerly the subprovince of Bontoc), and Kalinga-Apayao. Henc e, people may still erroneously refer to the four provinces as the Mountain Prov ince .The Mountain province sits on the Cordillera mountain range, which runs from no rth to south. It is bounded on the west by Ilocos Sur province, on the east by I sabela and Ifugao provinces, on the north by Kalinga-Apayao Province, and on the south by Ifugao and Beguet Provinces. Part of its western territory has been ca rved out to the jurisdiction of Ilocos Sur, and is drained by the Chico River. I ts capital is Bontoc town, which was also the capital of the former Mountain Pro vince. It has a total of 10 municipalities and 137 barrios. The villages at the southern end of the Mountain Province are northern Kankanay. Although there is a common language, also called Bontoc, each village may have its own dialect and phonetic peculiarities (NCCP-PACT). Pouplation estimate in 1988 was 148,000. Phy sical types are characteristically Philippine, with ancient Ainu and short Mongo l types. Religious Beliefs and Practices Although the Bontoc believe in the anito or spirits of their ancestors and in sp irits dwelling in nature, they are essentially monotheistic. -

SOIL Ph MAP ( Key Rice Areas ) PROVINCE of KALINGA ° Province of Cagayan SCALE 1 : 75 , 000

121°0' 121°10' 121°20' 121°30' 121°40' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S Province of Apayao D E P A R T M E N T O F A G R I C U L T U R E 17°40' BUREAU OF SOILS AND 17°40' WATER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Road,cor.Visayas Ave.,Diliman,Quezon City SOIL pH MAP ( Key Rice Areas ) PROVINCE OF KALINGA ° Province of Cagayan SCALE 1 : 75 , 000 0 1 2 4 6 8 Kilometers Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : Luzon 1911 DISCLAIMER: All political boundaries are not authoritative Pinukpuk ! Province of Abra 17°30' Rizal ! 17°30' Balbalan ! TABUK \ Pasil ! Lubuagan ! Province of Isabela 17°20' 17°20' Tanudan LOCATION MAP ! 18° 20° Apayao Cagayan LEGEND LUZON Ilocos Sur 15° pH Value GENERAL AREA MAPPING UNIT DESCRIPTION 17°30' ( 1:1 RATIO ) RATING ha % Tinglayan KALINGA ! Nearly Neutral 454 2.25 > 6.8 or to Extremely Isabela Alkaline 1,771 8.76 Low VISAYAS 10° - < 4.5 Extremely Acid - Mt. Province - 17° Ifugao - Moderately Very Strongly MINDANAO 4.6 - 5.0 - 121° 121°30 ' 120° 125° Low Acid - Moderately 1 ,333 6.60 5.1 - 5.5 Strongly Acid High 3 ,159 15.63 Moderately 10,716 53.03 CONVENTIONAL SIGNS MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION 5.6 - 6.8 High Acid to Slightly SOURCES OF INFORMATION : Topographic information taken from NAMRIA Topographic Map at a scale of Acid 2,774 13.73 1:50,000.Elevation data taken from SRTM 1 arc-second global dataset (2015). -

Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Subproject: Rehabilitation of Ga-Ang Footpath Ga-Ang, Tanudan, Kalinga

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 41220-013 August 2020 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Subproject: Rehabilitation of Ga-ang Footpath Ga-ang, Tanudan, Kalinga Prepared by the Municipality of Tanudan, Kalinga for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Asian Development Bank. i i This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 15 July 2020) The date of the currency equivalents must be within 2 months from the date on the cover. Currency unit – peso (PhP) PhP 1.00 = $ 0.02023 $1.00 = PhP 49.4144 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank BDC barangay development council BUB bottom-up budgeting CNC certificate of non-coverage COVID corona virus disease CSC construction supervision consultant CSO civil society organization DA Department of Agriculture DED detailed engineering design DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DSWD Department of Social Welfare and Development ECA environmentally critical area ECC environmental -

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

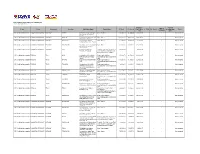

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

OKCA 32Nd Annual • April 14-15

OKCA 32nd Annual • April 14-15 KNIFE SHOW Lane Events Center & Fairgrounds • Eugene, Oregon April 2007 Ourinternational membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” You Could Win... a new Brand Name knife or other valuable prize, just for filling out a door prize coupon. Do it now so you don't forget! You can also... buy tickets in our Saturday (only) RAFFLE for chances to WIN even more fabulous knife prizes. Stop at the OKCA table before 5:00 p.m. Saturday. Tickets are only $1 each, or 6 for $5. Join in the Silent Auction... Saturday only we will have a display case filled with very special knives for bidding. Put in your bid and see if you will take home a very special prize. Free Identification & Appraisal Ask for Bernard Levine, author of Levine's Guide to Knives and Their Values, at table N-01. ELCOME to the Oregon Knife have Blade Forging, sword demonstrations, the raffle. See the display case by the exit to Collectors Association Special Show Scrimshaw, Engraving, Knife Sharpening, purchase tickets and see the items that you could WKnewslettter. On Saturday, April 14 Blade Grinding Competition, Wood Carving, win. and Sunday, April 15, we want to welcome you Balisong and Flint Knapping. And don't miss Along the side walls, we will have more than a and your friends and family to the famous and the FREE knife identification and appraisal by score of MUSEUM QUALITY KNIFE AND spectacular OREGON KNIFE SHOW & SALE. knife author BERNARD LEVINE SWORD COLLECTIONS ON DISPLAY for Now the Largest Knife Show in the World! (Table N-01). -

Indigenous Peoples Plan PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project

Indigenous Peoples Plan Project number: 41220-013 April 2020 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Subproject: Rehabilitation of Ga-ang Footpath in Tanudan, Kalinga Prepared by the Municipality of Tanudan, Province of Kalinga for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 March 2020) Currency unit – peso (PhP) PhP1.00 = $0.01941 $1.00 = PhP 51.5175 ABBREVIATIONS ADB − Asian Development Bank ADSDPP − Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan BDC − Barangay Development Council BPMET − Barangay Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation Team CADT − Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title CAR − Cordillera Administrative Region CENRO − Community Environment and Natural Resources Office CoE − council of elders CP − certificate precondition DA − Department of Agriculture DENR − Department of Environment and Natural Resources GRC − grievance redress council GRM − grievance redress mechanism FPIC − free and prior informed consent INREMP − Integrated Natural Resources and Environment Management Project ICC − indigenous cultural communities IP − indigenous people IPP − indigenous peoples plan IPRA − indigenous peoples rights act LGU − Local Government Unit MDC − Municipal Development Council ME − municipal engineer MPDO − Municipal Planning and Development Office NCIP − National Commission on Indigenous Peoples O&M − operation and maintenance PENRO − Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office PPCO − Provincial Planning and Coordinating Officer PSO − Project Support Office ROW -

A Dictionary of Kashmiri Proverbs & Sayings

^>\--\>\-«s-«^>yss3ss-s«>ss \sl \ I'!- /^ I \ \ "I I \ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library PN 6409.K2K73 A dictionary of Kashmiri proverbs & sayi 3 1924 023 043 809 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023043809 — : DICTIONARY KASHMIRI PROVERBS & SAYINGS Explained and Illustrated from the rich and interesting Folklore of the Valley. Rev. J. HINTON KNOWLES, F.R.G.S., M.R.A.S., &c., (C. M. S.) MISSIONARY TO THE KASHMIRIS. A wise man will endeavour " to understand a proverb and the interpretation." Prov. I. vv. 5, 6. BOMBAY Education Society's Press. CALCUTTA :—Thackbb, Spink & Co. LONDON :—Tetjenee & Co. 1885. \_All rights reserved.'] PREFACE. That moment when an author dots the last period to his manuscript, and then rises up from the study-chair to shake its many and bulky pages together is almost as exciting an occasion as -when he takes a quire or so of foolscap and sits down to write the first line of it. Many and mingled feelings pervade his mind, and hope and fear vie with one another and alternately overcome one another, until at length the author finds some slight relief for his feelings and a kind of excuse for his book, by writing a preface, in which he states briefly the nature and character of the work, and begs the pardon of the reader for his presumption in undertaking it. A winter in Kashmir must be experienced to be realised. -

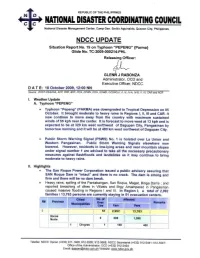

NDCC Update Sitrep No. 19 Re TY Pepeng As of 10 Oct 12:00NN

2 Pinili 1 139 695 Ilocos Sur 2 16 65 1 Marcos 2 16 65 La Union 35 1,902 9,164 1 Aringay 7 570 3,276 2 Bagullin 1 400 2,000 3 Bangar 3 226 1,249 4 Bauang 10 481 1,630 5 Caba 2 55 193 6 Luna 1 4 20 7 Pugo 3 49 212 8 Rosario 2 30 189 San 9 Fernand 2 10 43 o City San 10 1 14 48 Gabriel 11 San Juan 1 19 111 12 Sudipen 1 43 187 13 Tubao 1 1 6 Pangasinan 12 835 3,439 1 Asingan 5 114 458 2 Dagupan 1 96 356 3 Rosales 2 125 625 4 Tayug 4 500 2,000 • The figures above may continue to go up as reports are still coming from Regions I, II and III • There are now 299 reported casualties (Tab A) with the following breakdown: 184 Dead – 6 in Pangasinan, 1 in Ilocos Sur (drowned), 1 in Ilocos Norte (hypothermia), 34 in La Union, 133 in Benguet (landslide, suffocated secondary to encavement), 2 in Ifugao (landslide), 2 in Nueva Ecija, 1 in Quezon Province, and 4 in Camarines Sur 75 Injured - 1 in Kalinga, 73 in Benguet, and 1 in Ilocos Norte 40 Missing - 34 in Benguet, 1 in Ilocos Norte, and 5 in Pangasinan • A total of 20,263 houses were damaged with 1,794 totally and 18,469 partially damaged (Tab B) • There were reports of power outages/interruptions in Regions I, II, III and CAR. Government offices in Region I continue to be operational using generator sets. -

Issn: 2278-6236 the Indigenous Practices, Beliefs, And

International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences ISSN: 2278-6236 THE INDIGENOUS PRACTICES, BELIEFS, AND RITUALS OF THE UNOY RICE FARMERS OF KALINGA, NORTHERN PHILIPPINES - AN ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH Edgar M. Naganag* INTRODUCTION: The province of Kalinga is a land-lack province located at the central portion of the Cordillera Administrative Region, Philippines. It has eight municipalities divided into two political districts. The Municipality of Tanudan belongs to District 2. It is considered as a fifth class municipality located in the hinterland of the province inhabited by the indigenous peoples of Kalinga, the Itanudan. The municipality of Tanudan was then made up of only five barangays grouped according to ethno-linguistic clusters. These are Dacalan, Ga-ang, Lubo, Mangali, Taloctoc and Pangol. During the olden times, the people of Tanudan struggled for survival over harsh realities of their unexplored but kind environment. Though the lower portion of the municipality is accessible to land transportation it is just recent that the road was opened to Taloctoc and Mangali. The staple food of the people is rice. They produce the rice in their fields (pappayaw) or in the upland slash-and-burn (uma). The uma farming system has always been practiced by the people of Tanudan, but there is no proof of its real beginning. There are some ideas of how the Uma started in Tanudan, but these are purely hearsays for lack of corroborating evidence. *Kalinga-Apayao State College, Tabuk City, Philippines Vol. 2 | No. 12 | December 2013 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 331 International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences ISSN: 2278-6236 The stories of the old folks have dubious sources and each story teller has his or her version which at the end favors his own barangay or sub-tribe.