MAGIC and IDENTITY in OLDER SCOTS ROMANCE by RUTH HELEN CADDICK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing)

Programme MONDAY 30 JUNE 10.00-11.00 Plenary: Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing) 11.00-11.30 Coffee 11.30-1.00 Session 1 A) Narrating the Nation: Historiography and Identity in Stewart Scotland (c.1440- 1540): a) „Dream and Vision in the Scotichronicon‟, Kylie Murray, Lincoln College, Oxford. b) „Imagined Histories: Memory and Nation in Hary‟s Wallace‟, Kate Ash, University of Manchester. c) „The Politics of Translation in Bellenden‟s Chronicle of Scotland‟, Ryoko Harikae, St Hilda‟s College, Oxford. B) Script to Print: a) „George Buchanan‟s De jure regni apud Scotos: from Script to Print…‟, Carine Ferradou, University of Aix-en-Provence. b) „To expone strange histories and termis wild‟: the glossing of Douglas‟s Eneados in manuscript and print‟, Jane Griffiths, University of Bristol. c) „Poetry of Alexander Craig of Rosecraig‟, Michael Spiller, University of Aberdeen. 1.00-2.00 Lunch 2.00-3.30 Session 2 A) Gavin Douglas: a) „„Throw owt the ile yclepit Albyon‟ and beyond: tradition and rewriting Gavin Douglas‟, Valentina Bricchi, b) „„The wild fury of Turnus, now lyis slayn‟: Chivalry and Alienation in Gavin Douglas‟ Eneados‟, Anna Caughey, Christ Church College, Oxford. c) „Rereading the „cleaned‟ „Aeneid‟: Gavin Douglas‟ „dirty‟ „Eneados‟, Tom Rutledge, University of East Anglia. B) National Borders: a) „Shades of the East: “Orientalism” and/as Religious Regional “Nationalism” in The Buke of the Howlat and The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy‟, Iain Macleod Higgins, University of Victoria . b) „The „theivis of Liddisdaill‟ and the patriotic hero: contrasting perceptions of the „wickit‟ Borderers in late medieval poetry and ballads‟, Anna Groundwater, University of Edinburgh 1 c) „The Literary Contexts of „Scotish Field‟, Thorlac Turville-Petre, University of Nottingham. -

1427 to 1453

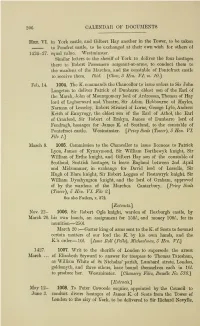

206 CALENDAE OF DOCUMENTS Hen. VI. in York castle, and Gilbert Hay another in the Tower, to be taken to Pomfret castle, to be exchanged at their own wish for others of 1426-27. equal value. Westminster. Similar letters to the sheriff of York to deliver the four hostages there to Eobert Passemere sergeant-at-arms, to conduct them to the wardens of the Marches, and the constable of Pontefract castle to receive them. IMd. {^Closc, 5 Hen. VI. m. JO.] Feb. 14. 1004. The K. commands the Chancellor to issue orders to Sir John Langeton to deliver Patrick of Dunbarre eldest son of the Earl of the March, John of Mountgomery lord of Ardrossan, Thomas of Hay lord of Loghorward and Yhestre, Sir Adam Hebbourne of Hayles, Norman of Lesseley, Eobert Stiward of Lome, George Lyle, Andrew Keith of Ennyrugy, the eldest son of the Earl of Athol, the Earl of Crauford, Sir Eobert of Erskyn, James of Dunbarre lord of Fendragh, hostages for James K. of Scotland, to the constable of Pontefract castle. Westminster. {^Privy Seals (Toiuer), 5 Hen. VI. File I] March 8. 1005. Commission to the Chancellor to issue licences to Patrick Lyon, James of Kynnymond, Sir William Borthewyk knight, Sir William of Erthe knight, and Gilbert Hay son of the constable of Scotland, Scottish hostages, to leave England between 2nd April and Midsummer, in exchange for David lord of Lesselle, Sir Hugh of Blare knight. Sir Eobert Loggan of Eestawryk knight, Sir William Dysshyngton knight, and the lord of Graham, approved of by the wardens of the Marches. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 12 2007 Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth- Century Scottish Literature Sally Mapstone St. Hilda's College, Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mapstone, Sally (2007) "Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 131–155. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sally Mapstone Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature Among the voluminous papers of William Drummond of Hawthomden, not, however with the majority of them in the National Library of Scotland, but in a manuscript identified about thirty years ago and presently in Dundee Uni versity Library, 1 is a small and succinct record kept by the author of significant events and moments in his life; it is entitled "MEMORIALLS." One aspect of this record puzzled Drummond's bibliographer and editor, R. H. MacDonald. This was Drummond's idiosyncratic use of the term "fatall." Drummond first employs this in the "Memorialls" to describe something that happened when he was twenty-five: "Tusday the 21 of Agust [sic] 1610 about Noone by the Death of my father began to be fatall to mee the 25 of my age" (Poems, p. -

First Series, 1883-1910 1 the Kingis Quair, Ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The

First Series, 1883-1910 1 The Kingis Quair, ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The Poems of William Dunbar I, ed. John Small 1893 3 The Court of Venus, by John Rolland. 1575, ed. Walter Gregor 1884 4 The Poems of William Dunbar II, ed. John Small 1893 5 Leslie’s Historie of Scotland I, ed. E.G. Cody 1888 6 Schir William Wallace I, ed. James Moir 1889 7 Schir William Wallace II, ed. James Moir 1889 8 Sir Tristrem, ed. G.P. McNeill 1886 9 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie I, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 10 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie II, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 11 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie III, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 12 The Richt Vay to the Kingdome of Heuine by John Gau, ed. A.F. Mitchell 1888 13 Legends of the Saints I, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1887 14 Leslie’s History of Scotland II, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 15 Niniane Winzet’s Works I, ed. J. King Hewison 1888 16 The Poems of William Dunbar III, ed. John Small, Introduction by Æ.J.G. Mackay 1893 17 Schir William Wallace III, ed. James Moir 1889 18 Legends of the Saints II, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1888 19 Leslie’s History of Scotland III, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 20 Satirical Poems of the Time of the Reformation I, ed. James Cranstoun REPRINT 1889 21 The Poems of William Dunbar IV, ed. John Small 1893 22 Niniane Winzet’s Works II, ed. J. King Hewison 1890 23 Legends of the Saints III, ed. -

Makar's Court

Culture and Sport Committee 2.00pm, Monday, 20 March 2017 Makars’ Court: Proposed Additional Inscriptions Item number Report number Executive/routine Wards All Executive Summary Makars’ Court at the Writers’ Museum celebrates the achievements of Scottish writers. This ongoing project to create a Scottish equivalent of Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey was the initiative of the former Culture and Leisure Department, in association with the Saltire Society and Lothian and Edinburgh Enterprise Ltd, as it was then known. It was always the intention that Makars’ Court would grow and develop into a Scottish national literary monument as more writers were commemorated. At its meeting on 10 March 1997 the then Recreation Committee established that the method of selecting writers for commemoration would involve the Writers’ Museum forwarding sponsorship requests for commemorating writers to the Saltire Society, who would in turn make a recommendation to the Council. The Council of the Saltire Society now recommends that two further applications be approved, to commemorate William Soutar (1898-1943) – poet and diarist, and George Campbell Hay (1915-1984) – poet. Links Coalition Pledges P31 Council Priorities CP6 Single Outcome Agreement SO2 Report Makar’s Court: Proposed Additional Inscriptions 1. Recommendations 1.1 It is recommended that the Committee approves the addition of the proposed new inscriptions to Makars’ Court. 2. Background 2.1 Makars’ Court at the Writers’ Museum celebrates the achievements of Scottish writers. This ongoing project to create a Scottish equivalent of Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey was the initiative of the former Culture and Leisure Department, in association with the Saltire Society and Lothian and Edinburgh Enterprise Ltd, as it was then known. -

114638654.23.Pdf

SCS ST£S!.lf-lj- ZTbe Scottish ZTcyt Society GILBERT OF THE HAYE’S PROSE MANUSCRIPT I. THE BUKE OF THE LAW OF ARMYS V" GILBERT OF THE HAYE’S PROSE MANUSCRIPT (A.D. 1456) VOLUME I. THE BUKE OF THE LAW OF ARMYS OR BUKE OF BATAILLIS EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION BY J. H. STEVENSON for tlje Societg bg WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON 1901 All Rights reserved PREFATORY NOTE. To the courtesy of the Honourable Mrs Maxwell-Scott of Abbotsford, in the first place, the Scottish Text Society is indebted for permission to print the Haye Prose Manuscript. The Dean and Council of the Faculty of Advocates, as trustees of the older Abbotsford Library, of which the volume forms a part, readily added their consent. The making of the transcript for the use of the printer was intrusted to the Rev. Walter MacLeod, but as the editor has carefully collated the transcript with both the print and the MS., he desires to take his full share of the responsibility of any mistakes which may still have crept into the print. J. H. S. CONTENTS OF THE FIRST VOLUME. INTRODUCTION— page 1. DESCRIPTION OF THE MANUSCRIPT . vii 2. THE TRANSLATOR ..... Xxiii 3. THE FORTUNES OF THE MANUSCRIPT . XXXvi 4. THE PLACE OF HAYE’S MS. IN EARLY SCOTTISH PROSE ...... lii 5. THE PRINCIPLES OF THE EDITING . lix HONORS BONET AND HIS ‘ ARBRE DES BATAILLES ’ . Ixiv THE BUKE OF THE LAW OF ARMYS— INTITULACIOUN ..... I RUBRICS OF FIRST PART .... I translator’s INTRODUCTION ... 2 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE ..... 2 FIRST PART OF THE BOOK ... -

Hates O F Tweeddale

GENEALOGIE OF THE HATES OF TWEEDDALE, FATHER RICHARD AUGUSTIN HAY, PRIOR OF ST. PIEREMONT, INCLUDING MEMOIRS OF HIS OWN TIMES. IMPRESSION. ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHT COPIES ON SMALL PAPER. TWELVE COPIES ON LARGE THICK PAPER. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTORYNOTICE. Page i 11. GENEALOGIEOF THE HAYESOF TWEEDDALE, - - '1 111. FATHERHAY'S MEDIOIRS OF HIS (?WN TIMES, - - 48 IV. 'APPENDIX. 2. Ane Epitome or Abridgement of what past at the L(ord) B[aImerino] his Arraignment CriminaJl before the Jus- tice, when he was put to the ~r&lof me Assyse, 86 3. Ceremonial of Burning the Pope, 30th November 1689, 102 4. Account of John Chieely of Dalry, - - - 106 5. An Account of the Misfortunes of Mrs. Erskine of Grange, commonly known as Lady Grange, - - - 112 6. Elegy on the never enough to be lamented Death of the Right Honourable Lord John Hay, Marquis of Twed- del, who departed this life the ?]st May 1713, - 126 HE Genealogie of the Farniiy of Haye of Tweeddale was compiled by Richard Augns- tin Hay, Canon Regular (as he designed himself) of c6 St. Genovefs of Paris," and " Prior of St. Pieremoat," and occurs in one of the volumes of his MS. collections belong- ing to the Faculty of Advocates. Being himself a descendant of that fanlily, and in direct succession to a part of the honours, his Memoir, in the latter portion of it, is;from its minuteness, of considerable importance. Its interest does not so much arise from the genealogical researches of the author, as from the histo- rical details which he has preserved of Scottish affairs from the period of the Restoration to the Revolution, which are extremely curious, and, on that account, well worthy of publication. -

William Dunbar: an Analysis of His Poetic Development

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 7-30-1976 William Dunbar: An Analysis of His Poetic Development G. David Beebe Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Beebe, G. David, "William Dunbar: An Analysis of His Poetic Development" (1976). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2385. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2382 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF G. David Beebe for the Master of Arts in English presented July 30, 1976. Title: William Dunbar: An Analysis of His Poetic Development. APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Ross Garner Theodore Grams This thesis examines the work of William Dunbar, a sixteenth century Scottish poet, in order to demonstrate that he is not, as he is often styled, a Scottish Chaucerian. It makes an analysis of the chronological occurrence of forms and themes in his poetry which indicates that his work can be divided into three periods: (1) an initial period in which his work deals with traditional matter and forms; (2) a second period in which he develops a distinctly personal poetic voice; and (3) a final period in which he perfects this personal voice and then relinquishes it for a public, religious one. -

The Historicity of Barbour's Bruce

The Historicity of Barbour's Bruce By JAMES HAND TAGGART School of Scottish Studies Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow A thesis submitted'to the University of Glasgow in May 2004 for the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy ii Acknowledgments Professor Geoffrey Barrow took time to discuss various aspects of Barbour's purpose in writing The Bruce. Professor Archie Duncan spent hours with me on several occasions. His knowledge of The Bruce is unsurpassed;he shared it most generously. He was patient when I questioned some of his conclusions about Barbour's work and its historicity. His edition of The Bruce, together with its extensivenotes, was invaluable for my analysis of Barbour. Drs. Sonia Cameron and Fiona Watson also gave generouslyof their time at crucial points. I am especially grateful to my supervisor, Professor Edward Cowan. He never failed to smile and brew up a coffee on the many occasionsI visited his room in the Department of Scottish History. He kept my enthusiasm going over a prolonged period, and helped to structure my work in a way that made the analyses more accessibleand the discussion more meaningful. He vigorously defendedme and my work against aggressive and unprofessional attack, and encouraged me to think rigorously at every point. I am glad, though, to observethat I finally convinced him that the carl of Carrick killed, but did not murder, the lord of Badenoch on 10 February 1306. Thanks for your guidanceand friendship, Ted. On a personal note, I am grateful to Fiona for starting me out on this journey, and to Mairi for sustaining me on the last few laps. -

BY Ph. D. UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH 1980

THE BRUCE: A STUDY OF JOHN BARBOUR'S HEROIC IDEAL BY ANNE M. MCKIM Ph. D. UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......... 000.0a ii INTRODUCTION .... 99oo*0@@0&a001 Chapter 1. FORM AND THEME ............. 28 2. THE THEOLOGICAL PHILOSOPHICALFRAMEWORK 67 AND ...... 3. JAMES DOUGLAS: THE IDEAL KNIGHT .... 0....... 122 4. ROBERTBRUCE: PORTRAIT OF-AN IDEAL KING ........ 176 5. LITERARY DEBTS AND INFLUENCES .... a. 0...... 233 CONCLUSION.......................... 288 a00aaa00000a0900a0000000000aa00000 SELECTEDBIBLIOGRAPHY 297 .................... ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to Patricia Crangle and to my husband Ian for kindly undertaking to proof-read this thesis and for offering helpful comments. I also wish to thank Professor John MacQueen of the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh, who supervised the writing of the thesis and offered invaluable advice and encouragement. ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to examine John Barbour's Bruce (c. 1375) as a literary work from the point of view of the author's heroic ideal. There has been singular confusion about the nature and form of the work and about Barbour's theme. Until recently, critics who have attempted to characterize and categorize the poem have concluded that although it shares some of the qualities and conventions of romance, epic, biography and verse-chronicle, it is a mixture of forms and is unusual because of Barbour's realistic treatment and patriotic emphasis. Various assumptions about medieval na tives have been brought to bear in these judgements and, on the whole, The Bruce has been found wanting or has been regarded as a modification of conventions especially with respect to chivalric codes of conduct and courtly ideals. -

Vernacular Literary Culture in Lowland Scotland, 1680-1750

Vernacular Literary Culture in Lowland Scotland, 1680-1750. George M. Brunsden. Submitted to the Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow, For the Degree of Ph.D. October, 1998. Research conducted in conjunction with the Department of Scottish History, University of Glasgow. © George M. Brunsden, 1998. ProQuest Number: 13818609 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818609 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY jJPDLPV i'34ol |rofa ' Abstract Vernacular Literary Culture in Lowland Scotland, 1680-1750. This thesis examines literature that because of the frequency of its printing, and social relevance, might be called prevalent examples of a tradition. The strength of these traditions over time, and the way in which they reflect values of Lowland Scottish society are also examined. Vernacular literary tradition faced a period of crisis during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and its survival seemed uncertain. Its vitality, however, was reaffirmed mainly because it was able to evolve. The actions of several key individuals were instrumental in its maintenance, but ultimately, it was the strength of the traditions themselves which proved to be most influential.